By Daniele Vianello

Claudio Longhi has been appointed Director of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano. Thus opens a third phase for the famous theatre, after months punctuated by exhausting controversies and political clashes between the Municipality and the Ministry on the one hand and the Lombardy Region on the other. At the same time, steps were taken to find a successor of Longhi as the director of the numerous theatres of the ERT Foundation – Emilia Romagna Teatro, which he led for four years, beginning in January 2017.

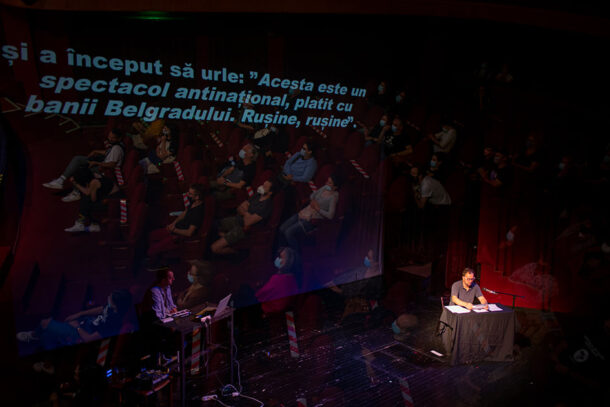

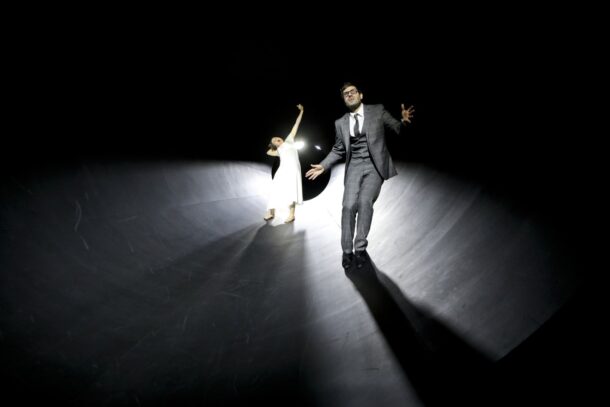

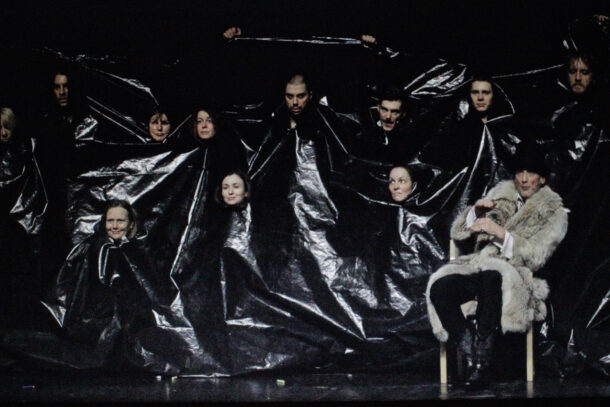

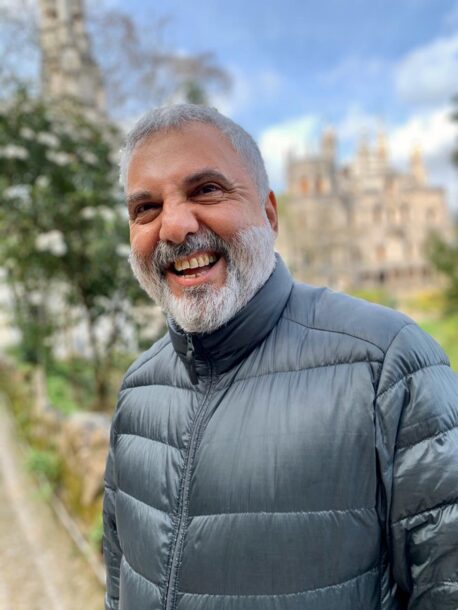

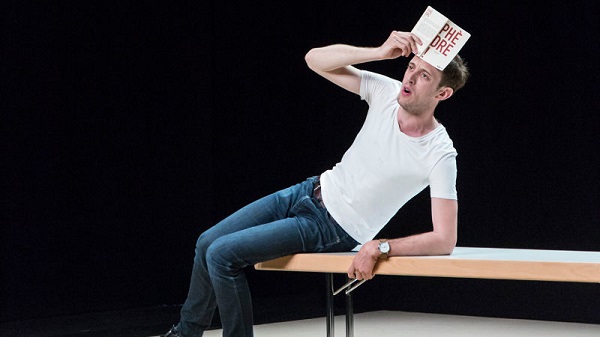

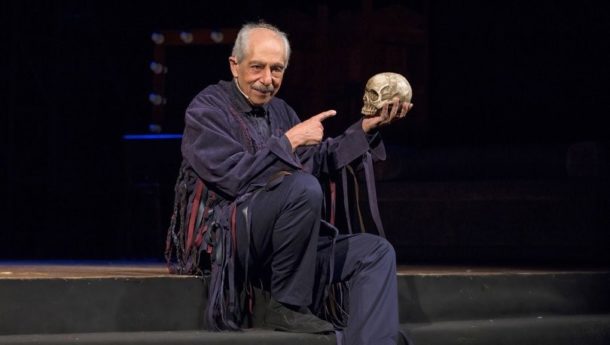

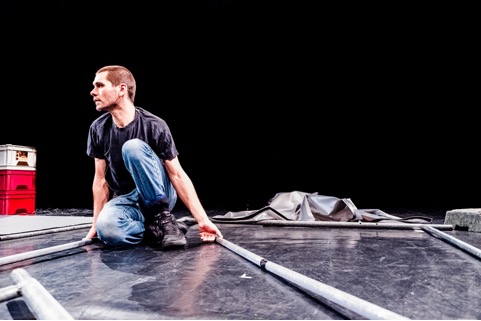

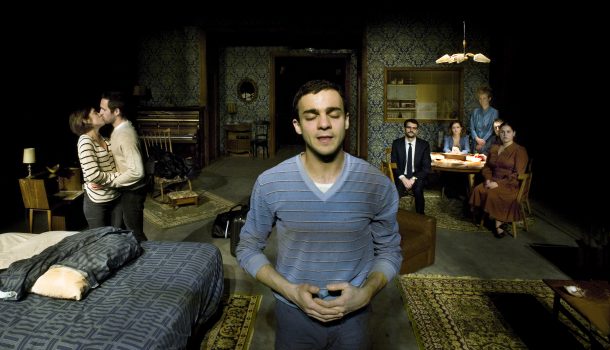

Claudio Longhi. Photo: Riccardo Frati. Courtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

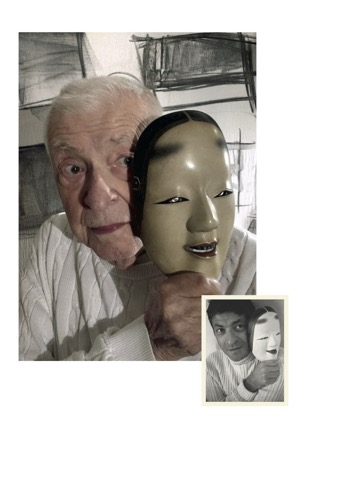

It will perhaps be useful to begin with some background about the Milanese theatre and its new director.[1] Il Piccolo – Italy’s first permanent theatre (teatro stabile) was founded in 1947 by Giorgio Strehler, Paolo Grassi and his wife Nina Vinchi Grassi and made “Teatro d’Europa” by ministerial decree in 1991. After Strehler’s death, a second phase began under the direction of Sergio Escobar, who led the Piccolo for 22 years, from October 1998 to July 2020, supported by the director Luca Ronconi as an artistic consultant. Since December 1st of this year, his direction has passed into the hands of Longhi, who, though he departed from the Piccolo in 2015, had worked there for more than eight years (from 1995 to 2002), collaborating with Strehler on the creation of such memorable productions as Quel pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana (1996), Lolita (2001), and Infinities (2002).

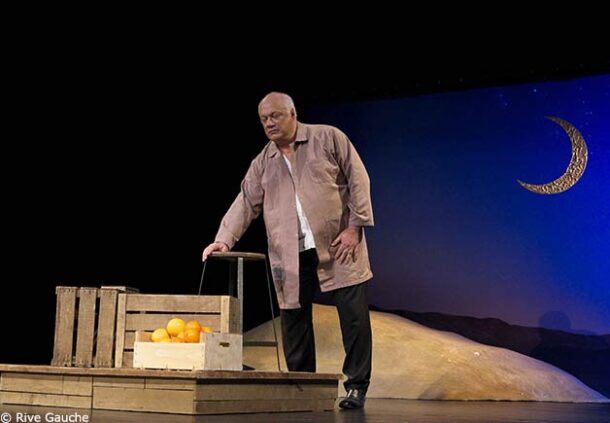

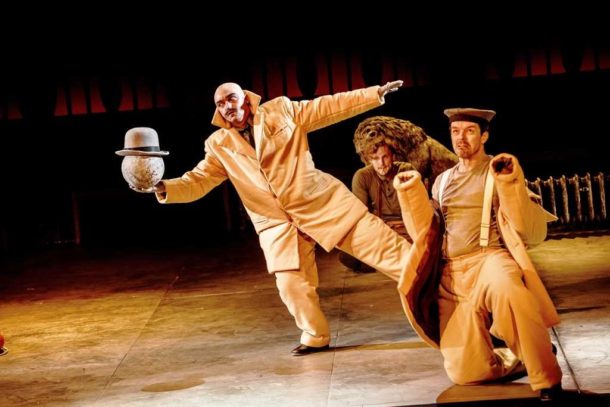

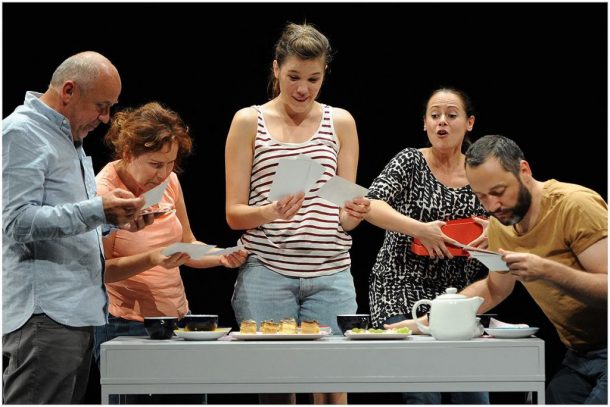

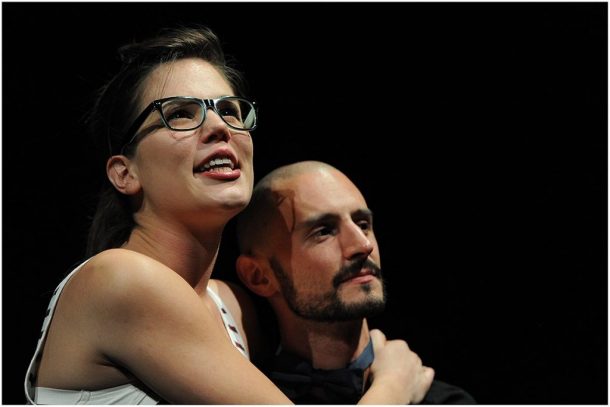

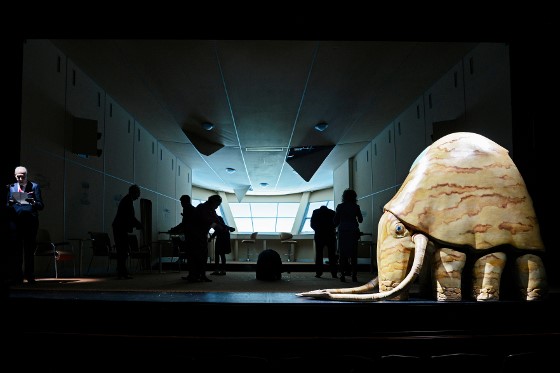

In Italy’s theatrical microcosm Claudio Longhi, 54, can be considered a young man. His career has been marked a very rapid rise and gaining the profile of a cultured artist, his interests divided between academy and stage. Named Full Professor of “History and Institutions of Directing” (a field of study introduced in the early seventies by the director Luigi Squarzina), he mainly dealt with the history of dramaturgy, directing and the actor.[2] At the same time, Longhi has directed performances for numerous national theatrical institutions, including the Teatro di Roma, the Teatro de Gli Incamminati, the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, the Teatro Stabile in Turin, the Teatro Due in Parma, the National Institute of Ancient Drama, ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro. Among his stagings have been Brecht’s Arturo Ui (with an excellent Umberto Orsini as the protagonist), Classe operaia va in paradiso, based on the film by Elio Petri in Paolo di Paolo’s adaptation, La commedia della vanità by Elias Canetti and, lastly, Il peso del mondo nelle cose by Alejandro Tantanian.

Many international theatre projects have been directed by Longhi since 2008, including the multiple project Il ratto d’Europa. Per un’archeologia dei saperi comunitari (2011-2014, UBU Premio Speciale 2013). His work as a theatrical pedagogue is also important. After teaching History of Theatre at the Scuola del Piccolo Teatro in Milan from 2005 to 2015, in 2015 – for the ERT Foundation – he took over the direction of the Iolanda Gazzerro School of Theatre in Modena “Laboratorio permanente per l’attore”. In this context, his artistic partnership with the actor Lino Guanciale, a constant presence in his most recent shows and in the activities of audience training and theatrical teaching directed by him at schools and universities, is of particular interest.

Longhi’s plans for the Piccolo – a theatre where he is well known and esteemed, thanks to the precious work carried out alongside Luca Ronconi when he was artistic consultant to the director Escobar – is structured around some points in particular, with the primary objective of relaunching and redefining the role of public theatre as a cultural mission. Among the most important ideas proposed, are the wide international vision with the possibility of a great festival, the creation of a stable company on the German model, a particular attention to the formation of the public and to the numerous professional concern that bring to life the theatrical microcosm. The chapter on what is to be learned artistically still remains to be written. By statute, however, the new role of manager will force him to be limited as a director; he can direct only one show per year.

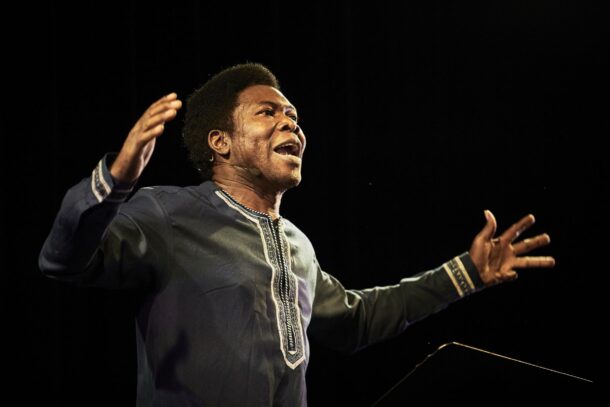

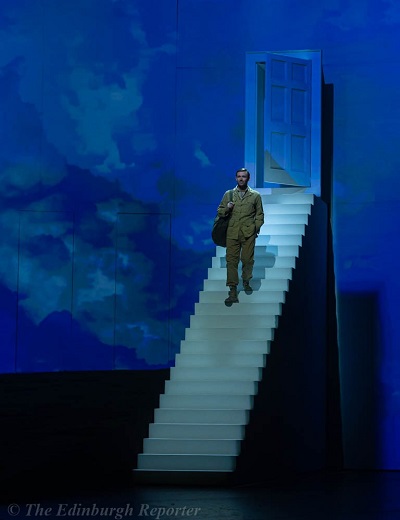

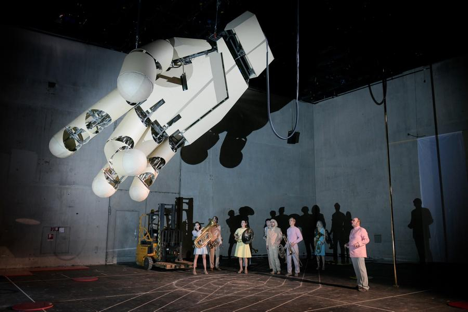

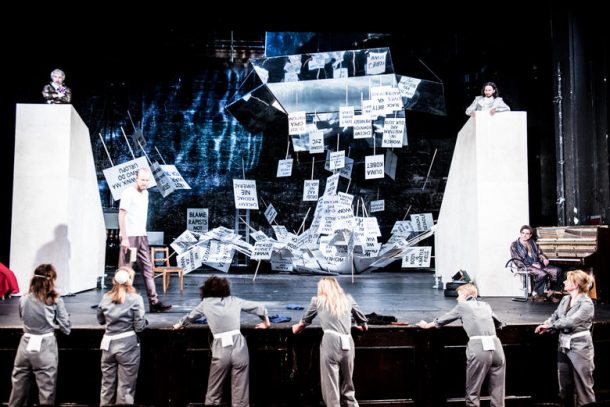

The theatre currently comprises three spaces: the “Teatro Studio Melato” (an experimental space that also houses the school of theatre), the “Teatro Strehler” (the main venue, inaugurated in 1998) and the “Sala Grassi” (the historical space on the Via Rovello).[3] Longhi wishes to clearly define the identity of these various locations in the Piccolo, redesigning and clarifying the geography of the three spaces: at Grassi the mission will be the consolidation of a canon, at the Melato the study of the new, and at the Strehler the presentation of strong European innovations.

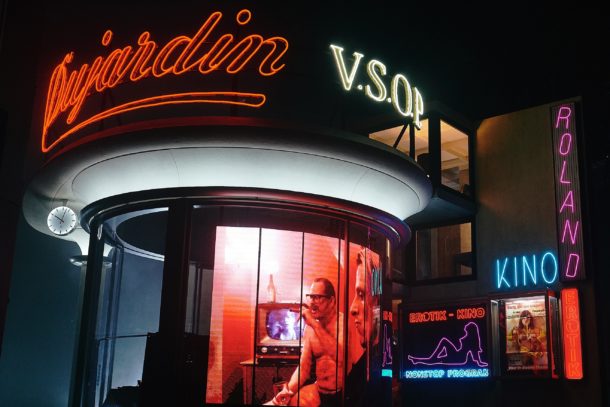

Exterior, Sala Grassi. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

The new director has all the qualities and skills necessary to lead the prestigious Milanese institution. His profile is that of a militant intellectual in the theatre, with a vision of renewing the public scene and a conception of open theatre, made up of a wide variety of interactions with the public, of insights that come out of the world of spectacle and is dedicated to developing, through theatre, the spectator and his knowledge of society more generally.

Certainly he does not face a small task. As much as he seems to enjoy the favor of the hundred workers of the Piccolo, the challenge is considerable and the road does not seem to be downhill. Behind him Longhi has the spectres of the various guardians of the Italian and international scene that preceded him, in a theatre that in just over seventy years has had only three leaders. Before him a mission for a courageous captain; to reform the Piccolo after bringing it out of a politically and economically complex situation. Viewed from above, 2021 will include the celebrations for the centenary of Strehler’s birth, while on the other hand this season is must operate on an international level, of interest to the whole world of theatre.

The following pages reflect on a recent conversation with Claudio Longhi on the future of the Piccolo Teatro, on its new direction, and on his experiences, just concluded at ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro.[4]

The Public Function of the Theatre

A central issue, already significant in the so-called “world before,” the world as it was before the pandemic – but which the situation in which we find ourselves has exacerbated and made it all the more topical – is the need to clarify and establish the public function of the theatre. This is a concern directly linked to the history of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano and its founding fathers, to the approach that Giorgio Strehler and Paolo Grassi have brought to the theatre, supporting and realizing it from an organizational and artistic point of view.[5]

It was during the second post-war period that the first public theatres were born in this country, called “stable” as opposed to private companies, mostly itinerant. Italian theatre had lagged somewhat behind other countries, especially with regard to modern directing, which had not yet developed in Italy. Fascism had held back the development of the theatrical landscape, preferring to subsidize private companies in order to guide their choices. Starting from this scenario, in the second post-war period the need for a theatre as a “public service” was thus prepared for; the Piccolo, municipally run, was both the first public theatre and the first stable theatre in Italy.

The programmatic intentions of the Piccolo Teatro were declared in the magazine Politecnico, where the desire to create an “art theatre for all” was emphasized. The repertoire should not include texts intended to be pure and simple escapism in order to please the public and thus guarantee a profit, as was the case with private companies. The Piccolo would be “art theatre.” Presenting itself as a theatre with only artistic ambitions, without speculative management, with a precise planning in the choice of shows. It would also be a “theatre for all,”[6] since ticket prices would be kept low and there would be the possibility of subscribing and receiving discounts. It was the opinion of Paolo Grassi, in fact, that the “people” did not stay out of theatres for cultural reasons, but only for economic ones.

Interior, Sala Grassi. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

Today, as then, it has become urgent to return to those programmatic intentions, trying to, in a Brechtian manner, return the sense of utility to theatrical practice. In Italy it is difficult to understand the function of culture and art in the broadest sense, and of theatre in particular. Until we come to define what artistic experiences are for, it will not be possible to clarify the thorny issue of the endemic fragility of theatrical practice in this country.

This is a concern that Grassi and Strehler have strongly raised thanks to their idea of public service of the Piccolo Teatro. This is a very topical problem, and one very close to the new director’s heart. On this subject he has said: «I think it is important to start from that original idea, to reaffirm the centrality of the theatre within the practices of community building and sociability. I wonder whether theatre is still a public service or whether that category is partly outdated. From this point of view, I have often thought about the fact that perhaps we should talk today not so much about community service but about the value of theatre to the community.»

This distinction is far from a sophisticated abstraction or based upon pure speculation. It has obvious practical repercussions, since the concept of service is closely linked to the idea of a supply that anticipates a demand. «I am convinced – continues Longhi – that at the moment there is a strong need for theatre, but there is not as clear and defined a demand for theatre. Or rather, there are questions about theatre, but looking at most people numbers you gain the perception that the theatre corresponds to an intimate need to which one struggles to give a name. I say this with good reason, because – as all the training experiences in schools confirm – when you meet people who do not know the theatre and start showing them concretely what it is, they become attracted to and develop a fondness for practical work with great strength and passion. In this sense, I am talking about a necessity that is not in question. But if it is not in question, it is also difficult to say that theatre is a service, because to be a service it would have to answer a question. Hence the concept of value serves as the founding element of a cultural identity and as a driving force for a dynamic of cultural development. Value can also be of use, but it is not necessarily service.»

Longhi’s statements demand a broader horizon, which concerns the possibility of conceiving theatre as a common good, not belonging to an individual or a government, but to a community. These are reflections on the public function, service, value, the common good of theatre as a field of exploration and investigation that makes it necessary today to disassociate ourselves from the practices of the past, to lay the foundations of tomorrow’s theatre, taking the pandemic experience as the starting point of a dynamic of progress of the scenic experience. «I am convinced – says Longhi – that it is a powerful field of exploration , within which to rethink the role of the theatre starting from Via Rovello, from the reality that first in Italy radically placed at the center the themes emphasized there, laying out the conditions for that theatrical system in which we live today, the offspring of the various reworkings of the ‘Piccolo Teatro’ model that in the forties of the last century was imposed at national level.»

Theatre as a place that is a generator of thought, a space of storytelling and dramaturgy

How, then, can the function of theatre be described today, what is the usefulness of theatrical practice? What is the theatre’s ability to once again take a place in the exercise and development of Community practices, interrogating the dynamics of the functioning of the community?

«Never more than in this moment, I believe it is essential to regain the ability to say ‘we’: this is precisely the political, public and civic function of the theatre» declares the new director of the Piccolo. For Longhi, this function must be directly linked to the ability of the theatre to become a place where thought is generated, understood primarily as reflections on “sociability,” which is a nodal and constitutive aspect of theatrical practice.

There has often been talk of the economic value of culture. One of the legacies that Covid has left us is that of becoming aware of the value of the dimension of work that is connected to cultural practices, just when it became understood that entire segments of the country’s production system were failing in relation to theatrical experiences. «I am convinced’ – insists Longhi – “that the entrepreneurial and economic contribution that culture in the broadest sense and theatre in particular can give to a country Iies not only in the fact that there is work related to the sphere of theatrical practices, but also in the awareness that theatre can generate thought. Thinking is the engine of a country’s growth: it is no coincidence that countries with a high index of cultural consumption are often also those with the highest gross domestic product.»

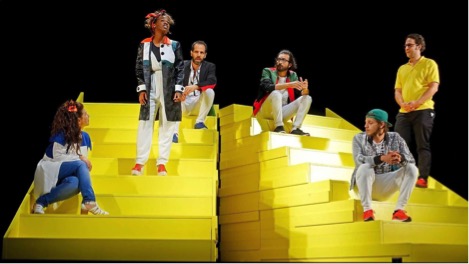

For Longhi, these aspects fall within that public function which needs to be reflected upon in a theatre like the Piccolo: «Obviously this node of issues branches off in various directions. On the one hand, the element of sociability leads us to reflect on the ability to become a community and a place that can serve as the generator of the theatre community. I am thinking of the beautiful pages that Fabrizio Cruciani dedicated to this theme in his book on the theatrical communities of the 20th century, which are a starting point of what theatre could be today.[7] I find this reflection on community theatre and the various participatory forms that have been promoted in recent years extremely interesting. They represent a revisiting of those practices of an animating theatre that were undertaken between the late 1960s and early 1970s, directly linked to the concept of decentralization desired by Paolo Grassi.»

Time has passed since those extraordinary years, time that has introduced changes that must be confronted. The idea of using participatory forms as a way of rebuilding the relationship with the public and educating the public is central and has been pursued in various ways during Longhi’s theatrical career: «I do not mind, with regard to the particular structure of Milan, reintroducing practices of this kind, which I also find appropriate to a certain model of urban development applied in Milan in recent years , like the idea of the “15 minute city,” the idea of a polycentric and scattered city». With this in mind, therefore, thinking about the future of the Piccolo, it becomes essential that the theatre comes out of the risk of self-referentiality that sometimes grows within theatrical practices, without, however, renouncing its own specificity: «Theatre must not set itself apart and become something else in itself. In all the participatory practices that I tried to put in place, the problem was to understand what the theatre could give more than other practices of sociability and intervention within the community, starting, however, from its own specificities.»

Cloister, Sala Grassi. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

At the same time, theatre has always had another fundamental function: that of telling stories, as a fascinating attempt to organize the chaos of the experience. Telling a story means finding logical and chronological connections in the flow of happening, and these connections are an attempt to put order into chaos. Never before have we needed orientation maps to move within the confusion that surrounds us.

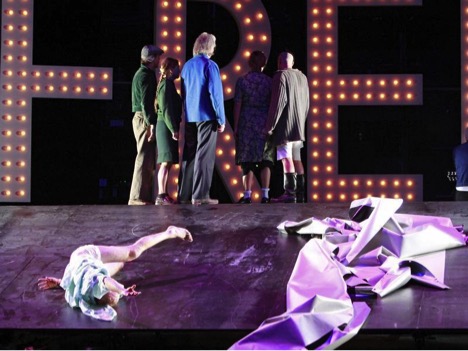

The theme of telling stories directly calls into question the question of the return of the centrality of dramaturgy in the theatrical experience. Longhi has always had a strong interest in dramaturgy, the new dramaturgy in particular. The latter can only take “critical” forms, such as revision and reinvention of the mechanisms of organization of the stage fabula experienced in the past. It is an attention that starts from the shared fundamental conviction that even the so-called post-dramatic theatre and the awareness of the “suspended drama” have in themselves a strong dramaturgical drive. As another way of articulating the dramatic form, the dimension of the story is underlying even the most radical experiences of post-drama, it is simply a different way of telling. Longhi states: «Gertrude Stein’s “Landscape Drama” also has a story, as well as the “description” can be a story in itself. The new way of telling stories cannot but take note of the adjustments that, from epic dramaturgy to post-drama, the experience of dramatic form has undergone during the last century and the so-called “Theatre of the Zero Years”. I’ve always been very attracted to this horizon.»

Longhi imagines, therefore, that the Piccolo di Milano can once again become a strong point of reference for the new dramaturgy: «I am very fascinated by the idea that the Piccolo is a place of intense confrontation with national, European and more generally international dramaturgy, with a view to mutual fertilization». Dramaturgy is, moreover, a peculiar and historically constitutive trait of Italian theatre, even if it lives on a series of “wasted inventions” – to quote a famous expression by Claudio Meldolesi – that struggle to settle in canon, with all the ambivalences that the word canon brings with it, as a place of constant vitality, but also as a trap within which one risks being imprisoned.[8]

Europe and internationalization

Longhi’s clear openness to crossing national borders directly raises the issue of internationalization. In the current legal framework, the “Piccolo Teatro di Milano – Teatro d’Europa” is part of the UTE (Union des Théâtres de l’Europe). The UTE itself is the daughter of the original impulse that started from the Piccolo and that sees the Milanese theatre and the Odéon in Paris as the leaders. Founded in 1990 by Jack Lang and Giorgio Strehler, who in particular worked for the creation of the Association, it is designed to bring together theatrical productions and European artistic works under the sign of cultural exchanges and the formation of a common cultural identity.

Exterior, Teatro Strehler. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

Historically, therefore, Il Piccolo di Milano has set itself the mission of operating on the internationalization front. This is a point about which we must question ourselves today and which we cannot ignore. Longhi says: «While there is a widespread need to rebuild a supranational community, the pandemic forces us to isolate, to take into account the strong travel restrictions. We must therefore ask what kind of sustainability community practices we will have in the world of tomorrow». The Covid crisis – emphasizes Longhi – marked a profound turning point in the relationship between man and nature. This crisis has highlighted extremely critical elements in the previous life system. The issues of gender jumping, the elimination of bio-diversity, the relationship between these and other issues with the deep crisis that has settled between man and his surroundings are very evident.” Longhi comments: «We will get over the Covid crisis, but we must treasure this opportunity to change, otherwise next time it will not be called Covid, it will be called something else, but we will be confronting the same problem. We’re on a running train, which is hard to stop, and there’s still a force of inertia in the previous life system that we are struggling to get rid of.»

Since the dramatic reality in which we are living will not change overnight, the theme of the environmental impact that international travel and tours carry with them is an issue that cannot but touch the theatrical universe closely. In reflecting on these topics, the new director thinks of questions that are being asked in this regard by artists such as Katie Mitchell in seeking alternative ways of imagining theatrical exchanges at international level: «Being at the head of a Theatre of Europe today one cannot ignore the question of what it means to create international relations at a time like the one we are experiencing , just as one cannot help but wonder what it means to be a European theatre today. In other words, it also means questioning Europe and the European identity itself.»

Theatre has played a decisive role in creating the identity of European culture: from classical Greek theatre to the experience of Renaissance theatre, to commedia dell’arte, to the Spanish Siglo de Oro theatre, to Elizabethan drama, to the great flowering of bourgeois drama in its various forms, theatrical practices and dramaturgy have played a profound role in the definition of European society and community , drawing boundaries and characterizing elements. Longhi says: «If I sit in the theatre and experience a character named Irina or Hedda Gabler I don’t feel anything separate from myself, distant from me, despite the fact that I am aware that I belong to a different cultural system. This is because there is a kind of European glue. Let’s think about the extraordinary function that commedia performers had in creating a cultural imagery. One of the founding myths of modernity, Don Giovanni, experienced series of “journeys” through Europe that have strongly conditioned our way of understanding. Mythologically, Cadmus founds Thebes while searching for kidnapped Europa. So, there is a kind of kinship between the founding of Thebes and the mythology linked to the Labdacids, which has occupied so much of our theatre along with the idea in particular of a kidnapped Europe […] The oldest dramatic text that has come down to us is The Persians, which with an extraordinary invention of estrangement interrogates European identity seen through the eyes of the East.»

What remains of this immense historical baggage? What does it mean today to be a European theatre? What role can theatres play in contemporary European cultural dialectics? Longhi says: «We live in a moment when, even in light of the pandemic crisis, we belong to a global village where there are areas that have deep characteristics and ancient identities, yet we are all within a single reality that goes from China to New York. But it’s one thing to live in China, another to live in Milan, another to live in New York. Theatre plays a fundamental role in these reflections, and I believe that being a “Theatre of Europe” today means engaging in focusing on questions of this kind.»

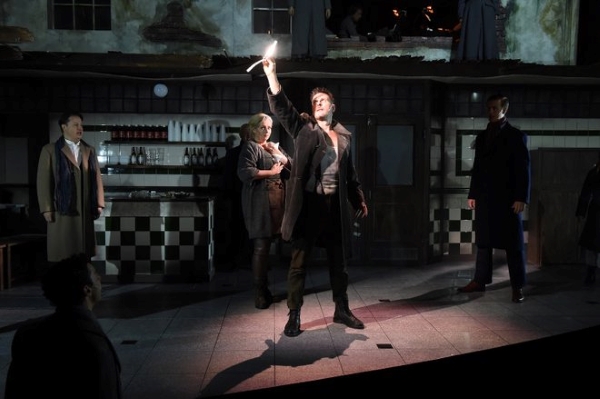

Speaking of internationalization, the Festival moment in the new direction of the Piccolo represents for Longhi a fundamental crossroads. In this case also, a gaze towards the future starts from the past experiences of the Piccolo, which already under the guidance of Escobar and Ronconi had accentuated its international dimension and vocation thanks to a series of events including the “Festival Teatro d’Europa.”

Interior, Teatro Strehler. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

Festivals being famously the strongest moments of dialogue with abroad, the new director plans to create and direct one, as he did with the “FESTIVAL VIE” during the recent years of his direction of ERT: «During a festival, in a short time a series of projects are carried out that facilitate foreign organizations in coming to us to see the Italian reality and make it possible for the Italian public to see what happens outside their country. Festivals are strong two-way crossing points, from the inside out and from the outside inwards. It is clear that the concept of the festival poses cost problems. We will have to hold discussions about this… In years when economies are precarious, like the years we are living now, I cannot say what space there is, but I would like to make one for the Piccolo, just as I would like to give space to dance.»

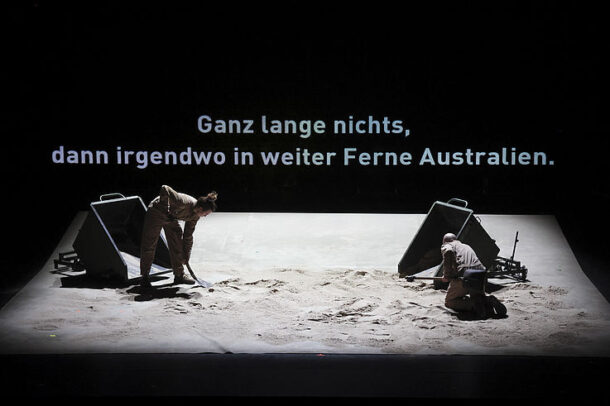

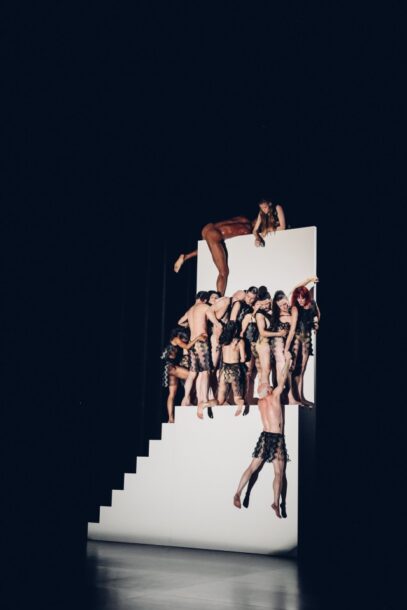

Inside the great lava flow that goes under the common label of “performance practices,” dance is probably today one of the most lively and interesting transformational faults. This has been demonstrated by the great names of the past such as Pina Bauch, and great names of the present, such as Dimitris Papaioannou, just to give some of the best known examples. Choreographic practices are today giving much food for thought on several fronts, including from the perspectives of the evolution of dramaturgy and directing. For Longhi it would be useful to consider, for example, the transformation, involution or crisis of the figure of the director through comparison with that of the choreographer. From choreography as well could come useful stimuli to comprehend dramaturgical practices. In this regard, he says: «The way our system is built, the world of dance and the world of prose – assuming it makes sense to talk about prose (from my point of view it makes no sense to use the prose category to catalog a certain area of theatrical operation) constitute an unhealthy separation, while from the contamination you could have very strong stimuli. Even if I am not an expert, I am fascinated by the panorama of contemporary dance and that panorama must be kept in mind, explored, encouraged.»

Training of the public and actors

In Longhi’s reflections on the responsibilities that the future Piccolo Teatro di Milano will have to assume under his direction, the theme of the formation of the public is central, growing from his observation of the crisis in the demand for theatre that has characterized Italian reality for years: «A theatre like the Piccolo must also remain a leader and example with regard to theatrical education at both the national and international level». Rightly, Longhi doesn’t make it so much a problem of box office money flowing into one theatre rather than another. The crisis in demand inevitably leads him to consider the formation of the public. The training is, in fact, one of the weaknesses of theatre in Italy, not so much in relation to the education of artists, but rather with regard to the theatrical literacy of the country. Italy struggles to confront the matter of arts education in the broadest sense and theatrical education in particular. Those who work in the university, for example, know perfectly well that as regards the so-called humanistic sciences (which in themselves are considered at the tail end of the training that makes the work possible) theatrical studies are considered to be “children of a lesser god” compared to the more respected disciplines.

This is an area that should be studied carefully and seriously. The matter of the formation of the public, in fact, points to a broader problem: that of the difficulty of our country in conceiving theatre as an organic part of the cultural system. At best, we always tend to regard theatre as a recreational activity, of greater or lesser quality, while we struggle to recognize theatre the status of a cultural experience in a serious sense. Longhi rightly says: «I recall that the theatre legislation provides specific support for joint projects between the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR) and the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MiBACT). I believe that, today especially, it is very important to link creative processes to a conceptual design that contextualizes them within a broader system of thought and reflection, in which the creative process is only the tip of the iceberg. I like to think that the Piccolo Teatro can become, or go back to being, a crossroads of heterogeneous cultural experiences that are in dialogue with the scene, but that can also be perceived as external to the scene and find from time to time in the scene their limits, their conflicts or their springboard».

The theme of cultural planning, in Longhi’s vision of the future Piccolo, is intimately linked to that of scenic practice in the strictest sense: cultural planning and scenic practices should be in a dialogue creating constant synergy. This vision of theatre as part of a broader cultural dimension will represent a fundamental hub in Longhi’s direction, aimed at interfacing and aligning the activities of the Milanese center with other European theatrical experiments: «As I have often said, Italian theatre has nothing to envy in the theatre across the Alps, it is instead our own theatrical civilization, I believe, that belittles and scorns itself, thus existing in a state of anomaly in comparison with the theatrical cultures of other European countries. A “Theatre of Europe” such as the Piccolo will have to work seriously on this front too.»

Exterior, Teatro Studio Melato. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

In recent months it has become common to talk about Covid as a disease that affects the older sections of the population. With regard to discussions about education, however, we soon realize that this is true only from a strictly medical and physiological point of view. Parallel to this, there is a social illness which has arisen among young people, and it is extremely powerful. The younger generations are a category fiercely affected by this pandemic. When we talk about education and the pandemic, let us think about the situation of schools, universities, conservatories and theatre academies. How much of their educational experience do young people now have to give up? «Distance learning is not bad,” says Longhi. A chapter could be opened here which would need more room for reflection and to which I will therefore return elsewhere. However, to simplify the matter greatly, it is critical to much of the training experience that you “get out of the house” and that you meet with your peers. This is precisely what is missing now, we will see the consequences in 15-20 years, when the people who are being formed today will begin to hold critical positions, places of responsibility in society and in the world of work. Young people today are a group under enormous pressure at the same time that we are on the threshold of a new world, which will have young people as its protagonists. For this reason, even more today, the training of the public and the theatre professionals is at a critical juncture.»

In 1987, Strehler founded the “Scuola per attori” at the Piccolo, which is based in the Teatro Studio, today named after Luca Ronconi. Claudio Longhi has been involved in the training of actors for years. He has therefore no lack of reflection, and brings a clear perspective on the system of complex competences that an actor must possess today. This cannot be summed up simplistically as possessing technical knowledge, limited to theatrical and performing practices. Instead, it is an orientation that keeps expanding and includes more generally a reflection on how the actor approaches society and on what role the actor must play in contemporary society, starting from technical training. It is a discourse that involves not only the actors, but all the professions of the theatre; Longhi, over the years, has always given ample space and recognition to the theatrical function of the “dramaturg” who, as a figure of mediation in cultural dialogue, is directly connected to the very way in which theatrical practices are oriented within society.

Longhi greatly esteems Carmelo Rifici, the current director of the “Scuola per attori” at the Piccolo, and with him he intends to collaborate in a strong synergy: «I believe it is necessary for the “Scuola del Piccolo” to exist in autonomy, within a horizon and as an artistic project that is the one that I will try to focus on and pursue in the coming years. Once I have drawn up its artistic and cultural parameters, it will be my responsibility to ensure the good functioning and effectiveness of the training trajectory of the actors and beyond. It will be important not to forget to constantly question how young people who leave that training can find a place in the world of theatrical work, with a secure place on the stage, within the horizon of meaning of the artistic and cultural project of the Piccolo di Milano. […] I always like to act in concert and in dialogue with the various institutions of the real situations in which I find myself operating, giving priority to internal concerns, but also in dialogue with external ones. I have often, for example, worked with or admired young people who trained at the “Paolo Grassi” in Milan. I am therefore pleased that we will be able to develop a dialogue with that School, while respecting each other’s specific characteristics.»

As has already been mentioned, in addition to having a career as director and director of National Theatres and Organizations, Claudio Longhi is also a university professor at the historic “DAMS – Discipline delle Arti della Musica e dello Spettacolo” in Bologna. With a view to enhancing the relationship between research, study, theoretical reflection, training and artistic practices, Longhi aims to further expand the activity of the Archive of Milanese theatre: «At the Piccolo I went there for the first time to see one of the many exhibits concerning Strehler’s The Servant of Two Masters. Later the Piccolo was a fundamental part of my artistic professional training. I attended it first as a student. The last part of my apprenticeship with Ronconi was at the Piccolo, in the late 90s, when he was still director of the Turin theatre. I then ended my collaboration with the Master when Luca was appointed Artistic Consultant of the Piccolo. This theatre is therefore for me a place of the heart as well as a professional one. I fully agree about the need to create a strong combination of theory and practice. That is my own history and I’ve been trying to do it all my life. The Piccolo’s archive is not easy to access. I repeat, I also visited it when I did my thesis on Ronconi, to consult the folder there on Furioso. Having now attended Italian theatres for a long time, I think the Piccolo probably remains the theatre that has one of the best organized historical archives compared to other Italian state theatres. I will take care to strengthen it further and investments will certainly have to be made in this direction as well.»

Interior, Teatro Studio Melato. Photo: Masiar Pasquali. Courtesy of the Press Office of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano.

One last aspect, although not the least, concerns the governance of the theatre. As is well known, the director of a building may delegate artistic or administrative functions to a person he or she trusts. This happens and has often happened in the past, not only at the Piccolo in Milan. But, as already mentioned, Longhi seems to want to take a different path in this regard: «One issue which I have already begun to discuss with the Board of Directors is governance. I wonder, in particular, whether it is still appropriate to support the director with an artistic consultant in the strict sense or whether it makes more sense to envisage a system of artists and residents with the support of a dramaturg colleague who can guide the choices or otherwise act as a stimulus for the choices to be made. […] In any case, there must be an internal confrontation with the structure of the theatre, which has not yet taken place. We are faced with a historical moment in which, also out of a sense of responsibility towards the operators of the production, the commitments made must be kept. There are already organized projects that due to Covid have not been realized this season and that will have to be scheduled for the next.» In light of these statements, it therefore seems premature to name one or more artists who may support Longhi in the programming and management of the activities of the famous theatre.

Recent experience at ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro

With the appointment of Longhi to the Piccolo, the Emilia Romagna Teatro loses its leadership, on which it counted for the next few years, and finds itself without a director during this strange 2020-21 season, still threatened by Covid. If, in fact, after the resignation of Sergio Escobar, the crisis in which the Piccolo had fallen during the summer has ended positively, a complex phase is now opening to identify Longhi’s successor at the head of the numerous theatres of Modena, Bologna, Cesena, Castelfranco Emilia and Vignola, spaces in which the various activities of the Foundation are carried out.[9]

It will not be easy, in fact, to find a figure who measures up, a personality with a strong international profile, who knows how to build up the legacy of an innovative and distinguished artistic tradition, capable of coordinating theatrical seasons, international projects and festivals and the multiple training activities carried out in recent years by ERT. Among the most likely names are that of the Cesenate director Romeo Castellucci, founder of societas Raffaello Sanzio, an artist of clear world renown, that of the director Antonio Latella, who has many years of experience in organizing the Venice Biennale, also of national and European renown and with an excellent knowledge of ERT, that of Silvia Bottiroli, a leading figure in the world of theatre, for years head of the Santarcangelo Festival, distinguished in her capacity for coordination and organization.

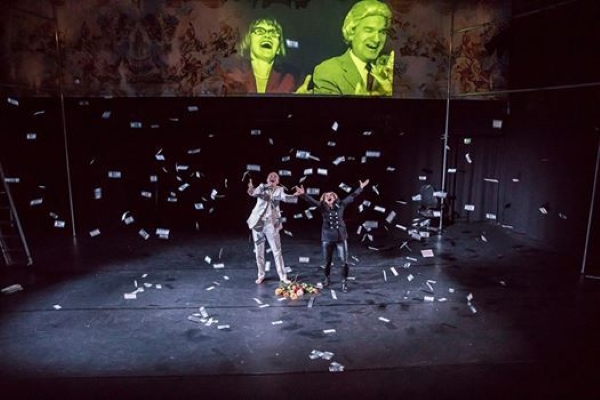

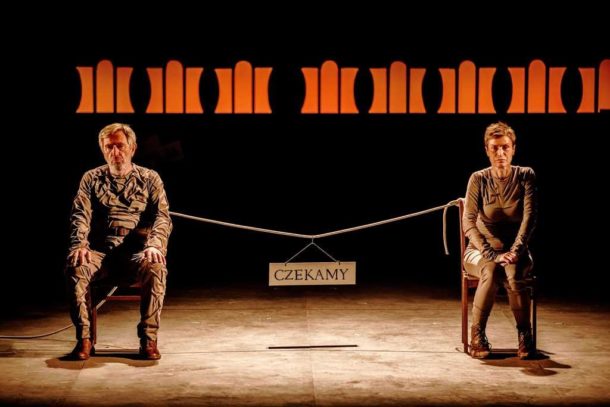

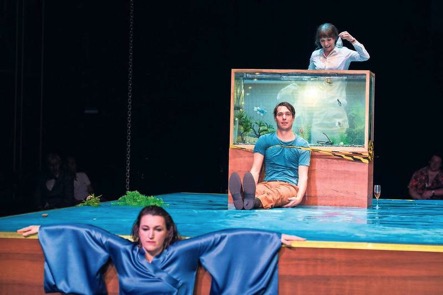

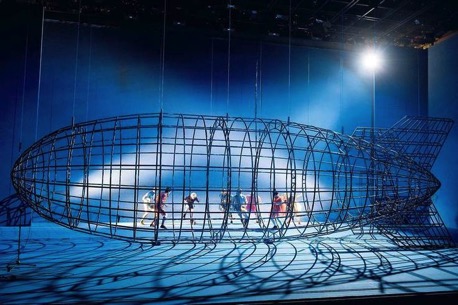

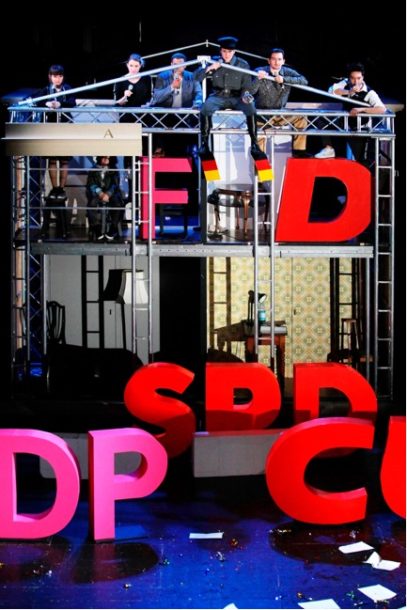

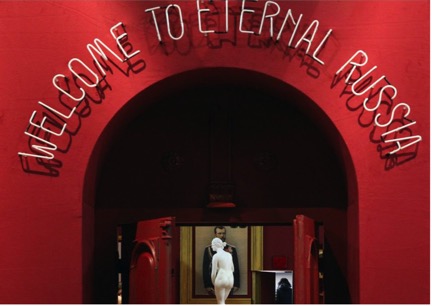

In the four-year term 2017-2020 during which he was head of the Foundation, Longhi carried out on several fronts a high-profile work, demonstrating that he knows how to interact with the major cultural and institutional establishments, both on the ground and at a national and international level, thus allowing ERT to be recognized in the ministerial ranking as “the first Italian theatrical establishment.” The projects carried out by the participating theatres in recent years have involved and mingled Bolognese and Modena society in a vital and pervasive way and the European projects previously inaugurated have gained new life and momentum.[10] The idea of theatre understood as “agora” and a powerful look at Europe and the world have characterized the theatrical seasons and the international theatre festival “Vie”, which he directed.[11]

Teatro Arena del Sole di Bologna (1904). Photo: ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro. Courtesy of the Press Office of the ERT.

An important and innovative part of the most recent activity of Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione has been theatrical training. The projects, aimed at training young actors “on the ground,” offer them opportunities for further training and professionalization. Since 2015, of particular importance has been the “Iolanda Gazzerro Theatre School, permanent workshop for the actor,” directed by Claudio Longhi, in which specialization courses for actors and dramaturgs are offered.

The attention to training at ERT is also indicated by the intensive programming of Teatro ragazzi. Its production and hospitality activity is rich with proposals for young people and teachers, aimed at developing suitable tools for reading the languages of the theatre: workshops, seminars, internships, conferences have been interspersed with shows, developing new perspectives and more conscious spectatorship. In recent years, tradition and innovation, shows and school have pollenated each other, giving life to an intense relationship with the public, as is appropriate for an idea of culture that builds communities.

According to Longhi, however, it is too early to take stock of his experience as artistic director at the Emilia Romagna Teatro: «We should look at this period from a little distance; I still feel too involved. I therefore cannot yet make an objective judgment. These days at the end of November I am working on the construction of the ERT 2021 budget, so I find it difficult to consider my management a closed experience». Yet, if it is too early to take stock, in the course of this directorship there have been important changes at ERT, which have taken place as the result of a path toward identity and cultural policy that has remained essentially true to itself.

As mentioned, ERT is famously a multifaceted and complex theatrical entity, strongly rooted within the region – or rather, it reflects different regional characteristics, since it organizes the activity of theatres scattered in several cities of Emilia Romagna – but also able to interact with the outside world, at an international level. More than anything else, it is this dual orientation, a kind of trademark, that has made it possible for Longhi’s path to cross in past years with that of the Foundation. At a national level, Emilia Romagna Teatro had probably the orientation best adapted to a certain way of thinking about the theatrical experience. For example, the many participating theatre projects carried out were created not by chance at ERT, but emerged due to the very orientation of that structure. Similarly, at the international level, the Festival Vie has proved to be a cohesive space-time reservoir, thanks to which important cultural and theatrical exchanges have been possible.

Longhi guided ERT at a time of strong growth: «I like to think of the transformation that ERT had in the aftermath of the 2014 reform, the reform involving the establishment of national theatres, as a teenage phase in which, just as happens to adolescents who grow up very quickly, ERT made a rather naive quantitative leap in the development of its production structure. This development started as early as 2015, that is, before I took office as director, and it continued into the years of my management». Such strong and fast growth created both organizational and structural problems. Longhi was able to accommodate these changes, helping the structure define itself at a time when it had taken a leap forward to adapt to the reform itself, which called for more and more production. But he has also encouraged the Foundation to implement a radical “change of skin:” many top ERT figures have retired in the years of his management. A very rapid generational renewal has therefore taken place. Again, Longhi was able to lead the Foundation so that it did not lose its center of gravity, remaining within its vocation: «I never had the ambition to give tears or to mark deep discontinuities, I simply tried to interpret, according to my sensitivity, a function and the address that ERT had manifested before me. The results achieved are certainly not thanks to me, but to those who have spoken before me. It is they who have created the conditions to achieve their recent goals».

On the other hand, there were many innovations carried out during Longhi’s of ERT. Among these, leading examples were the establishment of the Permanent Company, the Courses in Dramaturgy and the recently realized focus in the field of training due to its internationalization (a sort of roundup of honored authors). Think, for example, of the South American project that marks the current 2020-21 season, with the Courses of Calderon Blanco, those of Lisandro Rodriguez, that are being held right now, or the course of the Brazilian Antonio Araujo (which was supposed to take place this season, but which unfortunately will not materialize due to the Covid emergency). Think, also, of the many dialogues organized with the students of the DAMS from the University of Bologna.

Teatro Storchi di Modena – Emilia Romagna Teatro. Photo: Futura Tittaferrante. Courtesy of the Press Office of the ERT.

Many things have been undertaken, which are stimuli, possibilities, pathways that have been opened thanks to Longhi. Those who take on the direction of ERT after him, can decide to continue going in the same direction, adjust it or abandon it to head somewhere else. Longhi comments on this: «I am not fond of the idea that what I have done must necessarily continue after me. In my direction, I have tried to interpret what seemed to me to be a political mandate, to act as a cultural guardian vis-à-vis the city and regional context. I think it’s important to clarify your goals and look for your own way of staying faithful to those goals. […] I thank the entire ERT team for the priceless and wonderful way in which they have been close to me in recent years, sometimes with great momentum and passion, sometimes with difficulty, even with divergent points of view, but always in a climate of collaboration, constructiveness and adherence to a cultural project that I could hardly have wished to go better. I also thank those who accompanied me institutionally, President Giuliano Barbolini, who was a valuable road companion in very complicated moments, from the important external and internal structural moves, to the complicated current management of emergencies related to the pandemic.»

Claudio Longhi must be thanked for what he has done in recent years at ERT and wished a heartfelt “good luck” for the exciting and difficult challenge that awaits him at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan.

Daniele Vianello, vice-president EASTAP (European Association for the Study of Theatre and Performance), is Professor at the University of Calabria (UniCal), where he teaches Performance History, Drama, and Staging Technique and Theory. He has also taught at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” (2002-2008) and at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice (2015-2016). He is member of the editorial board of European Journal of Theatre and Performance, contributing editor and member of the advisory board of European Stages, Olhares, Biblioteca Teatrale, Rivista di letteratura teatrale, among others. His publications, centered mainly on Renaissance and contemporary theatre, include L’arte del buffone (Bulzoni, 2005) and Commedia dell’Arte in Context (eds. Balme, Vescovo, Vianello, Cambridge University Press, 2018). He worked for several years with the Teatro di Roma (Union des Teatres de l’Europe), where he assisted Italian and foreign stage directors (including such figures as Eimuntas Nekrošius).

[1] Concerning the history of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, reference should be made, in particular, to G. Guazzotti, Teoria e realtà del Piccolo Teatro di Milano (Turin: Einaudi, 1965); L. Cavaglieri (ed.), Il Piccolo Teatro di Milano, (Rome: Bulzoni, 2002); A. Benedetto, Brecht e il Piccolo Teatro: una questione di diritti (Milan: Mimesis, 2016); S. Locatelli, P. Provenzano (eds.), Mario Apollonio e il Piccolo teatro di Milano. Testi e documenti (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2017). From a critical point of view, the pages that Claudio Meldolesi dedicates to the development of Grassi and Strehler and to the foundation of the Piccolo Teatro remain essential in many respects: cf. Id., Fondamenti del teatro italiano (Rome: Bulzoni, 1984).

[2] Among Longhi’s main publications, see the volumes La drammaturgia del Novecento Tra romanzo e montaggio (Pisa: Pacini, 1999), Tra moderno e postmoderno. La drammaturgia del Novecento (Pisa: Pacini, 2001), L’Orlando furioso” di Ariosto-Sanguineti per Luca Ronconi (Pisa: ETS, 2006).

[3] On January 26, 1947 the Municipal Council announced the establishment of the “Piccolo teatro della città di Milano,” placing its location in the Palazzo Carmagnola in via Rovello n. 2. As is well known, the name “Piccolo” refers to the small size of the theatre.

[4] This interview took place on November 15, 2020. I have been authorized by Claudio Longhi to publish the main parts of it here, using «quotation marks» to indicate his exact words.

[5] On this subject see the recent study by S. Locatelli, Teatro pubblico servizio? Studi sui primordi del Piccolo Teatro e sul sistema teatrale italiano (Milan: Centro delle Arti, 2015).

[6] M. Apollonio, P. Grassi, G. Strehler, V. Tosi, “Lettera programmatica per il Piccolo Teatro della città di Milano”, in Il Politecnico, January-March 1947, n. 35, p. 68. See S. Locatelli, P. Provenzano (eds.), Mario Apollonio and the Piccolo teatro di Milano. Testi e documenti (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2017), pp. 115-28. “Politecnico” was one of the main magazines (first weekly, then monthly) of politics and culture that came out in Italy in the immediate post-war period, founded by the writer Elio Vittorini, and published in Milan for Einaudi from September 1945 (year I, n. 1) to December 1947 (n. 39).

[7] Fabrizio Cruciani, Teatro nel Novecento: registi pedagoghi e comunità teatrali nel XX secolo (Rome: Sansoni, 1985).

[8] C. Meldolesi, Fra Totò e Gadda: invenzioni sprecate del teatro italiano (Rome: Buzoni, 1987).

[9] Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione was founded in 1977 as a center of theatrical production, with the intention of supporting the prose theatre in the region. Its production venues are the Teatro Storchi and the Teatro delle Passioni in Modena, the Teatro Arena del Sole in Bologna and the Teatro Bonci in Cesena. By decree of the Emilian Municipality and ATER (Emilia Romagna Theatre Association), ERT became an Autonomous Body in 1991, and then became a Foundation in 2001. In 2015 it was recognized as a National Theatre and, in addition to the prose sector, also dedicates space to dance.

[10] Particularly worth mentioning here is the ”Prospero Project,” a European cultural network inaugurated in 2007 and aimed at developing intercultural dialogue through the mobility of artists or technicians and the exchange and dissemination of cultural productions. The project was conceived with the aim of promoting the circulation of works and artists, supporting a common cultural heritage and at the same time encouraging intercultural dialogue and promoting different cultures, contributing to the development of European citizenship. The project includes the Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione (Italy), the Théâtre Nationale de Bretagne (France), the Théâtre de la Place (Belgium), the Centro Cultural de Belém (Portugal), the Tutkivan Teattertyön Keskus (Finland), the Schaubühne (Germany).

[11] Inaugurated in 2005 by the Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione, the “Vie Festival” takes place in Bologna, Modena, Carpi and Vignola. The event is dedicated to the contemporary scene and its reflection in the theatrical forms and artistic expressions that gravitate around theatre, dance, performance and music, trying to capture its newest manifestations, with the aim of drawing the map of a theatrical territory – international and national – and developing its protagonists.

European Stages, vol. 15, no. 1 (Fall 2020)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Philip Wiles, Assistant Managing Editor

Esther Neff, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 74th Avignon ‘Festival,’ October 23-29: Desire and Death by Tony Haouam

- Looking Back With Delight: To the 28th Edition of the International Theatre Festival in Pilsen, the Czech Republic by Kalina Stefanova

- The Third Season of the “Piccolo Teatro di Milano” – Theatre of Europe, Under the New Direction of Claudio Longhi by Daniele Vianello

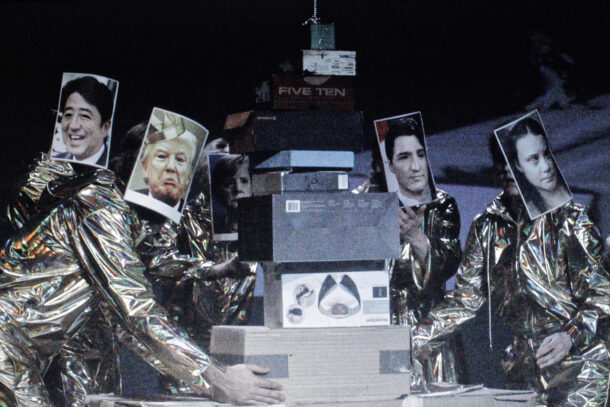

- The Weight of the World in Things by Longhi and Tantanian by Daniele Vianello

- World Without People by Ivan Medenica

- Dark Times as Long Nights Fade: Theatre in Iceland, Winter 2020 by Steve Earnest

- An Overview of Theatre During the Pandemic in Turkey by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Frankfurt by Marvin Carlson

- Blood Wedding Receives an Irish-Gypsy Makeover at the Young Vic by María Bastianes

- The Artist is, Finally, Present: Marina Abramović, The Cleaner retrospective exhibition, Belgrade 2019-2020 by Ksenija Radulović

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2020

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu