By Daniele Vianello

The 2020/2021 Season of ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro opened with the world premiere of Il peso del mondo nelle cose (The Weight of the World in Things), a new production by Claudio Longhi with original dramaturgy by Alejandro Tantanian.[1] Staged at the Storchi theatre in Modena from 29 September to 11 October, the show involves seven actors from the permanent company of ERT – Simone Baroni, Daniele Cavone Felicioni, Michele Dell’Utri, Simone Francia, Diana Manea, Elena Natucci and Massimo Vazzana – with Renata Lackó alternating with Mariel Tahiraj on the violin, and Esmeralda Sella on the piano.

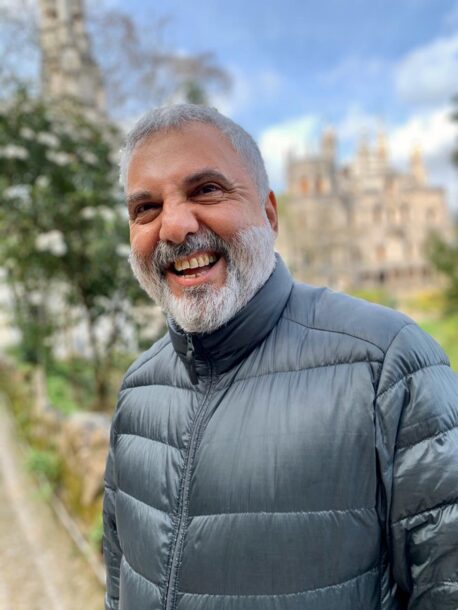

It is an ambitious project conceived by two leading artists on the international theatrical scene. Claudio Longhi is director, theatrical pedagogue and university professor; he was artistic director of ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro from 2017 to 2020, and since December 1st of this year he has been director of the famous Piccolo Teatro di Milano.[2] Alejandro Tantanian, from Argentina, is a playwright, director, singer, teacher and translator; from 2017 to 2020 he directed the TNA / Teatro Nacional Argentino – Teatro Cervantes in Buenos Aires.[3]

Claudio Longhi. Photo: Riccardo Frati. Courtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

Starting from two stories by Alfred Döblin, A Tale of Materialism and Trafficking with the Afterlife, Tantanian and Longhi, artists who share the idea of an open, lively and dynamic theatre, in close dialogue with the present and the community, develop an unprecedented portrait of our time, reconceived from new points of view. Thus, in the light of the dramatic events we are experiencing, they imagine a bright future in which human beings find their relationship with mystery and recognize the immense and inexorable rulership of nature.

Between 1940 and 1945, Döblin, a German of Jewish origin in exile in the United States, experienced with great discomfort the impact of industrialized American civilization, while in Europe the Nazi-fascist fury raged. In those years, with his penetrating sense of humor and with the sharpness of his critical gaze, he created two extraordinary literary inventions. To do this, he utilized popular genres: the fairy tale, the fantastic story, the thriller, giving them a new impulse and untried forms.

In A Tale of Materialism (published in Italy by Ibis)[4] Döblin chooses a strategy of entertainment to explore the breakdown in the balance of the relationships between nature and civilization, between science and life, and to investigate with humor the spectres of chaos which he felt surrounded him. The text tells a kind of strange strike by nature, which discovers that it is made of atoms, because this was the insight of Democritus. This position of radical materiality puts nature in crisis. It stops working and we witness a kind of epochal upheaval, in which disorder overturns reality. The human species is isolated, overwhelmed, unable to understand or act. At the very moment when the disarray is such as to raise the very possibility that men will wage war, men back down, withdraw. Democritus’ theory and everything strangely returns to an “after” that feels like a “before.” A sudden truce restores order, but it is no longer the same as before; there is a new awareness of the relationship between human beings and reality; things have inexorably changed.

Trafficking with the Afterlife (published in Italy by Adelphi)[5] is an occult thriller, a swirling detective-story full of humor. In a small town in the English provinces, during the Second World War, an inexplicable crime is being investigated, the murder of the brewer van Steen, found with his head smashed. In a sort of parody of a detective drama, the investigation focuses on a series of bizarre spiritual sessions, animated by paradoxical surprises, during which the forces of the afterlife seem to take over. The police end up asking the circle of local spiritualists to create a spiritual session in which to summon the dead man and be told by the deceased himself who killed him. Here too, as in A Tale of Materialism, pandemonium results, because during the spiritual session we witness a revolution and an unforeseen antagonism between the living and the dead. The world of the dead is presented to us in a joking way, as a picturesque community that wants to overthrow the world of the living. This introduces chaos into the investigation of the death of the brewing protagonist – who does not know that he is dead, and feels only what it is like to have left for a journey and to be simply “elsewhere.”

From the blending of these two texts comes The Weight of the World in Things, a contemporary fairy tale that, as Longhi explains «plays with the conventions of theatre – from cabaret to melodrama – to reflect on the power and function of imagination in the relationship with reality, calling together spectators into a kind of party: an invitation to the permanent celebration of the theatre, a show seeking to return to the belief in the power of fantasy.»

There is quite a bit of middle Europe in the show, starting with Renata Lacko’s violin (alternating with Mariel Tahiraj) and Esmeralda Sella’s piano, which accompany the performance with studied counterpoint, based on interspersed songs with a clear Brechtian flavor. The references to Brecht and the epic theatre go far beyond the cabaret scenes, however. The mimetic narration is continuously shattered by diegetic inserts, captions that comment and create distancing and possibilities for reflection. It is therefore an ambitious dramaturgical and directorial project, which perhaps at times would have required a less puzzling gathering of material and a more uniformly experienced company, but which as a whole is an indisputably successful show.

From the dramaturgical project to the production

The work on dramaturgy, rehearsals and the performance was the subject of a long conversation with Claudio Longhi, of which I report here some of the main elements.[6] The director says: «By choice, I have always avoided drawing clear lines of distinction between my private life and my professional life, between my daily life and the theatre. For me they are a kind of great continuum, one continuously blends into in the other. This show came at a very particular moment in my life because my appointment as director of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano took place while I was rehearsing the show». It was beautiful, but sometimes also heartbreaking for Longhi to work with the young actors of the “Iolanda Gazzerro School of Theatre – Permanent Laboratory for the Actor” of ERT, a school he directed from 2015 until his recent appointment as director of the Piccolo Teatro.

Alejandro Tantanian. Photo: Ernesto Donegana. Courtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

Fundamental to the realization of the show was the meeting with Alejandro Tantanian, with whom the director collaborated for the first time. Despite the forced distance, due to the pandemic and lasting the entire period of rehearsals and production, a kind of intellectual and emotional friendship was created between the two artists: «It is the first time that Alejandro was not present at the opening of his show; he decided to stream in from Buenos Aires. He could not participate in the rehearsals, because at that time he was in lockdown. I thank him for what he has made available to me with great generosity; playwrights are all too often jealous of every comma of their texts. Instead, he gave me great freedom and we immediately created a strong harmony of interests».

Longhi says he met Tantanian in France in 2017, a few months after taking office as director of Emilia Romagna Teatro. At the time Tantanian was director of the Teatro Nacional Cervantes in Buenos Aires. Between the two was born instinctively a great sympathy, both newly elected directors, both with a driving ability and with the desire to change the organizations that they were called to direct. The Teatro Nacional Cervantes directed by Tantanian is an institutional and conventional theatre, decidedly academic in nature, while he is one of the noble fathers of the new course of Argentine dramaturgy, made up of many little-known names, no less interesting than the best known artists. It was Tantanian who made the dramaturgical world of Argentine “teatristes” rise to national notoriety; it was he who brought a strong shock to a conventional structure like the Teatro Nacional.

The two directors wanted to collaborate, realize projects and exchange productions. Unfortunately for Tantanian, the experience of conducting the Teatro Nacional ended in a stormy manner last December. Longhi says: «We had last seen each other in Buenos Aires in January. He had just closed his experience of directing at the Teatro Nacional Cervantes, and shortly after we were overwhelmed by the events related to the pandemic. When I found myself thinking about the 2020-21 season, wanting to reflect on the epochal times we are experiencing, it occurred spontaneously to propose to him a project to be realized together, also in light of the interests I have in Argentine theatre, approaching him and asking him to create a text.»

The Weight of the World in Things. Photo: Francesca Cappi. Courtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

Longhi and Tantanian’s was an experiment and a borderline collaboration: the project, to compose a text and starting from that building a production, took off late in relation to the programming and production times. Following the pandemic, playwright and director were hit by emergencies involving what was happening: «These were not simple steps; I presented to him with a basic idea. In the show I would have been delighted to talk about the radical change in the relationship between human beings and nature and the redefinition of natural balances. I was very impressed during the lockdown to notice how the animals, by virtue of the fact that people had retired, were reclaiming spaces that had been stolen from them. It is impressive to imagine that a dusting of matter such as a virus has created such a collapse in the planetary system.»

Longhi recounts how these and other reflections had brought him back to his old reading, Döblin’s A Tale of Materialism, a critique of materialism in the strict sense (a novel that, moreover, appears significantly in the years of the German writer’s conversion). That novel stimulated Longhi to read another text by the same author Trafficking with the Afterlife: «Speaking with Alejandro, I presented myself with the two stories and told him that I would like to start from these, combining them … or start from just one of the two and blend it with another longer story, which would describe the history of the twentieth century. He said ‘I understand you’… In fact, reading those stories, he was seduced by another text concerning spiritism, the diaries of Victor Hugo, dedicated to spiritual sessions after the death of his daughter.»

Tantanian imagined a dramaturgy that intertwined the two starting texts of Döblin provided by Longhi with suggestions from Victor Hugo’s Contemplations. These parallel tracks converged creating a sort of great fantasy festival. Longhi explains: «My production is faithful to the text of Alejandro, who in turn is faithful to Döblin’s novel. I have made only small cuts, mostly of simplification, except for some parts concerning the A Tale of Materialism and the songs, which were the result of a collective writing with the actors. We had, however, a superabundance of material. Therefore, we decided to divide the show into two evenings, building it on an alternation of cabaret scenes and spirit scenes. In the cabaret scenes we also operated based on improvisations and exercises.» Divided into two parts – though essentially indivisible if you want to grasp the sense of its creation – the show finds in the almost serial multiplication of duplicity its own peculiar structure.

The sections of the script concerning the A Tale of Materialism are closely based on Döblin’s original. It is an operation in some ways similar (although of a completely different design) to that carried out in some of the stagings by Luca Ronconi, Longhi’s master. I am thinking in particular of Gadda’s Pasticciaccio, Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Gombrowicz’ Pornography; in those productions the novel was literally “staged” by the director in its entirety, attributing to the various characters both the dialogues and the parts narrated in the third person, instead of a conventional adaptation, which would have provided for the transfer of the story to the first person and the present.[7]

The Weight of the World in Things. Photo: Francesca Cappi. CCourtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

Also in the case of Longhi’s show, the choice made for the staging of Döblin’s short stories is not that of an adaptation, or a simple summary. Instead, it is a complex operation of segmentation and distribution of the text, faithful to the original novel, as regards the hidden and diegetic parts, which are divided among the characters (in particular between Augustus and Facciabianca, clown characters of an unusual cabaret). The director says: «Döblin’s story is certainly longer, but not so much, because it is a small pamphlet. In the script, the A Tale of Materialism turns out to be almost literally the text, with some cuts. In the preliminary text that Alejandro provided almost the whole novel was present. I then cut it here and there. In the end, there is a good seventy percent of Döblin’s original text in the show: it’s no small thing.»

As Trafficking with the Afterlife, Döblin’s work is present in its entirety, but it has been largely re-designed and reassembled, in a strange sort of hybridization with the biography of Victor Hugo, creating a typically South American story. The protagonist, in this case, is a disturbed family that turns to a medium to solve a family crisis born from the death of a daughter and another unlikely cataclysm in progress, not clearly identified.

In creating the overall scaffolding of the text Tantanian acted as a pure playwright, while leaving room for the desire and the ability of the director and the actors to invent, intervene and rewrite some parts, especially with regard to A Tale of Materialism and the cabaret scenes of comic characters (Democritus, Augustus and Whiteface). Longhi reveals: «It was Aleandro who reminded me that he was working with an Italian translation of Döblin’s works, moreover with very tight deadlines. He confessed to me that he struggled to create a gap between the language of comic characters and the Italian translation of the German novel, which he felt was literary, but for which he could not find a Spanish counterpart. Speaking about the jokes of the comedians and especially the character of Democritus – a character that was supposed to function as an alienating element of the A Tale of Materialism – he told me: “It is far more appropriate for the actor who will play Democritus to improvise, I can not give you the jokes, much better if I provide subjects. You should work from the improvisations of the actor.” That’s exactly how it went: the dramaturgy is Alejandro’s, but he gave me license to treat it as material for a set-up.»

To counterbalance the supernatural tinges and tension of Döblin’s tales, a series of cabaret-style comedy intervals were “improvised.” Often, during the show, laughter helps to scroll through the narration of the most serious scenes, built mainly on the Trafficking with the Afterlife. An extraordinary master of ceremonies, Michele Dell’Utri as Democritus, entertains the audience, appearing and disappearing at will between scene and forestage, interrupting the dialogue between Augustus and Facciabianca, who tell the A Tale of Materialism. Almost all of Democritus’ interventions and the answers given to him by Augustus and Facciabianca are the result of improvisations and were put together directly during the rehearsals. The songs were also reworked: «Alejandro wrote lyrics in Spanish, but he didn’t have any music in mind. Thus the texts have proved to be untranslatable in many respects. The playwright provided a subject for which we had to find the musical counterpart and a linguistic coating, because otherwise the rhyme and structure of the verse could not have been found.» Live music makes a fundamental contribution to the success of this show.

The Weight of the World in Things. Photo: Francesca Cappi. Courtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

Longhi’s direction accentuates the irony and parody of the genres that mark Döblin’s tales, managing several times to create an atmosphere of lightness not present in the beginning texts. The dramaturgy developed by Tantanian, from this point of view, is more ambiguous than its stage realization. In fact, especially in the part that derives from the Trafficking with the Afterlife, the script is literally a real melodrama, so overloaded that it becomes almost ridiculous. Longhi comments: «The directorial solution I could have adopted was twofold, it could have gone in two opposite directions. I could have worked on the materials I received by dramatizing them and taking their contents for real; or I could have created a production in the manner of an Almodovar movie. With the consent of Alejandro, we created a variation on an Almodovar movie. We started from the music: the musical accompaniments of the spiritual sessions were to be “bolero,” alternating with more serious melodies, classical music […]. What I wanted to realize was a kind of great soap opera style event from a South American telenovela, deeply ironic. I wanted to ironize the musical form, in the spirit of Döblin’s writing, whose lyrics are parodies: Trafficking with the Afterlife is a parody of a detective story, A Tale of Materialism is a parody of an epic didactic poem. Even this show could only be conceived as a parody of a genre, partly already embedded in the dramaturgy provided to me by Alejandro. […] His script, however, is a very elusive object, sometimes I wondered if I wasn’t putting in too much, if I wasn’t moving off of the dramaturgical track that had been provided to me, beyond the fact that the comedy tone is more in harmony with my nature than the dramatic one. But I think it was a way of keeping me in line with the text.»

In Longhi’s previous stagings the dramaturgy of space was largely confined to the scenography, to the stage machine as the defining element. In this show, on the other hand, spatiality is realized above all by the presence of the actors themselves: these from time to time inhabit and define the scene with choral actions, the proscenium and the boxes with the clownish interruptions of Democritus, the auditorium with the orchestra and the actions in the audience. Longhi comments: «About the space I have to say that I was electrified by the first notation in Alejandro’s script: it describes a large white and empty space, which in the first initial sequence is illuminated in different ways, as if a day were passing. It struck me that he did not know that the stage of the Storichi in Modena is white. When I read that first stage direction and thought of it inside the Storchi, I said to myself: there is almost nothing to do here, you just have to live in that space». In addition to the structure of the scene, already white, the possibility in the Storchi theatre to open the window door overlooking the gardens in the back creates a dialectic between inside and outside, between nature and artifice, between reality and fantasy. The Storchi stage is already a semantic space and full of possibilities. It was enough to simply create the two doors and place the table on stage, the elements of which the script provided by Tantanian speaks. Compared to the most recent productions and the best known works I’ve done, it’s definitely a different way of using space. But I had already worked in this direction in lesser-known shows, such as Koltés’ In the Solitude of the Cotton Fields and in the Natural Stories of Sanguineti. In this case, the aesthetic need coincided with the need to work in a Covid regime.»

“Once upon a time there was a world, once there was noise out there…” reads the text. What about today? Today, on that stage, there are few white pieces of furniture, a window (really) open onto the green of the trees, but immediately closed. Seeing the actors with masks on their faces in a theatrical show could have reversed things, with the story of something different from today’s world. Instead the show shows precisely the reality in which we live, this particular historical moment. The theme of the pandemic is the background; it leaks in everywhere, as much as in the themes underlying the text, as in the many solutions adopted in the staging of the show. The pandemic, as has been said, was the starting point of the dramaturgy, the production and the project more generally, created to reflect on what is happening. Longhi says: «I didn’t want for ERT a 2020-21 season made up of covid document dramas. However, the experience we are undergoing has led us to redefine our concerns, our fears, our expectations. I was interested in returning to and presenting at the theatre a particular feature: the one that makes it a mirror of the reality that surrounds us. Not an ascetic mirror, but a deforming one, as Turner would have said, a mirror that enlarges or shrinks, a “disguise,” as Sanguineti would have said.»

In fact, in the show the pandemic is everywhere and at the same time it is nowhere. There are masks on stage… sanitizing gels, but it’s all deliberately between the lines. Spiritism and materialism in dialogue with each other are at the heart of it. Longhi explains: «In this work there is, at the end of the day, a reflection on the power of mystery and the power of fantasy. I don’t really like the mystery category, but this time I was pleased to engage with the dimension of mystery. I feel like I have a pretty neo-Enlightenment approach, I had a jolt when I found myself confronting these materials. And yet, working, I found it a consonance and a profound challenge. Even the reflection on fantasy, inherent in the text, is a fundamental component of the scientific gaze, because it activates a kind of dialectic in which neo-Enlightenment lucidity cannot but enter into a dialogue with evasion from procedural clarity.»

The Weight of the World in Things. Photo: Francesca Cappi. Courtesy of the ERT – Emilia Romagna Teatro Press Office.

The Weight of the World in Things seems to make real – in the text and in the staging – the profound meaning of one of the central observations made by the protagonist of Berlin Alexanderplatz, the best known of Alfred Döblin’s novels: “Life does not begin with good words or good intentions, you start by knowing and understanding it and with the right companion.” The show turns out to be a close reflection on Döblin’s overall poetics and references to the present that can be grasped in it. The key to reading offered to viewers seems to lie in the words of Marina Cvetaeva, words that give the title to the show and that are posed as an introduction to the text itself: “I have never learned to live: I do not live in the present, I am never there. I feel in harmony with all the people who cannot be a presence in the world. But I can feel its weight: the weight of the world in things, its weight in the mountains, even the weight of time on a budding child that no one feels.” It is no coincidence that, in stressing their importance, these words are repeated in the fifth and seventeenth scenes, reminding us that, if we want to find the world again, we must first recognize the naturalness of the ‘weight’ which is manifested in all things.

I would like to close this short article with the words of Tantanian and Longhi, taken from the notes to the show. These words that summarize the profound meaning of their project and of the dramatic moment that we are all experiencing: «As a result of an improvised sneeze of nature in its lowest manifestations (its height a microscopic virus, rigorously crowned, however – delivered to us, as in the most anguished tales of terror, from a sinister and fluttering lackey in bat livery), for some months our world seems to have come off its hinges. After decades of learned and sharp anatomies of modernity and its myths, the “global risk” has finally – and suddenly – revealed itself here and now […]. In the clamor of this “grandiose drama” in which day after day hot iron marks our flesh, what space is left for useless theatre – if not that of tracing fleeting and hypothetical maps of our Hamletic “bad dreams” in order to try to find a possible (although very precarious and, not already open, but wide open) order in reality, telling stories? […] The Weight of the World in Things is also and above all a theatre feast, a reflection on the power and function of the imagination (mimetic and otherwise) in relating to reality, as it is. On becoming a community. On being suspended, as in the theatre, as in life. Together, once again, summoned here, waiting for all this to finally become something else, reunited, determined, fatal, heated, laggard, fearful, so courageous, so united, so separated, so worried and so thoughtless, sick, healthy, alive, dead, together, once again. Come! All of you are welcome! Once upon a time (perhaps)… ».

Daniele Vianello, vice-president EASTAP (European Association for the Study of Theatre and Performance), is Professor at the University of Calabria (UniCal), where he teaches Performance History, Drama, and Staging Technique and Theory. He has also taught at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” (2002-2008) and at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice (2015-2016). He is member of the editorial board of European Journal of Theatre and Performance, contributing editor and member of the advisory board of European Stages, Olhares, Biblioteca Teatrale, Rivista di letteratura teatrale, among others. His publications, centered mainly on Renaissance and contemporary theatre, include L’arte del buffone (Bulzoni, 2005) and Commedia dell’Arte in Context (eds. Balme, Vescovo, Vianello, Cambridge University Press, 2018). He worked for several years with the Teatro di Roma (Union des Teatres de l’Europe), where he assisted Italian and foreign stage directors (including such figures as Eimuntas Nekrošius).

[1] A. Tantanian, Il peso del mondo nelle cose, Luca Sossella Editore, 2020.

[2] Claudio Longhi has directed shows for the major national theatrical institutions. Among his productions we must mention at least Arturo Ui by Brecht (with a very good Umberto Orsini as the protagonist), the Classe operaia va in paradiso, from the film by Elio Petri as adapted by Paolo di Paolo, La commedia della vanità by Elias Canetti , and most recently, The Weight of the World in Things of Alejandro Tantanian. For further information on Longhi’s artistic biography, see my essay entitled ”The third season of the ‘Piccolo’ – Theatre of Europe, under the direction of Claudio Longhi” in this issue of ES.

[3] As a playwright, Alejandro Tantanian has been awarded in Brazil, Uruguay, France, Spain, Belgium, Austria and Germany. His plays are translated into Portuguese, English, French and German. His directing has been presented in numerous international theatre festivals, receiving numerous awards. He was part of the collective of authors “Caraja-ji” (starting a fruitful collaboration with Daniel Veronese, one of the key figures of the theatre of Buenos Aires in the post-dictatorship period) and of “El Periférico de Objetos” – a “paradigmatic” independent group of the Argentine experimental theatre (founded with Rafael Spregelburd and Mónica Duarte). During his three years at the helm of TNA, he radically changed the face of the Cervantes in Buenos Aires, imprinting a new and easily recognizable aesthetic, andgiving space to plays by both established and emerging authors such as Rafael Spregelburd, Mariano Tenconi Blanco, Emilio García Wehbi.

[4] A. Döblin, Fiaba del Materialismo, Ibis, 1994 (original title Märchen vom Materialismus).

[5] A. Döblin, Traffici con l’aldilà, Adelphi, 1997 (original title Reiseverkehr mit dem Jenseits).

[6] I was authorized by Claudio Longhi to publish the interview, carried out on November 15, 2020, by inserting parts of his reflections in «quotation marks.»

[7] See Daniele Vianello, “Gombrowicz’s and Ronconi’s Pornography without Scandal, the Novel Effect: Mimesis and Diegesis in Scene,” in European Stages, IV, 1, 2015, pp. 1-11; Daniele Vianello, “Teatro e romanzo…,” in Biblioteca Teatrale, 113-114, gennaio-giugno 2015, pp. 93-108.

European Stages, vol. 15, no. 1 (Fall 2020)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Philip Wiles, Assistant Managing Editor

Esther Neff, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 74th Avignon ‘Festival,’ October 23-29: Desire and Death by Tony Haouam

- Looking Back With Delight: To the 28th Edition of the International Theatre Festival in Pilsen, the Czech Republic by Kalina Stefanova

- The Third Season of the “Piccolo Teatro di Milano” – Theatre of Europe, Under the New Direction of Claudio Longhi by Daniele Vianello

- The Weight of the World in Things by Longhi and Tantanian by Daniele Vianello

- World Without People by Ivan Medenica

- Dark Times as Long Nights Fade: Theatre in Iceland, Winter 2020 by Steve Earnest

- An Overview of Theatre During the Pandemic in Turkey by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Frankfurt by Marvin Carlson

- Blood Wedding Receives an Irish-Gypsy Makeover at the Young Vic by María Bastianes

- The Artist is, Finally, Present: Marina Abramović, The Cleaner retrospective exhibition, Belgrade 2019-2020 by Ksenija Radulović

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2020