Swiss-speaking Germany is sometimes overlooked in considerations of the contemporary Germany stage, but the frequent appearance of Swiss productions in the annual Berlin Theatertreffen is evidence of the continuing importance of the theatres of Basel, Bern, and especially Zurich. Two Swiss productions were included in the ten “most remarkable” productions in both of the most recent offerings of this annual festival.

A week in Switzerland in the spring of 2017 gave me the opportunity to experience more of this thriving theatre culture, seeing three productions at the country’s leading theatre, the Zurich Schauspielhaus, and one at the Basel Theatre, a Three Sisters that was also featured in this year’s Theatertreffen in Berlin. The first work I attended at the Schauspielhaus was Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, directed by Alize Zandwijk of the Netherlands. Zandwijk just stepped down this year as artistic director of the Ro Theater in Rotterdam, after heading it since 2006 and directing there since 1998. During those years she also worked as guest director at a number of leading German theatres, including the Thalia Theater in Hamburg, the Deutsches Theatre in Berlin and Theater Bremen. She has been particularly committed to plays dealing with life in the lower classes, beginning, significantly, with her first major success, Gorki’s The Lower Depths, in 1991, which was invited to the Edinburgh Festival and the Vienna Festwochen.

Designer Thomas Rupert has worked regularly with Zandwijk since 1998. His striking design for this production provided one of the most ingenious solutions I have ever encountered to the major design challenge of the play. This is that most of the play takes place in the Ekdal dwelling, a humble interior, although presumably a spacious and rather unconventional one, whereas the opening act alone takes place in the totally contrasting world of the Werle mansion, challenging the designer to create a rich and elaborate interior that is utilized only for what is essentially a prologue.

Rupert’s innovative solution to this challenge is to place the opening act in a kind of visual void.

When the play begins, the stage is totally filled with stage smoke. In the rear wall, two bright lights facing the audience send their beams through the fog, but at first reveal nothing. A strange, disembodied music, perhaps from a bass viol, reverberates through the mists. Slowly we become dimly aware of movement in the mist, and then of running or dancing figures passing in silhouette before the illuminated doors. The music becomes suggestive of a rather grotesque dance, and as a group of silhouettes passes the door in a kind of conga line we are startled to see that one of them appears to be a bear!

Eventually the doors close and different characters emerge downstage out of the still thick fog. We realize that we have seen dancing at Old Werle’s costume party, with himself in a bear suit, the head of which he has now removed for his conversations with the others. Only when Old Werle (Hans Kremer) began to rub his eyes did it occur to me that this striking visual effect of the opening act was probably inspired by the foggy vision of Werle and Hedvig and which is a central metaphor in the play. Later, when we go to the attic, Hedvig (Maria Rosa Tietjen) appears as visually challenged as I have ever seen her played, wandering almost obsessively around the walls of the large space, running her hands along their surfaces for spatial assurance.

Zandwijk, The Wild Duck. Photo: Matthias Horn.

When the mists dissipate we see that large space, the Ekdal attic, a huge, largely empty room done by Rupert somewhat reminiscent of a setting by Anna Viebrock. A large boxy structure like an internal chimney wanders up the left wall, reinforced by large, wooden supporting beams, while the right wall has a large assortment of stuffed animal trophies. Some are the standard heads, but others are the whole front parts of the bodies of deer and other creatures, appearing almost as if they are in the process of leaping through the wall. Strangely enough, there is no door into the garret domain of the wild duck. Its attic is superimposed mentally upon the room we see, so that it is not at all clear whether this strange space even actually exists. Occasionally, for example, Hjalmar will apparently scatter grain across the floor for imaginary chickens, and Hedvig shoots the pistol downstage, apparently within the room. There is, however, a real box with an apparently real duck in it that Hedwig fiercely protects.

At the rear of the stage is a small platform reached by a ladder, which serves as the room of Old Ekdal (Siggi Schwientek). In the middle of the wall a small platform contains the musical instruments, mostly strings with a few wind pieces, which have provided a rather sinister, non-lyric background since the opening and continue to do so throughout the evening. They are all played by a single musician, Maartje Teussink, who created the score. Like the designer and the dramaturg, Karoline Trachte, she came with the director from the Ro Theatre, while the actors are all from the regular Zurich ensemble.

The ethereal Hedvig of Marie Rosa Tietjen, a pre-Raphaelite figure with long dark hair and a flowing white dress, makes the most powerful impression of the evening, although she seems to be drifting in a world apart from that of the other characters. The key roles of Hjalmar and Gregers are performed by Christian Baumbach and Milian Zerzawy. Hjalmar is not so comic as he is often played, nor Gregors so neurotic, but both present convincing images of confused and troubled figures attempting to make sense of a world slipping away from their control. Ludwig Boettger, a long-time veteran of the company, presents a similarly insecure Relling, but I missed his companion Molvik, which this production somewhat surprisingly decided to omit. The servants and party guests from the first act I can do without, but Molvick seems to me to add a very important note to the later acts.

Herbert Fritsch, Grimmige Märchen. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf.

The next production I saw at the Zurich Schauspielhaus was a new piece by one of my favorite contemporary German directors, the imaginative and innovative Herbert Fritsch, whose exuberant physical farce spectacles have been highlights of the Berlin Theatertreffen now for a number of years. Some of these are original works while others are pre-existing literary or dramatic pieces filtered through the Fritsch theatrical consciousness, which is as distinctive and visually fascinating as that of Robert Wilson.

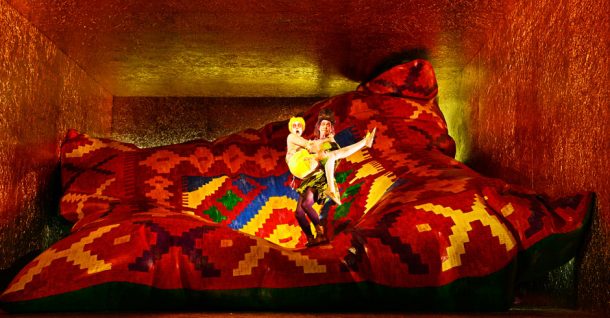

As is the case with Wilson, there is often a distinctly grotesque edge to Fritsch’s visualizations, and this is particularly well suited to this most recent work, based on the Grimm fairy tales. Actually, the punning title Grimmige Märchen works better in English than in German (where it means something closer to “grimy fairy tales”), which is appropriate since in German the tales are better known the title their collectors, the Grimm brothers, originally gave them: Kinder- udn Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). Fritsch, as usual, has designed his own setting, which, as is often the case, is a much larger than life household object, in this case a lumpy decorative pillow, which covers most of the stage and provides a variety of irregular performance areas for the actors.

When the play begins eight actors in grotesque costume, makeup and wigs, some fairly recognizable—King Thrushbeard, Hansel, and Red Ridinghood—and others only vaguely suggesting characters from the tales, are frozen in positions around the stage. They soon move into frantic activity, bouncing off the walls, each other, and a trampoline hidden in the center of the giant pillow, forming unstable human chains and bodily clusters, and throwing at us bits and pieces of various tales, some familiar but most more obscure and almost all dealing with murder, savagery, famine, torture, and tales of the grave. As is customary in Fritsch’s works, scenes of collective but highly orchestrated mayhem alternate with brilliant solo performances which are marvels of comic imagination and physical virtuosity. Florian Anderer, who has appeared in many of Fritsch’s works, is at his comic best here, as a hunchback fool in a top hat and green jerkin (costumes by Victoria Behr) playing countless variations on the physical challenge of performing at breakneck speech on this bizarre setting. Markus Scheumann as King Thrushbeard appropriates Cinderella’s show and turns it into a mobile phone upon which he performs an extended routine with almost no actual words which keeps the audience convulsed in laughter near the end of the evening. The thin line between inspired slapstick and the most threatening and disturbing human situations is constantly explored in this brilliant evening, and its continual surprise and inventiveness is truly overwhelming.

Henkel, Onkel Wanja. Photo: Matthias Horn.

My third evening in Zurich offered a sharp contrast in tone—a moving interpretation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, directed by Karin Henkel, one of Germany’s leading directors, whose work was presented at the Berlin Theatertreffen every year between 2011 and 2015. The evening begins with the pathetic figure of Siggi Schwientek as Vanya standing downstage center, the picture of hopeless melancholy, so perfect as to touch on the comic. In one hand is a revolver, in the other a vodka bottle. Schwientek has been at the Schauspielhaus since 2000 and is a leading member of the company, although Zurich is outside my usual theatre circuit and this visit was my first encounter with his work. I found him excellent, but not outstanding, as the decaying old Ekdal in the Wild Duck, but his bravura performance as Uncle Vanya quite dazzled me. His drooping features and enormous melancholy eyes are so striking and memorable that he might almost be wearing a mask depicting hopelessness, and Henkel often placed him looking vacantly out into the audience, reinforcing the mood of quiet despair. His thinning gray hair, straggly beard, hanging shoulders, ratty and faded flowed sweater and warn jeans all contribute to this depressing image.

Although Schwientek stands out, the company around him creates a striking ensemble of frustration and despair, with Carolin Conrad as a weighted-down Sonja, Gottfried Breitfuss as an angry but uncomprehending professor, and Markus Schumann as a bewildered Astrov. Only Lena Schwarz as the Professor’s trophy wife flits apparently unaffected above this crushing world.

The visual world surrounding these actors adds powerfully to the sense of hopelessness and despair. The sad and faded 1950’s costumes by Aino Laberenz add an important touch, but most effective is the physical stage itself. At the rear is a wall upon which from time to time is projected an image of a hypnotic ride into a seemingly endless tunnel. As the evening goes on, we become aware that this wall is actually composed of large window-pane like sheets of ice, which gradually melt away as the evening progresses, leaving only empty frames at the end. The steady dripping away of the melting ice, with the occasional crash of a larger piece slipping down punctuates the evening with a constant feeling of something slipping away, and the collected water from the wall gradually builds up on the stage, with the actors eventually moving through ankle deep water, of which they are seemingly unaware.

As the end of the play, Carolin Conrad delivers Sonja’s upbeat speech with an almost hysterical intensity, but it is Schwientek’s opening figure of despair, weighing the relative advantages of the revolver and the vodka, and the slowing rising water, suggesting that all will eventually be washed away, that remain the lasting impressions of this powerful production.

Simon Stone, Drei Schwestern. Photo: Sandra Then.

I had high hopes for the Simon Stone production of Three Sisters, which I attended at its home in Theater Basel. The work had received very enthusiastic reviews from the German press, and had been selected to open the prestigious Berlin Theatertreffen the month after I saw it in Basel. In fact, I found it in many ways the most disappointing evening I spent in Switzerland, for many of the same reasons that troubled Lily Kelting, whose more extensive review of it with the Theatertreffen appears elsewhere in this issue. To begin with, the critical reception of the production made seats hard to obtain and I had to sit in the balcony, which meant that since the setting was a free-standing, glass-walled multi-room house complete with an opaque roof, the upper part or more of any actor disappeared whenever they moved into the interior of the rooms, which of course happened frequently. Less irritating, but equally careless, was the use of snow in the second act. It made a nice realistic effect—the entire production playing with such effects, but as it was not real snow, it remained on the roof for the entire third act, which takes place the following summer, so that balcony spectators, deprived of a view of much of the action, were instead treated to a view of a totally unsuitable snow-covered roof in mid-summer.

Director Stone has radically modified the play, never, in my opinion, for the good. The story has been relocated to contemporary times and the language salted with current banalities and explicatives. This would not be fatal, perhaps, but what is fatal was the decision to covert the Prozorov family home into a kind of summer cottage, visited by the family only on holidays and vacations. The sense of entrapment so crucial to Chekhov’s play is totally dissipated as the characters wander freely into the offstage areas where clearly their real lives are taking place, gathering only now and then in the elaborate glass box. Each act is based around some activity which keeps everyone busy, and creates a sense of action which has in fact nothing to do with the text—the preparations for an elaborate summer brunch, or decorating the house for Christmas, or finally, carrying everything offstage to clear out the premises for the season or for sale (a final sequence that somewhat recalls The Cherry Orchard, but which has nothing whatever to do with Three Sisters). No one loves radical reworking of classic texts more than I do, but only when such reworking either opens new dimensions of the original or when the reworking allows the play to make significant social or theatrical points far from those of the original. Alas, this noisy and banal production does neither.

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is a theatrical autobiography, 10,000 Nights, University of Michigan, 2017.

European Stages, vol. 10, no. 1 (Fall 2017)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 2017 Avignon Festival: July 6 – 26, Witnessing Loss, Displacement, and Tears by Philippa Wehle

- A Reminder About Catharsis: Oedipus Rex by Rimas Tuminas, A Co-Production of the Vakhtangov Theatre and the National Theatre of Greece by Dmitry Trubochkin

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2017 in Brussels by Manuel Garcia Martinez

- A Female Psychodrama as Kitchen Sink Drama: Long Live Regina! in Budapest by Gabriella Schuller

- Madrid’s Theatre Takes Inspiration from the Greeks by Maria Delgado

- A (Self)Ironic Portrait of the Artist as a Present-Day Man by Maria Zărnescu

- Throw The Baby Away With the Bath Water?: Lila, The Child Monster of The B*easts by Shastri Akella

- Report from Switzerland by Marvin Carlson

- A Cruel Theatricality: An Essay on Kjersti Horn’s Staging of the Kaos er Nabo Til Gud (Chaos is the Neighbour of God) by Eylem Ejder

- Szabolcs Hajdu & the Theatre of Midlife Crisis: Self-Ironic Auto-Bio Aesthetics on Hungarian Stages by Herczog Noémi

- Love Will Tear Us Apart (Again): Katie Mitchell Directs Genet’s Maids by Tom Cornford

- 24th Edition of Sibiu International Theatre Festival: Spectacular and Memorable by Emiliya Ilieva

- Almagro International Theatre Festival: Blending the Local, the National and the International by Maria Delgado

- Jess Thom’s Not I & the Accessibility of Silence by Zoe Rose Kriegler-Wenk

- Theatertreffen 2017: Days of Loops and Fog by Lily Kelting

- War Remembered Onstage at Reims Stages Europe: Festival Report by Dominic Glynn

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016