By Marvin Carlson

Frankfurt, though the birthplace of Goethe, and the home of the Theater am Turm, which during the 1960s was among the leading experimental theatres in Germany, does not have much of a reputation in the current German theatre, although, like any German city of any respectable size, it has an active theatre scene and a wide range of well supported venues. Normally I have visited the city only on my way to somewhere else, but I made for the first time a special trip in January of 2020, attracted by an unusual, indeed unique theatrical offering. The city’s main theatre, the Frankfurt Schauspiel, offered in its repertoire Ibsen’s two epic dramas Brand and Peer Gynt. The challenges offered by these monumental works make stagings of either uncommon, and no theatre has ever mounted the two of them at the same time.

The motivation for this unique event was the annual Frankfurt Book Fair, the largest and most important such gathering in the world. For many years the fair has selected the literature of a particular country to emphasize, and that chosen for 2019 was Norway. In honor of the occasion, and with the financial aid of the Norwegian government, the Frankfurt State Theatre opened its Peer Gynt on May 23 and Brand on October 12. Since the Frankfurt Schauspiel follows the usual German repertory system, rotating the plays in its active repertoire, a theatre goer visiting the city for several days in late 2019 or early 2020, as I did, could see both productions in close proximity.

The first thing that must be said is that while presenting these two monumental works in repertory offers a very special opportunity both for Ibsen lovers like myself and for the general theatre-going public to experience something of the scope of Ibsen’s dramatic and poetic imagination, it does not use this almost unique opportunity to allow the works to reflect theatrically upon one another. To be honest, I thought this a missed opportunity. Both directors are leaders in the German theatre and both productions were ambitious and even praiseworthy, but the only connection between them had to be the work of the spectator’s imagination. I could not help wondering what the result would have been if a single director, one of these two or any one of a number of other leading directors of the contemporary Germany theatre, had undertaken to direct both shows (a number of such directors have taken on no less ambitious projects, such as both parts of Faust) and in some manner or other put them into conversation.

Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, directed by Andreas Kriegenberg. Photo: Frankfurt Schauspiel.

However, I must report on what was done, not what I might have wanted, and both productions in fact had much to offer. The first I saw was Peer Gynt, presented by one of my favorite German directors, Andreas Kriegenberg. Kreigenberg often serves as his own designer, and often utilizes ingenious and highly technological means in his productions. He has however also worked with the well known Austrian designer Harald Thor, and as is often the case with Kriegenberg productions, the design, for good or ill, dominates the production. The production opens with the stage presenting a rather sterile but highly realistic hospital room, all in stark white, with a single bed, surrounded by hospital fittings, to the left. At the center rear an opening gives onto featureless white corridor. A figure, whom we later learn in Peer, lies in a hospital gown on the bed with his back to us. Other figures in the room include several nurses and doctors, all in white and going about their business in a rather mechanical manner, and three figures in darker, more conventional clothing, whom we learn are Peer’s mother and father (Katharina Linder and Sebastian Reiß) and Solveig (Sarah Grunert). Through mimed action and a small amount of dialogue (not in Ibsen), a frame situation is established. Peer is a long-term (perhaps permanent) catatonic patient in a combination hospital/asylum, apparently regularly visited by his wife and parents. Solveig in particularly seems well acquainted with the nurses, and chats casually with them over coffee.

Although this basically realistic situation is now and then disturbed, subtly by the rather mechanical movements of the nurses, and more strikingly when one of the presumed doctors goes out of control and is revealed as a patient in medical garb, the opening sequence as a whole clearly establishes the premise of the production—that the entire action of Ibsen’s play is taking place in the mind of the catatonic patient we see on the bed. Having just a few months earlier seen the Jonathan Kent Peer at the National Theatre in London, I was struck both by the similar directoral interpretations of Peer’s advantures, and also by the much greater development of this interpretation (as I would expect) in Germany. In London, Kent’s Peer (James McArdle) is rendered unconscious by running into rather incongruous door in the mountains, and during his subsequent encounters with the trolls, a body double remains lying onstage with his back to the audience while McArdle, apparently dreaming, continues the troll sequence, even eventually returning to shake the unconscious “Peer” in a futile attempt to escape the dream.

Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, directed by Andreas Kriegenberg. Photo: Frankfurt Schauspiel.

The concept of the unconscious unmoving Peer remaining in his hospital bed while the active Peer (Max Simonischek) pursues the actions of the play is essentially the same in Frankfurt, except that Peer is already in a coma when the production begins, and never emerges from it, while the McArdle awakens after the Boyg scene as performs the rest of the play in apparent consciousness.

The transition from the hospital sequence into Ibsen’s play proper is managed by a technological device typical of Kriegenberg in its physical spectacle. The actors onstage freeze in position and the inert figure of Peer rises and goes into the upstage hall where he pulls down a folding ladder from a hitherto unseen ceiling trap and climbs up. As he climbs, the entire stage slowly sinks out of sights and he emerges into a totally different, a much larger and far less realistic world. Now only dimly lit, faintly suggesting a primeval forest. The center of the stage is a bed of dark material—earth, mud. mulch, perhaps rotting organic matter, through which Peer drawls as he begins the opening lines of the play. Other indistinct figures similar crawl through this space and surround them, are dozens of huge greenish-brown boards, perhaps a foot wide and perhaps 30 feet long, standing on one end and stretching upward at different angles, like the contents of an ill-tended lumberyard. The impression was rather like that of an dense, abstract forest composed only of trunks, or of a grassy lawn with Peer shrunk to insect size. Although the figure of Peer from time to time (as after the Boyg scene) goes back down the ladder and into his hospital bed, the production clearly assumes that on the realistic level he never stirs from the bed and Ibsen’s picaresque adventures are all within his dreaming mind. Thus, unlike most Peers I have seen, Simonischek plays Peer throughout as roughly the same age, a man in full maturity (he is in any case a large and imposing figure), clearly older than the usual Peer of the first acts and younger than that of the homecoming.

In the course of the evening, individual planks were used by the actors to create different playing spaces, but the physical configuration of this dream world remained the same. In many scenes vague figures—trolls, Arabic maidens, and other unidentifiable shapes would move upstage among and behind these boards, observing Peer or going about their own mysterious business. Aside from the planks, scenery was minimal, but from time to time actors would use individual planks to suggest other setting. Usually with the aid of hooks and cables dropped from the ceiling. So Peer and the Troll King’s daughter swung back and forth at opposite ends of a plank supported like a swing by two cables, and the four merchants in Morocco each balanced on his own individual plank swing. Two plank swings supported the head and foot of Aase’s death-bed-sledge and a number of planks were lashed together to create the ship that returns Peer to Norway.

Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, directed by Andreas Kriegenberg. Photo: Frankfurt Schauspiel.

From time to time, the hospital asylum setting would reemerge from its depths and as the play went on the two worlds bled into each other. The earth and mud that Peer tracked in from above puzzled the interns in the otherwise spotless hospital room, and figures would wander into this room that represented both other patients in this institution and parts of Peer’s alternate universe. The blending became most complete in the middle of the play when the hospital room itself served as the setting for Cairo insane asylum, with Peer as one of the patients.

The production ends, as it began, in the hospital room. The Button Molder (Christoph Pütthoff) and the other characters of Peer’s fantasy universe are left behind on the upper level as the faithful Solveig, by Peer’s hospital bed, helps his large but feeble body into a wheel chair, and slowly rolls him up to the center opening and out of sight through the hospital corridor.

Ibsen’s Brand, directed by Roger Vontobel. Photo: Frankfurt Schauspiel.

The Brand, which I saw three nights later in the same theatre, was a very different experience. Again both the director, Roger Vontobel, and the designer, Olaf Altman, are leading figures in the contemporary German theatre. Although the two, working together and with other artists, have presented a wage range of works, modern and classic, in a wide variety of styles, both have a strong interest in massive minimalistic settings of platforms, stairs and simple geometrical shapes, and clearly the stark contours of Ibsen’s Brand suited well this orientation. Altman’s setting was composed entirely of simple shapes, somewhat reminiscent of Stephane Brauschweig’s monumental/minimalist production of this play in Stuttgart in 2005. Although one had the impression of neutral monumental shapes—a huge seeping curve forming a partial framing arch to the left, a flat neutral area running across the downstage area, a receding platform, slightly titled, leading upward toward the rear of the stage to the right, and an unseen ramp or stairs that allowed actors to come up into the acting area from behind the left side of this large platform. Little else could be seen, and even these elements were shrouded in think moving clouds of smoke throughout the evening, so that characters would often make entrances and exits simply by disappearing into the clouds. The area represented seemed to be the fells, that mysterious setting of one of Ibsen’s most famous poems high above most habitation but with the real mountain peaks still towering above. The consistent use of the area to the left of the tilted platform by characters coming from or going to the town, their heads appearing first as they ascended to the stage, strongly reinforced this image.

Although the drifting clouds and changing lighting (very often characters appear as silhouettes) seems to keep the visual field in constant motion, there is only one major shift in the scenic configuration, making it all the more striking. As Brand ascends into the ace church near the end, the huge tilted platform slowly rises, so that it is only with great difficulty that he is able to climb almost to its top, where he lies with his arms spread out as if crucified. The image is all the more striking in that the surface of the platform, which up until then seemed a flat cold grey is now lighted in such a way as to reveal itself in dazzling metallic gold, with Brand pinned against it like a small insect on display. After this stunning moment, the actual play ending, with Brand sliding down to deliver his final lines on the main stage, seemed anticlimactic, especially in that Ibsen’s famous and much debated final “deus caritas” line is cut and the play end with Brand’s final question, and a crashing sound like a shot, leaving open the possibility that he has been killed by Gerd, or even committed suicide—fascinating possibilities, but surely not what Ibsen originally had in mind.

Ibsen’s Brand, directed by Roger Vontobel. Photo: Frankfurt Schauspiel.

The performance, though it runs for nearly three hours, is still much cut, containing only about a third of the original text. Peer Gynt is cut as well, of course, but less radically—it runs over four hours. The Brand translation is a new one, especially commissioned for this production, from one of Germany’s leading translators, Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel, who has previous translated A Doll House, Hedda Gabler, The Master Builder and John Gabriel Borkmann. The Peer Gynt on the other hand, uses the text created by Both Strauss and Peter Stein for Stein’ 1971 two part production of the play in Berlin, widely considered the most important modern production of the play. The Stein translation is in poetry, that of Schmidt-Henkel in prose, and to my mind was far more successful in catching something of the flavor of the original.

Heiko Raulin, in his stiff black, floor length clerical gown (costumes by Ellen Hofmann) did not seem to me ever to reach the fanatic power of Ibsen’s protagonist. He seemed rather to very successfully set off the play’s two major women, the angelic Anges (Jana Schulz) and the demonic Gerd (Katharina Bech), both of whom are given much more prominence in this production than is normally the case. Gerd in particular hovers over the production like a bird of prey, whom her posture, movements and cries seem literally to evoke. Often her voice or her twisted shape can be discerned in the mists, not infrequently seeming to have a direct physical impact on Brand. Less prominent but also profiting from a contrast to the rather monochromatic Brand is Isaak Dentier as the district administrator, down-to-hearth, venial, and surprisingly engaging. The electronic musical score, created and performed by Keith O’Brian underscores and considerably enhances the entire production.

I had two evenings free between these productions at the Schauspiel, and the city offered many possibilities—classic and contemporary work, cabaret, musicals, even magic and circus. Being a devotee of Stephen Sondheim, I could not resist Sweeny Todd, at the English theatre of Frankfurt, continental Europe’s largest English-speaking theatre, located in elegant quarters on the ground floor of a commercial skyscraper, the Galileo building, on the same large square as the Schauspiel.

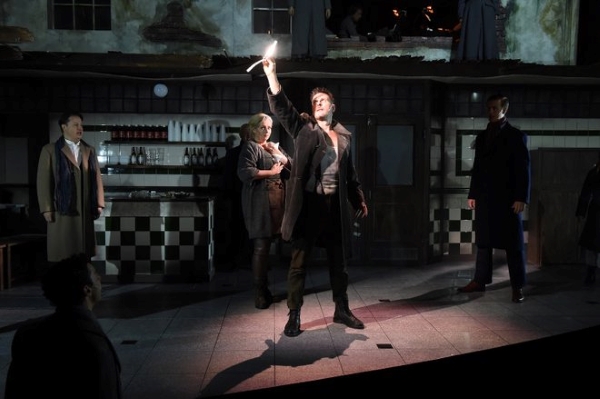

Sweeney Todd, directed by Derek Anderson. Photo: Martin Kaufhold.

Popular as the play is in the U.S. and England, it is almost unknown in Germany, and the overflow audience was clearly both delighted and shocked by the play’s bloody excesses. Far from minimalizing this aspect of the show, director Derek Anderson emphasized it. Spurts of blood shot out into the audience from the slit throats of Sweeney’s victims, some of the patrons of Mrs. Lovett’s shop carried their meat pies out into the house to offer bites to audience members, and most strikingly, about a dozen audience members were placed in a “Splash zone” on stage wearing protective ponchos, and closely involved in the action physically if not dramatically. Seated together in an alcove on the left of the stage, they were only a few feet from the action. When Mrs. Lovett (Samantha Ivey) is throwing herself into the preparation of her meat pies, they are showed with flour, and later with shaving lotion as Signor Pirelli (Matt Bateman) whips it up preparing for his shaving duel with Todd .

Director Anderson brought this intimate interpretation from a successful award-winning revival at the newly opened Twickenham Theatre in London in 2014. The most praised performer in that production, Sarah Ingram as Mrs. Lovett, was in fact scheduled to revive the role in Frankfurt, but her voice failed on opening night, and she was replaced by her understudy Samantha Ivey, who the evening I saw it provided an excellent companion, physically and vocally to Stephen John Davis, boasting a distinguished career on the London musical stage. Indeed the entire cast came from the London theatre, and created a performance which would have doubtless been well received in the British capital as well.

Stephen John Davies and Samantha Ivey. Sweeney Todd, directed by Derek Anderson. English Theatre Frankfurt. Photo: Martin Kaufhold.

Anderson brought with him to Frankfurt his London set designer, Rachel Stone and costume designer Olivia Ward, who apparently recreated something close to the physical look of the London production. For most of the evening the entire stage serves as the pie shop. Up stage center is an opening which usually contains the door opening into the shop. There is a higher level which appears to be an unfurnished second floor/ Its main visual feature is a large multi-paned window, mostly broken away so that we can see behind it the two-man orchestra, piano and percussion. Although characters from time to time move across this space it never is clearly defined and it notably does NOT serve, as in most productions, of the location of the new barber shop and its infamous chair. The shop is instead located on the right hand side of the main stage, with Mrs. Lovett’s pie shop to the left. Thus, when Sweeney has killed his victims, then do not drop down through a trap as in most productions, but their chair slides backward into an opening door in the wall behind them, and quickly returns empty for the next patron. This worked quite satisfactorily, though given the fact that the stage had a second floor I rather missed the added if admittedly more complex upstairs version. David Pendlebury, another seasoned veteran of the London musical stage, was excellent as the villainous Judge Turpin, ably seconded by Nathan Elwick as Beadle Bamford. Matthew Facchino and Aliza Vakli were engaging young lovers and Tobias was winningly portrayed by a young woman, Lucy Warway, from the Guildford School of Acting. The performance was sold-out and clearly the audience enjoyed what was for most their first Sondheim. The woman seated next to me asked if Sondheim was a known name in the U.S. and was pleased to be informed that he was.

Without a single actual German play to show for my Frankfurt visit, I selected for my fourth evening a particularly fitting one, Faust, the greatest work by Frankfurt’s greatest author. Indeed I prepared for the evening by visiting for the first time the fascinating museum which is now housed in Goethe’s restored childhood home in the inner city.

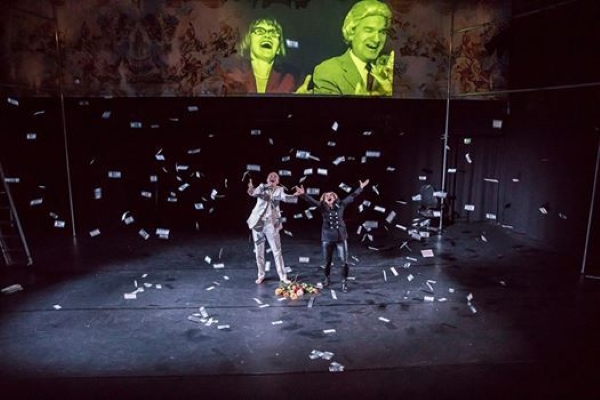

Goethe’s Faust, directed by Reinhard Hinzpeter. Photo: Felix Holland.

I found a staging of Goethe’s work being offered by one of Frankfurt’s leading experimental theatres, the Freie Schauspiel Ensemble Frankfurt, founded in 1984, a loose association of theatre professionals in the city who come together in various combinations to realize their projects, somewhat in the manner of Mabou Mines in New York. Their two-person version of Faust was created in 2016 and has been revived from time to time since. The two current artistic directors of the ensemble, Reinhard Hinzpeter and Bettina Kaminski, are at the heart of this project, he as the director and she as one of the two-person cast. The other is Axel Gottschick, very well known in German films, TV and radio drama in addition to his stage work.

The basic casting of the evening was Gottschick as Faust and Kaminski as Mephistopheles, which roles they maintained, establishing from the beginning an engaging contrast—Gottschick thoughtful, probing and deliberate, Kaminski mercurial, sly, and insinuating. Each plays other, smaller roles throughout the evening, almost never departing from their base characters at the same time. One notable exception is one of their most moving sequences, when they play the ancient couple Philemon and Baucis, the innocent victims of Faust’ imperial vision. The two form almost a single body, sharing a rough-hewn cloak and each with a pair of glasses with one lens blacked out. Few other characters are as clearly defined, except of course for the two leading ones, and I was particularly unconvinced by Kaminski’s Gretchen. Clearly too old for the role, she has decided to play her as a kind of caricature of a naïve young peasant, which I felt diminished the character, the situation, and Faust himself.

Axel Gottschick and Bettina Kaminski in Goethe’s Faust, directed by Reinhard Hinzpeter. Photo: Felix Holland.

Visually, the production was almost as minimalist as the casting. The setting was an essentially empty stage (setting by Gerd Friedrich) with a tall stepladder, occasionally used, to one side, and rolls of barbed wire across the back. As Faust’ world closed in at the end, these coils surrounded the acting area, still littered with the paper money from Faust’s earlier experiments with capitalism, creating a strong and effective stage image. A large screen above the stage, occasionally used for projects of abstract landscapes, fire, or the heads of the Emperor and other dignitaries, was less successful and could, I think, have been omitted.

A minimalist Faust is something of a contradiction in terms, but I found the experiment an engaging one on the whole, and enjoyed an extra benefit from seeing it in close conjunction with Peer Gynt. Although this production, like Brand obviously made not attempt to acknowledge the related Ibsen play currently being performed, the Faust echoes in Peer, of which I had long been at least somewhat aware, added an unexpected extra element to this unique spectatorial experience.

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is a theatrical autobiography, 10,000 Nights, University of Michigan, 2017.

European Stages, vol. 15, no. 1 (Fall 2020)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Philip Wiles, Assistant Managing Editor

Esther Neff, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 74th Avignon ‘Festival,’ October 23-29: Desire and Death by Tony Haouam

- Looking Back With Delight: To the 28th Edition of the International Theatre Festival in Pilsen, the Czech Republic by Kalina Stefanova

- The Third Season of the “Piccolo Teatro di Milano” – Theatre of Europe, Under the New Direction of Claudio Longhi by Daniele Vianello

- The Weight of the World in Things by Longhi and Tantanian by Daniele Vianello

- World Without People by Ivan Medenica

- Dark Times as Long Nights Fade: Theatre in Iceland, Winter 2020 by Steve Earnest

- An Overview of Theatre During the Pandemic in Turkey by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Frankfurt by Marvin Carlson

- Blood Wedding Receives an Irish-Gypsy Makeover at the Young Vic by María Bastianes

- The Artist is, Finally, Present: Marina Abramović, The Cleaner retrospective exhibition, Belgrade 2019-2020 by Ksenija Radulović

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2020