Curated by Christophe Slugmuylner, the Kunstenfestivaldesarts is an exceptional festival devoted to modern art and stage innovation that gathers imaginative productions from around the world, many of them partially produced by the Festival. The 2018 festival took place from May 4 to 26. Contrary to the last two festivals, this year’s program did not include special guests with a few events around them. Unlike previous years, the festival did not have a particular theme or specific area of focus. Still, the choices of the Kunstenfestivaldesarts are often orientated towards productions that explore the limits of genre as well as traditional methods of perception. This means that many of the productions initially provoke puzzlement and wonder as the audience members are faced with things which they have never seen before. Due to their originality, there is currently little to no literature on how to deal with these productions. This article will try to describe some of these innovative productions.

Theatrical Productions

One of the most highly anticipated and successful productions of the Kunstenfestivaldesarts was La reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (The revival: Storie(s) of the theatre) directed by Milo Rau. The title is inspired by the film Histoire(s) du cinéma by Jean-Luc Godard, in which the filmmaker deals with the history of twentieth-century film. With this new production, the Swiss director living in Belgium aims to begin a new cycle of productions about the history of the theatre.

But only part of the production is about the theatre – and not in a very different way from previous productions, in which the innovative aspects always involved a reflection on what the theatre is and how it can help to grasp deep social and political questions. Here the theatre serves as a frame within the story, but also, in a very Brechtian way, as a reflection about how to handle social problems. The main story is based on an actual crime committed in the city of Liège in 2012: the production is very intelligently built up as a play-within-a-play, showing how the production was built, and an investigation of what had really happened. Both the elaboration of the production and the investigation reveal the depressing social atmosphere of a city still deeply affected by the restructuring of the steelworks industry in the 1980s. Like all Milo Rau productions, it involves actors who were somehow involved in the actual events. In this particular instance, Sébastien Foucault has attended the criminal proceedings against the murderers of the young homosexual Ihsane Jarbi; two non-professional actors, a former caretaker of a building, Suzy Cocco and a former storekeeper, Fabien Leenders, are unemployed inhabitants of Liège. Along with the other three actors. Sarah de Bosschere, Johan Leysen, and Tom Adjibi, they have carried out an investigation and spoken with people involved in the events, just as Milo Rau and his actors always do.

The production begins with an actor downstage asking the public, as an actor with fifty years of professional experience, what acting is: he defends realistic acting (delivering a line is like delivering a pizza) and makes a critique of actors who prepare themselves for a long time before the performance (they are playing at being actors), and the directors who shout at actors (the director is playing being the director). After this speech, delivered in an ironic and Brechtian way, the name of the production and those of the actors are projected onto a screen that is above the stage, as if it were a film.

Then the production is divided into five parts, like the five acts of a tragedy. In the first act, the production continues with an audition of three actors. Following a recurrent “mise en abime,” the playgoer-actors are asked about their lives in Liège, and about whether they would be able to perform certain stage actions (to appear naked, to kiss, to beat another person). As in other Milo Rau productions, the actors speak in front of a video camera and their images are displayed in close-up shots on the screen above the stage while they perform. There are very often dissociations between the image on the screen and the image on stage, the filmed image showing moments that have already taken place, or other complementary images. The investigation of the crime seems a pretext to talking about the social atmosphere in the city of Liege (images of which appear on the screen), which seems at times to be the main topic of the play.

The three following parts of the production show the investigations done by the actors to understand the crime and its consequences. The production deals with human relationships, with culpability, shame, and violence. The violence is both physical and psychological, and the acting substantiates the violence described in the story. For example, the aged playgoer-actress and one of the professional actors appear naked on stage (despite saying during the audition that it seemed to her a little bit late at 65 years to appear undressed on stage): they play the murdered young man´s parents at the moment when they find out that their child has been killed, showing the trouble caused by the death and their vulnerability. Another actor explains how, when visiting one of the killers in prison to prepare for the production, he had been surprised by the banality of the man (to whom he compares himself). Then, in the fourth part, entitled a long scene of twenty minutes entitled “The anatomy of the crime” shows the crime itself as it could have really happened, with an actual car being pushed on stage. The young man accepts getting into the car where he is beaten to death for no reason other than the deep frustration of the three killers. Throughout the piece, the realistic acting is deeply enmeshed with detachment techniques: during the scene of the crime, a camera is in front of the car filming close-ups of the faces of the people inside, which are projected onto the screen.

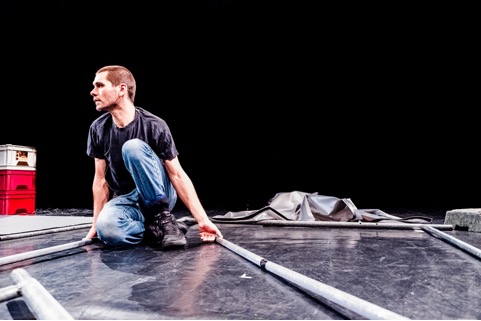

La reprise: Histoire(s) du théâtre (The revival: Storie(s) of the theatre). Photo: Michiel Devijver.

The last part of the production comes back to the theatre, with the partial aim of erasing the impression produced by the violence shown, with a poem by the Polish poet Szymborska, about her preferred final part of a theatrical production: after the end, when all the fictional horrors are undone. Finally an actor, with another meta-theatrical question, alludes to the difficulty of ending a production, repeating the story of an actor who climbs on a chair, puts a chord around his neck and jumps. If somebody in the audience comes quickly enough, he will survive; otherwise he will die. But this time, the light fades away, ending the production before the actor has a chance to finish the anticipated scene.

The festival included some attempts to revive former historic productions, a singular example of postmodernity. Paradise now (1968-2018), directed by Michiel Vandevelde, is a production which seeks to rejuvenate the historic counter-culture production Paradise Now by the Living Theatre from 1968, but also, to present some events that have happened since then, and to reflect on what remains of the spirit of this year nowadays. In order to add a new spin of naivety to the production, and maybe also to differentiate it from the original, the director chose mostly teenage and child actors, ages 13-21 (Zulaa Anthenis, Sarah Bekambo, Jarko Bosmans, Bavo Buys, Vara Chavarria, Judith Engelen, Abigail Gypens, Lore Mertens, Anton Rys, Margot Timmermans, Bo Ban Meervenne, Esta Verborven, Aron Wouters). Dressed in vivid colors that recall the 60s but adapted to contemporary fashion (there are no flowers) the actors stand upstage at the beginning of the production behind a curtain of strings. The first part of the production was composed mostly with tableaux vivants. Upstage in big lettering appear the dates (2017, 2007, 1980, 1976, 1972, 1970…), or singular words or sentences that recall an historic event, character, or famous person, some of them positive, some terrible: Dubrovska Theatre, Abdula Ocalam, Sebrenica, Falklands, Soweto, the film the Titanic… and the actors collectively adopt a position that elicits the corresponding event. When the date 1968 appears, the actors begin to dance in a frenzied way, mixing with the audience or shouting slogans of 1968 to the public from downstage, delivered in their childlike voices. The allusion to the sexual revolution was also very present, with mimicry of sexual gestures and positions, some of the older actors even baring parts of their bodies as they mixed with the public.

Paradise Now. Photo: Don Snyder.

Although the gathering of the bodies imitating free love – without nudity – was well done, I felt closer to the benevolence and tenderness that results from attending a high school production than any invitation to a liberating atmosphere. But I was wrong, or at least my sentiment was not shared by most of the audience! When the actors asked if anybody in the audience wanted to come on stage, assuring that nobody would touch them, a significant number of all ages, who seemingly warmly identified with the production and the ideas expressed, volunteered without hesitation and occupied the entire vast stage of the Kaaittheater beside the actors. An interesting part of the production came during the last scene in the darkness. Every actor recited a text that expressed present opinions that starkly contrasted with the hopeful statements of 1968: “to be soft in the face to a violent political and economic system, seems the only possibility we are left with,” “I think we have to acknowledge that democracy is over, that political hope is dead, forever,” “We must abandon hope: the world machine is out of control, and human will is impotent. Only friendship is left,” “despair is the only appropriate intellectual position in this time,” “The present is the most difficult thing for us to live.” But also positive thoughts arising from despair: “albeit defeated and despairing, [social] movements are the carriers of a possibility that is not wholly extinguished,” “Radical thought, for me, is just that: the courage of hopelessness. And is that not the height of optimism?” “the ambivalence of the present situation must be maintained, because in this ambivalence is hidden the way towards our emancipation,” “To perceive, amidst the darkness, this light that tries to reach us but cannot – that is what it is to be contemporary.”

Paradise Now. Photo: Don Snyder.

The Iranian director Amir Reza Koohestani presented a new production, Summerless, a show that deals with some relationships in a school in Iran, transformed by the growth of capitalism in this country. The action takes place in front of a typical primary school entrance in Iran, with the stairs of the entrance and a merry-go-round in front of the door. Beside the entrance the wall is transformed into a screen on which the names of the months of the academic year during which the action is developed are projected.

With a very sober, almost distant, yet extremely convincing acting style, the actors (Mona Ahmadi, Salid Changizián, Leyla Rashidi, Juliette Rezai), play the principal of a primary school, her husband, who is also a painter and the art teacher, and a school girl’s mother. The production is interesting, as it shows social limits in Iran. Alluding to the development of private schools in Iran, the piece begins by showing how the school principal tries to encourage a mother into registering her daughter at the school, using its recent renovation as enticement. Then the elliptical action presents how her daughter, an eight years old little girl, falls in love with her art teacher and how the man is accused of showing a special interest in her, all of which is transmitted by the stories built up by the little girl and upon which her mother expands. The teacher leaves the school, accused by his own pregnant wife, the principal of the school, during which time their figures are projected onto the wall as colored shadows, symbolizing the importance of the social role which has been taken over by their personal life. In the last scene, the principal and her husband sit on the merry-go-round together again, talking with the little girl whose image is projected onto the screen. It is not, however, with the projection of the girl that the two teachers communicate, but in fact with the mother, who, with her back to the audience now takes on the role of her daughter. The little girl wants to go to her drawing teacher´s house during the summer to show him her drawings; the principal and the teacher try to convince her that she must stay at her parents´ house. The title invites us to believe that she succeeds in her desire, and that she thus ruins the couple´s summer.

Summerless. Photo: Luc Vleminckx

There were many other interesting Productions, such as La Plaza by the Spanish company El Conde de Torrefiel, directed by Pablo Gisbert and Tania Belenguer; or a wonderful musical production, Suite n.3. “Europe”, by Encyclopédie de la parole, directed by Joris Lacoste and the musician Pierre-Yves Macé.

There was a children’s theatre production Unforetold directed by Sara Vanhee. With seven young children, the director creates a piece based on stories from their imaginations and which is performed in almost total darkness. Illuminated by lights attached to some part, of their bodies, the unidentifiable children moved in the space, like moving forms in the darkness whilst their questions and endearing stories could be read by the audience projected on a screen upstage.

Some humorous productions had very imaginative actions, such as Mikado Remix a production by Louis Vanhaverbeke. This one-man show is mainly a parody of theatrical musicals. The songs, composed by the creator with humor and parodical repetitions, deal with important topics – the limits of what protects us and at the same time imprisons us, the sensation of loses, the relationships between our inner selves and our wordly life, the uniformity of the world and the uniformisation of individuals, nationalism, the loss of balance… –. Accompanied by different recorded music, the performer sings with the same rap rhythm. The audience could follow the lyrics that were displayed in Flemish and in French on a screen upstage. The production is based on the diverse structures that, with shrewdness, the performer builds up during the production: most of them are ridiculous and funny. For instance, in the first part of the production, the performer seemed to be trapped in a box, while singing a love song; later on, he puts a waffle maker a traditional Belgian cooking tool, on the top of a bar and prepares a waffle that he offers to the public… At the end of the production, he attaches a camera onto a bicycle and rides down the theatre stairs, going out of the Theatre to the nearby Place de la Bourse, while the audience is watching the images of this journey on the screen in the theatre. The performer comes back to give his final wave.

Mikado Remix. Photo: Leontien Allemeersch.

Dance

This year there were not were not as many dance productions as in previous years. Monument 0.4: Lores & praxes (Rituals of transformation), directed by Eszter Salamon, was an outstanding and perhaps the most interesting dance production of the festival. It was presented at ING Art Center, an arts exhibition venue, where it was performed in several different rooms. The dancers (Liza Baliasnaja, Sidney Barnes, Mario Barrantes Espinoza, Boglárka Börcsök, Amanda Barrio Charmelo, Stefan Govaart, Cherish Menzo, Sara Tan, Louise Tanoto, Tiran Willemse) moved alone or divided into changing groups from one space to the other. The audience could move freely to follow them. The production consisted of six hours of uninterrupted beautiful and innovative movements.

Monument. Photo: Inge Vermeiren.

The starting point was to learn and adapt older forms of war dances or dances of resistance from different parts of the world, in order to explore and find new kinds of movements, different from classical or conventional dance. This search was motivated by the desire to find new relationships with the world. The production showed a rich multiplicity of innovative movements, that cannot be easily summarized. It contained a mixture of different styles of movement that have never been combined before. The movements were very often executed individually, by groups of two people, or more. At times, two dancers played together with the same kind of movement. Among the movements were defensive ones, and movements reminiscent of war or some kind of transformed martial arts, many of which carried pain and trauma as frequent and prominent emotions. Many movements were created by imitation of reality, some inspired by images or paintings, but all undergoing a systematic transposition.

Within the production, despite the dancers being in different rooms, there were some sequences and variations of energy and rhythm that occurred simultaneously for all the performers: at some points the energy and rhythms were very vivid; whilst at others, the movements seemed slower. What the audience could see in each room was different, and always unexpected: At some point five performers gathered in a single space before making an incredibly rhythmical clapping movement; in another space, a dancer maintained fixed movements for more extended periods, adopting aggressive physical stances and facial expressions whilst looking at a member of the audience, like a threatening painting of a samurai. After three hours eight of them were on the floor shivering, performing similar movements. The songs, sounds, rhythmic knocks, slaps and claps were heard from one space to the other.

In some pauses, a dancer would take a member of the audience aside, and recite a monologue, whispering to the spectator. Each dancer had a different monologue. The monologues, despite each being unique, dealt fundamentally with the aesthetic of the production and its aims: to achieve decolonization of the physical movements which one has become accustomed to since the earliest moments of childhood, the homogenization beginning when somebody tells you how to act in certain circumstances, how to move in executing a given action. The learned movements are always hiding something, much like the white walls of a museum. There is a multiplicity of possible movements; New movements allow for the obsolescence of archaic ones; they encourage an understanding of multiplicity; they liberate; new movements inspire the process of finding oneself. They advocate an understanding of things that would not be discovered otherwise. It is also time to thank our body. It’s time to be conscious of the movements we make, with our arms and legs: it’s our responsibility to free our body from homogenization.

As unique as they were exceptional, many of these productions were beyond the usual boundaries of the genres. Banataba by Faustin Linyekula was a wonderful and moving dance production performed outside of the Musée Royal d´Art d´Afrique Centrale, built by King Leopold II of Belgium to gather works of art from his colonies, and which is currently closed for renovations. The performance begins with Faustin Linyekula singing and saying words in front of one of the huge lateral doors of the museum’s main building. This allows Faustin Linyekula to ironise about it as the “forbidden museum.” The closed door becomes the metaphor for the European attitude concerning spoiled and abandoned Africa.

The production was to have taken place inside the museum, showing the sculptures of the Lengula ethnic group, the clan of Faustin Linyekula´mother, from the Congo, but as aforementioned, this was not logistically possible. After these first moments, Faustin Linyekula and his partner, Moya Michael, walk to another part of the garden in front of a modern building, where the seating has been prepared for the audience. He combines storytelling and dancing. This particular production began in the Metropolitan Museum of New York where he saw a Lengula sculpture kept in the museum – when he travels he tries to see as many elements as possible of the culture of the Congo, now scattered all over the world. He decided to make a production using this sculpture. However he found it difficult to grasp the sense of the sculpture as a whole. For really understanding what the sculpture means, to hear its story, he traveled to Banataba, his mother´s village in the Congo. He also took his mother and uncle with him. He dances to express his trip, his happiness, and also his suffering, with traditional music and rhythms. He and his partner express their despair in attempting to grasp their origin with a dance. Repeatedly he adopts the position of the sculpture. When they reach the village, a recorded video of a dance is displayed on a screen. Nonetheless after a long trip, he discovers that the village is not his village anymore, just as it is no longer the village of his mother or his uncle after forty years without returning to it. After such a long time and at such a great distance, they have become foreigners. The sculpture has been blessed in a ritual by the people of the village. Instead of bringing an original sculpture to New York again he decides to leave it in the village and to ask a craftsman to carve a new sculpture that he will bring back to New York, instead of repeating the spoliation of his country. They finally assemble the different parts of the sculpture. At the end of the production the two dancers walk back to their first location, in front of the closed door, to close the production to the public.

aCORdo, directed by the Brazilian choreographer Alice Ripoll and the company REC, was a dance production that surprised everyone with its originality. Without great technical achievements, it was warmly received by the public, on account of its inventive movements and actions. The company was founded nine years ago as the result of the action of a charitable organization in a favela in Rio de Janeiro. aCORdo is the third production of which Alice Ripoll served as director. The group is formed of five performers (Alan Ferreira, Leandro Coala, Tony Hewerton, and Romulo Galvao) although there were only four of them in the performance I attended. They all dressed with the same kind of uniform, each of them a single colour, reminding the spectators of prisoners. The audience was seated on a simple row of chairs forming a square with the walls of the room; the performers in the middle.

The production seemed to be an ironic metaphor of their evolution as a group but how, unavoidably drawn together by their social background, they ended up in another kind of social immobility. The group is initially lying on the floor: in their first movements, they all crawl on each other. They are then motionless or use very slight movements. Gradually they all succeed in standing up. They all do individual dance movements; there are not conventional movements. their dance is rather rhythmic with a nervous quality and profusely energetic. They then begin to make collective movements and dance actions. This collective coordination gives them strength. They begin to involve the public: they take one actor and place him horizontally on the knees of the audience for a few instants until the body falls to the floor; they repeat this movement. Immediately after, they each begin to take an object belonging to a spectator (glasses, backpack, shoes, wallet…) and they put them in one of their pockets or give them to another member of the audience. They repeat this with all the members of the audience and suddenly stop in front of the wall, as though they have been arrested, leaning against the wall with their hands resting on it, high above their heads, and their legs apart. The audience stands up and tries to recover what has been taken, asking the others members of the audience, to recover their backpacks, or search in the pockets of the performers, as if they were policemen with delinquents. When the audience leave, the dancers remain motionless, holding the same positions.

There were many attractive and outstanding dance productions. Among them was Inoah by the Brazilian choreographer Bruno Beltrao and the company Grupo de Rua, which performs hip-hop choreography. The group came from Narica, close to the city of Niteroi, in the region of Rio de Janeiro. Whilst at its core the group perform hip-hop, at times, the ten dancers also play to deconstruct familiar hip-hop patterns, which they mix with other dance styles, sometimes recognizable gestures of daily life.

Other performnce

One of the features of the Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018 was that there were many original performances, each of them very different from each other and each challenging the limits of the performing arts. Among the more challenging productions, without expecting it, was the performance by Philipp Gehmacher, my shape, your words, their grey. Philipp Gehmacher is an Austrian performer who presented a strange and very poetic production that took place in the Wiels, a former brewery which now serves as a museum of modern art, where the exhibition and the performance were displayed. The production was created in 2013 and has since been shown in a variety of venues, from dance studios to museums. It involves several arrangements which adjust depending on the space where it is shown. Unusually, the performance is set in an exhibition of objects crafted by the artist that the audience could visit before or after the production. The majority of these objects are made of chipboard with geometric forms like panels and partial boxes, some of which are painted. Some could be considered as sculptures whilst most of them are ambiguous, seemingly incomplete, or demanding further work. The performance was about the color grey. This color serves as a metaphor for a new space with less tension and renewed possibilities, being neither the white space of the exhibitions, nor the black box of the theatre. A few sentences written on canvases summarized some of the main ideas of the production: “There is no need to be dramatic.” In fact, maybe the performance’s major originality is in its complete lack of dramatic tension. With music played in the space by Gérald Kurdian, Philipp Gehmacher moves his painting from one part of the room to another, executing awkward movements that are, at times, reminiscent of a disturbed person, or maybe for him, an image of a grey person. The audience watched these simple movements, relaxing with a smile. The grey seems to be a simple demand for normality, in a gesture that declares liberation: “great life I leave it for our imagination.” The performance deals with the problem of visibility of the work of art, how the audience receives it, and where the displayed objects come from. For fifty minutes, there was no story, just the coherence of the movements combined with the discourse.

my shape, your words, their grey. Photo: Benjamin Boar.

Your Word in my Mouth, by Anna Rispoli, Lotte Lindner and Till Steinbrenner was a performance that took place every time in a different location. When I attended it, it took place in a hairdressing salon, in the popular neighborhood of Matongué. The audience were guided to the hairdressing salon, and invited to take their seats in this small space, the intimacy of which forced them to watch the other audience members. Each spectator receives a booklet at the entrance with the play involving eight characters, each from different backgrounds, with different jobs and having diverse opinions about the main topic: love and sexual desire. The members of the audience who wished could read a part, and the performance only began when there was a volunteer for each part. The dialogues had all been taken from real life, between November 2017 and April 2018 and were then assembled by the director. They expressed current, often controversial positions. They were presented in columns in the booklet in order to make it more immediately apparent who was speaking. The expression of the experiences of the character were the occasion to express hidden desires as well as the prejudices. An interruption in the middle allowed time to serve a glass of liquor to each spectator. The readers were identified with a character, becoming actors for one hour and a half, invited to take their time to read as they felt it necessary. The performance depended on the attitude of the members of the audience and their sense of humor.

Your Word in my Mouth. Photo: Bea Borgers.

Many productions had a political and social concern. Among them, Boundary Games, directed by Lea Drouet. Six performers (Frédéric Bernier, Madeleine Fournier, Catherine Hershey, Simon Loiseau, Marion Menan, Bastien Mignot) without reciting any text, handled blankets that symbolize immigration and the relationships it provoked. At different points, the performers spread the blankets out on the stage, used them to draw lines on the floor like boundaries that were immediately changed, changing their attitudes towards each other. They lay down on the blankets, made diverse formations like small volcanic mountains or Archipelago islands, maybe symbolizing the immigrant communities, and finally, they created a new and meticulous design on stage based on blankets, that each member of the audience could interpret in a different way.

A.G.U.A. by Gwendoline Robin, was both an installation and a beautiful performance with an ecological concern about water and its excessive use. Other performances explored other kinds of limits. The performance Farci.e, by Sorour Darabi, an Iranian transsexual, took as a starting point that gender does not exist in Farsi, using a lecture as the main action within the play. He created with his movements a tense image of desire and of the fragility caused by the performer’s own personal transition between genders. W.I.T.C.H.E.S Constellation, by Latifa Laâbissi, and Título em suspensao, by Eduardo Fukushima, explored the tension of immobility and the distortion of time, inviting the audience to become aware of their own perception. Deep Etude by Alma Söderberg was a wonderful performance based solely on rhythms and rhythmic structures.

Cinema

The Kunstenfestivaldesarts also presented several experimental films. Among them, three short films Source/ Orientations/ Foyer by the Tunisian Filmmaker Ismaël Bahri. Source (2016, 8 minutes) shows two hands holding a page. The page begins to burn slowly from the center. It shows the phenomenon of being slowly consumed by fire without a flame. The white page disappears slowly, becoming a huge hole. The fixed image – as was the case in La Plaza by El Conde de Torrefiel – provokes fascination, as a metaphor for everything that disappears. Orientation (2010, 20 min.) the second film, was the image of a glass full of black ink. The filmmaker moves the glass through the streets of Tunis. The only image was a glass full to the brim, filmed from above. | The main focus of the film| remains out of shot, which looks like a device to provoke reactions, through which the viewers are forced to approach reality indirectly. The film records the sounds, peripheral views, and all the interventions of people who approach and speak to the filmmaker, some of which are quite comical. Foyer (2016, 32 min.), the third film, pushes this idea further. The image filmed is a white sheet of paper, moved by the wind. The filmmaker moves through the city of Tunis and is approached by many people, who are intrigued by what he is doing. The audience hears diverse conversations that surreptitiously depict an agitated social and political landscape. The police arrest the filmmaker, believing that he is filming the police station and that he could be a terrorist and eventually they release him, proud of him, when they discover that he is in fact a filmmaker who teaches in France…

Sanctuary, an example of “expanded cinema,” directed by Carlos Casas, was shown in the former chapel of the Brigittines. The film presents parallels between the threat posed to a man living in Sri-Lanka with an elephant, who has to flee from a few men who come to catch or kill him, and the threat of a natural catastrophe. The images of the film stop when a flash of lightning illuminates the roof of the chapel, while an elaborate sound and resonances seem to engulf the entire space, transmitting the amazing idea of a catastrophe, even evoking an apocalypse-like situation.

There were also animated films like Tree Identification for Beginners, by Yao Barrada, which showed geometric figures while a voice narrated the travel of the director´s mother in the 1950s. invited to visit the United States, with other young Africans.

Other activities

At the Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018, there were also a wide array of activities relating to May 1968, its fiftieth anniversary. These activities, called “The May Events,” reflected on the ideology of May 68; about how it could be taken as a starting point for new reflections about today’s society, and also how everything has changed. Many of these events took place in the I.N.S.A.S., the most important theatre school of Brussels. For instance, Pamina de Coulin did a series of banners, displayed on the walls of I.N.S.A.S, with slogans from May 1968, or at least slogans with a similar rebellious style. El pasado nunca muere, ni siquiera es pasado, directed by the Mexican group “Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol” made a critique of the May ideology and its negative consequences. The production criticized how the nostalgia and idealization that the events incited prevented moderate reforms in the years that followed, with its continued negative influence made manifest in the 2012 Mexican movement “yo soy 231.” A few performances and a concert, on the 19th May, “A Night on The Multiplicities of 1968,” aimed to show the variety of ideas and practices that surfaced from May 1968.

An event that clearly endeavored to remind the public of the spirit of May 1968 was a Decolonial Guided Tour guided by a member of the Collectif Mémoire coloniale & Lutte contre les discriminations (Collective of Colonial Memory and Struggle against discriminations), an association of African people who try to deconstruct the discourse of the colonizers, exploring the terrible reality of the Belgian colonisation of Congo, and ultimately to fight against the present day discrimination faced by those of black African descent in Belgium and Europe. For this, they guided the event participants through the neighborhood of Matongé, where all the colonial institutions created by King Leopold II and his nephew King Albert were assembled. With the independence of Congo, this neighborhood became a place where African immigrants settled in Brussels. The tour stopped in some symbolic places, explaining the diverse forms of discrimination.

Decolonial Guided Tour. Photo: Timothy Lawrence.

There were also countless talks with the directors of the productions, workshops with artists, and a reading club, The political Party – A mobile Public library that gathers to discuss books tackling present day problems.

Manuel García Martinez is Senior Lecturer in French Literature at the University of Santiago de Compostela. He wrote his Ph.D. in Drama Studies at University Paris 8. His research interests are time and rhythm in theatrical productions/performances and in dramatic texts, the French contemporary theatre, and the Canadian theatre.

- European Stages, vol. 12, no. 1 (Fall 2018)Editorial Board:Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-EditorEditorial Staff:Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing EditorAdvisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis ZatlinTable of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 (Part II) by Beate Hein Bennett

- Report from Berlin (June 2018) by Marvin Carlson

- Othello, Shakespeare’s New Globe by Neil Forsyth

- Resistance Through Feminist Dramaturgy: No Way Out by Flight of the Escales by Meral Hermanci

- 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe by Anna Jennings

- The Avignon Arts Festival 2018 (July 6 – 24): Intolerance, Cruelty and Bravery by Philippa Wehle

- Le Triomphe de l’Amour : Les Bouffes-du-Nord, Paris, June 15—July 13, 2018 by Joan Templeton

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018 of Brussels (Belgium) by Manuel García Martínez

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Contemporary Nordic Performance at the 2018 Arctic Arts Festival by Andrew Friedman

- A Piece of Pain, Joy and Hope: The 2018 International Ibsen Festival by Eylem Ejder

- The 2018 Ingmar Bergman International Theater Festival by Stan Schwartz

- A Conversation With Eirik Stubø by Stan Schwartz

- The Estonian Theatre Festival, Tartu 2018: A ‘Tale of the Century’ by Dr. Mischa Twitchin

- BITEF 52, World Without Us: Fascism, Democracy and Difficult Futures by Bryce Lease

- Unfamiliar Actors, New Audiences by Pirkko Koski

- Corruption, capitalism, class, memory and the staging of difficult pasts: Barcelona theatre and the summer of 2018 by Maria Delgado

- Reframing past and present: Madrid theatre 2018 by Maria Delgado

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.eduMartin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018

ale of the Century’ by Dr. Mischa Twitchin

- BITEF 52, World Without Us: Fascism, Democracy and Difficult Futures by Bryce Lease

- Unfamiliar Actors, New Audiences by Pirkko Koski

- Corruption, capitalism, class, memory and the staging of difficult pasts: Barcelona theatre and the summer of 2018 by Maria Delgado

- Reframing past and present: Madrid theatre 2018 by Maria Delgado

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018