One of the phenomena that can easily be noticed when looking at the post-2000s Turkish Theatre is the increase of monodrama. A range of subjects from women’s issues to transgender persons, language, identity problems related to migration, war and political pressure can be found in the repertory of monodrama which mostly emerges in storytelling form and is usually presented on empty stages. In this essay, I would like to point out this new trend epitomizing the changing landscape of theatre and performance studies in Turkey: the increasing of monodrama or solo-shows in storytelling form. I will try to suggest some possible reasons that lead to this increase and how it may have a transformative effect on Turkish theatre, through some notable examples of this phenomenon. At this point, the critical questions the essay tries to point out are: Is the contemporary Turkish theatre gradually becoming the theatre of monodrama? Is this a sign of closure, a contraction for theatre studies, or a possibility of conceiving new opportunities? (See my essay “From Melodrama to Monodrama: A Preliminary Introduction to Modern Turkish Theatre”, Artism, December, 2017.)

Turkish theatre has been passing through a change worth noting over the last decade. Especially in İstanbul, the most populated city in the country, there has been a dynamic theatrical life despite the socio-political crisis, the discussion of “authoritarianism” and censorship in art. But the distinctive feature of this period is not only the increase of the number of new groups, playwrights, new venues, or independent theatres (even without any subsidies) but rather their addressing current issues and telling new and different stories in a way that has never been seen on stage before.

Almost half of the productions staged in the last few theatre seasons are the monodramas written by new young playwrights and staged by new independent theatres. The audience is shown an actor alone telling the story of a lonely character living in a conflicting society and performing it on an almost empty, dark, gloomy stage. There are various subjects in monodrama-form staged by different theatre collectives which can exemplify changing dramatic subjects and forms in contemporary theatre of Turkey. For example, ten years ago it was not possible to witness on stage the story of a transgender person or the story of Saturday Mothers as well as the feminist and queer dramaturgies, using physical theatre techniques from buffoon to clown. Therefore, the stage of monodrama seems to me as a pathway to observe and understand what is happening in contemporary Turkish theatre culture. It is like a combination of different experimental endeavors or like a kernel, a bud containing all this diversity that is ready to explode at any moment.

The repertoire of the monodrama

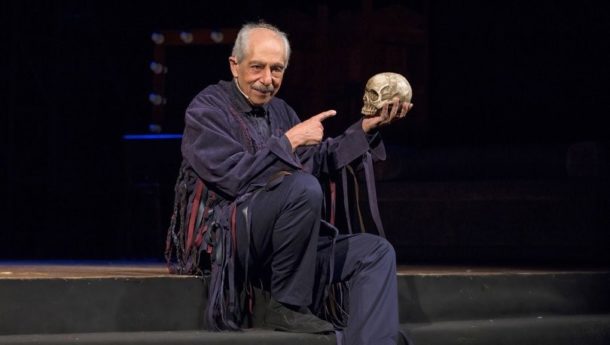

Some of these monodramas are adaptations of biographies from recent history bringing to the stage forgotten and concealed stories of leading Turkish historico-theatrical figures such as the poet Nazım Hikmet and Afife Jale, showing the first Muslim actress on the Ottoman-Turkish stage. Genco Erkal’s solo-performances, especially his last one Merhaba (2018) (Hello) combining Nazım Hikmet’s poems and his life in jail with the poems by Brecht, Shakespeare, and Can Yücel, is one of the most well-known examples of such experimentation. Another performance which is a collage of selected poems by Nazım Hikmet, is Ran, a narrative of a man in prison, performed and adapted by Yurdaer Okur. These performances are based on an idea of resisting the tyranny of daily life. This is why they turn their attention to recent history shedding a light on how a single person struggled against problems, pressures, and challenges s/he encountered in the past and reminding the audience of those which we are passing through today.

Genco Erkal in Merhaba (Hello). Photo Credit: Dostlar Tiyatrosu.

Another example is Melek, by the leading feminist theatre group Theatre Painted Bird. Melek (2013) presents the story of Turkish opera artist Melek Kobra (performed by Yeşim Koçak) who lived in early period of the Turkish Republic and died in her late twenties in a sanitarium because of tuberculosis. Director Jale Karabekir’s feminist approach is based on the deconstruction of the cliched image of the woman with tuberculosis found in Turkish melodrama movies during the period called Yeşilçam. In doing so, it draws attention from a critical perspective to the early Turkish modernity experience, and how women’s life was and still has been shaped in it (see Emre Erdem, “A Feminist Tuberculosis Melodrama: Melek By Theatre Painted Bird”, Arab Stages, Volume 2, Number 1 [Fall 2015]).

As in Melek, one of the common subjects in many of the current monodramas is the women’s issue. These stories—which we are used to seeing only on third-page news—question gender, patriarchal relations and male dominance shaping a woman’s life. Lena, Leyla, and Others (2016) written by Zehra İpşiroğlu, is just one example of such a feminist monodrama. It tells the story of an Ukranian woman Lena whose name is changed to Leyla after getting married to a conservative Turkish man in Istanbul. Lena (performed by Cihan Bıkmaz) is in a mental hospital because of the masculine world that turns her life into an asylum. She believes that she needs to clarify her life, and to do it she needs to write and tell what happened to her.

Cihan Bıkmaz in Lena, Leyla and Others, written by Zehra İpşiroğlu, directed by Ayla Algan. Photo Credit: Bakırköy Belediye Tiyatrosu.

Some of the current monodramas are adaptations of well-known Turkish novels, poems, and short stories written after 1970’s such as Oğuz Atay’s Tehlikeli Oyunlar (Dangerous Games), Latife Tekin’s Sevgili Arsız Ölüm (Dear Shameless Death), Turgut Uyar’s Dünyanın En Güzel Arabistan’ı (The Most Beautiful Arabia of the World); or the adaptations of classical texts such as Macbeth, Faust, and Peer Gynt. I believe that one performance in particular, which was presented by theatre group Seyyar Sahne and became quite popular, lead to the emergence of many solo-performances by recently graduated artists. At this point, Seyyar Sahne’s building a theatre madrasa (Tiyatro Medresesi) in Şirince and organizing workshops and festivals on monodramas has had a great influence on new theatre practices.

Seyyar Sahne is a theatre collective investigating the dramatic and theatrical possibilities of non-theatrical texts such as novels. To do this, they blend storytelling and physical theatre techniques as an embodiment of the single actor on an empty stage. Their most popular and famous production is Dangerous Games, a stage adaptation of Turkish novelist Oğuz Atay’s piece under the same title. Premiered in 2008 and still being staged in this theatre season, Dangerous Games tells the story of the main character Hikmet Benol (performed by Erdem Şenocak) living alone in a slum in very poor conditions and speaking with his imagined friends and neighbors whom he blames, ridicules, and with whom he sometimes shares his innermost thoughts and feelings. During the performance, we are shown two swings and one performer. During his nearly three-hour-long spoken performance which takes place without any sound or light effects, Şenocak performs the story using all parts of his body, performing different characters surrounding Hikmet’s life, wiggling his toes and fingers. As in the novel, what is revealed in this performance is not only Hikmet’s world, enshrouded with conceit, passion, ambition, defeat, unsuccessfulness, and humor, but also how Turkish modernity has shaped and is still shaping the lives of people.

Erdem Şenocak in Tehlikeli Oyunlar (Dangerous Games) directed by Celal Mordeniz and staged by Seyyar Sahne. Photo Credit: Seyyar Sahne.

Other monodramas are new texts telling the stories of those named “other” as being repressed, unheard and living at the margins. These performances express the situation of the transgendered person being exposed to violence and prostitution and those of a street child or a woman exposed to male violence.

Esmeray is telling her story of becoming a mussel seller after becoming acquainted with feminism where in the past she was a sex worker. Photo Credit: Özge Özgüner.

The pioneer example of the field of politicizing transgender life stories is Cadının Bohçası (The Sack of the Witch, 2007-2019) written and performed by the feminist, activist and trans performer Esmeray. The performance is based on her real-life story from her childhood in Kars, eastern Turkey, to her migration to Istanbul. She works in different jobs but then becomes a sex worker. Her life is difficult because, as well as being trans, she is also Kurdish. When she acquaints us with ideas of feminism, women’s rights, and leftism she becomes an activist struggling for sexual and ethnic identity and gives up sex labor. Based on a feminist and humorous approach, her performance takes the audience into a journey from the 80’s and 90’s to 2000’s, showing socio-political events and revealing relations based on gender, national, ethnicity and class.

A new performance telling the transgender person’s story is Eylül, written and performed by a young award winning actor Uğur Kanbay. Eylül is a play describing a transgender woman Eylül (meaning September) in her twenties, who left her family and arrived to Istanbul to live as her true gender. The actor’s performance begins in a one-room house where Eylül tells how she became a sex-worker, her military checkup, the man she loved, her family, her father’s sexual abuse, etc.

Eylül (Ugur Kanbay) is telling about her military checkup. Photo Credit: Erdi Aydın.

Some monodramas are based on a meta-theatrical structure that questions the concerns of acting and theatre in Turkey. In such monodramas, the narrator/performer may portray a callow actress who tells the poor conditions of making theatre and the difficulties of becoming an actress in Turkey in a humorous manner. One hopelessly wishes to be awarded as the best actress of the year (Yılın En İyi Kadın Oyuncusu [The Best Actress of The Year], performed by İpek Türktan Kaynak; ironically Kaynak got the best actress award with her performance in 2016). Another wishes to act in a TV series, which has become a great phenomenon among the actors to earn money. Ironically, however, she becomes a femme fatale both in acting and life (Yan Rol/ Supporting Role performed by Başak Kara). A final example of this sort of narrative is Benden Bu Kadar (That’s All from Me), written and performed by Burcu Hallaçoğlu (directed by Celal Mordeniz, staged by Seyyar Sahne in 2018-2019). This is a narrative of a callow and naive girl who questions her existence in theatre and life while trying to understand how she can struggle with “being on the world stage” without leaving a remarkable trace.

İpek Tüktan Kaynak in The Best Actress of the Year. Here she rehearsals her speech of thanks should she win the best actress prize. Photo Credit: Seyyar Sahne.

There are also others presenting more political stories. GalataPerform’s new play, for example, Yüz Yılın Evi (House of Hundred, a solo performance written by Ferdi Çetin and Yeşim Özsoy, performed and directed by Yeşim Özsoy), tells the story of an old house that witnesses the late Ottoman and early Republic period, and reveals the experience of Turkish modernity that has consisted of demolishment, destruction, exile and re-building through the wreck of the title building. What makes it different from other monodramas is not only the politic dimensions that reanimate the social memory but also the narrative structure. It tells the story from the perspectives of different objects located in this house, not from the eye of a particular character. Based on an investigations into the concepts of “haunted houses”, “national identity”, and “history,” Özsoy’s performance is a combination of fiction, real life and the autobiography of her grandmother, who lived in this old house.

Yeşim Özsoy in House of Hundred (Yüz Yılın Evi). Photo Credit: Ali Güler.

The Şermola Performans, which is concerned with the Kurdish question, is a leading theatre group interested in developing possible ways for a new acting and storytelling style in monodrama form in order to present a theatrical experience that pushes the possibilities of the staging. Mirza Metin, one of the co-founders of Şermola Performans, has been performing his famous solo show Disco Number 5 since 2011. It tells the story of a revolutionary captive in Diyarbakır Prison known as a torture house after the coup in 1980. The difference of this monodrama is not only its staging in Kurdish and its involvement with traumatic political issues, but also its presenting the story through the eye of a spider.

Ahmet Melih Yılmaz (Avzer) in It’s Never Gonna be the Same. Written by Şamil Yılmaz and directed by Sezen Keser. Photo Credit: Mek’an Sahne.

It’s Never Gonna Be the Same: Wipe Your Tears (Artık Hiçbii’şii Eskisi Gibi Olmayacak Sil Göz Yaşlarını, 2013-2015), written by leading playwright Şâmil Yılmaz, is another example presenting the political situation of the country, namely Occupy Gezi in 2013, through the eyes of a street child Avzer (performed by Ahmet Melih Yılmaz, staged by Mek’an Sahne). Mekan Sahne says that “everything we see and experience on the streets will be on the stage, that there will be no gap between the two.” It describes the othered individuals or the “othered” sides within each individual. This is what we the audience see or witness in Yılmaz’s monodramas street performances with arabesque rap music, a character smoking weed, cursing, speaking the street language like Avzer. This play is a palpable example of the narrative of loneliness. Avzer, who lives alone in the streets, is someone that people can encounter in daily life. What the new theatre in Turkey tries to do, particularly that of Mek’an Sahne, is to transform this daily and ordinary encounter with the named ‘Other’ to both a theatrical and real encounter on an empty stage. To do this, Avzer directly tells his story to the audience by introducing himself as “me, Avzer.” While sitting on a chair during the performance, he tells his story and sometimes asks questions both to himself and to the audience. What he shares with the audience is the description of a turning point in his life because of the occupation of the streets where he lives. The playwright Yılmaz never refers in his play to the Gezi Park Protests that spread to almost every city of Turkey in 2013. These were not only against Turkey’s current ruling party, but also the whole ideological stance of the Turkish Republic which rejects and represses differences, alterity, and otherness. Thus, we, the audience know this performance tells the story of Gezi and also what people shared in common during that occupation. When Avzer tells of his encounters with other people gathering in the parks, he begins to change, especially after meeting with “the girl and the boy.” What this performance does is carry a sense of being together, being in common, despite the loneliness of the individual. It transforms collective loneliness to a sense of communitas.

Toward a theatre of a monodrama

Examples can be reproduced at length. My aim is not to give a complete view of these monodramas, but rather to draw attention to the different experiments, social and theatrical issues involved, and to think about the reasons behind them while developing questions on how this situation might affect Turkish theatre in the near future. So, the question arises: why do theatre makers transform this sort of narrative—from biography, novels or poems, to stories of daily life—into monodrama form as a narrative of the isolated and lonely person in the society, performed by an actor alone on stage? Or, why is Turkish theatre so eager to tell such stories? Perhaps, it shows, as theatre professor Martin Puchner told me about this concern, “there is something important going on in contemporary Turkish society that has to do with an emphasis on individual, isolated voice.” Or as Turkish theatre scholar Ayşegül Yüksel asserts:

The easy “portability” of solo-performances provides great comfort to the producers today, where theatre productions are becoming increasingly expensive. Solo performances are often included in the repertory of theaters. Because it increases the opportunity to participate in tours or festivals at the national or international area.(“Sanatçılığın Ustalığını Sınayan Bir Tiyatro Türü” [A Theatre Genre That Tests the Artist’s Mastery”, Teb Oyun 37, p. 52.).

Though I think it can be a proper theatrical form reflecting the living experience of contemporary Turkish’ socio-political climate which is recently identified with “polarization,” “othering,” and “loneliness,” it would be an oversimplification to explain this “mono-dramatic turn” on economic components like the easy portability of the form, or as a symptom of the socio-political condition of Turkey today. But to receive monodrama only as a symptom of socio-political crisis and a mono-cultural, self-centered life, leads us to misconceive what changes are actually being produced on Turkish stages. Furthermore, when the producers of these monodramas are asked what their intention was, they mostly point to the same motivations: “the magic or the power of the narrative,” “there are plenty of things in this country to tell, to expose which we long suppressed.” Some say “it is the rebirth of traditional storytelling forms” which have persisted in Anatolia, like Kurdish storytelling Dengbej or the meddah (storyteller) in the Ottoman theatre. Some refer to the new experimental search to tell new stories and new forms. For them, monodrama is a kind of “poor theatre.”

However, this quest is by no means an aesthetic search detached from the cultural and political situation of the society in which they live. On the contrary, in the performances, different socio-political dynamics are intertwined with the suppressed and visible cultural context relating to the formation of modern culture in Turkey. Mek’an Sahne, for example, sees this “essence” as a moment in narrative shared by the spectator and the actor, and seeks to treat this moment as both a theatrical and real encounter between two, helping to understand and explain the “other voices” which are excluded from the history. On the other hand, “ba-interdiciplinary Theatre (ba-disiplinlerarası Tiyatro Topluluğu), founded by Ferdi Çetin and Yusuf Demirkol, is interested in “describing what cannot be narratable, as well as producing mono-performative works where all the elements of the staging are of equal value.” Their last solo performance Letters for a Tractor from the Museum with a Memory of Loss (Hafızasını Kaybeden Müzeden Bir Traktöre Mektuplar) presents the correspondence between a tractor and a museum, from the body of a woman performer, which is an embodiment of a monumental museum reminding us of the Louvre in Paris with its pyramidal stage design.

Therefore, the sociological, economic, political arguments mentioned above cannot fully explain the increase of monodrama. But, they are not completely out of the scope of this concern. What is crucial here is one major consequence of such work: that the stage (both geometrically and methodologically) is becoming more and more narrow. With the emergence of black box theatres with a capacity of maximum 100 audience members, the stage is introverted and isolated in a traumatic way by an actor alone performing a lonely person in this society. On the other hand, it becomes clear that theatrical reality reflects the social and political changes more closely than ever before. Is this narrowness or isolation, a sign of closure and obstruction because of the audience’s encounter with the character’s traumatic story? Does it reflect new economic pressures? Or is it a sign of the opening up of new possibilities in Turkish theatre?

As Turkish theatre critic Handan Salta asserts in her reviewing of the monodrama Kader Can, the military memoirs of a rapper boy, “we can grasp the traces of social structure built upon oppositions and polarizations through the character’s personality and his reactions” in monodramas (Theatre Times, posted on 5.03.2019). This is because most of them present the gaps between individual and society, between individual and ideological pressures, and also the social differences. This gap leads to a sense of loneliness and isolation as much as it presents individual and social conflicts. In this respect, it is possible to read and understand certain social, individual, political codes and determinations in monodramas with the narrative of a single person. They all constitute a kind of subtext of Turkish modern culture. At some point, it is promising that these subjects, which have long been exiled to off-stage, are meeting with the audience. Hereafter, the stage is a meeting point of differences, a place for the repressed and the denied. It leads to a sense of being together, a sense of communitas through one’s loneliness, as long as the audience member feels what s/he has in common with the character in the story. Many of them give the audience a piece of hope and resistance. But there is also other side of the coin. As the number of monodramas gradually increases, the monologue dominates the dialogue, theatre experience changes as well. In such an age, everyone can easily become a storyteller, playwright, actor, director. Although I think this situation has positive and transformative effects on the Turkish theatre, it will be interesting to see what kind of things will occur because of the audience’s encounter with character’s traumatic story on increasingly numerous black box stages, and thus how this mono dramatic theatre will transform the art in near future.

Eylem Ejder is a PhD candidate in the Department of Theatre at Ankara University, Turkey. She is a theatre critic, researcher based in Istanbul and the co-editor of the theatre magazine Oyun (Play). Her PhD studies are being supported by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) within the National PhD Fellowship Programme. For more information about her works: https://ankara.academia.edu/EylemEjder and for her personal blog https://kritikeylem.wordpress.com/

European Stages, vol. 13, no. 1 (Spring 2019)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Introductory Note by Kalina Stefanova.

- “Andrzej Tadeusz Wirth (1927 – 2019) – White on White” by Krystyna Illakowicz.

- Lithuanian Marriage in Warsaw or The Last Production of the Great Eimuntas Nekrošius by Artur Duda.

- “My, Żydzi polscy [We, Polish Jews]”: A Review of Notes from Exile by Dominika Laster.

- A Report on the State of Our Society, According to Jiří Havelk in The Fellowship of Owners at VOSTO5, Prague, and Elites, at the Slovak National Theater, Bratislava by Jitka Šotkovská.

- About Life as Something We Borrow. On the Stages of Pilsen (In the 26 th edition of the International Theatre Festival There) by Kalina Stefanova.

- Redesigning Multiculturalism or Japanese Encounters in Sibiu, Romani, The Scarlet Princess, written and directed by Silviu Purcărete, inspired by Tsuruya Namboku IV’s Sakura Hime Azuma Bunshô by Ion M. Tomuș.

- About Globalization: A “Venice Merchant” on Wall Street, at the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj in Romania by Maria Zărnescu.

- The Patriots, Mary Stuart and Ivanov and the Rise of the Drama Ensemble of the National Theatre in Belgrade by Ksenija Radulović.

- The Unseen Theatre Company or How to See Beyond the Visible: The Shadow of My Soul and the Theatre of Velimir Velev by Gergana Traykova.

- Multilingual Pirandello, Understandable to Everyone: The Mountain Giants at the Croatian National Theatre “Ivan pl. Zajc”, Rijeka by Kim Cuculić.

- The return of the repressed: the ghosts of the past haunt Barcelona’s stages by Maria M. Delgado.

- A poetics of memory on the Madrid stage (2018) by Maria M. Delgado.

- The Danish National Theatre System and the Danish National School of Performing Arts: December in Copenhagen 2018 by Steve Earnest.

- Towards a Theatre of Monodrama in Turkey 1 by Eylem Ejder.

- Where Is Truth? Justiz by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at the Schauspielhaus Zürich by Katrin Hilbe.

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson.

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019