By Kathleen Cioffi

On March 3, 2021, Jerzy Limon, the founder and artistic director of the Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre in Poland, died of Covid-19 at the age of seventy. A man of many talents, Limon—a professor of English, Shakespearean, theatre historian, drama theorist, essayist, translator, and novelist—left a lasting mark on both the scholarly world of theatre specialists and the artistic world of theatre practitioners. He wrote many important scholarly works on Elizabethan theatre history as well as on drama theory. He was also an inspiring teacher, a witty raconteur, a good friend, and, as the editor of Teatr magazine, Jacek Kopciński, said in an interview published after Limon’s death on the e-teatr.pl website, “gentleman w każdym calu” (every inch a gentleman). However, it was through the gradual fulfillment of a dream—first, by starting a foundation, then by establishing an annual Shakespeare festival, and, finally, by building a Shakespeare theatre in Gdańsk—that he not only achieved the fulfillment of that dream but also had an enormous impact on Polish and European culture.

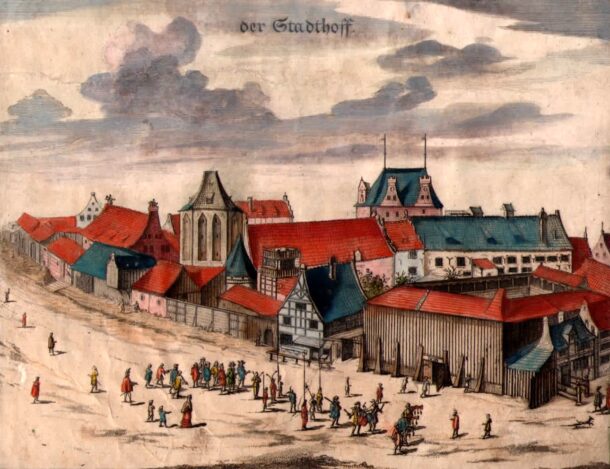

I first met Jurek (the Polish nickname for Jerzy) in the mid-1980s, when my husband and I taught in the English Institute at the University of Gdańsk, where Limon was the deputy director of the Institute. He had already made a name for himself as a theatre historian through his research on the Fencing School, the first public theatre in Poland. While working on his doctorate at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, he had compared the structure of the Fortune Theatre in London, known from Philip Henslowe’s construction contract, and that of the Fencing School, pictured in a 1687 engraving by Dutch artist Peter Willer. Even prior to defending his dissertation, he had published articles in the Polish journal Pamiętnik Teatralny and the British journal Shakespeare Survey on this subject. For the dissertation (defended in 1979), he also meticulously examined all petitions and applications to perform submitted by English actors to city councils and at aristocratic courts in the Gdańsk area. He was thus able to establish the scale of the activity of English touring companies in Gdańsk in the early seventeenth century.

Limon continued to write articles and books in both English and Polish on the Elizabethan and Jacobean stage throughout his career. His first monograph, Gentleman of a Company: English Players in Central and Eastern Europe, 1590–1660 (1985), expands on his dissertation by not only containing his description of the Fencing School but also describing the route followed by English actors on the Continent in the early seventeenth century and their performances for noble patrons. The following year he published Dangerous Matter: English Drama and Politics, 1623/24 (1986), where he undertakes a textual analysis of five Jacobean plays that he contends were part of an elaborate propaganda campaign intended to promote the views of a particular faction at the court of King James I. In The Masque of Stuart Culture (1990), he analyzes the masque as a genre closely related to court ritual. More recently, he published Szekspir bez cenzury: Erotyczny żart na scenie elżbietańskiej (Shakespeare Uncensored: The Bawdy Joke on the Elizabethan Stage, 2018), a lexicon of Shakespearean jokes that is also a commentary on the history and culture of England at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

By the 1990–91 school year, when my husband and I returned to Poland, Jurek had transitioned from his academic study of Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre to a seemingly quixotic plan: he wanted to reconstruct the Fencing School on its original site. Inspired by the American actor Sam Wanamaker’s efforts to rebuild the Globe Theatre in London, he initiated a similar project in Gdańsk. His first step was to establish a foundation, Fundacja Theatrum Gedanense, whose primary purpose was to build the theatre. Over the years, this foundation also organized academic conferences, sponsored concerts and other artistic events, implemented an educational program for young people, and raised funds from individuals (including Britain’s Prince Charles, who became the Foundation’s patron); corporations; and local, national, and international governmental organizations. In 1993, it also began a Shakespeare festival, at first called the Gdańsk Shakespeare Days, but renamed in 1997 the Gdańsk Shakespeare Festival. The festival has been held annually since then during St. Dominic’s Fair, a traditional early-August festival that has taken place since the Middle Ages in Gdańsk. This is precisely when the English actors would perform in the Fencing School in the early seventeenth century.

The Gdańsk Fencing School, shown on the right, engraving by Peter Willer, 1687.

The foundation and Shakespeare Festival served two functions: they grew support for the reconstruction of the theatre, and they spread knowledge about and familiarity with William Shakespeare and his works in the Gdańsk area. Shakespeare became inextricably associated with Gdańsk. On 12 February 1992, in an article in Gazeta Wyborcza about one of the conferences sponsored by the foundation, the Gdańsk poet Anna Czekanowicz declared, “Jeżeli Szekspir, to jesteśmy w Gdańsku” (If it’s Shakespeare, then we must be in Gdańsk). This became a recurring slogan as more and more Shakespeare festivals were held and the foundation sponsored other events associated with Shakespeare. Limon traveled all over the world, seeking out interesting Shakespeare productions and inviting them to perform at the Festival. Because of bringing these productions to Gdańsk, he learned what directors needed from venues hosting their productions. As a result of this and also of the experience of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, which many directors complained was too limiting to stage plays in, he modified his own ideas about reconstructing the Fencing School.

As early as 1991, Limon consulted with the Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage Conservator, Marcin Gawlicki, to find out if reconstructing the theatre would be possible. Archaeological excavations were undertaken, first between 1997 and 2000, and then again in 2004. During the first excavation, parts of the Fencing School were discovered, but they were interpreted by the archaeologists as the remains of nineteenth-century outbuildings. However, when Gawlicki compared the drawings the archaeologists made with Willer’s print and also with a drawing found in Swedish archives that documented the city’s layout at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, he was able to determine that the wooden structures that the archaeologists had thought were nineteenth-century outbuildings were more likely to have been the remains of the seventeenth-century Fencing School. In 2001, the Theatrum Gedanense foundation obtained rights to the land and commissioned a second excavation. The 2004 excavation, along with dendochronological studies conducted on the wood found at the site, confirmed Gawlicki’s hypothesis. The foundation commissioned him to publish a study that reported on the new archaeological findings and made recommendations about the reconstruction of the theatre.

Gawlicki’s study confirmed the correctness of Limon’s evolving thinking about the undesirability of reconstructing an Elizabethan theatre in Gdańsk in a completely literal way. An international competition soliciting proposals for the reconstruction was announced that same year. The call for proposals specified that the architects had to propose an edifice that would take into account the original dimensions and Fortune Theatre–like structure of the Fencing School, but would also be flexible enough to accommodate productions originally designed for different spaces. Thirty-eight entries were submitted to the competition, and in January 2005, Renato Rizzi, a Venetian architect, was declared the winner. Rizzi’s design from the outside looks nothing like the Fencing School from Peter Willer’s print, but instead, enters into a dialogue with the architecture of the city of the Gdańsk; it is constructed of black brick, echoing the red-brick Gothic churches in the city’s Old Town and the medieval fortifications that surrounded it. Inside, however, the black brick gives way to a light-colored wooden structure, with Elizabethan-style galleries of seats for spectators, a ceiling that can be opened and closed, and the ability to accommodate proscenium, thrust, and in-the-round productions.

In 2008, a new institution, the Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre, was incorporated, and in 2009, the official groundbreaking for the theatre was held. The groundbreaking ceremony was attended by Donald Tusk, then Prime Minster of Poland; the Minister of Culture; and many local dignitaries. It was preceded by an artistic event devised by filmmaker Andrzej Wajda, an honorary patron of the Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre, called Aktorzy przyjechali (The Actors Are Come Hither) in which eighty actors from all over Poland performed scenes from Shakespeare’s plays on twenty-two outdoor stages along the Long Market, the main street in Gdańsk’s Old Town. The spectators—who numbered around ten thousand—could move from stage to stage to watch the performances of the actors, many of whom were film and television stars. As Limon himself wrote in his 2011 article “The City and the ‘Problem’ of Theatre Reconstructions: ‘Shakespearean’ Theatres in London and Gdańsk” for the Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare, “Thus, for one hour the whole city spoke Shakespeare, adding to the narrative that has continued since around 1600, when the first English players came to Gdańsk.”

The 2009 groundbreaking event is just one example of the prodigious feats of organizing and fundraising that Jerzy Limon undertook over the years. Societies of Friends of the Theatrum Gedanese Foundation were started in the United Kingdom and the United States, and fundraising events, including ones that Prince Charles attended in the UK and Barbara Bush attended in the US, were held. A small performance space, the Teatr w Oknie / Two Windows Theatre, was started as a kind of spin-off of the Actors Are Come Hither happening, and continues to be an alternative space for performances during the Shakespeare Festival. In 2010, Limon, along with representatives from the UK, Armenia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Romania, France, Macedonia, and Serbia, founded the European Shakespeare Festivals Network (ESFN), and became its founding chairman. The Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre applied for and received a large grant from the European Union, which enabled it to complete construction. And at last, construction was completed on the magnificent realization of Rizzi’s design, which was also the fulfillment of Limon’s visionary idea to bring Gdańsk’s “golden age”—the Renaissance, when Gdańsk was the largest metropolis in Poland and a multicultural city teaming with tradesmen and traveling artists—back to life. The Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre, the first purpose-built theatre to be constructed in Poland in forty years, opened on 19 September 2014.

One would think that with all the organizational activity involved in being the president of the Theatrum Gedanense Foundation, the director of the Gdańsk Shakespeare Festival, the founding chairman of the ESFN, and the artistic director of the Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre, Jurek would not have had much time left for teaching or writing. In fact, however, until his recent retirement, he taught a full load of courses at the University of Gdańsk, and even established a new department, the Department of Performing Arts, which he ran for three years. He was also an active scholar, and his scholarship evolved over the years from being solely concerned with Shakespearean and Jacobean theatre and drama to being more engaged with questions of the semiotics of theatre. In works such as Między niebem a sceną: Przestrzeń i czas w teatrze (Between Heaven and the Stage: Space and Time in Theatre, 2002), Trzy teatry: scena, telewizja, radio (Three Theatres: The Stage, Television, Radio, 2003), Piąty wymiar teatru (The Fifth Dimension of the Theatre, 2006), and The Chemistry of the Theatre: Performativity of Time (2010), he sought to define the theatrical performance as a communicative act in which fictional characters are created by real actors who create a present time on the stage that is received as a past or future time by an audience inhabiting a different space than the actors. He also sought to distinguish the communicative systems in live theatre from those in theatre presented on television or in radio theatre.

Limon was also active as a translator of dramatic works. Together with his friend, the playwright Władysław Zawistowski, he translated plays by Shakespeare and other Elizabethans from English to Polish, including Antony and Cleopatra and Troilus and Cressida, as well as Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy and Henry Chettle’s Tragedy of Hoffman (which takes place in Gdańsk). He also translated plays by Tom Stoppard, including Arcadia, The Invention of Love, The Real Inspector Hound, and The Artist Descending the Stairs, as well as Stoppard’s screenplay for Shakespeare in Love. His translations of Arcadia and The Invention of Love were performed at the Teatr Wybrzeże in Gdańsk.

Jurek also wrote his own literary works, some of which were novels; others might be more properly classified as creative nonfiction. For example, in Wieloryb (The Whale, 1998), which he wrote under a pseudonym, the “author” structured fictional archival documents into a meditation on human memory that was also a response to the hundreds of archival documents Limon had studied and edited as a theatre historian. (In 2018, this work was adapted for the stage by Romuald Wicza-Pokojski and presented by the director Jacek Głomb at the Miniatura Theatre in Gdańsk.) In Młot na poetów albo Kronika ściętych głów (A Hammer for Poets, or The Chronicle of Beheaded Heads, 2014), he wrote about three real seventeenth-century Polish authors of political pamphlets whose books were publicly burned thanks to the machinations of agents of King James I, whom they had criticized. Limon constructed his nonlinear “chronicle” from commentaries, digressions, and quotations that he had found in his research and regarded this work as a kind of deconstruction of the traditional narrative of history.

Jerzy Limon had retired from teaching, and had announced his retirement as artistic director of the Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre at the time of his last illness. He had been planning to devote himself to his writing now that he would no longer be running the theatre, and we can only mourn those groundbreaking works of criticism and literature that he had not yet created. Nevertheless, he leaves behind several institutions that are firmly established in the cultural and physical landscape of Gdańsk and Europe as a whole. Thanks to him the residents of the Gdańsk area have been able for the last twenty-five years to see Shakespeare productions by the world’s most interesting directors. The Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatre was, under his leadership, constantly inventing new ways to engage with its own community and the world at large. He also leaves behind many friends in the artistic and academic communities in Poland and around the world. Even in the mid-1980s, I had the impression that Jurek knew everyone, and by the end of his life, it seemed as if he really did. I join the directors whose plays were performed in the theatre he built, the Shakespeare scholars, his family, and all the people who came into contact with him over the years in mourning a true visionary and great friend.

Kathleen Cioffi is a theatre historian and drama critic who writes frequently about Polish theatre. She lived for four years in Gdańsk, Poland, where she cofounded Maybe Theatre, a group that performs English-language theatre productions in Gdańsk. She is the author of Alternative Theatre in Poland, 1954–1989 (1996) and the coeditor, with Magda Romanska, of Theatermachine: Tadeusz Kantor in Context (2020).

European Stages, vol. 16, no. 1 (Fall 2021)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Alyssa Hanley, Assistant Managing Editor

Emma Loerick, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berliner Theatertreffen Fights to Survive as Live Theatre Adapts to World Conditions by Steve Earnest

- Cultural Passport for Piatra Neamț Theatre Festival 2021 by Oana Cristea Grigorescu

- We See the Bones Reflected: Luk Perceval’s 3STRS in Warsaw, 2021 by Chris Rzonca

- Festival Grec 2021 by Maria Delgado and Anton Pujol

- Report from London (November – December, 2019) by Dan Venning

- A National Theatre Reopens by Marvin Carlson

- In Memoriam: Mieczysław Janowski, 1935 – 2021 by Dominika Laster

- In Memoriam: Jerzy Limon, 1950–2021 by Kathleen Cioffi

- In Memoriam: Marion Peter Holt

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2021 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2021