London spectators interested in Ibsen had a special treat offered them this September, two of Ibsen’s most popular works revived in highly innovative productions at London’s two most heavily supported theatres, the National and the Lyric Hammersmith. Even Ibsen-starved New Yorkers like myself could manage, as I did, to take in both productions over a week-end trip.

The Lyric Hammersmith Doll’s House was the more radical reworking of the two, though who can say what a “conventional” production of Peer Gynt should look like? This production has attracted special attention because it is the first by a new artistic director, Rachel O’Riordan, clearly one of the rising stars in the contemporary British theatre. O’Riordan is unusual among London artistic directors, not only because she is a woman, but perhaps even more because her training and background does not include such traditional milestones as Oxford, Cambridge or RADA, but was built up in not one but all three of the “other” British autonomous regions—Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. The first company she established was Ransom, in Belfast (where her first major production, Hurricane, toured to Edinburgh, Lodon, and New York in 2004). She then went on to build her reputation as artistic director of the Perth Theatre in Scotland and the Sherman in Wales. It is rather as if a woman who had directed only in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island were appointed artistic director of a major Manhattan house.

O’Riordan herself has spoken of this production as a “statement of intent,” and it is surely a bold and successful one, suggesting a theatre seeking to find a broad social audience, especially including women and non-traditional ethnicities, and concerned with contemporary social and cultural issues. She commissioned one of England’s best known Asian/English playwrights, Tanka Gupta, to create a new adaptation of A Doll’s House, following a formula that Gupta has used with great success in several previous works. Probably the best known of these was her 2017 stage adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, reset in 1861 Calcutta. The production toured Great Britain and was presented in Chicago as well.

Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, adapted by Tanka Gupta, directed by Rachel O’Riordan. Photo: courtesy Lyric Hammersmith.

Gupta has pursued a very similar and equally successful strategy with Ibsen’s play. Her adaptation is set in the same year as Ibsen’s play, 1879, but with the action moved to Calcutta. As she did with the Dickens, Gupta has ingeniously underlined the parallels between the social concerns of both Ibsen and Dickens with wealth, class, status and gender, while adding into the mix the closely related themes of race and colonialism.

When the audience enters, the curtains are open to reveal a handsome design for the cubical interior courtyard house of a Calcutta home in 1879 (scene by Lily Arnold; lighting by Kevin Treacy). The walls are a warm terracotta and the only visible door a solid dark wooden entrance up center, containing the fatal mailbox, but never used until the final scene. Passageways give access to this space on either side, and a balcony surrounds the space at a higher level. Although the actors move frequently and freely about these various spaces, the whole gives a distinct sense of enclosure, the box in which the pampered heroine is contained. The most striking visual element is a huge banana tree growing up from the courtyard floor to open its branches through a square roof opening high above. Nora (in this adaptation the Bengali Niru) hides her forbidden sweets (jalebi) behind the large trunk of this tree, encouraging us to see a connection between them, the tree suggesting a way upward and outward (through an invisible glass ceiling perhaps). At the far left of the balcony, a single musician (Arun Ghost) provides a running musical accompaniment to the action, played on Indian instruments. It was quite effective, but I was a bit troubled by never being sure whether he was supposed to be a diegetic element or not.

Anjana Vasan as Niru dominates the production, despite the fact that she does seem physically almost a doll to Elliot Cowan’s towering Tom Helmer, the Englishman who has married an “Indian skylark.” Cowan emphasizes this quality in their relationship by frequently tossing Niru about or placing her on his knee like a puppet. The physical, gender and financial power relationships, however, are constantly deepened and enriched by social/political ones, those of colonizer and colonized. Tom insists that Niru wear a Sari, and clearly regards her, as England regards India, as a fascinating, if inferior orientalised possession. This constantly opens striking new dimensions, while never undermining the throughline of the original play. For example, Nora’s famous tarantella is here replaced by a classic Indian kathak dance, and the fact that she performs it before a party of Westerners significantly increases the power of Tom’s pleasure in displaying his exotic possession (sound design by Gregory Clark).

Although the Tom/Niru relationship remains at the heart of the play, each of the other characters naturally takes on new qualities as a result of the shift in background culture. Perhaps the most distinctive change occurs to Dr. Rank, not in his dark cynicism, his suppressed love for Niru, or his wonderfully theatrical exit, but in the fact that his cynicism here is focused upon the uselessness and destructiveness of colonialism in general and the occupation of India in particular. Consider one of the few substantial additions to the text: during Dr. Rank’s first visit to Tom, the two have an extended and sharp, but friendly, discussion of colonialism, with Tom stoutly defending the Raj and its colonializing mission of bringing Western culture and civilization to what he calls “these barbarians.” Once again, the use of colonialism to provide an underpinning for Tom’s relation to his Indian wife is highly effective.

Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, adapted by Tanka Gupta, directed by Rachel O’Riordan. Photo: courtesy Lyric Hammersmith.

Krogstad here becomes the Indian clerk Kaushik Das (Assad Zaman), whose loss of his job working for Tom in the tax office threatens to throw him out among the unemployed masses of Calcutta. Niru’s female confidante, the widowed Mrs. Lahri (Tripti Tripuraneni), is less desperate but also caught in the trap of lacking a position in this rigidly controlled society. Niru has kept her nurse (Arinder Sadhra) to take care of the children, although Tom finds the nurse’s peasant ways, such as her habit of shouting for Niru, a regular source of irritation. The children are never seen, although their Christmas stockings are hung, along with other very modest seasonal decorations, on the balcony for the second act.

When Niru makes her final exit, she goes out through the heavy dark wooden upstage doors, a dominant element in the set never used until this moment. She leaves the door ajar, however, and there is no final slam here or offstage. Perhaps O’Riordan wants to suggest that Tom may in fact also go through that door, an intriguing post colonial suggestion.

Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, adapted by David Hare, directed by Jonathan Kent. Photo: National Theatre.

If A Doll’s House at the Lyric Hammersmith brings attention to major rising talents in the London theatre, Peter Gynt at the National showcases three of the current leading figures of the British stage—director Jonathan Kent, playwright/adaptor David Hare and actor James McArdle. The three were last teamed together in 2016 at the National for the monumental Young Chekhov Cycle, combining productions of Ivanov, Platonov, and The Seagull.

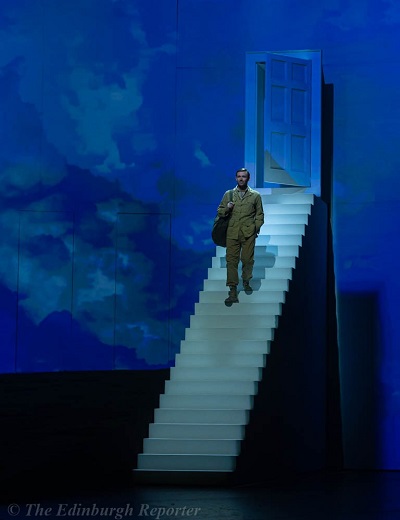

Designer Richard Hudson has divided the immense Olivier stage more or less in half, with the left side always open to view, and usually fairly empty of scenic embellishment, but with an odd, spongy floor from which characters can emerge rather like moles (the Bøyg does so, for example). A dark curtain is often drawn across the right side, to be pulled back to reveal a series of elaborate but fragmentary settings—the country wedding celebration, taking place on a crowded and festively decorated wagon, or the Troll king’s court, gathered around a candelabra-lit high table suggestive of dinner at Hogwarts, but raked at a bizarre angle toward the audience. Behind these spaces, a vast cyclorama provides a screen for a constant play of empyrean effects—swirling clouds, storms, azure desert skies, and occasionally blank walls. Seemingly suspended high up on this background is an isolated door, which opens to reveal Peter in silhouette as the play begins. A set of stairs comes forward beneath the door, allowing him to descend to the stage and to approach his mother’s small hut which stands in the open area to the left. No one uses these stairs or this door but Peter, and it provides one of many suggestions that he can move through dimensions of imagination unknown to the other characters.

The opening scene suggests the approach of the whole. The relationship between Peter (McArdle) and his mother (Ann Louise Ross), and indeed the rhetorical shape of their opening scene in fact, follows Ibsen closely, but all the details have changed. Ibsen’s Norway has become Scotland, Peter a very Scottish yarn-spinner carried along on a sea of words. The reindeer has gone, replaced by Peter’s recounting of his glorious deeds in the war from which he has just returned, but when Peter lifts his mother to her own roof and runs off to interrupt the local wedding, we are clearly back in the Ibsen pattern of action.

Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, adapted by David Hare, directed by Jonathan Kent. Photo: National Theatre.

A number of commentators on Ibsen’s play, trying to find some grounding in reality, have suggested that when Peer falls in the mountains and hits his head in the first act, this begins a series of imaginary events. The problem with this interpretation is that while it gives a nice explanation for the Troll scenes, which follow shortly thereafter, Ibsen provides no clear event that can mark Peer’s return to consciousness. For the rest of the play, we go back and forth between scenes which seem part of a fevered nightmare (the madhouse, the threadballs, the button molder) and others which seem clearly of a piece with the more realistic opening (the encounter with Solveig, the death of Peer’s mother). There are even scenes that seem to mix both levels of reality—as when Peer returns to Solveig’s hut in the woods, seemingly in the realist vein, but is then driven away by the appearance of figures from the Troll world, the Troll king’s daughter (Tamsin Carroll) and her bastard son (Sonnyboy Skelton), who in this production is the only Troll to support a second head.

Kent’s solution to the transition from the world of humans to that of the Trolls is bold but ultimately unclear. Instead of hitting his head on a rock, Peter runs downstage and into a door, which is a twin to the air-borne one from which he entered. He collapses there and lies inert for the entire Troll sequence, which follows. We soon discover that by a clever bit of stage trickery, the body which appears to be that of McArdle is a double, and the real McArdle plays out the Troll scenes upstage of the inert figure. Kent makes ingenious use of this conceit when, as the Troll scene becomes more nightmarish and dangerous for the hero, he becomes aware of his unconscious self and in a true nightmare scenario, punches and shakes the figure, trying to awaken him. At last the ringing of the church bells achieves this goal-the Trolls disappear behind their curtain and the Peter double, I assume, into an onstage trap. McArdle is left to encounter the Boyg, whose head and shoulders emerge from the porous landscape on the left side of the stage. The role is a striking cameo for the noted disabled British/Jordanian actor Nabil Shaban. Before leaving the trolls, I should note that they are less physically grotesque than is often the case, marked largely by their sporting of pig snouts. As for their motto, Hare has found one of the best translations I have encountered: “To thyself be true—and to hell with everyone else.”

Agatha’s death scene, like the opening scene, closely follows Ibsen’s action while altering various details. Peter converts Agatha’s pallet not into a sled but into a spaceship, festooning it with lights from a small Christmas tree which is the only other item in the setting. In this ship, he takes her to meet St. Peter and to gain her admittance to heaven. At the end of this scene, and of the first act, the floating door opens, the approach stairs roll out, and Peter leaves as he entered, through that celestial portal which now, thanks to the previous scene, strongly suggests his entering his own spaceship.

Much of Peter’s international traveling is depicted with simple colorful settings, many backed by large and rather tacky postcards of the various locations. The scene with other international moguls on the coast of Morocco is given a smart updating, set at a table beside a Trumpian golf course, with Peter shocking his companions not by furnishing arms to the Turks, as in the original, but to the Iranians, along with a nicely cynical disquisition upon the Shia and Sunni divide. He leaves behind his computer, which his companions hack (guessing the password “Iammyself,” and with a few keystrokes, wipe out his financial empire. Clearly Hare saw this as an effective updating, but he loses the wonderful moment of the divine destruction of the confiscated yacht and Peer’s great and significant line “But economical—that he’s not.” The rival entrepreneurs not only survive, but reappear in a party scene Hare has added (to very little advantage) taking place in the ballroom of a modern international hotel. With them are other members of the exploiting class, including Arab sheiks and even a hyena from the previous desert scene. Peter crashes the party, in his desert-assumed role of the prophet, and at first makes a profound impression, but his former companions reveal his disguise, and he is driven away by the outraged capitalists.

Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, adapted by David Hare, directed by Jonathan Kent. Photo: National Theatre.

This is one of the few sequences, fortunately, that Hare has added to Ibsen’s already sprawling structure, but on the other hand he has retained several of which I am quite fond and which are often cut. One of these is the threadball scene, which Hare keeps largely intact, the various visionary elements played by ghostly figures, half human, half vegetative. Another is the scene of the young man who cuts off his finger, and the subsequent scene of his funeral. As with the unconscious body in the Troll scene, Kent has created a powerful visual image out of this sequence. This is the open grave of the young man, downstage center in the same spot where the unconscious Peter lay earlier. The grave remains open for the remainder of the play, and as Peter grows nearer his final judgment, becomes more and more central to the action. Peter sits with his legs in the grave and peels the famous onion into it, and at the conclusion, the still youthful Sabine (Anya Chalotra) sits there beside him, and a final tableau is created when the aged Peter lies across her lap in a kind of Pieta (a visual reference [unconscious?] to the almost identical final image in Peter Stein’s famous 1971 production of Ibsen’s play).

Given the huge casting demands of the play, Kent has not employed much doubling. Fewer than half of his twenty-five member cast play more than one part. The woman in Green and Anitra, as is usually done, are played by the same actress, Tamsin Carroll, and the same three actresses (Lauren Ellis-Steele, Hannah Visocchi, and Dani Heron) play both the desert sirens and the Herding girls in the mountains (here rather inexplicably converted into singing American cowgirls). The madmen in Cairo (Martin Quinn, Jatinder Singh Randhawa and Ryan Hunter) play no other roles but are costumed and made up (despite their different heights) as doubles of Peter. This builds to one of the production’s most striking visual effects. As the madhouse begins to break into chaos, the right side curtain opens to reveal what seems to be a vast hall filled with hundreds of copies of Peter. McArdle himself climbs to the top of an improvised pyramid of tables and chairs hastily erected downstage of this mass, and cries out in horror in a stunning downlight as the sequence ends.

London reviewers were somewhat mixed in their reactions. All had warm praise for the remarkable performance of McArdle, and for the power and resilience he continued to draw upon even as he clearly aged. The range and the depth of his supporting cast were also generally praised, as were the colorful and ingenious settings by Richard Hudson. Opinion was more divided on Kent, Hare, and indeed on Ibsen himself. Most praised Hare’s reworkings in general, but some found them occasionally too clever and self-conscious. Opinions were similar regarding Kent’s revisualizations of various scenes. A few critics blamed Ibsen, for creating a work so sprawling and unconventional that even the best efforts could not make it an evening of truly engaging theatre. My own reactions were distinctly more positive than not. I found the acting, especially that of McArdle, truly impressive. As for the adaptation of Kent and Hare, I found it on the whole much more successful than not. A few innovations did not work very well, but on the whole, both adaptor and director found striking new ways of making the play’s most important points. It is a very welcome revival of this challenging work at one of the world’s great theatres.

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is Theatre & Islam Macmillan, Red Globe, 2019.

European Stages, vol. 14, no. 1 (Fall 2019)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Stephen Cedars, Assistant Managing Editor

Dohyun Gracia Shin, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 73rd Avignon Festival, July 4-23, 2019 : Odysseys, past, present and future by Philippa Wehle.

- Ibsen in London by Marvin Carlson.

- Report from London (November – December, 2018) by Dan Venning.

- It’s All in the Wrist: How Nina Conti Faces Off with Reality by Katy Houska.

- Staging Trauma: A Review of Bryony Kimmings’s I’m a Phoenix, Bitch by Rachel Anderson-Rabern.

- Difficult Pasts and Revivals: Madrid Theatre Summer 2019 by Maria M. Delgado.

- Cultural Diversity in the Kunstenfestivaldesarts (Brussels) 2019 by Manuel García Martínez.

- Tampere Theatre Festival: Progressing Society by Pirkko Koski.

- Nasza Klasa in Georgia by Mikheil Nishnianidze.

- Young and Critical Voices of Turkey I: “Theatre helps us to hear each other.” A Conversation with Irem Aydın by Eylem Ejder.

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019