In Vienna in March of 2018 I was able to attend an imaginative revival of a modern German classic, the premiere of an important new international work, and the final production of one of the best-known of modern German theatre artists, Claus Peymann. Clearly the Peymann production was the most newsworthy of these offerings. Peymann emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as one of Germany’s most innovative and imaginative young directors, and his prominence continued in his directorship of the theatres in Stuttgart and Bochum during the following decade. Between 1986 and 1999 he directed the national Burgtheater in Vienna, and although often engaged in controversy, was generally considered then at the peak of his career. His subsequent direction of the Berliner Ensemble, which concluded in 2017, was generally considered much less distinguished, and it is hardly surprising that he should return to the Burgtheater, scene of some of his greatest triumphs, to present what he has announced as his final work, Ionesco’s The Chairs.

The Chairs. Photo Credit: Georg Soulek.

While the venue is understandable, the selection of work is much less so. One might have expected Peymann’s final offering to be something from Peter Handke or Thomas Bernhard, the two authors with whom he has been most associated throughout his career, while no Ionesco piece is among his remembered productions. Perhaps he wished to return to memories of his first directing work in the student theatre of the 1960s, when Ionesco was a familiar figure. In any case, whatever the production, Peymann still has many loyal followers in Vienna, and the announcement that the Burgtheater would be the site of his final production aroused considerable interest.

The preparation of the production did not go well. Maria Happel, who plays the Old Lady, broke her foot and the opening had to be reschedule. Then in the final weeks, Peymann suffered so serious a viral infection that Leander Haussmann, who has occasionally directed at the Burgtheater, took over the production. The result was a production with not clear shape or style, although the actors settled into routines familiar to both of them and were enthusiastically received by the overflow audience. This was however after a troubled start that perfectly suited the production’s difficult coming into being. As the last audience members were taking their seats a thin black curtain hiding the set came loose from part of its veiling mooring and floated downward. Frantic backstage workers climbed out onto balconies and up ladders to resolve the problem. Finally the problem was solved and the setting (by Gilles Taschet) officially revealed—a dark minimalist chamber with two black converging walls, each containing row of doors and a tall ladder. Two black chairs downstage and a gilded chandelier with a few colored streamers hanging from it complete the setting. The comic routines of the two main actors are varied and engaging, especially when they interact in various tonalities with the different guests, Happel ranging from a doting wife to a far too old Cancan dancer. All the while the stage fills with chairs, carried through the doors by the old woman and by another actress dressed as her double, making her appear to move backstage from one side to the other with lightning speed.

The arrival of the Emperor involves a major, and to my mind unsuccessful break in the style. His chair, actually a crude throne, is not brought in like the others but lowered on ropes from a trap door in the ceiling to an accompanying blast of Leonard Cohen’s “Show me the place where you want your slave to go.” The orator sequence is even more unconventional and bizarre. The orator (Mavie Hörbinger) appears upstage out of a billowing grey cloud and then moves all over the stage, writing inexplicable messages on all surfaces, the walls, the floor, the doors, the chairs. When the old couple commit suicide together, pink and blue balloons emerge from the smoke and ascend to the ceiling. At least one critic identified these as the souls of the couple, which seems as reasonable and banal an interpretation as any. Which director conceived this ending was impossible to discover, though Haussmann claimed to have made no major changes. He did appear onstage among the actors for the obligatory repeated curtain calls however, sporting black T-shirt, with PEYMANN in large white letters on it, thus creating an image that will probably remain with me long after the rest of this rather undistinguished staging has faded from my memory.

Chairs. Photo Credit: Georg Soulek.

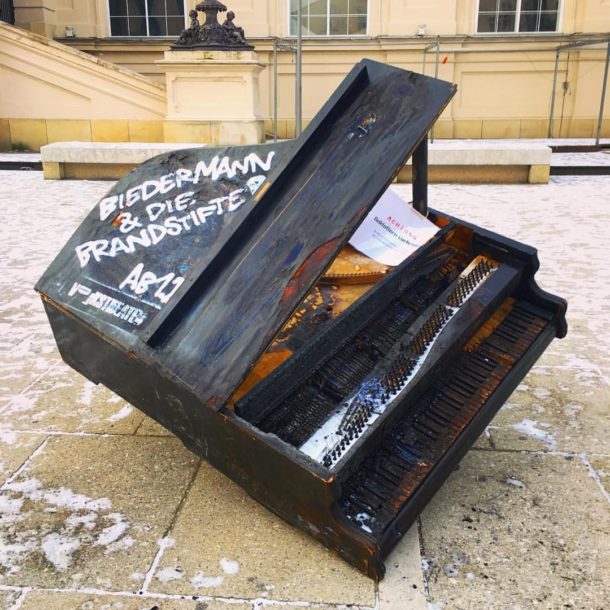

Another revival of a modern classic was being offered at the Vienna Volkstheater, Max Frisch’s modern allegory Biedermann and the Firebugs. The theatre made a considerable effort to attract attention to this now somewhat dated piece with a rather overly obvious moral. Huge fires burned in front of the theatre, and firelike spotlights shot from its roof into the sky. In preparation for the premiere, the theatre worked with Vienna artists and advertisers to place six installations in various prominent locations around the city. They at first appeared to be vandalized and burned objects—a grand piano, a delivery van and so on—but a second look revealed the name of the upcoming production painted on their damaged surfaces.

Patric Butterer piano. Photo Credit: Picdeer.

Truck ad for Biedermann. Photo Credit: Picdeer.

One might say that visiting Hungarian director Viktor Bodó, well known for his unconventional stagings, similarly vandalized the Fritsch original, turning a rather simple-minded and cartoonish piece into an evening of freewheeling slapstick. Within a greeting-card like artificial bourgeois setting designed by Juli Baláz the hopelessly naïve Beidermanns (Günter Franz Meier and Steffi Krautz), look on helplessly as the arsonists he has let into his home (Thoma Frank and Gäbor Biedermann) create increasing danger and mayhem, including even the slasher-style murder of the visiting widow Knechtling (Claudia Sabitzer), indicated by her blood splashed on the upstage side of the glass pocket doors. Film and pop culture references abound, and were much enjoyed by the predominantly youthful audience. Stefan Suske and Nils Hohenhövel provide a chorus in the form of two appropriately garbed firemen whose Keystone cops routines prove as effective in stopping the arsonists as the original cops were in preventing violence and mayhem. Far from appearing as a cautionary tale, the evening came across as a celebration of pure farce, and as such it was very effective.

Biedermann. Photo Credit: Volkstheater.

The third production I attended, also at the Volkstheater, struck a very different note. This was a new drama, Rojava, by the emerging young Austria/Kurdish dramatist, Ibrahim Amir. I was particularly interested in seeing this piece, since early in 2018 I was able to see this author’s highly successful previous work, Homohalal (See “Report from Vienna,” European Stages, Spring, 2018). In fact, Homohalal was originally planned to premiere at the Volkstheater, but its darkly comedic dystopian exploration of the immigration crisis was considered by the theatre directors too inflammatory and only after a successful opening in Dresden did it appear in Vienna, not at the Volkstheater, but at the smaller and much more experimental Werk X. Thus Rojava is in fact his Volkstheater premiere, commissioned by that theatre after the success of Homohalal. The new play engages the experience of the author and the current situation in the Middle East much more directly, but it lacks much of the humor and irony of the earlier piece, and most reviewers, myself included, found it rather heavy-handed and not really successful in making the emotional appeal it clearly sought. Indeed the most emotionally effective part of the play was the musical accompaniment provided by five onstage musicians, presenting effective exotic melodies created by the composer/director Sandy Lopićić. The play focuses upon two young men, both reflecting aspects of their bicultural creator. Michael (Peter Fasching) is an idealistic young Viennese who travels to the Syrian-Kurdish region of Rojava to support what he sees is a struggle for a democratic utopia. There he meets a Kurdish counterpart, Alan (Luka Vlatković) who is exhausted by death and destruction and dreams only of escaping to somewhere like Vienna. A certain romantic interest is provided by Michael’s attraction to Hevin, a fighter in the woman’s defense league (Isabella Kröll) and Alan’s only surviving relative, a blind cousin named Kaua (Sebstian Pass) attempts to deepen the action with Tieresias-like prophecies. Pass does project an intriguing other-worldly air, but Körbll is not really much developed beyond feminist slogans, and ultimately characters, like the central young men, do not really achieve much depth. Clearly the author’s dramatic talent lies more in the realm of dark comedy than in vaguely symbolic realism. The effective setting by Vibeke Andersen creates on one side of the theatre’s large revolving stage, the warmly overstuffed upper middle class Viennese home of Michael’s mother, and on the other the smoking ruins of the Syrian war zone.

Rojava. Volkstheater. Photo Credits: www.lupispuma.com

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is a theatrical autobiography, 10,000 Nights, University of Michigan, 2017.

European Stages, vol. 13, no. 1 (Spring 2019)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Introductory Note by Kalina Stefanova.

- “Andrzej Tadeusz Wirth (1927 – 2019) – White on White” by Krystyna Illakowicz.

- Lithuanian Marriage in Warsaw or The Last Production of the Great Eimuntas Nekrošius by Artur Duda.

- “My, Żydzi polscy [We, Polish Jews]”: A Review of Notes from Exile by Dominika Laster.

- A Report on the State of Our Society, According to Jiří Havelk in The Fellowship of Owners at VOSTO5, Prague, and Elites, at the Slovak National Theater, Bratislava by Jitka Šotkovská.

- About Life as Something We Borrow. On the Stages of Pilsen (In the 26 th edition of the International Theatre Festival There) by Kalina Stefanova.

- Redesigning Multiculturalism or Japanese Encounters in Sibiu, Romani, The Scarlet Princess, written and directed by Silviu Purcărete, inspired by Tsuruya Namboku IV’s Sakura Hime Azuma Bunshô by Ion M. Tomuș.

- About Globalization: A “Venice Merchant” on Wall Street, at the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj in Romania by Maria Zărnescu.

- The Patriots, Mary Stuart and Ivanov and the Rise of the Drama Ensemble of the National Theatre in Belgrade by Ksenija Radulović.

- The Unseen Theatre Company or How to See Beyond the Visible: The Shadow of My Soul and the Theatre of Velimir Velev by Gergana Traykova.

- Multilingual Pirandello, Understandable to Everyone: The Mountain Giants at the Croatian National Theatre “Ivan pl. Zajc”, Rijeka by Kim Cuculić.

- The return of the repressed: the ghosts of the past haunt Barcelona’s stages by Maria M. Delgado.

- A poetics of memory on the Madrid stage (2018) by Maria M. Delgado.

- The Danish National Theatre System and the Danish National School of Performing Arts: December in Copenhagen 2018 by Steve Earnest.

- Towards a Theatre of Monodrama in Turkey 1 by Eylem Ejder.

- Where Is Truth? Justiz by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at the Schauspielhaus Zürich by Katrin Hilbe.

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson.

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019