On the tenth day of each month, manifestations and counter-manifestations are organized in Poland commemorating the 2010 plane crash in Smolensk, in which Polish President Lech Kaczyński and over 90 other persons accompanying him died. Other counter-manifestations and marches such as the Black Protest or National Women’s Strike take place in larger and smaller towns, defending democracy, women’s rights, and the freedom of speech. Protesters also include artists creating performances and other artistic actions against unconstitutional government policies. In 2017, Warsaw theatre audiences went to the streets to defend the Powszechny Theatre, protesting against the occupation of the theatre by the members of religious and nationalist groups obstructing the performance of Klątwa (The Curse) by Stanisław Wyspiański, directed by Oliver Frljić. Protests also erupted in Wrocław (Teatr Polski) and in in Bydgoszcz. Politics became the main theme and inspiration for the most important theatre performances of the past season.

Two premieres from the spring of 2016, All about My Mother (Wszystko o mojej matce) by Tomasz Śpiewak and Robert Robur, a performance based on the last, unfinished book by Mirosław Nahacz, set the tone of 2016–17 season. The first one was directed by Michał Borczuch and staged by the Kraków Łaźnia Nowa Theater; the second was directed by Krzysztof Garbaczewski and showed by TR Warszawa. These productions proposed two very divergent perceptions of the condition of modern society, susceptible to control and manipulation, whose members are afraid to unveil their “true selves,” demonstrating problems with interpersonal relationships and the expression of emotions.

All about My Mother. Photo: Klaudyna Schubert.

The personal experiences of the director, Michał Borczuch, and the actor, Krzysztof Zarzecki, inspired the performance of All about My Mother. Both men lost their mothers in their youth and tried to find a way to face their most intimate memories and speak about their experiences of loss, and deformation of memories. Borczuch’s narrative consists of broken and unrelated images, such as the scene opening the performance in the Miraculum perfume factory (Kraków) where his mother worked. The words that she and her companions say overlap, interweave, drown and loop, creating a cacophony of sounds from which no single story can be extracted. Only elusive fragments remain, stored by the child’s memory, such as the smell of perfume, or a favorite color or make-up applied by his ill mother.

All about My Mother. Photo: Klaudyna Schubert.

Borczuch’s memories of his mother are combined with scenes from his childhood; her illness overlaps with the image of the Chernobyl disaster, the memories of the time spent together invoke a picture of the flat in which he spent his childhood. Today it is easier for him to remember where the kitchen or the bathroom were than what his mother liked to wear or how she moved or spoke. If the only proof of his mother’s existence, as the director says, is her grave at the Rakowicki Cemetery, then the rest must be a figment of fantasy created by a deceptive memory.

The second part of the performance is built around Krzysztof Zarzecki’s story, whose mother died when he was taking his secondary school final examinations. His memories are much clearer than Borczuch’s, but instead of focusing on a biography, the director concentrates on issue of communicating extremely subjective experiences in the theatre and the role of the actor in this process.

All about My Mother. Photo: Klaudyna Schubert.

The actresses in All about My Mother—Dominika Biernat, Iwona Budner, Monika Niemczyk, Halina Rasiakówna, Ewelina Żak, and Marta Ojrzyńska—take on the roles of several characters (as in Pedro Almodóvar’s film All about My Mother that inspired the performance), exploring the limits of what can be shown in the theatre and creating very intimate portraits on stage. The projected image of Ojrzyńska during her pregnancy highlighted her process of maturation and preparation for childbirth. Together with the director and the playwright, the actresses were asked to seek the boundaries of radical privacy and intimacy through their performance. And indeed, their acting probed their emotional limits in relation to themselves and all the other people involved in the production—including the director and the author. Their emotional clashes and exchanges soon become the main subject of a performance that abandons its initial theme (relating to the mothers), in favor of a much more interesting reflection on the nature of acting and the theatre itself. It examined the mechanisms that govern memory and expression of emotions, often too private and too intimate to talk about openly.

Robert Robur. Photo: TR Warsaw.

Emotion, and the control thereof, were also themes of Robert Robur by Mirosław Nahacz, a novel adapted for stage by TR Warszawa and directed by Krzysztof Garbaczewski. The text ponders the creation of an alternative, virtual reality that not only affects the real, but also creates the possibility of controlling society and inspiring individuals to struggle against the system. Like previous performances by Garbaczewski, the action of Robert Robur takes place simultaneously on the stage and on the screen in the form of a huge eye, which constitutes a dominant feature of the stage design. The audience follows a video by Robert Mleczko in the style of B-class live-action cinema, created in front of the spectators, backstage, and in the theatre corridors. Actors smoothly come out of the camera’s frame, appear on stage, and “walk” back into the very center of an alternative reality, increasingly intertwined and blending with the real one.

The book by Nahacz, which was published in 2009, after his suicide, takes place in a future where the fiction created by the media, and especially by television, has completely supplanted reality. Every day, every resident of the City of Light watches the series The Sound and the Fury, written by Robert Robur. This series not only creates an alternative world, but also influences the spectators; it acts as a drug controlling every aspect of their life. Robert Robur, constantly monitored by a 360° video camera following him, traverses theatre corridors with a keyboard hanging over his shoulders. While moving through these spaces, or rather trying to escape, he slowly discovers that everything that surrounds him is fiction. Every wall, every piece of furniture, every landscape is just a decoration that he can change by entering the appropriate computer command and making changes to the script he is writing. He is like a video game character who progresses into higher and more complex stages of a game.

Robert Robur. Photo: TR Warsaw.

Robur’s role was initially given to one actor—Dawid Ogrodnik, but just before the premiere the director decided to have two actors enact him. Paweł Smagała manifested Robur’s body and Justyna Wasilewska, from off stage, gave him voice. That decision made Robur’s character even more broken, unreal, lost not only in the world surrounding him, but also in his own body of undetermined gender. The movements of his lips did not synchronize with the voice, which only intensified the impression of gradual disintegration. It was as if the commands he typed on his keyboard not only changed the fictional reality in which he moved, but also made his insides crack. No wonder that Robur, like other characters of the performance, over and over again asks the question: “Is it really so?” Is it true what he sees and what he feels? What is he attending? Is what he does and what he says real? Does he participate in this? Is he responsible for subsequent events, or is his voice already “disconnected” from himself and imprisoned in virtual reality, in a Matrix, from which it is impossible to escape and in which each subsequent movement is carefully planned and programmed?

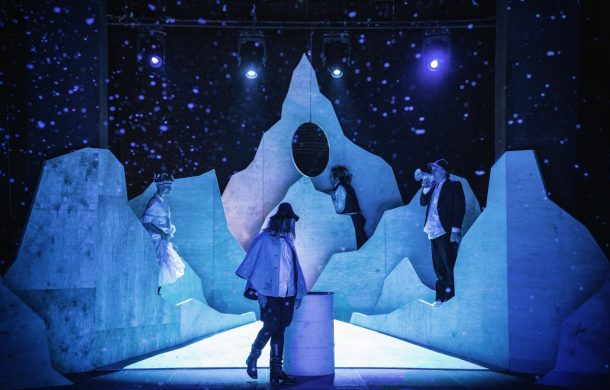

The final part of the performance makes him crack even more. The third act transfers spectators from the claustrophobic corridors to Lemkivshchyna (Lemko’s land), cut out from cardboard and flooded by blue light. After the intermission, the actors greet the spectators returning to their seats with: “Go away! You bring us evil!”, as if they sensed the end of their old world. Or maybe they feel that their existence is just another scene in Robert Robur’s memory, and that the whole affair is invented by the omnipotent producer of the The Sound and the Fury series, Matheo DeZi (Cezary Kosiński). And if their world really did not exist, would Robur’s rebellion and his attempt to escape have any chance of success? Or maybe his battle with the system is doomed to fail, and his life will end when his power, foreseen by the game in which he participates, expires. Garbaczewski does not give clear answers, yet he shows how deeply we might enter into the virtual world, incapable of imagining life without it. Would not we be lost like Robur if one day we were caught up in a parallel reality without the internet, television and any other media?

Triumph of the Will. Photo: Krzystof Kalinowsky.

To such reality, cut off from the outside world, have come the castaway heroes of Triumf woli (Triumph of the Will) by Paweł Demirski, directed by Monika Strzępka, that opened on January 31, 2016. During the creation of that performance, theatre and politics clashed again. Half a year before the premiere, theatre circles focused primarily on the conflict at the Polski Theater in Wrocław in 2016 caused by the appointment of the new pro-government director, Cezary Morawski who laid off many actors. In protest, Krystian Lupa suspended the rehearsals of Proces (Process) by Franz Kafka and many actors and directors protested by taping their mouths with black tape. Their gesture was quickly picked up by actors in other parts of Poland, to express their solidarity with the Polski Theater. Further dismissals and subsequent closing of productions increased the tensions and such artists as Peter Brook and Isabelle Huppert joined the protest.

Out of these protests a new theatre, the Polski Theatre in the Underground, was born. It gathered the actors dismissed by Morawski and supporters from other theaters across Poland. On January 6, 2017, the Polski Theater in the Underground celebrated the 71st anniversary of the Polski Theater with So-Called Humanity Gone Mad (Tak zwana ludzkość w obłędzie ) based on Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz’s text and directed by Krzysztof Garbaczewski.

Triumph of the Will. Photo: Krzystof Kalinowsky.

Soon the Polish theatre magazine Dialog awarded a Konstanty Puzyna Prize known as Puzyna’s Pebble (Kamyk Puzyny) “to actresses, actors and audience of the Polski Theater in Wrocław protesting in the name of the artistic values developed in recent years and destroyed due to erroneous administrative decisions” (Dialog 2017, no. 4). The conflict around the Theatre continues, and the July 2017 premiere of the Polski Theater in the Underground entitled Marzyciele (The Dreamers) presented a playful vision of a new theatre uniting the minister of culture, the whole government, the city, the region and the province, and even “over-” and “under-” ground ensembles of the Polski Theater thus creating what Sebastian Majewski the director of that piece called an “enchanted reality.”

Similarly, Paweł Demirski and Monika Strzępka decided to create an “enchanted reality” in the spectacle Triumph of the Will (Triumf woli). According to them, in the present political climate nothing holds, and it is impossible to act according to traditional forms. They have had enough of protests, complaining, and depressing news. That is why their heroes are winners, the stories they talk about, as well as the encounters and struggles with adversity in their performances take on a light cabaret form and assume an uplifting tone.

Spectators entering the auditorium go through a squealing safety gate, associated with airports, courts, and other offices, and above all, with the growing fear about security in recent years as the live coverage of terrorist attacks floods the internet, television and other media in every corner of the world. This is why, when a moment later the gate is forced open by the figure of William Shakespeare (Krzysztof Zawadzki), and Prospero’s words from The Tempest lead to a catastrophe with castaways appearing on an island, it seems that in a while we will see yet another story devoid of hope, criticizing our current reality. Hostile heroes appear on the sand, among the scattered seats, boxes and suitcases that make up the set. It is hard to believe that they will ever be able to communicate with one another; their words are full of scathing skepticism and poorly hidden aggression. And when some characters come close to breakdown, and the remaining ones feel as if they are about to fight, the performance departs from its original, pessimistic course and starts to build a “brave new world,” filled with optimism.

Triumph of the Will. Photo: Krzystof Kalinowsky.

New characters appear on the stage—winners, pioneers, heroes who changed their world in some way. Among them is Kathrine Switzer (performed by Dorota Segda), the first woman to run the marathon in Boston in 1967, hiding her sex under the pseudonym K.V. Her feat led to the official admission of women to participate in this event, and later to include women marathon runners in the program of the Olympic Games. There is also Rachel Carson (Dorota Pomykała), an ecologist protesting against large corporations using pesticides in the food production process. There is a Samoa football team represented by Małgorzata Zawadzka who tries to score the first goal after a 0:31 loss to Australia. There is also Dashrath Manjhi, called “Mountain Man,” who for 22 years, using a pickaxe, created a path to shorten the way connecting his village to the nearest hospital. There are finally “proud and furious” miners (Juliusz Chrząstowski and Michał Majnicz) along with their gay supporters (played by Krystian Durman), whose story was inspired by the 2014 movie Pride about a Welsh miners’ strike supported by gays and lesbians who united against Margaret Thatcher’s policies. The song There Is Power in a Union sang by them becomes a kind of the anthem for the whole spectacle, and a message about the power of the stage community.

The action of the play moves in time and in space, grows and becomes more complex. It seems to be written impromptu, on the spot, by the occasionally appearing on stage of an increasignly drunken Shakespeare, who instead of speaking his own lines uses Christopher Marlow’s or Stanislaw Wyspiański’s texts. The multiplicity of themes and heroes with the simultaneous repetition of the pattern according to which subsequent stories are constructed, make us perceive Triumph of the Will as a multi-voiced narrative about building a united community, not in opposition to something or someone, but through inspiration by the positive accomplishments of its members.

After almost four hours spent with the characters of Triumph of the Will and the final singing together of There Is Power in a Union, the audience leaving the theatre could for a moment feel a part of the “positive community” created on the stage. Similarly, in Bydgoszcz, as Szymon Kazimierczak states, “the performance of Żony stanu by Wiktor Rubin and Jolanta Janiczak, tests how much theater can unite the audience in the gesture of protest.”

Stateswomen. Photo: Monika Stolarska.

Inspiration for the Żony stanu, dziwki rewolucji, a może i uczone białogłowy (Stateswomen, Sluts of Revolution, or the Learned Ladies), which opened a few weeks after the National Women’s Strike (March 2017), was the history of Théroigne de Méricourt (Sonia Roszczuk), who fought for women’s rights during the French Revolution. Her name, unlike the names of Danton or Robespierre, is not celebrated in history books today—already during the Revolution her ideas were too radical. It was not only revolutionary leaders, but also women who, during one of her speeches, attacked, barred, severely beat her, and rejected her ideas. Her political commitment was treated as a manifestation of madness, and she was shut up at Salpêtrière Hospital, where she died in 1817.

The author of the play, Jolanta Janiczak, and the director Wiktor Rubin once again in their career have taken on the topic of forgotten female heroes, of “women involved in history.” Their earlier trilogy, produced in the Żeromski Theatre in Kielce, portrayed the fate of the Queen Joanna of Castile (Joanna Szalona; Królowa, Joanna the Mad, the Queen, 2011), Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia (Caryca Katarzyna, 2013) and Elisabeth Batory (Hrabina Batory, Countess Batory, 2015). In Bydgoszcz, next to Théroigne de Méricourt, Olympe de Gouges, who in 1791 proclaimed the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, was also on stage demanding equal rights for women and, among others, granting women the right to education. For her ideas and criticism directed against Robespierre’s government, she was guillotined two years later.

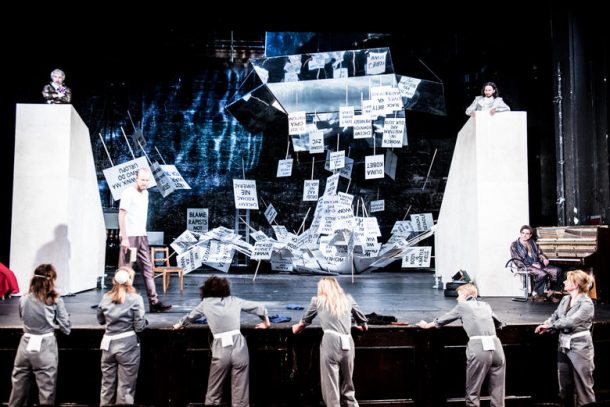

Stateswomen. Photo: Monika Stolarska.

These two characters were referred to by the creators as symbols of female resistance and placed in confrontation with the male characters of Dante (Marcin Zawodziński) and Robespierre (Roland Nowak), who personified masculine force, power and domination. Men give speeches standing on high podiums on both sides of the stage. They are extremely self-confident, neatly dressed and made up, using studied poses—neither Théroigne de Méricourt, nor Olympe de Gouges, or any other women accompanying them, are able to intimidate them. “I can’t breathe because of these menstrual affects” says Dante at one point, evoking the still surprisingly alive stereotype of a hysterical woman, possessed by female hormones, incapable of rational thinking and therefore not to be treated seriously. While the leaders of the revolution are standing on their podiums, watching women from above (literally and figuratively), actresses, dressed in casual working overalls, endeavor to convince and attract the audience to their play.

During almost the whole performance the house lights are on, and six actresses Beata Bandurska, Magdalena Celmer, Martyna Peszko, Sonia Roszczuk, Małgorzata Trofimiuk and Małgorzata Witkowska, tirelessly distribute copies of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen. They call on the spectators to create a living chain of freedom, until in the finale, they bring to the audience dozens of previously created banners with slogans derived from the Black Protest. And when the banners occupy almost all empty space, Théroigne de Méricourt, or rather Sonia Roszczuk herself, says: “Do you believe that theatre really can start a revolution? Do you believe that what we do, really opens somebody’s eyes? Do you believe that the voice that for an hour or so is trying to reach you will be remembered? Will you take something from me and live it? I am suffocating from your self-contentment and from your sense of mission.” She picks up the first of the banners and goes out with it in front of the theatre, onto the street. And waits for the audience to join her.

Stateswomen. Photo: Monika Stolarska.

But the use of banners with slogans taken from the streets, and the demonstrative exit onto the street in the spectacle Stateswomen, can be interpreted as something more than a simple recollection on the women’s Black Protest. Janiczak and Rubin use quotes and figures from the French Revolution, and contrast them with quotes from Polish politicians and public figures from recent months, showing that the French ideals of liberté, égalité, and fraternité (without sisterhood) still remain only slogans after 200 years.

The most interesting question, however, is that of the role of the theatre and the effectiveness of the activities it undertakes. Does theatre really have the power to change reality? Can the spectators coming out with banners before the theatre make any change? Or rather, are small steps more important than great gestures? How do small changes matter? How can theatre reveal the mechanisms shaping reality? In All about My Mother, the creators sought the limits of intimacy, the limits of acting, and the role of privacy in the theatre. Robert Robur showed the blurring of boundaries between the real and and the virtual, revealing mechanisms of the manipulation of people by the media. Triumph of the Will tried to determine whether it is possible to build a community in the theatre. Stateswomen, Sluts of Revolution, or the Learned Ladies asked whether and how theatre can push people to action.

Marianna Lis is a PhD candidate in theatre studies at the Institute of Arts of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. She received her MA in theatre studies from the Aleksander Zelwerowicz National Academy of Dramatic Arts in Warsaw in 2011. In the academic year 2010–2011 she studied at the puppetry department in the Indonesian Institute of the Arts in Surakarta with a Darmasiswa scholarship from the Indonesian government. She is currently completing a dissertation on contemporary wayang.

European Stages, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 by Beate Hein Bennett

- 2018 Berliner Theatertreffen by Steve Earnest

- Speaking Out by Joanna Ostrowska & Juliusz Tyszka

- Political Theatre Season 2016-2017 in Poland by Marianna Lis

- Hymn to Love in a Love-less World: Chorus of Women, Berlin 2017 by Krystyna Lipińska Illakowicz

- Wyspiański: From Wagner, Through Brecht, to Artaud? The Curse and The Wedding in Poland Today by Lauren Dubowski

- A Theatrical and Real Encounter with Zabel Yesayan: A Play by BGST by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson

- Motus and Me: In Appreciation of the Italian Theatre Group Motus by Tom Walker

- Actors without Directors: Setkání/Encounter Festival of Theatre Schools in Brno, Czech Republic, 17-21 April 2018 by Matti Linnavuori

- Ghosts, Demons and Journeys: Barcelona Theatre 2018 by Maria M. Delgado

- Two Samples of Documentary Theatre in Hungary by Gabriella Schuller

- Two East European Festivals by Steve Wilmer

- The Misted Stage: Eirik Stubø’s Stagings of Tragedy by Eylem Ejder

- Amadeus in London by Marvin Carlson

- Two Significant Losses

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016