In an interview for the Teatro Real, Calixto Bieito talked of Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s 1965 opera Die Soldaten, an adaptation of Jakob Lenz’s 1776 play, as a work that ‘reflects the infinite brutality of the twentieth century. It reflects the brutality of the Second World War, it reflects what was the Cold War, the terrors of the Atomic bomb… it helps us to see the horrors that this country [Spain] has lived through in the twentieth century… It is the scream of the twentieth century’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YxNwO4QkORI).

Bieito certainly presents Die Soldaten as an immersive experience. He wanted something of the surround sound of an installation or museum exhibit; something that the audience could not escape. To achieve this, he creates the sense that the Real has been taken over by the military. Ushers and orchestra are all in military fatigues. The cast march forward to salute the audience. Pablo Heras-Casado conducts in uniform from the stage where the huge orchestra (of 120 plus musicians) is positioned up above the singers on two levels. His assistant Vladimir Junyent, sat at the front of the stalls, is also in combat attire, conducting the singers. A giant yellow metallic scaffolding structure, designed by Rebecca Ringst, reaches up into the heavens. The orchestra sit on the top two tiers. Beneath, on the ground floor, a configuration of cage-like containers that move backwards and forwards; ladders and a hydraulic platform allow the characters to scurry across the different levels. Ringst’s design – recalling the interwoven metallic tubing of Alfons Flores industrial set for Bieito’s Wozzeck (2015) – is a yellow inferno that traps the characters unable to escape the culture of surveillance promoted by this aggressive, masculine ideology.

Zimmermann’s opera enacts its cruelties primarily on the bodies of the women who the soldiers see as their playthings. The image of Marie as a young child (projected on to the four giant screens on the stage) is juxtaposed with wild animals, rotting creatures and close-ups of the adult Marie as she suffers indignity after indignity. Suzanne Elmark’s Marie Wesener is all pigtails and smiles when the audience first see her. She skips with joy, she giggles with excitement. She wants to fall in love and have fun. Unlike her sister, Charlotte (Julia Riley), dressed in a more sombre powder blue suit, she craves adventure. Her naivety allows for easy exploitation. Rack and ruin follow when she dispenses with reliable fiancé Stolzius (Leigh Melrose) for wayward officer Desportes (Martin Koch), who degrades her for his amusement. In a class ridden society, the lower-middle-class Marie, the daughter of a mere merchant, is made to know her place.

This coming of age tale is one marked by humiliation. Desportes visits her father’s shop with the explicit intention of seducing Marie. It is a game for him. Wesener, on the other hand, sees social advantages to his daughter’s association with a nobleman and officer. Desportes’ assurance and poise is contrasted with the posture of the geeky Stolzius. The Marie of Act 1 is an infantilized young woman but her outstretched arms at the end of the act – denoting crucifixion – point to the fate that awaits her at the hands of Desportes. By the end of Act 4, she is a beggar, prostituting herself outside Lille’s city walls, bloodied and unkempt. Not even her father recognizes her.

Zimmermann paints a society where the male soldiers come together to plot Marie’s downfall. Partying is accompanied by the firing of bullets, rowdy dancing and the flashing of torches on the face of any intruder –a recurring motif in Bieito’s work. Stolzius is assaulted for daring to enter a space from which he has been excluded. Desportes rides Marie as if she were a horse. Captain Mary (Wolfgang Newerla) with whom she later has an affair when Desportes throws her aside, binds her to him with his tie. Mary has no qualms about abusing Charlotte while forcing Marie to perform fellatio. Cameras allow the action to be projected up close, invading privacy and demonstrating a culture of surveillance in action. Marie’s tears are all too evident after her furtive encounter with Desportes. Moments of intimacy (Marie putting on her lipstick) are projected for the audience’s consumption. This is a world where Marie is filmed surreptitiously, a world where nothing is private.

There is a frenzied quality to the stage action. The Countess Roche (Noëmi Nadelmann) is a jittery presence, swaying as if constantly drunk. Obsessed with her son (Antonio Lozano), she kicks Marie to the floor, making clear that a relationship between them is not possible. Her incestuous contact with the young Count evidences a closed class structure that is not up for negotiation. The Countess strips Marie and rubs the make-up abrasively from her face, she pulls her hair and removes her wig, leaving her practically naked on the floor. In Act 4 Maria is further abused by the soldiers – sat on, slapped, used as a piece of furniture. She is stained in red paint, a woman who is forced to ‘wear’ her degradation. Raped by Desportes’ gamekeeper in full view of the military, she screams out in horror. Her sister is also stripped, her tongue cut out so she cannot speak out of these abuses. A prostitute, Madame Roux (Beate Vollack) – both complicit in and a further victim of the men’s culture of violence – tears down the décor, attempting to pull apart the fabric of a system that allows such abuses. This is a world where women cannot make a mistake or change their minds. Judgement is absolute and conclusive.

Zimmermann’s score is harsh and abrasive – and the heavy percussive sounds scream out like weapons. The bows of the violinists jut out severely; the brass screeches, the percussion booms. It’s a sound that deafens and drowns to powerful effect. The audience is beaten both sonically and visually. We are witnesses to the abuses perpetrated on Marie and Charlotte. We sit and watch; we do not act; we do not intervene. Like the priest who observes from on high but does not interrupt or intercede when soldiers are beaten or tortured or women assaulted (a comment perhaps on the role of organized religion in the major conflicts of the twentieth century), we keep away. Shining spotlights on the audience puts us all under the scalpel. The production opened against the backdrop of the manada (wolf pack) case – five men from a group known as ‘wolf pack’ who repeatedly raped an eighteen-year old woman in 2015, boasting about and sharing images among themselves. They received sentences in April of this year – found guilty of sexual abuse but not rape– a move that generated widescale protests in Spain. One of the five men was a soldier and second a member of Spain’s rural police force, the Civil Guard. The timely quality of Bieito’s production could not be more evident. Zimmermann portrait of how institutions allow for the endorsement of criminality acquired a new relevance for twenty-first century Spain. Predatory gang culture is all too present and all too visible in the world that Die Soldaten references and comments on. It’s a shame that the Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico’s recent production of Tirso de Molina’s El burlador de Sevilla/The Trickster of Seville, directed by Josep Maria Mestres and playing in Madrid at the same time as Die Soldaten, was not able to recognize the context in which the work was being staged and received. The stolid, anachronistic production elicited nervous giggles from the audience during the rape scene – a problematic response at any time but particularly irresponsible at a time when cases like that of the wolf pack point to an institutional normalization of offensive, abusive behaviours.

The need to examine difficult pasts is also a feature of Azaña, una pasion española (Azaña, A Spanish Passion), directed and performed by José Luis Gómez. First seen at Madrid’s Centro Dramático Nacional in 1988, during the heady years of the new democracy, it is now restaged at the Teatro de la Abadía as part of a three-work season – the other pieces are Unamuno, venceréis pero no convenceréis (Unamunuo, you will win but you won’t convince) and an adaptation of Luis Martín Santos’s post-Civil War novel Tiempo de silencio (Time of Silence) — dealing with the importance of memory in relation to contemporary Spain. Azaña is a homage to a politician but also a model for verbatim theatre that recognizes the ways in which past and present intersect as writings from a particular moment in history are re-read by a contemporary audience.

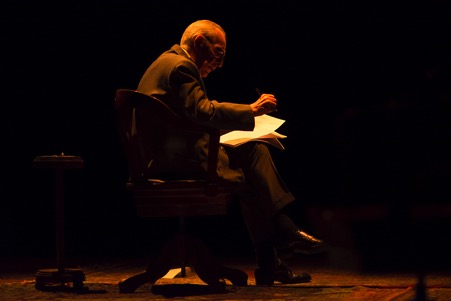

José Luis Gómez in Azaña at the Teatro de la Abadía: a contemplation of political responsibility and agency based on the writings of one of Spain’s most important twentieth-century politicians. Photo: Álvaro Serrano Sierra, courtesy of Teatro de la Abadía.

Manuel Azaña was one of twentieth-century Spain’s most important politicians. Trained as a lawyer, he also practiced as a journalist and writer. A fierce anti-monarchist and anti-clericalist, he opposed the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, endorsed by the acquiescent King Alfonso XIII. Co-founder of the Republican Action party in 1926, Azaña served as Prime Minister of Spain’s Second Republic twice – in 1931-33 and then in 1936. He promoted legislation to curb the influence of the Church, to expand secular schools, to reduce the influence of the army, and to allow votes for women. He played a key role in the formation of the Popular Front coalition of Left-wing parties in 1935, bemoaning the divisions within the Left that were to prove so corrosive to the Republican cause during the Civil War. As President of the Republic between 1936 and 1939, he witnessed the infighting that fractured the Republican war effort. Azaña resigned as President of the Republic on 27 February 1939 and died in France, in exile on 4 November 1940.

The first words that sound in Azaña are the resignation letter sent by the Spanish President to Diego Martínez Barrio, the then President of the Spanish Cortes (legislative body). Azaña recognizes the War is lost, he calls for ‘humanitarian conditions’ to avoid further sacrifice, and acknowledges his own failings. France and Britain have now recognized Franco’s government. Accused of ‘desertion’ by colleagues who remained in Spain – Azaña had already been in France for a month when he authored the letter – he faces both ostracism and exile. When the piece commences, Gómez’s Azaña is dressed in a three-piece suit. He cuts a lonely figure in a darkened, empty room with four swivel desk chairs and a number of worn rugs creating the sense of a makeshift carpet. Three ashtrays are close by. A suitcase with a hat and coat stand at the back of the stage. Sheets of paper are strewn across the floor. A woman places a lit cigarette into each of the ashtrays. Smoke lights up a piece of paper. The stage is full of shadows, pockets of light, and the endless smoke through which the spectator makes out the spectral, still figure of Azaña. The lean, angular Gómez bears no physical resemblance to the portly-faced politician preserved for posterity in black and white photographs. But this is an interpretation, an act of construction where a persona has been created in sixteen episodes from the letters, interviews and speeches assembled by José María Marco.

Sporting round, metallic rimmed glasses, Gómez creates a persona where political action is rooted in considered liberal thought and the need for reconciliation. He eschews a model of leadership based on hatred which requires the extermination of the enemy. His measured words are a far cry from the polarized rhetoric of Spain’s current generation of politicians. Azaña is not idealized but rather recognized for writings that sparkle and delight in their corrosive wit and frank analysis, for speeches that incite and enrage, for a social vision that recognizes the need for greater equality and for a willingness to recognize faults, address them and try to work towards political and cultural change.

The opening has Azaña sitting down and faces the back wall. It is as he cannot face reading this letter of resignation, which has generated so many discarded drafts, to the audience directly. A second letter to a friend in Buenos Aires explains the ‘terrible’ departure from Spain. It is as if Gómez is writing into the air, hoping that the words will be carried along to new audiences. He speaks of women giving birth on the road to France, of children perishing of cold or trodden underfoot, of ‘a crazed crowd’, of a human chain of 78,000 people on the move. ‘The generations living today will never know the truth’. Azaña thus becomes a way of inscribing this other history, a way of ‘founding something new’ that can attempt to learn from the errors of the past.

Sheets of paper litter the stage. Some sheets are discarded some are shared with the audience. Gómez’s Azaña stands and walks firmly forward, his voice echoes as if addressing a crowd in a large, open air space as he speaks of the challenge ahead, the vocation he holds. He spins the chair and moves back from 1934 to 1933, confronting Prime Minister Alejandro Lerroux in the Cortes. Azaña is a political performer, an orator of great skill who confronts his opponents with sarcasm and acerbity. He is brutally self-aware ‘an arrogant man isn’t bothered by anyone’ he informs Lerroux. He follows this up with a series of fragments from his writings where he singles out his sour temperament and cold demeanour. The audience, however, see many different Azañas. In an interview with an absent interlocutor, he sits back in a chair at times relaxed, at times leaning forward. This many answers testify to a personality that values culture – Azaña wrote the play The Crown which was premiered by Margarita Xirgu in 1931 – that recognizes the need for a statute for Catalonia, that seeks to clarify his anti-clericalism, that acknowledges the factional infighting that weakened the Republican coalition. At one moment Gómez steps briefly out of character to instant that he is simply ‘lending his voice to Mr. Manuel Azaña, serving as a base for his words’.

Azaña’s words resonate. They spin around the auditorium as Gómez spins repeatedly in his chair. Ideas and ideals recur: the need for democratic guarantees, for a Republic that prioritizes civility, for responsibility in government, for recognizing that failure is part of political life. ‘Fratricidal fury’ is lamented. At one point Gómez listens to a tape of Azaña speaking about collective effort. Those words echo out into our present. And it is into this present that Gómez steps when he moves to the front of the stage to tell the audience he has given form to Azaña’s words. These are the words of an “other”, bequeathed a stage life through Gómez. A voiceover reads out Azaña’s key accomplishments as Gómez picks up the suitcase and moves to exit the stage.

I saw the production in March 2018 as a number of prominent People’s Party politicians and businessmen were awaiting sentencing for their role in a corruption scandal that has exposed the wide-scale cronyism underpinning Spanish politics. Azaña’s words on civic responsibility appeared particularly relevant to the current situation in Spain. His articulation of the need to understand Catalonia’s position and the need to find alternatives to armed conflict reverberates in a political context where the People’s Party’s intransience created a constitutional crisis.

At a time when Spain is still struggling to come to terms with the enduring legacy of sociological Francoism. Gómez has spoken of the importance of Azaña’s ‘profound sense of honesty’ as an example for contemporary Spain. Azaña presents Spain not as a fixed entity but as an idea as well as a construct, one formed from different cultures and traditions, where melancholy and elation coexist and where education and culture provide a model for a just Republicanism where rights are recognized and respected. Azaña articulates the importance of rational dialogue rather than unguarded emotion. He never wanted to lead a Civil War, he wanted to avoid it; it’s a lesson to be headed by Spain’s current generation of political leaders.

How to present the past is the central topic of Pablo Remón’s entertaining new play El tratamiento (The Treatment) presented with a stellar cast at El Pavón Teatro Kamikaze. This is a smart, sharp look at what it means to pitch and sell something that you’re trying to develop and the poetics of illusion (as well as the delicate boundary between illusion and deceit) built into the very process of every film treatment. Interestingly, a number of the cast are known for their work in film Francesco Carril (Jonás Trueba’s alterego in a trio of films made between 2013 and 2016 – The Wishful Thinkers, The Romantic Exiles and The Reconquest) is Martín, a man who always thinks reality is rosier on the other side. Fortysomething and divorced, he is having a mid-life crisis even if he won’t entirely admit it to himself. A frustrated filmmaker, he ekes out gives screenwriting classes while writing ads for a TV sales company. But he has a project that he’s been living with for a long time, a film on the Spanish Civil War. Only at a time where the market on Spanish Civil War films appears pretty saturated, can Martín provide something different that’s likely to catch the attention of a producer? The treatment he provides will be key here.

Charlie (Francisco Reyes) pitches a treatment to an assortment of interested parties in Pablo Remón’s excellent new play El Tratamiento (The Treatment) at El Pavón Teatro Kamikaze. Photo Vanessa Rábade, courtesy of El Pavón Teatro Kamikaze.

Remón is a screenwriter who turned to theatre and his knowledge of the industry, its fickles and foibles runs through the text. The metatheatrical gameplay also evokes the smart, compact Argentine wordplay dramas of Rafael Spregelburd, Mariano Pensotti and Claudio Tolcachir – which Remón has acknowledged as influences on his writing. The action evolves on Monica Boromello’s simple but effective set – a horizontal frame like that of a cinema screen – where props hang on the back wall, picked off as necessary. A doll becomes a baby, jackets and hats allow for quick changes of character, a guitar provides a musical interlude. Microphones are passed from one character to another allowing the actors to step in and out of role so the action can be contextualized swiftly and urgently. By the end of the production the wall is empty. Martín’s tutoring of his student Charlie (Francisco Reyes) is often very amusing as Charlie’s body of references occupies a narrow cinematic terrain of zombies and bombings. It’s all about instant effects and candy for the eyes, about the problems that result when one commercial model of making work dominates. Martín’s screenplay is reshaped by the trio of ‘successful’ film professionals who each want their slice of the drama. Martín will do whatever is needed to get the film made and eventually the script bears little resemblance to the family episode that inspired Martín. It’s the extra-terrestrials making an appearance to get in Franco’s way that steal the day.

Martín has much in common with Woody Allen and Nanni Moretti’s angst screenwriters. He’s a man who can’t help looking back wistfully to what might have been and his dwelling on the tender relationship with Chloe, his first love (played by Aida Garrido) gives the film a whimsical quality that never appears sentimental or overplayed. The title – a play on the dual meanings of treatment – also indicates how words can hold meanings that testify to the slippery, unstable nature of language.

The Treatment is a piece about the fictions we create as we make our way through life. Fiction is a way of facing the awkward or the insecure. It is what humanity does to convince, to persuade, to animate, to cajoule, to inspire. Narratives are also about the ways in which we organize our memories. The piece also looks at how integrity is jettisoned when ambition is forced into limited models of success and how it is qualified. Martín finds all his principles called into question when he meets the self-centred director Alex Casamor (Francisco Reyes). Aida Garrido’s ambitious producer Adriana Vergara is a coldly calculating figure for whom care and concern mean nothing. Indeed, the image of the industry that the film conjures is hardly flattering.

Apart from Francesco Carril’s Martín, the remainder of the cast take on a number of roles, moving effortlessly and playfully between characters. The five actors have worked with Remón in rehearsal to refine and shape the text – Remón admits the finished product is very different from the script that he took into the first day of rehearsals. The result is a slick, energetic piece that powers ahead with the momentum that Martín’s worthy screenplay lacks.

I had hoped to see Barbara Lennie (quite simply one of the best actresses of her generation as her performance in Jaime Rosales’s 2018 film, a veritable Greek tragedy, Petra, evidences) but Aura Garrido took over from her from 3 July for the latter half of the Madrid run. Garrido is a wispier stage presence than Lennie, whose earthy beauty recalls Anna Magnani. It may have been Garrido’s first performance but the interplay with her fellow actors was such that it was as if she had always been part of the production and she was particularly good in the role of Martín’s first love Cloe. Remón’s play deserves to be seen in in English – it’s witty, smart, polished and highly entertaining.

Remón has often been associated with Alfredo Sanzol, another writer-director whose satirical pieces have similarly involved spirited role play from a dexterous cast. La ternura (Tenderness) returns to Teatro de la Abadia for a second run, playing out to sell out audiences, following its initial run at the theatre and a tour across Spain that has seen terrific reviews, enthusiastic audiences – 32,000 and still counting – and the Valle-Inclán Theatre Prize awarded to Sanzol. The production is a wonderful pastiche of Shakespeare’s comedies – the titles of fourteen of them are dropped skillfully into the piece in a knowing game with the audience. The plot is briskly paced, the acting is knowing, the writing (blank verse) crisp and entertaining.

Adversaries and lovers tumble in a farcical frenzy of desire in Alfredo Sanzol’s La Ternura (Tenderness) at Teatro de la Abadía. Photo: Luis Castilla, courtesy of Teatro de la Abadía.

An empty stage with a simple blue curtain at the back and two stumpy tree trunks stage right. The year is 1588 and two princesses, Salmón (Natalia Hernández) and Rubí (Eva Tranchón), are on a galleon as part of the Armada, sailing from Spain to England in the company of their mother, the Queen Esmeralda (Elena González). They are to be wedded in arranged marriages with the Dukes of Essex and Lancaster once victory over the English has been secured. Only Esmeralda has a cunning plan, conjuring a tempest (in veritable Prospero manner) to sink the ship they are travelling on in the hope of creating a new feminist republic on a deserted island where she and her daughters can be free of the influence of meddling men. Only, unbeknown to Esmeralda, on that same small island, there is a father Marrón (Juan Antonio Lumbreras) who has lived there for twenty years as a woodcutter with his two sons Azulcielo (Javier Lara) and Verdemar (Paco Déniz) in order to escape what Marrón sees as the malign influence of the opposite sex.

When Esmeralda realizes that the island has prior inhabitants who have a misogynistic attitude to women, she hatches on a plan for the trio of noblewomen to disguise themselves as shipwrecked soldiers in order not to arouse suspicion. The fun and games begin as disguise begets role play, misunderstandings, vaudeville routines and the falling in and out of love with the aid of herbal potions. Marrón is no simple woodcutter but a magical doctor able to fashion remedies from the island’s plants and herbs. The misuse of Marrón’s love potion leads to one of the funniest sequences in the play: the disruption of the configuration of lovers that sends the three couples into a frenzy of desire where anyone and everyone falls for the other, creating a tower of bodies on the floor as mother, daughters, father and sons all tumble together in an inebriated mass of feverish passion. Only with a giant wave of smoke from the island’s volcano are things able to return to a semblance of what they once were.

This is a feisty play with a timely message. The trio of women are anything but passive beings. Enterprising, resourceful and imaginative, they create a range of excuses to keep the men at a distance. In veritable screwball comedy manner, the piece becomes a battle of the wits between Juan Antonio Lumbreras’s Marrón (with his wonderfully elastic face and expressive hands) and Elena González’s forceful Esmeralda who has a plan for everything (or so she thinks). And as Rubí and Verdemar and Salmón and Azulcielo fall into lust (or possibly love), there’s a further battle as the resourceful daughters try to ensure that their mother doesn’t find out what’s going on.

The production is gloriously entertaining. Esmeralda gives a long list of the exquisite food that has been left on the ship – a virtuoso recital of mouthwatering dishes – as the three women bemoan their hunger. There’s a keen sense of irony, delicious situations involving confessionals – in one case Rubí confesses to her mother who has been temporarily transformed into woodcutter that she is in love with Valdemar – and a keen pacing with the energy of the constant wave of comings and goings coming from farce. Fernando Velázquez’s music has a sense of energy and momentum that would not be out of place in a Hollywood action picture, propelling the action purposefully along. The characters’ bursting into song at opportune moments brings further pleasure. The three women singing of the merits of desert islands for spirited women as they wave goodbye to the Armada is highly enjoyable but there’s an equally amusing number about the merits of drinking from the three men just before the women come in to interrupt their protected paradise.

Sanzol directs with a keen sense of economy. The tempest is conjured by a yellow sheet with the simplest of moves by the two princesses. Alejandro Andújar’s costumes create patterns of colour on the stage – the lush green of Esmeralda’s dress, and dark red of Rubí and rust of Salmón’s matching outfits contrast with the simpler cuts of the men’s attire. Marrón is dressed as his name signals, in a plain brown tunic, with his two sons who tower over him in similarly cut outfits in complementary shades of muted blue (Javier Lara’s Azulcielo) and green (Paco Déniz’s Verdemar). The beards the women wear in their disguises as soldiers are suitably ludicrous and they clank and clutter amusingly in the ill-fitting armour. Juan Antonio Lumbreras’s Marrón waves his hands as if they were windmills. Paco Déniz takes giant steps as if wanting to make a statement wherever he goes, stepping out from his father’s shadow. The three men create the sound effects of wildlife on the island – hens, lambs, bats. Eva Trancón as the taller Rubí uses her height well, her goofy smile a contrast to her sister Salmón’s blank demeanour. Natalia Hernández has something of the silent comic’s ability to pull a face from the most insipid of expressions. Javier Lara as the naïve Azulcielo (the name means skyblue) is like an infatuated puppy who is confused by his attraction to the sergeant – Salmón in disguise, gleefully playing a man playing a woman to help him through his confusion.

Indeed, play is the order of the game. When Juan Antonio Lumbreras tells the audience he is interpreting an old man, we believe him. Actors are here not locked into roles determined by age or physique. Tenderness celebrates the power of the stage as a place of transformation, a space where anything is possible. This is a play about what it means to love and to be loved, where, as an audience, we are urged to (re-)consider our prejudices. At the end the younger couples go to forge a new future for themselves and Esmeralda and Marrón are left alone to forge their relationship. They have had to let go of their children and allow them to find their own way in the world. They can’t control everything. Tenderness is about encountering challenges and situations that we are not prepared for. It’s about confronting difference with respect and learning that respect is a fundamental part of loving. Returning to the Early Modern times, Sanzol crafts a tale about contemporary Spain and its need to take risks respectfully without looking back simplistically to a nostalgic past – celebrated in books like María Elviar Roca Barea’s 2016 Imperiofobia y leyenda negra (Empire-phobia and the black legend) – that stops it preparing for the demands of the present. As one character remarks at the end, ‘desert islands don’t exist where freed of ourselves we can return to the illusion of paradise’.

Henrik Ibsen’s Enemy of the People is given a timely new outing by Álex Rigola at the Pavón Teatro Kamikaze – the opening production of the 2018-19 season — with the title Enemigo del pueblo (Ágora). (The bracketed addition gives a clear indication of where Rigola is planning to take the play.) The audience enters to six giant white balloons spinning on a horizontal wooden bar held by actress Irene Escolar. Each balloon spells out a letter E-T-H-I-K-E. She juggles the bar carefully as if not wanting to lose her balance. Nao Albet strums a guitar, Óscar de la Fuente taps a brush on a table making a gentle percussive sound. Francisco Reyes takes over the control of the balloons. Behind them a giant black board with a cartoon drawing of a spa on a hillside. Israel Elejalde introduces the evening’s ‘entertainment’. For those of us expecting a contemporary rendition of Ibsen’s classic play pitting individual conscience against institutional corruption — and the contemporary costumes of the actors could lead to that assumption — Elejalde and Escolar lead us in a different direction. The context appears to be a theatre company preparing a production of Enemy of the People who use it as the springboard about a series of questions about their own relationship to the system on which they depend for funding. Our programmes each hold a green Yes and red No sheet that we are told by the cast to flash above our heads to vote on key questions they will put to us. The audience are here to ‘test the system’ we are told by de la Fuente. The questions are big and abrasive. Question One: do we believe in democracy? The votes are swiftly counted by the actors skilfully making their way through aisles. 203 say yes, 55 no. The question and the numbers involved are written on the blackboard by Reyes.

Irene Escolar and Israel Elejalde in Àlex Rigola’s Enemigo del pueblo (Ágora) Enemy of the People (Agora) at the Pavón Teatro Kamikaze. Photo, Vanessa Rábade, courtesy of the Pavón Teatro Kamikaze.

The pacing is, initially, brisk and urgent. The second question follows in quick succession: Should the Pavon-Kamikaze team say to the administrations that fund them what they think without fearing any consequences will come from their actions? Again, it’s a blunt yes or no answer that we are offered. 236 say yes; 21 say no. Again, the numbers are scribbled on the blackboard.

Then comes a third question. We are told it’s the ‘game of democracy’. Do we want the action to go ahead? We are asked to vote on a particular question that is loaded. If we say yes, we suspect that the action will be halted and Enemy of the People not be performed. The initial question is superseded by the realisation that a no vote means the staging of the play will happen. 85 say yes; 162 say no. The no vote means the play goes ahead. (I heard that on the night of the dress rehearsal the ‘yes’ vote prevailed and nobody got to see the truncated version of Enemy of the People that follows).

And truncated it certainly is. The action is largely narrated by the actors who use their given names rather than the names Ibsen deploys. Nao and Oscar run the Public Enemy magazine, a veritable source of countercultural culture in the town that they are terribly pleased – the word smug comes to mind – about. Israel is the doctor who contributes to the local magazine. He is concerned about the visitors who seem to have suffered gastric problems during their time at the spa; he then commissions the report to see why this is. The results show that the water that services the spa is contaminated. Nao has another answer: ‘It’s the contamination of society, not the water’. Francisco works in computers and he also represents the businessmen of the town. He is no disinterested party. Irene is both Israel’s sister and the mayor who also holds keen business interests in the spa. She wants to continue to attract visitors –especially as neighbouring towns now offer competitive spa experiences. The option presented by Israel shows that two years of works should see the problem sorted but nobody has the patience to wait that long. This is a society in a hurry to keep hold of their (ill-gotten) gains.

There is an attempt to link this to contemporary society. The actors speak of a town ‘sunk’ by the economic crisis – a reference to the economic slump that has beset Spain since 2007. Israel champions the importance of ‘disinfecting’ society – a comment on the wave of corruption scandals that saw Mariano Rajoy ousted as Spain’s Prime Minster in June 2018. Nao and Oscar are keen on the principle of principles. ‘I won’t sell myself’ Nao says haughtily. Oscar convinces himself of the importance of changing things from the inside. Irene walks around the vacillating men who are all so keen on high handed gestures of high moral standards until the reality that they will lose advertising – and thus revenue – kicks in. Nao and Oscar’s swaggering gets less confident, less assured. Nao opts to pull Israel’s article on the affliction besetting the spa.

The piece is very much addressed to the audience. There is no fourth wall here. We are confronted and implicated and asked to contribute with questions on what should happen next. Bárbara Lennie – one of Spain’s most acclaimed actresses who was seen at the Pavón Kamikaze earlier in the year in Pablo Remón’s The Treatment – is outed by one of the onstage actors. She is ‘invited’ (some might say coerced) on stage to chair the debate. Her early reticence suggested this was a spontaneous act and she didn’t look entirely comfortable but gradually relaxed into the role. Questions followed, reflecting on the points made by the different characters. Israel challenges that ‘the majority knows nothing’. Nao retorts that ‘the majority is the essence of the people’. Israel spouts Jason Brennan’s views in his 2016 book Against Democracy that politics has been converted into a game of football dominated by hooligans who look at it as a recreational activity and follow it with the intensity of obsessive sports fans. Instead, he posits an alternative – epistocracy – where it is the knowledgeable who vote. Audience members are quick to provide reflections on competency to vote, the dangers of sentimentality and emotion in a society where reasoning has been replaced by feeling, and the importance of citizenship as a commitment. Voting is a right but should it be a responsibility? The discussion feels earnest rather than urgent. ‘Who determines who is fit to vote?’ somebody asks from the audience. But it’s a question that’s lost in a structure that allows the soapbox to prevail. The audience are asked to vote on whether we believe in universal suffrage. Another black and white question; another option reduced to a yes or no answer. The discussion is itself turning into a game of football. Opinions kicked out in a way that give anyone who wants it their five minutes of fame.

I am starting to feel distinctly uneasy. The actors are focused and impassioned. The performances are crisp but I am disturbed by the black and white nature of the questions they are throwing at the audience. We are only given the option of answering yes and no, as if this were a referendum. (I abstained on two occasions but abstentions were not acknowledged, irregularities in the count ignored.) Referendums, as the situation in Catalonia and post-Britain demonstrates, are not particularly nuanced. Democracy should be. Rather than move between black and white, perhaps the piece could have explored the grey area in which the tough decisions of democracy should be made. Nobody asks why do people vote? How can legislative bodies help voters to care? The word ethics is, if I recall, never mentioned in the production. In a society where democracy could be equated with voting on talent shows like Operación Triunfo and Got Talent España to see who is thrown off each week, how does society ensure responsibility and understanding are built into the process of voting. Do we really know what we are voting for? What does democracy mean in a country where a significant proportion of the population lived through a dictatorship. The final question asks the audience to answer whether they believe in universal suffrage. 168 say yes; 74 say no. If we don’t believe in it, what do we replace it with and how would it operate? The latter question is evaded. That worries me. Israel ends with a configuration of Stockmann’s Act Five words – eyes blazing, ardour infusing his uplifting words. Nao sing’s Radiohead’s ‘Creep’ –a song about wanting to matter and making an impact. The balloons are released and rise up and out of the audience’s view. The lights darken. The audience leave the theatre. Variations of the verb to love are projected on a screen above the stage. The moments all work aesthetically on their own terms but I am not entirely convinced they come together as more than their individual parts. I am left wondering what both collective and community mean for Rigola. And whether the production has actually reproduced many of the issues it supposedly critiques.

This is more ágora than Enemy of the People. The play’s arguments are presented with broad brush strokes. Should a theatre company accept funding from those it doesn’t agree with? I would rather have had a discussion about why there there is a system of funding in place which is so linked to political interests. Changes of government bring about a change in key civil service positions that locks planning into short four-year cycles of short-term planning rather than long term strategic objectives. The production seemed curiously hermetic and closed in on itself. Guillermo ‘Willy’ Toledo – originally announced as part of the cast – pulled out of the production 13 days before the opening citing ‘diary issues’ as the cause. The actor is known for his radical statements on a range of political and religious issues and at the time the production opened was facing a case from the Association of Christian Lawyers for ‘alleged humiliation of Christian interests’. I wonder why the issue didn’t make its way into the production to open it out to a broader socio-political context. Rigola’s resignation at Madrid’s Canal theatres – a response to the brutality demonstrated by police on the 1 October ‘referendum’ hovers over the action like an unspoken family secret.

I longed for the dramatic urgency of Thomas Ostermeier’s 2012’s Enemy of the People where the mood in the auditorium in the play’s fourth act seemed genuinely menacing and unsettling as Stockmann delivered a tirade to an audience that spoke out about a plethora of current concerns (at least on the night in 2014 when I saw the production at London’s Barbican Centre). Ostermeier largely unnoticed conducting the stage action from the back of the auditorium. in Max Glaenzel’s bare set is dominated by a blackboard; it recalls the blackboards Ostermeier used in his production which were scribbled and scrawled on and then wiped clean – suggesting a whitewashing of Stockman’s findings. Nao Albet’s final number also harked back to the rendition of David Bowie’s Changes offered by Christoph Gawanda’s Stockman and his pals in Ostermeier’s staging. Ostermeier crafted a staging where as Stockman observed, it isn’t the economy that is in crisis, the economy is the crisis.

I also questioned why, with public statements made by Rigola around gender parity and representation in theatre, that there was only one woman in the cast. Irene Escolar is excellent – she suggests warmth and complicity, she speaks to the audience in a casual, friendly manner that relaxes us and lures us into a position of false security. Her remarks, however, hide a more complex series of self interests that she displays in the role of a ‘civic-minded’ businesswoman who will stop at nothing to get her own way. Her brother can be dispatched to a distant place until the scandal blows over and then quietly return when the time is right. Israel Elejalde doesn’t appear quite as vain as I remember recent Stockmanns: Christoph Gawanda’s in Ostermeier’s reading and Francesc Orella’s in Gerardo Vera’s 2007 staging. Stubborn and opinionated yes, vain no. But as the discussion in the theatre with the audience demonstrated, we can all be opinionated (dare I say narcissistic) given a microphone and the space to unravel. Perhaps we are all enemies of the people. Perhaps Israel Elejalde’s Stockmann is a mirror of the audience. Self-interest besets and corrupts even those who would see them- (or indeed our-)selves as above such temptations. Love here gravitates around love of self rather than love of other, and it left me distinctly uncomfortable as I exited the theatre.

Maria M. Delgado is Professor and Director of Research at The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London, and Honorary Fellow of the Institute for Modern Language Research at the University of London. Her books include “Other” Spanish Theatres: Erasure and Inscription on the Twentieth Century Spanish Stage (Manchester University Press, 2003, updated Spanish-language edition published by Iberoamericana/Vervuert, 2017), Federico García Lorca (Routledge, 2008), and the co-edited Contemporary European Theatre Directors (Routledge, 2010), A History of Theatre in Spain (Cambridge University Press, 2012), and A Companion to Latin American Cinema (Wiley-Blackwell, 2017). She is currently Co-Investigator of an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project ‘Staging Difficult Pasts’. The research for this article is part of this project and was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council [grant number: AH/R006849/1].

European Stages, vol. 12, no. 1 (Fall 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 (Part II) by Beate Hein Bennett

- Report from Berlin (June 2018) by Marvin Carlson

- Othello, Shakespeare’s New Globe by Neil Forsyth

- Resistance Through Feminist Dramaturgy: No Way Out by Flight of the Escales by Meral Hermanci

- 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe by Anna Jennings

- The Avignon Arts Festival 2018 (July 6 – 24): Intolerance, Cruelty and Bravery by Philippa Wehle

- Le Triomphe de l’Amour : Les Bouffes-du-Nord, Paris, June 15—July 13, 2018 by Joan Templeton

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018 of Brussels (Belgium) by Manuel García Martínez

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Contemporary Nordic Performance at the 2018 Arctic Arts Festival by Andrew Friedman

- A Piece of Pain, Joy and Hope: The 2018 International Ibsen Festival by Eylem Ejder

- The 2018 Ingmar Bergman International Theater Festival by Stan Schwartz

- A Conversation With Eirik Stubø by Stan Schwartz

- The Estonian Theatre Festival, Tartu 2018: A ‘Tale of the Century’ by Dr. Mischa Twitchin

- BITEF 52, World Without Us: Fascism, Democracy and Difficult Futures by Bryce Lease

- Unfamiliar Actors, New Audiences by Pirkko Koski

- Corruption, capitalism, class, memory and the staging of difficult pasts: Barcelona theatre and the summer of 2018 by Maria Delgado

- Reframing past and present: Madrid theatre 2018 by Maria Delgado

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018