By Chris Rzonca

We all had our temperatures checked. We all filled out forms affirming we were Covid-free. We all wore masks, of course. But when we took our seats, squirming in the dark on the hard chairs, we were alone, yet at the same time together, sharing the space of live theatre again.

And this performance had theatre to spare, starting with the nearly empty stage holding only a few plain chairs, randomly placed, in which actors sat or slumped, separated from each other; little islands awaiting our arrival. A long mirrored wall cut diagonally across the entire left side, reflecting images of the actors and behind them another stage wall, or the back of it, revealing the flats and jacks holding it up. This allowed us to see the stage and behind the scenes at the same time. We were seeing the reflections, the insides, the bones of both the play and the characters.

Most actors were older—in fact, the ages and personalities of the characters were mixed up. Only Natasha and Masha seemed close to the age designated by Chekhov. Olga was played by an actress much older than the 28 of the original version. Most of the men in this performance seemed even older, although today we might consider them closer to middle-aged. This directorial choice strengthens the idea of the passing of time, nostalgia, and missed opportunities for a modern audience because, quite simply, as Perceval notes in the program, the world has become older as people live longer.

The English language supertitles kept us in touch with some of Chekhov’s words, even if the action didn’t always correspond to the text. That apparent disconnect only strengthened the sense of disorientation that the mirror wall presented us wordlessly. The script also contains fragments from Juliusz Slowacki, Agnieszka Osiecka and a Chekhov poem. According to the program, this performance is based on Three Sisters, but rather than another straight up talking heads version, this 3STRS is a reflection on Chekov’s, somehow making it fuller, yet simultaneously more unresolved, even secretive. Perceval owes something to Tadeusz Kantor in this. He does not interpret the text, but rather restates it mostly in movement, sound, and visual images, including some scenes of the Russian countryside projected on the mirrored wall.

Many of the monologues (or “philosophizing”) of the original text are either absent altogether or are danced or sung, perhaps to show the absurdity and pointlessness of such pseudo profound proclamations so common in Russian (and also) Polish culture. We see inside, but perhaps don’t really learn anything more; nothing much really happens. Not much makes sense. Perceval has said that theatre teaches us to accept “the sense of nonsense,” and we somehow do accept it.

3STRS, based on the play by Anton Chekhov, adapted and directed by Luk Perceval. Photo: Monika Storlaska.

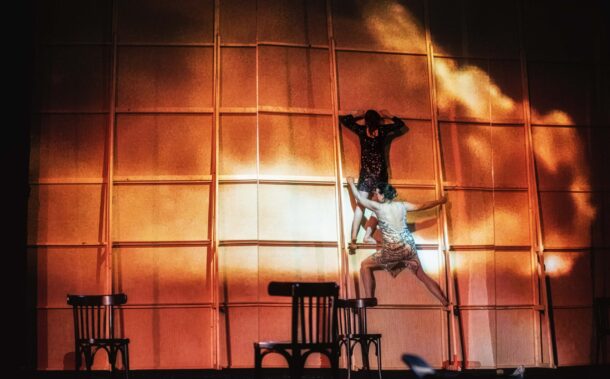

At one point we see, reflected in the long mirror, Irina and Masha quietly climb the flats (literally climbing the walls) like two slow-moving besequinned stage hands, or perhaps two prisoners attempting their escape. But of course there is no escape. They are moving, always going, but never leaving. That Godot-like reality is reinforced throughout the performance as the actors move, usually slowly, glacially, at a Wilsonian pace that only serves to further root them in place.

In a surprising reversal of some unwritten rule of theatre, instead of beautiful, young female bodies, it’s the older men who disrobe during the performance. While the lighting (mostly) obscures, we are left wondering why they stripped down and carried their clothes with them while exiting the stage. Perhaps that exposure of older male bodies on stage in the twenty-first century is reason enough, or perhaps this re-enforces the sense of helplessness and vulnerability of these men and perhaps of us all. Vershinin exemplifies this idea. He is played from a wheelchair in this production. While usually seen as an alpha male, a handsome officer (albeit with a needy wife), his offstage “weakness” is here made visible. He may do wheelies with his chair in anger and frustration, but like the sisters, he too is stuck, limited, as we all are, in this pandemic world.

There are other surprises, such as occasional blaring bass notes vibrating off the mirrored wall (and our ribcages—the sound literally entered our bodies). The already reflected images on stage thus became further blurred and distorted—like a fun-house mirror. There is some frenetic dancing and shouting that replaces many monologues. The actors writhe on the floor, alone or in a scrum, where love is expressed or rejected. But there are also long silences, in keeping with Perceval’s belief in the “spiritual path that theatre follows is toward a rejection of all concepts, questions and answers, toward the acceptance of silence” which certainly encourages contemplation of the ambiguities and indeterminacies of this play.

This is a Three Sisters filleted and displayed, turned inside out, exposing the organs, reflecting the inner workings of the play, just as the flats and the jacks reveal the bones of the stage set. We are both inside and outside, looking sometimes at the actors, sometimes at their reflection, behind the scenes, listening, but also accepting silence. Thanks to the Belgian director Luk Perceval’s mind and the Polish actors of TR Warszawa at work on this great classic text, we see and hear both more and less in the play than we thought possible. Yet we are forced to realize that there can be no final resolution, no complete, startling epiphany, only bits and pieces of insight and that is more than enough.

In the end, we were reminded once again why we keep returning to live theatre.

Chris Rzonca has written about the Polish writer Andrzej Bobkowski (Polish Review, forthcoming) and other performances and theatre-related events in Poland for European Stages. His photographs have appeared in KwartalnikArtystyczany. Currently, he teaches writing as part of the Liberal Studies curriculum at New York University.

European Stages, vol. 16, no. 1 (Fall 2021)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Alyssa Hanley, Assistant Managing Editor

Emma Loerick, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berliner Theatertreffen Fights to Survive as Live Theatre Adapts to World Conditions by Steve Earnest

- Cultural Passport for Piatra Neamț Theatre Festival 2021 by Oana Cristea Grigorescu

- We See the Bones Reflected: Luk Perceval’s 3STRS in Warsaw, 2021 by Chris Rzonca

- Festival Grec 2021 by Maria Delgado and Anton Pujol

- Report from London (November – December, 2019) by Dan Venning

- A National Theatre Reopens by Marvin Carlson

- In Memoriam: Mieczysław Janowski, 1935 – 2021 by Dominika Laster

- In Memoriam: Jerzy Limon, 1950–2021 by Kathleen Cioffi

- In Memoriam: Marion Peter Holt

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2021 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2021