One of the trickiest questions of modern Shakespeare studies, put forward by L.C. Knights and repeated by many scholars, is, ”How many children had Lady Macbeth?” As every Shakespearean knows, the scholarly answers to it had almost nothing to do with the story of the bloody woman’s motherhood. However, when asked in the theatrical context, this question creates an intrigue which allows us to take a new, unexpected look at the old Scottish play. Perhaps, it is the issue of Lady Macbeth’s children that inspired Vlad Troitskyi, one of the most prominent and daring Ukrainian avant-garde theatre directors and the founder of the “DAKH” theatre, to create his ritualized version of Macbeth (2004). Ritual is traditionally viewed as one of the main sources of drama and theatre, and the only means of communication with the natural and supernatural worlds as practised in prehistoric communities. It is designed to appeal directly to the deepest layers of consciousness, to inveterate common knowledge and the collective unconscious. As theatre historians Oscar Brockett and Franklin Hildy point out, in the course of their development, ‘myth and ritual were viewed as a tool, as a language with the help of which the human community reveals, distributes and affirms their values, hopes and social relations’ (Брокетт, Гілді, p. 17). Thus, the ritualistic nature of theatre is doubtless. Moreover, ritual and the art of performance have a lot in common – they both feature actors (those who act out the story or perform the ceremony), directors (in ritual their functions are given to certain sacred personages like priests or magi), stage space and an auditorium (Брокетт, Гілді, p.18). It is also known that ritual was the first genre determiner for theatrical performances. Сeremonies which presupposed death or torture (for example, human or animal sacrifice) are the prototypes of tragedy, while harvest festivals are the precursors to comedy.

Over the course of time stage performances and rituals gradually grew apart. However, in the beginning of the 20th century new theatrical conceptions, which united performance and ritual to directly appeal to the unconscious and create magic, gradually began to take shape. One of the chief heralds of this approach – the founder of the Theatre of Cruelty – Antonin Artaud insisted that the true aims of theatre cannot be achieved by means of common sense. He claimed that it is essential to assault the spectators’ feelings and to break through their cushioned responses. The fundamentals of the cruel theatre are described in his manifestos – “instead of continuing to rely upon texts considered definitive and sacred, it is essential to put an end to the subjugation of the theater to the text, and to recover the notion of a kind of unique language half-way between gesture and thought… In accordance with these principles we will make such a production in which all the means of direct impact could be used in their totality; the creator of such a show will not be afraid to go as far as possible in order to investigate the sensitivity of our nervous system with the help of rhythms, sounds, words, distant echoes and whisper… (Artaud)”

The doctrine introduced by Artaud has been integrated into the artistic method of Vlad Troitskyi. Being a daring experimenter, this director has mixed it with elements from ancient Greek theatre, prehistoric rituals and postmodern stage practices. All these theatrical techniques were used to produce three Shakespearean tragedies – Macbeth, King Lear and Richard III – which, from the director’s point of view, could serve as the best artistic mirrors of present day Ukraine. Thus, the trilogy Mystical Ukraine was created, which is ”the result of common multidirectional effort in revealing and discovering the hermetically sealed energy of Ukrainian land and culture”. The trilogy comprises shows defined by Troitskyi as the ‘prologues’ to the Bard’s texts. This very claim creates certain genre expectations and presupposes interpretative mechanisms – if it is possible to make post-Shakespearean representations of well-known plots, why not try and reconstruct pre-Shakespearean ones?

Theatre practitioners usually utilize different motifs when they refer to the Bard’s dramatic legacy. However, there is usually an abundance of perplexity and even negation – people keep asking why new productions of this dead white man are necessary while there are so many new, daring playwrights who raise the relevant, contemporary questions in an appropriately shocking manner. Antonin Artaud even accused Shakespeare of implementing the idea of the so-called ‘non-interested theatre’, which avoids directly assaulting the public with mind-blowing images, thus, sparing their minds and not giving them unforgettable impressions. Troitskyi’s stage experiments sort of reconcile Artaud’s radicalism and Shakespeare’s universal cultural appeal. Combining both archaic and post-modern techniques of theatrical narrative in a rather bizarre manner, the Ukrainian director manages to create a very specific artistic space where the present and the past, the global and the local, the tragedy and the sacrifice intermingle in order to hit spectators right at the centre of their sensitivity and thereby provoke catharsis in the true Aristotelian sense of the word.

Troitskyi’s Macbeth is structured by three main components – Shakespeare’s story of a treacherous thane, the traditional context of Ukraine, and ritualistic elements appealing to instincts and the collective unconscious. Indeed, little remains from the original Scottish play in Troitskyi’s production, simply because it is a perfect specimen of the so-called ‘textless’ Shakespearean play. In accordance with Artaud’s ideas of the life of definitive and sacred texts on stage, the Ukrainian director deliberately removes verbal components and transposes the well-known plot into the sphere of total action – silent and hyper-realistic. Troitskyi sort of peels off all historical, stylistic, culturological and interpretative redundancies which the play had accumulated over the course of centuries in order to gain an absolute exposure of the conflict which remains at the heart of it. Here, he employs the so-called ‘creation of a pre-text’ (in the widest meaning of the word) out of the classical text. The Bard, who never invented stories, would create certain referencing variants to well-known plots. What Vlad Troitskyi does, in contrast, is the act of representing Shakespearean narrative in its pre-historic, pre-theatrical and pre-Shakespearean form of existence.

Such representation implies certain plot transformations – it is simplified in order to clarify the essence of the story. The production includes only a few key events from the original Shakespearean text which are the return of Macbeth and Banquo from war, the prophecy of the Weird Sisters, the assassination of Duncan, the scenes with Banquo and his bride, the madness of Lady Macbeth and the final death of the bloody couple. In addition, there is also a dramatic shift in accents as introduced by the director. The main attention in the play is given not to the betrayal and the murders, but to the Macbeth couple, whose marriage is based on true love, but is infertile. So, the climax of the performance is Lady Macbeth’s madness provoked by the witches who dump her with a doll instead of a real baby.

A group scene from Prologue to Macbeth, directed by Vlad Troitskyi. Photo: The “DAKH” Theatre.

By cutting off all the peripheral conflicts and transforming the main issue of the play, Troitskyi forms his own theatrical narration, where the elements of the original plot are altered in order to fit into both the authentic Ukrainian context and the commonly shared European ritualistic experience. As a result, the number of dramatis personae is severely reduced (there are only the Weird Sisters, Macbeth, Duncan, Banquo, Lady Macbeth and one of the two murderers remaining from the original tragedy), though some new characters like the White Bird, the bride of Banquo or the Goat are added.

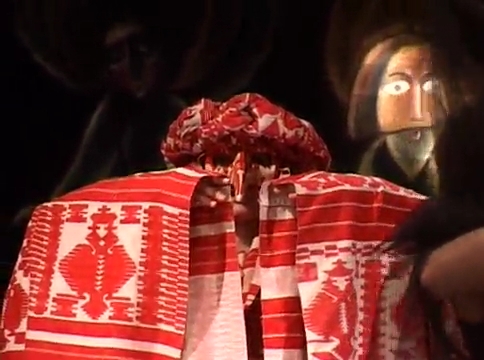

The Bird, dressed in a white costume which is tailored like a one from a Venetian carnival and covered with traditional Ukrainian embroidery in red, wears a mask of the plague doctor. The long beak of the mask provokes direct associations with the ostrich which is the traditional Ukrainian symbol of familial happiness and is believed to bring children to married couples. The Bird is a constant companion of childless Lady Macbeth who is permanently wearing a black garment and covering her white face with a black veil, as if in full mourning. The red and white Bird and the dark Lady Macbeth construe a meaningful tandem of blood, life and death which becomes the common thread running throughout the whole production.

The Bird in Prologue to Macbeth, directed by Vlad Troitskyi, 2004. Photo: The “DAKH” Theatre.

Another additional character, the Goat, is introduced in the finale to perform its, so to speak, eternal function of being a scapegoat and getting sacrificed which brings to mind such correspondent practices in ancient Greece. In modern Islamic culture, the goat is usually offered to express gratitude for the birth of a son, which, as we know, never happened in the story of Macbeth.

The Goat in Prologue to Macbeth, directed by Vlad Troitskyi, 2004. Photo: The “DAKH” Theatre.

In order to accentuate the ritualistic aspect of the performance, Troitskyi deprives his actors of their main acting instruments – words and vocal melody – which is why they have to, instead, exploit the plastic potential of their bodies. In Prologue to Macbeth, dance-like movements become the major expressive means with different origins. For instance, the Scottish warriors led by Macbeth reproduce the plasticity of Japanese samurais, the malicious Weird Sisters imitate ecstatic ritual dances, and Lady Macbeth and the White Bird demonstrate some gentle Renaissance choreography. Moreover, a lot of sense in the show is evinced by mimetic movements (giving birth to an imaginary child, riding on an imaginary horse, breastfeeding a baby doll, etc.) which emphasize the idea of the archaic ritual within the performance.

Special tribute should be paid to masks which are widely employed in Troitskyi’s Prologue to Macbeth. Their symbolism ranges from the attribute of royal power to the sign of the supernatural, the oneiric and the vile. For instance, King Duncan wears a crowned mask which after his assassination is taken off and passed to the treacherous thane. Grotesque-looking masks are worn by the disgusting creatures who accompany Lady Macbeth’s madness and the death of the couple. It is worth mentioning that in the case of Macbeth and his wife, the guises are replaced with face-covering makeup which looks quite simple yet archaic in the form of whitewash and mud. Besides that, Vlad Troitskyi widely employs national costumes and various folk crafts such as embroidery, carpet making, weaving, painting, straw work, etc. to adorn his stage design. The bright and colorful decor of the play reminds one of Sergey Parajanov’s film sets in Ukraine.

However, it’s not just actors who constitute the cast of the performance. A very significant role is given to DakhaBrakha – an ethno-chaos band which is a side project of the “DAKH” theatre actors – to provide the soundtrack. Dressed in folk costumes and exaggerated hats made from sheep fleece, and playing various drums, cellos and the drymba (the Carpathian variant of the Jewish harp), the Dakhabrakha musicians dictate the tempo and rhythm of the show. Instrumental variety enables them to produce the widest spectrum of natural sounds, whispers and rustles which, according to Artaud’s doctrine, have a direct impact on the spectators’ nervous system. Another audio impression is their drawling manner of singing that, in combination with the strong beat, can literally bring everybody into a state of trance.

Their choice of songs is also quite unusual. Troitskyi has selected a lot of traditional ritualistic songs from different Ukrainian regions – hymeneals, lullabies, vesniankas (special spring songs), Cossak tunes and harvest songs – that create the inimitable atmosphere of a folklore mystery. However, there are no mourning songs which are performed after the murders of Duncan and Banquo. Instead, some ritual spring songs are played, as if celebrating their deaths as the marker for the birth of something new.

Moreover, the presence of the band upstage, separate from the action, creates a certain parallel with the chorus of ancient Greek theatre. Indeed, they fulfill these very functions of verbally setting the scene in the prologue and commenting on the action as the show progresses before finalizing it in the epilogue. However, their comments are designed to take into account the major conventions of Ukrainian folktale narratives such as numerous repetitions, indefinite chronotopos settings, elements of the absurd, etc. The prologue cited by the coryphaeus sets the scene “in one kingdom in a distant land, once upon a time” and tells the story of a king who was a kind man but whose people were dogs. The explanatory comment comes before the climax, and briefly states the plot essence of Shakespeare’s original story, with a special emphasis on the infertility of the Macbeths and the eventual madness provoked by it.

A scene from Prologue to Macbeth, directed by Vlad Troitskyi, 2004. Photo: The “DAKH” Theatre.

The final word of the coryphaeus summarizes the entire story in general, and Macbeth’s deeds in particular. The chorus remains surprisingly neutral to the treacherous thane in spite of all the murders he is guilty of. What is more, they even suppose he could find himself in heaven for “he was a hero and he loved”. Thus, Shakespeare’s Macbeth in Troitskyi’s interpretation turns into a real Ukrainian play, as it reactualizes one of the key national stereotypes which includes finding excuse for villains, extending pardons for the heaviest of crimes, and giving clemency to the nation’s traitors. This trait of the Ukrainian national character has cost the nation too dearly over the course of its long and tragic history.

All the techniques of ritualization employed by Vlad Troitskyi lead to the total deconstruction of the Shakespeaream text. Wrapped in an embroidered Ukrainian canvas, decorated with the sounds of folk instruments and integrated into the authentic cultural practices of the land, Macbeth loses its original tragic mode of existence. Here the main source of tragic pathos is not in the deaths and murders, as in the Bard’s ”Scottish play”, but in Lady Macbeth’s infertility and madness. The assassinations of Duncan and Banquo, committed to the accompaniment of life-affirming folk songs, are interpreted as essential sacrifices which could help Lady Macbeth conceive a child. Here, the parallels with Ukrainian history and its present day state are more than obvious – there were, indeed, so many sacrifices, so many slaughters, and so many desperate attempts to fertilize the country, but it kept remaining a waste land. And for now, the task of modern Ukrainians is not to fail to turn their land from a barren Lady Macbeth to a Hermione who has found her Perdita.

Works Cited:

- Брокетт, Оскар Г. і Гілді Франклін Г. Історія театру. Львів: Літопис, 2014. Print.

- Artaud, Antonin. “Theatre of Cruelty (The first manifesto)” http://www.so-rimlee.com/literature-supernova/2010/10/21/antonin-artaud-theatre-of-cruelty-first-manifesto.html.

- Artaud, Antonin. “Theatre and cruelty”. http://ec-dejavu.ru/t/Theatre_of_cruelty.html.

Daria Moskvitina is Assistant Professor of the English Philology and Foreign Literature Department, Classic Private University (Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine), a research fellow of the Ukrainian Shakespeare Centre and a co-editor of the online project Shakescribe.UA.

European Stages, vol. 7, no. 1 (Fall 2016, Special Issue: Shakespeare in Europe, 2016)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Cory Tamler, Managing Editor

Mayurakshi Sen, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Some Quadricentennial Shakespeare in Germany by Marvin Carlson

- Tiago Rodrigues’s Antony and Cleopatra by Manuel García Martínez

- Amleto: An Opera Rediscovered by Katrin Hilbe

- Coping With the Greatest for Over One Hundred Years by Alen Biskupović

- The Art of Sharing Shakespeare: Emil Boroghină, a Romanian Sorcerer by Maria Zărnescu

- Shakespeare’s Villains and Modern Politicians in Latvia by Edīte Tišheizere

- A Queen for a King! Tom Lanoye’s Königin Lear at Schauspiel Frankfurt by Katrin Hilbe

- The Tempest: Magical Ballet Where East Meets West by Sepideh Shokri Poori

- “The Ukrainian Play”: Macbeth Ritualized by Vlad Troitskyi by Daria Moskvitina

- Les Kurbas’s Tradition in Ukrainian Shakespeare Productions by Nataliya Torkut

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016