Now in its twenty-second year, the Berlin Theatertreffen, presenting ten outstanding productions from Germany, Austria, and German-speaking Switzerland, has become one of the major European theatre festivals, but with success has come some problems. Audiences have steadily grown, and although they can still be accommodated in the touring productions given in the Haus der Berliner Festspiele, the major home of the festival, and in the larger Berlin stages when they have a production chosen, audience demand quite overwhelms smaller venues, and in recent years more intimate productions with limited seating have become an increasingly important part of the festival. I expressed my concern about this in my review last year, when only seven out of ten productions were available for the majority of festival-goers, critics included. This year only five of the ten featured productions were available, and indeed an article appeared in the Berliner Morgenpost the day the Festival opened complaining about the situation. Certainly there is little doubt, given the generally high quality and huge number of theatre productions presented annually in these countries, that ten outstanding productions created in regular theatres could easily be selected, but that doubtless many would protest such a restriction. Perhaps the Theatertreffen should consider developing something akin to the Edinburgh Fringe or the Avignon Off and still give its audiences a full festival program. In any event the current situation is a frustrating one for the vast majority of attendees, critics included, since press tickets to the small productions are few to none. In the event, like most reviewers I received tickets to five productions, literally half of the festival. Under the circumstances I feel awkward presenting a festival review based on only five of ten plays, even if these five are those to which the majority of spectators and critics were able to be admitted. Under these circumstances, I hope readers will understand if this is the last annual report we publish on the Theatertreffen.

The opening production of the Festival was Schiff der Träume, with a text based on the Fellini film And the Ship Sails On developed by director Karin Beier and her dramaturgs Stefanie Carp and Christian Tschirner at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus in Hamburg. The adaptation makes two critical changes to the Fellini original. The first is revealed at the very beginning. In Fellini, the ship’s mission is to carry the ashes of a world-famous diva to their final resting place. In Schiff, the diva has become an equally famous conductor/composer, and most of the company members of his orchestra. The production begins with a darkened stage and individual orchestra members scattered about in small spotlights, making isolated noises, some musical, some simply percussive. Eventually these are woven into a rehearsal of part of composer Wolfgang’s master-work “Human Rights No. 4” a lengthy parody of New Music, composed of apparently random bits of sound and silence, punctuated by the slapping on the floor of large swimming fins worn by the great comic actor Josef Ostendorf, seated prominently upstage.

Schiff der Träume – A European requiem after Federico Fellini, directed by Karin Beier. Photo: Matthias Horn.

Much comic capital is made not only of the music and the rivalry between orchestra members, but also of the contempt in which the departed Maestro holds each of them, spelled out in detail in a final letter from him read by his assistant, Charly Hübner, to open the evening. Another major source of farcical language and action is provided by the cruise organizers, the chief steward Jan-Peter Kampwirth and his physically and verbally challenged assistant Lina Beckmann. These deliver a whole series of garbled emergency instructions, travel brochure hyperbole, and elaborate and bizarre menu options (often made more bizarre by the frequently scatological stammerings and mispronunciations of Lina). Further farce is provided by the active involvement in the proceedings of the ashes of the departed Maestro, at first prominently displayed downstage center in a golden urn and subsequently spilled, scattered, replaced by substitute powders, drifting in the air and causing various orchestra members to sneeze and dust their coats.

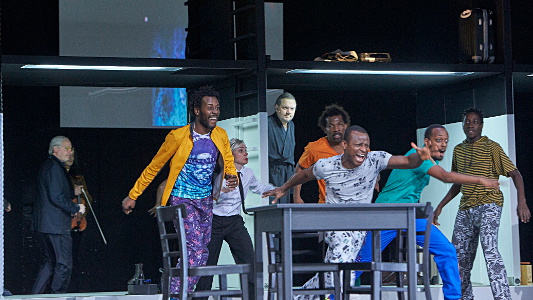

After about an hour of such activity, the action sharply changes. The rather stark structural shipboard setting of Johannes Schütz is at last fully and rather starkly illuminated, as a set of new characters appear. This is the second major adjustment to the Fellini original. In the film, set at the beginning of the First World War, the cruise ship takes on a group of Serbian refugees. In Beier’s updated version, the refugees are contemporary black non-Europeans. When these “others,” presumably to be transported quietly below-decks, suddenly invade the elite upper deck, the play takes on a completely new dimension, suddenly becoming a high relevant political statement.

Nor is this statement confined to general European political and social concerns, but also involves the contemporary German theatre itself. Traditionally tied to the white middle and upper classes, it has generally reflected in neither its performers nor its audience the rapidly changing demographics of the country and this city. One important result has been the growth of an independent theatre scene in several large German cities, among them Berlin and Hamburg (where this production was created), developed and attended by the public and performers excluded from the traditional theatre, among them emigrants from African nations like Rwanda and the Ivory Coast. The German dance scene has provided some more general exposure to these artists, but the theatre hardly any. Thus the sudden emergence of these performers from the lower deck into the stage world inhabited by film stars like Charly Hübner and by stage stars like Bettina Stucky and Josef Ostendorf resonates on a number of levels.

Schiff der Träume. Photo: Matthias Horn.

The remainder of the play, after the intermission, departs from Fellini and becomes a kind of forum among the representatives of old Europe and those who now claim a place for themselves there. The newcomers are anything but humble in their demands. They consider the old order decadent and declining, and desperately in need of their youthful vigor. They will do away with such corruptions as stage nudity and sensual indulgence and replace these with a more honest and upright theatre. The old guard, torn between a humanitarian desire to accede to these demands and a conservative desire to protect their privileges and traditions, engage in an extended debate with the newcomers filled with cultural clichés and generalizations all too familiar from contemporary discourse. At last they find a kind of common ground in the “universal” appeal of music and dance and join in a theatrical if clearly ironic festival of togetherness.

If the production were half as long (it runs three and a half hours), it would be twice as effective. The opening ninety minutes, before the “others” appear, composed entirely of cruise parodies, musical jokes, petty quarreling, and slapstick business with the funeral urn and other properties, goes on far longer than is necessary, and the same is true of the post-intermission discussion, which is also insightful and entertaining for half an hour or so, and then seems merely repetitive. The overall concept is very impressive, and one can understand why the work was selected, but surely a leading director and two experienced dramaturgs should have had a better sense of the proper duration of this presentation.

The second Theatertreffen production I attended was a distinctly postmodern version of Ibsen’s Enemy of the People from the Zurich Schauspielhaus, directed by Stefan Pucher. Although Ibsen’s general plot is followed, the physical realization of it departs very far from the original and the actual lines spoken almost as far. Dietmar Dath, the adapter, is a journalist and science fiction writer and he and director Pucher have moved Ibsen’s work into the near future and made his community into an apparent neoliberal paradise, where a healthy and happy wired-in community seems to thrive under the benevolent protection of late capitalism. Cell phones, laptops, even moving robots as minor characters, are constantly used by all. Many conversations are carried on by videophone, shared with the audience by projected images, and even those that are not are often marked by the practices of this brave new world. An early confrontation between Thomas Stockmann (Markus Scheumann) and his brother Peter (Robert Hunger-Bühler), for example, is carried out with the two of them seated facing the audience on side-by-side stationary exercise bicycles, which they pedal calmly or furiously depending on the intensity of the conversation. Fitness is indeed one of the town’s preoccupations. From time to time the music director and physical therapist, her own moves distinctly robotic, leads the citizens in a TV-style exercise training session to a pop score. Vegetarianism is a popular local choice.

The evening begins with a large projection of a Google globe on the rear wall (the stage, designed by Barbara Ehnes, is essentially a large neutral white box). The visual field zooms in closer and closer, eventually to find the location of the play, a small town near Zurich. A large-scale model of the town’s center occupies much of the upstage area during most of the evening, and assistants with hand-held cameras move around it, projecting images onto the back wall of its handsome if rather sterile public buildings, parks and spas. The source of all this prosperity is also included: a large complex of drilling towers for the extraction of oil.

Henrik Ibsen’s Enemy of the People, adapted by Dietmar Dath, directed by Stefan Pucher. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf / T+T Fotografie.

What Dr. Stockmann has discovered in this version is the now hardly revolutionary problem that the fracking utilized by this industry is poisoning the town’s water supply. As in Ibsen’s original, his discovery is denounced by his brother and at first warmly supported by Hovsted (here Mrs. Hovsted, the head blogger of the “democratic portal” DEMOnline, played by Tabea Bettin), her assistant blogger and fact-checker Billig (Nicolas Rosat), both of whom hope to use Stockmann’s discoveries for their own political advantage, and Aslaksen, here a cautious software contractor (Matthias Neukirch). As in the original, these all desert the doctor when faced with the financial consequences of his discovery.

While this sequence of events follows the original fairly closely, the conversation, especially in the first part of the play, is carried on in a language so full of highly technical and clichéd turns of phrase from global hypercapitalism, such as e-government and cross-border leasing, that it becomes almost another dialect, quite difficult to follow. There is no real shift of location for the town meeting—Dr. Stockmann simply seizes control of the stage as a curtain is lowered behind him. His opponents first try to silence him and then ask the audience to choose between him and his brother, leaving this assembly if they support the latter. They encourage members of the audience to join them out in the lobbies. I am told that in Zurich, those who left and those who stayed were about equal in number, but in Berlin only about a quarter of the audience left. In the lobby they were given refreshments and greeted by Stockmann’s opponents with mikes and video cameras, asking their opinions. Large video monitors allowed them to see Stockmann still speaking inside, while those inside saw projected above Stockmann’s head scenes from the lobby. After Stockmann had delivered his speech against democracy, he was shouted from the stage by the returned outsiders and he and his family, followed by a video camera, left the stage, went out into the lobby, through a connecting passage and back on stage for the closing sequences.

In the evening’s most spectacular effect, the large model of the town slowly ascended, mounted on a huge teardrop of earth, with blue oil drilling lines going down from the town to spread out underneath it to extract the oil. This huge mass slowly disappeared into the flies, leaving a large pit in the floor from which the Stockmann family appeared.

Despite all the technical display, or maybe in presumed accordance with it, the acting was on the whole curiously flat, especially that of the women. Petra (Sofia Elena Borsani) and Mrs. Stockmann (Isabelle Menke) were especially given to spending long periods of time looking blankly out at the audience. This seemed particularly odd in the case of Mrs. Stockmann, who early in the play is berated by the more “liberated” younger women for abandoning her university training and becoming “merely” a housewife. She responds with the classic post-feminist defense of how demanding and professional a responsibility it was to support her husband and raise a family, all of this supported by a series of life-action and TV-style home management animations on the rear wall. I found this extended sequence somewhat beside the point when it occurred but assumed it would be developed as an important part of the production, but in fact for the rest of the play Mrs. Stockmann remains the rather minor supportive character she is in Ibsen, most notably in the final scenes, where as in Ibsen, she tends to fade into the background. Perhaps some ironic point was being made about women’s role in the new society, but it was certainly not clear. The main thrust seemed not just the updating of Ibsen, but the creation of a satire on late capitalism created at the cost of most of the interpersonal complexity of the original.

Next came another Ibsen, also one which I found innovative, but not in a particularly stimulating or memorable fashion. It was John Gabriel Borkman, a creation for the 2015 Wiener Festwochen by Simon Stone of the Belvoir St Theatre in Sydney, Australia. The most striking thing about the production was its setting. The large Festspiele stage was stripped to the walls and completely covered to a depth of two or three feet by a rolling vista of artificial snow, which fell steadily throughout the intermissionless two hours of the production. This thick carpeting allowed the actors to enter by simply emerging from the snow—apparently they are able to survive under it for extended periods—and to exit simply by burrowing in. Aside from the winter image of the play, however, nothing in the concept or the action particularly justified this setting, and the actors for the most part simply floundered about in a white void, sometimes referring vaguely to going up or downstairs or outside, but never giving us any sense of the actual existence of such spaces.

Martin Wuttke, one of the greatest living German actors, was continually interesting, as he always is, playing Borkman as a scraggly-haired tramp-like figure bundled in ill-fitting overcoats. He had much more the feeling of Beckett than of Ibsen, however, especially when he spent much of the central portion of the play trying in vain to make an ancient TV set work, an action which had no clear relationship to anything else in the production, especially since much of the conversation was about the internet, Facebook, and similar technologies of a much later era than the TV. The one thing that was clear in this interpretation is that adapter Stone has taken very seriously the line in the play that Borkman’s story can be either a comedy or tragedy depending on one’s point of view, and he has apparently decided to present a kind of absurdist comedy. Only Wuttke, however, seemed to be trying to do this. Indeed he had several scenes of running through a variety of comic grimaces that recalled to me his recent performances in Molière’s The Imaginary Invalid at the Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz in Berlin. None of the other characters seemed to have any such intention, however. The usually excellent Birgit Minichmayr played Gunhild as a continuously drunken, chain-smoking frustrated wife out of a 1940s Hollywood film. Max Rothbart shifted between fecklessness and frenzy as Erhart; Nicola Kirsch played a basically cold and abstract Fanny Wilton, who most of the time simply stood outside the family circle and expressionlessly surveyed their peculiar relationships, as if she were observing some odd scientific experiment.

Martin Wuttke as John Gabriel Borkman in Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman. Photo: Reinhard Maximilian Werner.

Caroline Peters as Ella often exhibited a distant sense of irony, but could suddenly be driven by her sister into violent reactions, and Wuttke’s clear indifference to her gave her little opportunity to develop any sense of a relationship between them. The most normal member of the company was Roland Koch, as Foldal, although this very normality made him seem as if he had wandered in from another play. His daughter Frida (Liliane Amuat) was somewhat inexplicably given an electric guitar to perform on, not for Borkman, but from time to time to add a certain underscoring to one scene or another. She stays onstage to do this long after Fanny and Erhart have left, so we were apparently to assume that she was (perhaps (inadvertently?) left behind.

The ending of the production emphasized its departure from the original and seemed primarily devoted to tying up loose ends. When Erhart left, Borkman and the sisters rushed about the stage, crying out his name, and the stage curtain for the first time closed. After a few minutes, however, Borkman and Ella emerged onto the forestage for the first time and sat down to talk about their past. Foldal came up to them out of the audience to tell about his injury, and then went off. Although his daughter did not reappear, her guitar continued to be heard behind the curtains. Borkman rested his head on Ella’s shoulder and died. Gunhild came to join them from behind the curtains and Ella informed her that Borkman was dead. Ella repeated the line about Borkman’s story being a comedy, which was the final line of this production. The two sisters laughed together, embraced and struck a pose, Ella holding Borkman’s left hand as he lay on his back beside her. Unseen by the sisters, the dead man slowly raised his right hand, two fingers held up in a V as the lights went out. It is the kind of ironic and somewhat arbitrary reference that would be almost unimaginable on an Anglo-Saxon stage, but in Berlin was cheered by the majority of the spectators. The reference was apparently to Josef Ackermann, head of the Deutsche Bank, who in 2004 fought off major corruption charges, outraged the public by flashing a V sign at his acquittal, and in 2008 was brought up on a retrial and again acquitted. His legal redemption was just the sort of fate dreamed of and unachieved by Borkman, and so the gesture was not entirely inappropriate, although it was totally anachronistic and unacceptable by any standards of realism, consistency, or good taste. In all this, however, it was very German. The audience as a whole greeted this rather bizarre interpretation with great applause, although there were a few hearty boos as well, which the director, who appeared in the multiple curtain calls, acknowledged with a broad smile. Clearly a part of his aim was to achieve such a mixed reaction.

The most popular among the available Theatertreffen choices this year was surely Yael Ronen’s The Situation at the Maxim Gorki Theater, a production almost perfectly suited both to this theatre and its ensemble and to contemporary political and social concerns in Germany in general and Berlin in particular. Usually collaboratively developing work as Yael Ronen & ensemble, Ronen was engaged as resident director at the mainstream Gorki in 2013 after Shermin Langhoff, former head of the Ballhaus Naunynstrasse, took up the reins there as artistic director. The Ballhaus Naunynstrasse was created by and for the Turkish-German community and other “post-migrant” communities in Berlin, and Langhoff has brought her focus on works related to immigrant, ethnic, and postcolonial concerns to the Gorki. Ronen’s own focus on these concerns have made her a natural fit for the theatre under Langhoff’s direction and the synergy has won Yael Ronen & ensemble increasing visibility and a number of major awards. Among these was an invitation to last year’s Theatertreffen for Common Ground, essentially a theatrical report of a bus trip that Ronen took to Bosnia with five German refugees from the former Yugoslavia, as they revisit, physically, mentally, and now theatrically, their former home.

The Situation similarly mixes real life experience with theatrical elaboration, but the focus is now upon the experience of the immigrant in contemporary Berlin. The production has rather the feeling of a political cabaret, divided into eight short scenes, called “Lessons,” each providing a sketch mixing political commentary with comic dialogue and the emotionally charged situation of contemporary immigrants in Berlin. The major “situation,” is the ongoing conflict in the Middle East, of which all of the immigrants are to some degree victims, and from the turmoil of which all have sought sanctuary in Berlin. As in Common Ground, each of the six actors, all immigrants, partly present themselves and their own stories, and partly enact the related stories of others. The central figure, Sergei/Stefan, an immigrant from Kazakhstan, is played by Dimitrij Schaad, a Kazakhstan emigrant, now a German citizen, and their histories are blended together in the production. The first of the “lessons” are in fact lessons in German given by Stefan to a more recently arrived couple, Noa, an Israeli, played by Orit Nahmias and Amir, a Palestinian living in Israel, whose marriage has broken up since their arrival in Berlin. Stefan is attempting to teach them German questions beginning with “W” (Who are you? Where do you come from?) which inevitably lead them into discussions and arguments about “the situation” in Israel and their own “situation,” both political and personal. All the standard clichés about Jews, Israelis, Palestinians and immigrants flow out of this conversion, to the delight and embarrassment of the audience. Other figures complicate the picture in further “lessons”—Laila (Maryam Abu Khaled) and Karim (Karim Daoud) from Palestine and Hamoudi (Ayham Majid Agha) from Syria, who dreams of returning home and resists the naïve if well-meaning attempts of Stefan to help him to “assimilate.” All of the scenes involve two or three persons except for a lengthy and moving monologue by Sergei/Stefan describing his situation in his native Kazakhstan and his escape to Germany. The play moves constantly among a number of languages—German, Arabic, English, and Hebrew, with projected supertitles presenting English for German speeches, German for English ones and both German and English for those in Arabic or Hebrew. This constant heteroglossia adds an important dimension to the recurring question of “Who are you?”

The Situation by Yael Ronen & ensemble. Photo: Ute Langkafel.

The major appeal of the production is clearly the interplay of the gifted company and the tragicomic elements of their “situation” both internal and external. From the point of view of staging, the production is extremely simple, unlike most contemporary Berlin offerings. Designer Tal Shacham has created two small areas downstage of the actual proscenium left and right, which provide a kind of iconic orientation. That on the right represents a street corner in Berlin where Hamoudi sets up his food cart. Although all of the other actors use this area from time to time, no one ever enters the parallel small area to the left, where stands a human-sized plastic inflated green cactus, presumably representing the Middle Eastern deserts that all have left. When the play begins the only scenic element within the proscenium arch is a large blank wooden wall upstage, but it soon pivots to reveal two brightly colored yellow staircases, joined at the top but coming downstage left and right. The rest of the evening’s action takes place either on these neutral staircases or on the Berlin street area to their right.

Whether they dream of a return to their homeland or plan to build a future in Berlin, the company members are united in a hope shared by the audience as well: that “the situation,” whether this refers to the Arab/Israeli relationship, the broader ongoing crisis in the Middle East, or the tensions between the newcomers to Germany and the established population there, will eventually be positively resolved. Lest this seem far too utopian, they recall the fall of the Berlin Wall, the election of a Black man as President of the United States, and the ever-increasing number of women as heads of state in Europe and elsewhere. Such changes give hope that even the seemingly most intractable “situations” can with time be changed for the better.

The last Theatertreffen production I attended was, unhappily, one of the weakest, in a festival that was already not a distinguished one. This was the stage adaptation of a novel from the Kammerspiele in Munich directed by Anna-Sophie Mahler. The novel, Mittelreich, was published in 2011 and was the first novel by Josef Bierbichler, a well-known Bavarian actor and director. The novel looks at nearly a century of history in a small Bavarian town through the lens of three generations of a middle-class family, the Seewirts. Director Anna-Sophie Mahler has studied with Christoph Marthaler and it may be that his marvelous blendings of strong visual theatre and moving musical passages inspired her idea to blend her adaptation of the Bierbichler novel with almost continual musical accompaniment and interludes, primarily from Brahms’ German Requiem, but with touches of Mahler, Orff, and of course Wagner. The cavernous empty stage with its off-white walls, designed by Duri Bischoff, also somewhat suggests the massive Marthaler sets created by Ann Viebrock.

Mittelreich, after the novel by Josef Bierbichler, directed by Anna-Sophie Mahler. Photo: Judith Buss.

Unhappily the similarities end there. The fascinating and ever-shifting tonality so typical of Marthaler’s work, ranging from farce, though almost cloying sentimentality, to deeply moving human emotionality, is all here flattened out into a rather colorless and flat delivery of material which has no clear connection to the almost continual musical accompaniment, primarily provided by pianos in the orchestra pit. Whatever was the nature of the original novel, this two-hour adaptation provides a grim and naturalistic presentation of a family in which there is no understanding or sympathy between parents and children or husbands and wives (though in fact only one wife is shown, in a rather thankless role by Annette Paulmann). Also contributing to the overall flatness of the presentation, aside from the acting style, is that the scenes of family conflict alternate with one atrocity after another. Doubtless life in middleclass Bavaria in the twentieth century was not idyllic, but it is hard to believe that the unfeeling Seewirts can be taken as representative, which is seemingly the aim. I could believe that average Bavarian sons were raised by monks who sexually abused them, or that average Bavarian workers had their delivery vans appropriated by the Nazis to be converted into impromptu gas chambers for schoolchildren, but it began to strain my credulity when the only non-male family member given any extended attention was an intersexual who attracted young girls into the woods for sexual encounters. After three generations of activities of this sort, mostly narrated in flat, unemotional tones, I not only became tired of the crude banality of this Bavarian corruption, but irritated by its lack of any connection, artistically or emotionally, to the Brahms composition alongside which it was developed. The single entrance (totally unjustified in narrative terms) of some thirty members of the Munich Youth Choir to perform a single number was one of the bright spots of the evening, but it only reminded me how much more I would have enjoyed an actual professional performance of the German Requiem than this unfocussed and on the whole ineffective attempt to blend it with unsuitable material.

Thank heaven there were, as always, excellent productions in Berlin outside the Theatertreffen: Thomas Ostermeier’s new production of Richard III with Lars Eidinger at the Schaubühne, Kriegenburg’s marvelous visual fantasy Ein Käfig ging einen Vogel suchen, Karin Hinkle’s inspired rendering of the Labiche face, Die Affäre Rue de Lourcine at the Deutsches Theater, and Castorf’s monumental Judith at the Volksbühne starring Birgit Minichmayr and Martin Wuttke. Productions like this confirm one’s belief in the originality, richness, and daring of the contemporary German stage, even in the face of disappointments like this year’s Theatertreffen.

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is The Theatres of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia with Khalid Amine (Palgrave, 2012).

European Stages, vol. 9, no. 1 (Fall 2016)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Cory Tamler, Managing Editor

Mayurakshi Sen, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 70th Avignon Festival: An Experiment In Living Together by Philippa Wehle

- The 2016 Berlin Theatertreffen: Is Half a Festival Better Than None? by Marvin Carlson

- Introduction au Kunstenfestivaldesarts de Bruxelles 2016 by Manuel García Martínez

- The Fidena Festival, 2016 by Roy Kift

- The Noorderzon Festival in Groningen by Manuel García Martínez

- Review of The Suicide by Steve Earnest

- Spain: Runaway Hits and Ephemeral Memorabilia by Maria M. Delgado

- The Seagull: An Idea for a Short Story by Emiliia Dementsova

- Billy Elliot The Musical at the Hungarian State Opera by James Wilson

- Chorus of Orphans: A Theatre Séance by Poland’s Teatr KTO, Kraków by Jacob Juntunen

- Theatre More Arresting than Ever: A Conversation with Dorota Masłowska by Krystyna Lipinska Illakowicz

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016