Normally around this time of the year, I submit a review of the productions in the Recklinghausen theatre festival, whose theme this year was the Mediterranean. But given the current state of Germany as a whole (predominantly the question of how to deal with the crisis of refugees pouring into Europe from Asia and Africa), and the confused state of theatre in Germany on account of the use of mixed media, and the growing rejection of written scripts in favor of improvised documentary projects and what’s more, adaptations from films and books, I elected to consider an alternative this year and look at the Fidena Festival in nearby Bochum instead.

To begin with, what is Fidena? A dry academic answer would be to say that Fidena is short for the “FIgurentheater DEr NAtionen” or the “Figure Theatre of Nations.” In other words, it’s an international festival of puppet and figure theatre, not only for children but also for adults (one of the earliest visiting companies at the festival was the Bread and Puppet theatre). Founded in 1958, this biennial festival, which is centered in Bochum, is now one of the oldest puppet theatre festivals in Europe.

The main emphasis of this year’s international festival was Asia, and I decided to take the opportunity to confront theatre traditions which I mostly knew, if at all, from books, magazines, or from the odd show I happened to see on my extremely rare visits to Asian countries. Given the impact of ever-growing globalization and the equally increasing xenophobia (if travel does indeed broaden the mind, it seems that it can also equally strengthen our prejudices), it is vitally important for theatre in particular and culture in general, I think, to try to break down deep-rooted alienating responses to what we do not know and emphasize our common humanity. Here, Fidena is playing a particularly important role. The second reason, alongside its global features, is that Fidena also offers a spectacular range of different approaches to theatre from which we, in Europe, might have a lot to learn.

The first show I saw was a story from the great Sanskrit epic the Mahabharata – it’s reputed to be the longest epic poem ever written and is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined – presented by an Indian group called Natana Kairali under the direction of its founder, Gopal Venu, who has revived the dying art of the traditional glove puppet theatre Pavakathakali that came into fashion around two centuries ago in the province of Kerala. Pava means puppet and Kathakali is a stylised Indian dance form noted for its attractive characteristics, elaborate costumes and well-defined body movements, played against a background of music and percussion. The members of the company make their own puppets and travel throughout the country from village to village to perform their stories from the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

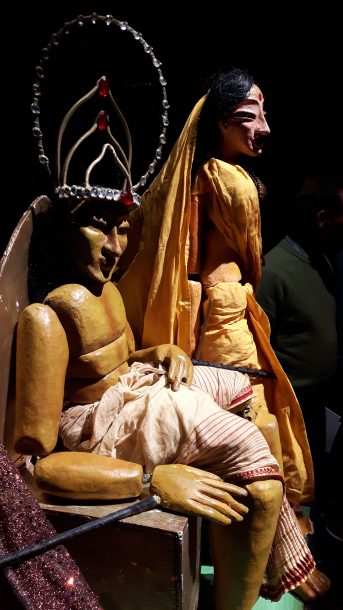

A puppet from Duryodhana Vadham, directed by Gopal Venu, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Roy Kift.

The story of Duryodhana Vadham speaks of the King Yudhishthira who loses his kingdom, his brothers and even his wife in a game of dice. In the subsequent battle between good and evil, good wins out in the end with the help of Lord Krishna. The sixty-minute show for adults and children over eight was an extremely ritualized presentation with extraordinarily beautiful glove puppets. Since it was sung in Sanskrit and Malayalam, Fidena’s director Annette Dabs gave the audience a brief outline of the story before the show began with ritual drumming and the lighting of candles on an almost completely bare stage. What made this performance so moving to me was the respect shown by the performers not only to their puppets but also to the stage and the audience, and their seriousness of approach and their level of concentration. Indeed the discrepancy between the discretely skillful, almost contemplative playing of the bare-chested male performers and the brutal realities of loss, love and war turned the performance into a poignant, almost religious experience in the sense of Peter Brook’s The Empty Space.

Duryodhana Vadham, directed by Gopal Venu, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Pierre-Alain Rolle.

After being thrown headlong into exotic waters, when I came to the surface once more I had to make my way quickly to the official opening performance called Moondog in the Bochum Schauspielhaus. One of the best features of the festival is that it is performed, not only in Bochum but in theatres and non-theatre venues in other towns and cities in the region. This was not so much a puppet show as a performative concert in honor of the legendary street performer, Moondog, whose admirers included many well-known pop starsincluding Bob Dylan and Frank Zappa. Accompanied by his guide dog, the blind Moondog would play an unusual mix of self-written compositions which inspired other composers ranging from Bach to Charlie Parker. It is even said that his work inspired the composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass. By a strange coincidence he spent his last few years in Recklinghausen, just a few miles away from Bochum. The fact that he would have been 100 years old this year was a good reason for Annette Dabs to pay homage to this performer who, judging by the remarks I heard amongst the audience, had clearly also become a legend in the area.

The curtain opened to reveal a white-haired, long bearded, aging, guru-like figure sitting on the floor in front of some home-made percussion instruments. At one side stood a classical string quintet, on the other side was a group of musicians who were more into pop, jazz and Latin American rhythms. Behind them, stretching the whole width of the stage, was a mysterious dark range of ridged hills – a sight that seemed to me to be completely out of harmony with the supposed theme. Why not use a backdrop of Manhattan, for example? The evening was basically a highly entertaining, brilliantly performed showcase of Moondog’s musical innovations. But around halfway through the show the lighting slowly changed and the ridged hills became the silhouette of a gigantic shaggy-haired dog, more astonishingly a puppet dog that moved in tune to the beat. This created a marvelous opening celebration! Filled with the adrenaline of pleasure we were ready to take on the festival and the cornucopia of riches that it had to offer.

But since the festival was not exclusively concerned with Asia, I should like to start by taking a look at a show from Russia. Leningradka, performed by the Moscow State Puppet Theatre, was the story of a girl called Valja, who survived the siege of Leningrad (it began in 1941 and lasted until 1944), during which time according to official estimates more than 1,000,000 people died of hunger. This was clearly a traumatically painful experience for the Russians. It was also a sensitive subject for many of the German audience because Leningrad had been besieged by Nazi German forces.

When Valja’s father is called up to serve at the front, he promises his daughter that the house spirit, a goblin called Domovoi, will protect her and her mother while he is away. Throughout the eighty-five minute show, Domovoi comes to the rescue on several occasions, negotiating food from a greedy rat, managing to light a fire to save the family from freezing to death, and even rescuing a load of mandarin oranges from a truck that had sunk in the ice. The production not only used live puppets but also cartoon puppet films and excerpts from documentary films projected onto a large screen in the middle of the sparse setting. In the beginning, I thought that the screen would eventually be hoisted upwards to allow the puppetry to take place in the centre. But it soon became clear that film and cartoon effects would play a larger role than I had expected. Each in its own right was very impressive. But put together, none of them seemed to merge organically into a satisfying whole. The old black-and-white documentary films were fascinating for adults. But they then jarred with the little goblin that came straight out of shows for children. And whenever the puppets were insufficient to tell the story, the show fell back on multi-media to move it along. I can imagine that the show’s creators thought that each form of presentation would enhance and enrich the others. But for me the different approaches never merged into a satisfactory whole. This was further aggravated by the fact that the show ended in a romantically cute and kitschy atmosphere with the reunion of the “back-from-the-dead” father and his daughter, underlined by music played with heavy Slavic pathos. True, it was all very serious, but where was the tragedy, where was the suffering?

A scene from Leningradka, performed by the Moscow State Puppet Theatre, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: The Fidena Festival.

War raised its ugly head once again in a one-man show from Israel called Plastic Heroes (concept and performance by Ariel Doron). The Fringe Theatre in Rottstrasse 5 in Bochum is little more than a vaulted room beneath a railway viaduct, with an empty concrete floor on the performing side and three or four rows of variegated seating on the other. The stage was taken up by a long wide table behind which Doron moved his puppets. But to define them as puppets would be quite misleading, because they were not so much puppets in the traditional form but children’s toys. These puppets were plastic, almost all of them entirely ready-made commercial objects in the manner of soldiers and weapons. Thus, Doron built a long protective wall around the table behind which he patrolled a single plastic soldier, of whom we could only see the top of the head, back and forth, and back and forth. The monotony of soldiering could have hardly been more graphically portrayed. And when the soldier finally decided to take a break, it was to pull up pornographic images on his cell phone which he used to satisfy his lust in private. Subsequently, we saw a wound-up soldier, complete with rifle, flat on his stomach moving across the table on his elbows and knees, ready to shoot some imaginary victim. But when it came to the crunch, the soldier was suddenly overtaken by fear and refused to take the orders from his superior officer, after which his fantasy moved on to a sex game with a Barbie doll. This was all very amusing and, in a vague way, shocking had it not been so childish. But, considering that the show came from Israel, a divided country full of uncompromising brutality, I had expected much more than the obvious statement – which we knew from the start – summed up with the hit song “War! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing!”, performed in the end as if we were all in a disco together. It was all rather self-congratulatory and in the end, the final impression consisted more of simple child’s play than horrific reality.

A moment from Plastic Heroes, executed by Ariel Doron, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Anael Resnick and Yair Meyhuas.

Let me go back to Asia for the moment. The biggest audience hit of the festival was played out in the huge blast hall of a defunct iron and steel works in Hattingen. And what a spectacle it proved to be! The Saigon Waterpuppet Theatre from Vietnam is one of the country’s national treasures. Its stage consisted of a huge tank of water (35,000 litres!) behind which was a curtain of green bamboo rods beneath what looked to be a red Vietnamese palace. To the right of the set was a group of five musicians, including a singer, playing on traditional Vietnamese instruments. Puppeteers were nowhere to be seen. They were hidden behind the bamboo rods and they manipulated their puppets either directly by means of long rods beneath the water or, when it came to groups of puppets, by pushing them out beneath the water on heavy machinery on wheels. Hence, all we could see throughout the show was either figures that seemed to be independently popping up out of the surface, or floating in on the surface. Following traditions the 50-minute-long story consisted of episodes from the everyday rural life of Vietnam, without foregoing mythological figures like a unicorn, dancing fairies and the ubiquitous Asian dragons snaking to and fro in glorious rhythm. I was particularly taken by the swimming figures (children or adults, or both?) frolicking in the water, leaping above the surface and somersaulting high in the air like porpoises before landing back once again, and the puppet musicians standing thigh deep in the water and performing in unison with each, and then with all, of the musicians at the side of the stage. The Waterpuppet Theatre ostensibly goes back as far as the twelfth century. It was in the danger of dying out for a time and has only been revived in the 1980s. It was all great fun, impressively played with great dexterity. As an additional bonus, we were permitted to go backstage after the show to view the machinery, and try our hand at playing the traditional instruments.

A moment from the show by the Saigon Waterpuppet Theatre, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Roy Kift.

The chance to get an insight into the practical work involved was one of the best features of the festival. It was especially useful during a performance of the Lanka Dahanam Shadow Theatre. The particular genre of Tolu Bommalata in Andhra Pradesh (India) is one of the oldest existing art forms in the country. The players stand behind a huge white screen where they manipulate large leather puppets, whose shadows move backwards and forwards in unison with the rhythms, the music and song. From the audience’s side these figures dance in and out of perspective like dream figures emerging from a (literal) shadow world, into which they constantly disappear once again. The story of Lankha Dahanam is taken from the Ramayama and relates to the kidnapping of the wife of Lord Rama, Sita, and her attempted rescue by Lord Hanuman. After the attempted rescue, Hanuman is captured by Ravana and his tail is set on fire, whereupon, Hanuman sets the whole of Sri Lanka on fire. Although the nuances of the story were difficult to follow, this was more than compensated for by the fact that, during the show, the audience memberswere invited to leave their seats and go behind the screen to observe the performers in action.

Behind-the-scenes snapshot of the shadow theatre Lanka Dahanam, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Pierre-Alain Rolle.

The tale of the Hindu god Rama was repeated in an utterly different form by Anurupa Roy’s Katkatha Theatre, also from India, with a show called About Ram, which utilised beautifully made, full-length wooden puppets. Here, Rama covers his face with the mask of Hanuman, and in the guise of a monkey, he travels across the ocean to fight for and win back his beloved Sita. Normally, this would lead to a conventionally happy ending. But the story has a more intriguing end. Having regained his love, Rama is not sure whether he wants to keep her or take another woman as his consort, like many men in positions of power! The puppets were beautifully crafted, and there was a particularly spectacular scene where Sita’s captor attempted to rape her by unwinding her long yellow dress from her body, and Hanuman countered this by wrapping her back again.

A moment from About Ram, directed by Anurupa Roy, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Roy Kift.

Staying on the course in Asia, we were treated to a multi-media dance show from Japan titled Match Atria Extended. The title is a combination of the two words, “matcha” (the Japanese tea ceremony), and “atria” (the blood collection chambers of the heart). In other words we were invited to witness an intimate ceremony of the heart. The audience was strictly limited (to 32) and before we entered the stage area, we were led formally into a narrow corridor and asked to sit on benches in two rows of sixteen people each. We were then welcomed by two solemn “air hostesses,” and given instructions by two solemn “air stewardesses” on how to don special 3-D spectacles and headphones after arriving at our seats where we sat in groups of eight, overlooking the playing area. What followed was a mesmerizing series of three-dimensional video projections rather similar, I dare to guess, to an LSD trip; a pulsating universe of forms and colors swirled around a phenomenally fine Japanese woman dancer, Yui Kawaguchi, to the magnified sound of the dancer’s heart beats. I can’t begin to say what this was about. It simply was…out of this world. And I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

Yui Kawaguchi in Match Atria Extended, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Kunuhira Fukumari.

Finally coming back to Europe, I decided to look at a puppet show for the very young (meaning from two to four year olds), because I wanted to see how a company would meet the challenge of telling a story that would be comprehensible to such an age group. The Lamb that fell from Heaven was presented by the Naivni Divadlo Company from a town called Liberec, once the home of a thriving textile industry in the north of the Czech Republic. The Naivni Divadlo Company was founded in 1949 and is one of the leading puppet theatre companies in the country. The play, inspired by motifs from a German children’s book by Fred Rodrian, tells of a little girl who catches a fluffy white ball that falls from the sky, and wants to help it find its way back. They pass a fairground and make friends with a tightrope dancer and a boy who runs a shooting stand. Circus people, including their fat director, also try to help. With the aid of a large cannon gun, a pyramid of acrobats and a number of balloons they finally manage to get the fluffy white “lamb” back up into the sky. The children were seated on three sides of a specially constructed stage with a “revolving dias” in the middle. This was especially useful, for it allowed the children on all the sides to get a good view of the passing puppets, and slowed down the action enough so that they would have the time to grasp who or what it was about. Above the stage was a transparent canopy (the sky) with a hole in it on which the fluffy ball could move and eventually fall to the earth. The puppets and objects were moved by hand by three players, accompanied by a musician, in full view of the audience. Some of the objects, like a large fire engine with an extendable ladder, had been bought. Others, like the characters, were made by the company. The narration worked perfectly because the company understood that the children had to have an emotional identification with the main puppet figure and its relationship to the “lamb”, and also because the objective – in Stanislavskian terms, the “action” – in the story was so clear – to ensure that the lamb returned home safely, or in metaphorical terms, that the cloud was returned to its place in the sky. This made it possible for the performers to be clear about the means used to achieve this aim, and the problems involved in trying to do so. Thus, the very young audience was able to truly “follow” the story in complete absorption. I was too. I was fascinated by the simplicity of the means used, and the imaginative way the company succeeded in making the 45-minute story truly theatrical. This was an object lesson in how to adapt a theatre show from a book without resorting to multi-media gimmicks or out-front narrative. As a bonus, after the show, the children were invited to join the cast and the puppets and try things out for themselves.

A moment from The Lamb that fell from Heaven, performed by the Naivni Divadlo Company, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Juan Carlos Vanegas.

The Lamb that fell from Heaven was presented in the studio theatre of the Grillo Theatre, the city playhouse in Essen, the largest city in the area, around 10 kilometers west of Bochum. Ninety minutes later, I turned up at the main auditorium for a glorious piece of comic theatre for adults and children from the age of 10 upwards. The title of the show, by Theater Drak (also from the Czech Republic) was George Méliès’ Last Trick. Anyone with a vague idea of the history of cinema will immediately recognize the name, Méliès, and have a good idea of the theme of the one-hour show. Georges Méliès (1861-1938) was a pioneer illusionist and filmmaker who revolutionized the use of special effects, including splicing, dissolves, time-lapse photography, multiple exposure and coloration. During his lifetime be made over 500 films, the best known of which are probably A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Journey (1904), both of which might be classified as early examples of science fiction movies. Following an initial success which made him a rich man, he was the victim of false investment and commercial pressures and was declared bankrupt. In 1921, he broke with the film industry completely, and eked out the rest of his life in poverty, despite being increasingly recognized as a legendary filmmaker. He died of cancer in 1938.

The show takes the dying Méliès as its starting point. Emaciated, white-faced and red eyed, this grotesque clown – not played by a puppet but by an actor, as were all the characters in the show – is sitting in his nightgown behind a table under the supervision of a strict nurse who enters the room to see how he is. Whilst she is out of the room, his inventive capacities come to life and he wallows in a series of astounding illusory tricks. But as soon as she returns, he instantly reverts to his role of a feeble, sick, helpless, obedient patient. The first time the nurse leaves the room, after insisting he eat the meal she has prepared for him, he opens up the side flaps of the table and begins to draw. Simultaneously, a video appears behind him to show what he is drawing and what he is imagining – here, it is a trick between two men where a dove emerges from a top hat to fly from one to the other. But the most spectacular tricks take place on stage, where skeletons arrive, people are pushed up and down the plughole of a sink, Méliès’ hands double to four and then six – two of which instantly disappear -, suddenly he has no head, etc. I could go on for pages to recount the firework succession of hilarious illusions and slapstick tricks, all played out against a musical background of clarinet or piano in the classic silent-movie vein. This was quite one of the most entertaining theatre shows I have seen in a long time. Were the company to get rid of its very few Czech headlines and substitute them with English, I am sure this would be a sensational success in the West End and on Broadway.

A scene from George Méliès’ Last Trick by Theater Drak, the Fidena Festival, 2016. Photo: Theater Drak.

Under its director, Annette Dabs, the Fidena festival has grown from strength to strength over the years, as can be seen from the fact that this year’s nine-day festival presented 30 companies and performers from 11 countries. All in all, 6,300 spectators visited the 40 shows, of which 21 were completely sold out. And, most moving of all, the festival even managed to cater for the many refugee children in the region with a special touring show in Arabic played by the award-winning Lebanese Puppet Theatre group based in the Khayal ( meaning ”imagination”) education centre in Beirut. Let Merjane Sleep tells of a young Prince Merjane and his encounter with Scheherazade, after which he realizes that life is beautiful in all its stages and decides to enjoy every moment as it arrives. I wasn’t able to see it myself because, quite rightly, the performance was exclusively reserved for the refugee children, and to have allowed an external audience to view the proceedings would have reduced the refugees themselves to a part of the show.

Annette Dabs, Director of the Fidena Festival. Photo: Simon Bauks.

At the start, I asked what Fidena was and gave you the dry answer. Now comes the fantastic (and theatrically true) version as published by the festival itself.

Fidena is Fish/Meat/Dish/Eat

Veggie/Edgy/Dirty/Flirty

Cool-ish/Foolish/Much too clever

Never ever/Loud of course/Fidena roars

Fidena’s real/A gourmet meal

Sometimes lousy/Often frowsy

Dinner jacket?/Wouldn’t back it!/Couldn’t hack it

Fidena/Tops the lot/Our beauty spot

Virtuoso/Amoroso/Animating/Captivating/Motivating

Elevating/What a fizz!/Fidena is

Annette/Can’t be better!/Welcomes all/What a ball!

International/Quite irrational/Up and down/On the town

In and out/Roundabout

Hungry/Angry/Feisty/Feasty/Thirsty

Wine/is fine/Whisky’s/Risky

Beers/Queers/Puppeteers/Bring them here

Fidena/No brainer!/Proudly rowdy/Never dowdy

Laughing/Crying/Barfing/Sighing

Sweating/Petting/Loving/Hating/Dating/Mating

Manipulating!

Fidena’s/Best!

Time to rest

After that I’m almost tempted to ask, “Who needs a review?”

I can’t leave, though, without returning briefly to “proper” theatre. At the start of this article I talked about the fashions that are currently reigning in German theatre. This year, to celebrate its 70th anniversary, the Recklinghausen Festival invited the legendary theatre director and current Intendant at the Berliner Ensemble, Claus Peymann, to give a talk on contemporary German theatre. He did so in the form of a mini-drama, a self-styled last will and testament in which he outlined eight major themes which are matters of concern to him at the moment. These may be summarized as follows:

Literature is in danger – literature is retiring from the scene. Plays are no longer being produced. Instead, every second novel is being dramatized in every film scenario. Banishing literature from the theatre is perhaps our greatest danger. My director colleagues believe that they are themselves the greatest poets. A frightening misjudgement.

1. A secret is in danger – when an actor plays Richard III he doesn’t believe in the character any more. Instead he cracks a joke about Richard’s knife: “Oh shit! It’s blunt.” The audience laughs, but the fact is that the actor is denouncing his character which is a dangerous tendency. Our real weapon is the secret of transformation.

2. The elimination of skill – actors don’t know how to speak any more. They are unable to project to the end of the auditorium. It is a catastrophe that young actors don’t learn how to speak when they’re at drama school. Instead they learn how to use micro ports. Theatre is getting confused with television. We are surrendering our uniqueness as theatre people.

3. In praise of the province -: theatre comes from the provinces. The Royal Shakespeare Theatre is in Stratford. I always wanted to make theatre for local people who could get home after the show by car, but this is now considered almost indecent. Instead of that there are now groups that play this week in New York and next week in Paris. The theatre needs a local venue for its productions, like a local family. Globalisation is the death of theatre.

4. The addiction to the “new” – journalists have long given up on the theatre. Newspaper reviews are shrinking to the minimum. They only function when something is regarded as completely new. The theatres are themselves at fault. Recently the head of the Berlin Theatre meeting remarked with praise: “Not a single show is played as written on the page!” So what are the pages for? Tell that to Simon Rattle! (Rattle is the current chief conductor of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra.)

5. Theatre is a museum! So what? Some people say my theatre is a museum. And? The following words used to stand over a theatre – “To the true, the good and the beautiful!” Is that old-fashioned? Spread the truth! Ask where to find the good! In politics, in society? This vision of art is eternally important in a society in which ethical positions have been completely destroyed.

6. Language and imperialism – is it imperialism when Soviet tanks stand on the borders of Germany? No. Imperialism is when your own culture goes down the drain. Every second play in the German repertoire has an English title. We’re turning ourselves into slaves. We think it chic when internet language dominates the German stage. If we continue as we are, German will be turned into a dwarf language. We are German because of our language, not because of Krupp or the Bild-Zeitung (the most popular and sensational newspaper in Germany).

7. On this year’s festival in Recklinghausen – I don’t like themes, be it the Mediterranean or the South Baltic Sea. Maybe you’ll take up East Westphalia at sometime! It’s all getting random and this is not particularly forward-looking. Nonetheless, my compliments. The best actors are still coming here.

You may not agree with everything he has to say, and in the German theatre world Peymann is widely regarded as a rather crusty conservative, but speaking as a concerned Englishman living in Germany, I think his comments are worthy of respectful consideration.

Roy Kift is a British playwright living in Germany. His holocaust play Camp Comedy is still in the repertoire of the Helena Modjeska Theatre in Legnica, Poland. A Czech premiere is scheduled for February 2016. His latest play Eden’s Garden is about the role of Great Britain in betraying Poland to the Nazis and the Russians during and after the Second World War (the British foreign secretary at the time was the later Prime Minister, Sir Anthony Eden).

European Stages, vol. 8, no. 1 (Fall 2016)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Cory Tamler, Managing Editor

Mayurakshi Sen, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 70th Avignon Festival: An Experiment In Living Together by Philippa Wehle

- The 2016 Berlin Theatertreffen: Is Half a Festival Better Than None? by Marvin Carlson

- Introduction au Kunstenfestivaldesarts de Bruxelles 2016 by Manuel García Martínez

- The Fidena Festival, 2016 by Roy Kift

- The Noorderzon Festival in Groningen by Manuel García Martínez

- Review of The Suicide by Steve Earnest

- Spain: Runaway Hits and Ephemeral Memorabilia by Maria M. Delgado

- The Seagull: An Idea for a Short Story by Emiliia Dementsova

- Billy Elliot The Musical at the Hungarian State Opera by James Wilson

- Chorus of Orphans: A Theatre Séance by Poland’s Teatr KTO, Kraków by Jacob Juntunen

- Theatre More Arresting than Ever: A Conversation with Dorota Masłowska by Krystyna Lipinska Illakowicz

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016