By Anton Pujol

“Exhaurides les localitats” (Sold out) became a ubiquitous sign across most venues for performances from this year’s Barcelona Grec Festival. The 46th edition of the annual festival was highly anticipated because once again it was under the direction of Cesc Casadesús. This year, the Grec, in just a little over three weeks, offered eighty-six shows. That translated into over 165,000 tickets with purchase prices that ranged from 10 to 30 euros. Tickets sold jumped by 16% from the previous year, with almost 115,000 spectators driving attendance levels better than even pre-pandemic years (Garcia). As usual, the festival programmed a vast range of performances for every genre and all ages: from dance and theatre to circus and hybrid performances in museums and to other spaces throughout the city. These included the Teatre Grec, the Teatre Lliure, the Teatre Nacional, and the Mercat de les Flors which hosted mostly dance performances. Unfortunately, most shows were performed concurrently, thus it was impossible to attend everything. Nevertheless, here is a summary of performances grouped by genre and outlined roughly in chronological order.

Historically, dance has occupied a central part of the Grec and it has gained even more prominence in recent years. The Festival opened with Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) directed by Emily Molnar and offered three pieces under the title The Poetic Body. It included How to cope with a sunset when the horizon has been dismantled by Marina Mascarell, Bedroom Folk by Sharon Eyal and Gai Behar and One Flat Thing, reproduced by William Forsythe. Mascarell’s choreography used Richard Wagner’s Das Rheingold, among other compositions, to represent an awakening of bodies that tried to negotiate their physical shortcomings against a rigid environment represented by oddly shaped blocks spread across the stage. Eyal and Behar’s segment was a mixture of classic and modern dance, starting with a very rigid formation of six dancers, punctuating every single move with every part of their body. The dance progresses from the tight initial formation and changes with the dancers going their different ways. Nevertheless, the dancers perform perfect synchronization and combined with the original music by Ori Lichtik, the result is a mesmerizing piece throughout its twenty minutes duration. The lighting designed by Thierry Dreyfus created breathtaking moments. An example was the dancers’ shadows being reflected on the original, vast, stone of the Teatre Grec, which resulted in a gorgeous platonic effect. The evening closed with the already classic, violent and raw performance by Forsythe. Twenty metal, large tables are placed on the stage where dancers perform Forsythe’s energetic choreography in between, on top and under the tables and in every available inch of the cramped space. Forsythe’s masterpiece from 2008 seemed even more aggressive, if that is possible, this time around. Bordering, at times, on gymnastics, the dancers draw impossible physical sequences where the pain is not metaphorical but visible. In all, a triumphant opening to the Festival.

Lali Ayguadé created, choreographed, and danced Runa (Ruin) where she traces the vicissitudes of a couple. Ayguadé structures her piece around a series of short scenes, sometimes just seconds, punctuated by blackouts. Alongside her partner, Lisard Tranis, they start out as a happy couple. They dance to Edith Piaf, played on an old record player or they watch TV mouthing, repeatedly, to the words of James Stewart and Donna Reed in the “Do you want the moon?” scene from Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). There seems to be an ominous, apocalyptic wind roaming outside their apartment. Soon, however, the choreography turns darker and more violent. At one point she seems to be pregnant, but the audience can only guess since nothing is ever given an explanation. Mysterious music plays throughout the piece as if some kind of event is keeping them from going outside. Are we still trapped in pandemic times? As translated into dance, the fear seems to take hold of their bodies forcing them to fight, as if trying to flee from this “ruin” of a relationship. The audience is also uncertain if the ruins are in the past or the present, whether they are fighting for survival or to hold onto a memory that is slowly fading for both. Surrounded by objects that could define a relationship (a couch, a fridge, records, clothes), Ayguadé and Tantris’ duets turn two bodies into one, they respond to each other, they melt into one another but the same elements that previously delineated a loving relationship are now destroying it. Last year, after Kokoro Iuanme, Ayguadé completed her trilogy with Hidden, where she poignantly unraveled a family’s past. This time, Ayguadé goes further not only in materializing the pleasures and dangers of being in a relationship but also as a powerful creator of emotions who is not afraid to push our conception of what theatre and dance can accomplish.

Another awaited performance was Larsen C by the Christos Papadopoulos Company at the Mercat de les Flors, and he did not disappoint. Larsen C refers to the Norwegian Carl Anton Larsen and the ice shelf that he sailed around in the Antarctic Peninsula before they split into two: Larsen A and Larsen B. Due to global warming, A collapsed in 1995 and B in 2002. Larsen C separated from the main body on July 12, 2017, and is quickly melting away. A strange origin for a choreography that Papadopoulos delivers brilliantly. Divided into two parts, his choreography starts out pitch black and through shadows we see faces and bodies across the stage. Six dancers all dressed in shiny black clothes start moving alone, with crisp movements. Soon they form duets, trios and all kinds of formations that weave into groups like molecules trying to find a space where to connect in a rapidly disappearing environment. The movements are repetitive and played in small gestures. The dancers move their arms as if they were wings or expanding as they glide on the stage. Perfectly in unison, they work themselves into a frenetic rhythm accompanied by the punctuating music of Giorgos Poulios. And then it all stops. A brief, simple epilogue follows. A light effect that turns the dancers’ torsos and extremities into peaceful shadows, as if seen through the beams of a lighthouse. It was a mesmerizing effect to conclude an unforgettable evening.

Larsen C by the Christos Papadopoulos Company. Photo: Grec 2022 Festival de Barcelona.

While Papadopoulos’s choreography received a thunderous ovation on the large stage of the Mercat de les Flors, Nazareth Panadero & Co also sold out the tiny studio upstairs. Under the title Vive y deja vivir (Live and let live) Nazareth Panadero presented Two Die For and Mañana temprano (Early tomorrow). Panadero joined Pina Bausch’s Tanzteater Wuppertal in 1979 and the imprint of the German artist is clear on the Spanish choreographer. She choreographed both pieces with Michael Strecker, alongside Adolphe Binder and Meritxell Aumedes for the second one. Panadero danced both duets with Damiano Ottavio Bigi, another Wuppertal member. Both works are about the impossibility to communicate effectively. At one point, Panadero shouts “chaotic past, delicate present and dubious future” and the beautiful lines that both dancers form with their bodies are soon interrupted by reality in the form of a multitude of objects laying on the stage. Their bodies are yearning to be fluid, but they keep failing.

Mañana temprano by Nazareth Panadero. Photo: Grec 2022 Festival de Barcelona.

One of the most anticipated performances of the Festival was La Veronal’s Opening Night. Although the show had already premiered last year at the Teatre Nacional, with only 50% capacity due to Covid measures, it really felt like an opening night. In the last five years or so, La Veronal, with Marcos Morau at the helm, has achieved a prominent place in the European contemporary dance scene with works such as Sonoma, Pasionaria or Voronia, among others. Loosely inspired by John Casavettes 1977 film, Morau’s Opening night is a love letter to the world of theatre from the beginning when Mònica Almirall takes what seems to be her final bows in front of the lowered curtain to the acclaim of the audience. She thanks them and thanks everybody else involved in the theatre and in the play she is being applauded for. Then the action shifts and two bodies emerge from the prompter box and interrupt her. Their duet, a sort of battle, contains Morau’s movement trademarks: angular positions, bodies intertwined with endless imagination, and rhythmic patterns of classical and contemporary dance language taken to impossible extremes. Once the dancers return to the prompter box, the curtain finally rises. On stage we see a massive backstage, painted black, with two doors that open, probably, onto the fictional stage where the play has finished. The area is full of grids, vents, pulleys and all the typical elements that theater audiences are not supposed to see. Dancers appear from all places imaginable and perform their routines before they disappear once again. And then, magically, the massive backstage wall moves to the back of the stage revealing the wings, the crossover space, and the fly rails of the cavernous stage of the Teatre Nacional. It was a gasp-inducing effect designed by Max Glaenzel. The fly rails even perform their own choreography as they travel up and down. The five dancers keep performing routines that border on the sublime or comedic depending on the moment. Morau’s choreography combines athleticism, contortionism, classical and contemporary movements creating a metatheatrical performance that is more theatre than dance but, whatever the definition of what Morau’s piece is, it sure is indelible for the audience. To witness Morau’s multifaceted approach to what a performance might encompass is a joy to behold. It created an emotional effect for an audience that knew that La Veronal’s Opening Night was a once-in-a-lifetime moment. It is surprising, to say the least, that none of the local public theatres have booked the company for a longer period of time since they are the critical and audience darling of the moment, and rightfully so.

Opening Night by La Veronal. Photo: Grec 2022 Festival de Barcelona.

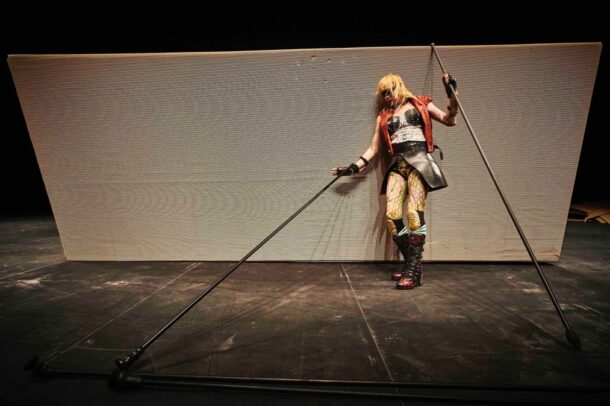

Two other companies offered plenty of “effects” for audiences to experience with their performances: Compagnie Non Nova—Phia Ménard with La trilogie des contes immoraux (pour Europe) (Trilogy of Immoral Tales [For Europe]) from Belgium and Tanya Beyeler and Pablo Gisbert’s company El Conde de Torrefiel with Una imagen interior (An Interior/Inside image). Both companies have developed their very own brand of what performance is and they both have devoted followers. These two companies fully embrace postdramatic theatre: sophisticated and elaborated visuals combined with very little narrative for the audience to make sense of the proceedings on stage. Ménard’s Trilogy, a punishing three hours without an intermission, is architecturally speaking built around three (Maison Mère, Temple Père, and La Rencontre Interdite) sequences that shed light on the world that we have inhabited. At the beginning, Ménard herself, in a punk-warrior outfit, stares at the audience as they walk in. On the vast stage, there is a large sheet of cardboard on the floor that she struggles to cut and put together. It takes her over an hour to build what, towards the end, looks like the Parthenon. Then massive amounts of rainfall onto the weak structure destroys it completely. The destruction is followed by a thick plume of smoke engulfing the stage and the audience. After it clears, the audience seems to be in an ocean (?) presided over by a massive windmill-like structure. Slowly, it is dismantled, and it becomes the base of a tower (Babel?) that is put together by five slave-like creatures. These beings follow unintelligible directions of Inga Huld Hákonardóttir, a priestess/dictator that screams and sings in different languages. The structure being built is, to the audience, a very fragile, terrifyingly dangerous and, seemingly unstable platform for the slaves to stand on; but inexplicably, they do. At the end, a mammoth house of cards has been constructed on the backs of the slaves while the priestess looks in awe of “her” achievement, an apt metaphor for much of modern history. The closing chapter of the trilogy takes place in near darkness when we glimpse the sight of a body coming down from the top of the tower and sluggishly descending, sliding, falling, and dropping to the floor. It is Ménard’s ravaged, transgendered, exhausted body finally laying down in front of a translucent curtain that covers the tower. Painstakingly, she gets up and starts painting the curtain with black and broad brushstrokes. And then she leaves us to make sense of what we have witnessed. There is a sense of loss and pain, of unrealized hopes with devastating results for humanity. This feeling is represented in Ménard’s transformed yet yearning body. It is a body that hopes for a better future and looks to forget our toxic history so that it can strive for a better reality. Regardless of the reading, whether political or personal, that audiences choose after watching Ménard’s trilogy, the truth is that her astonishing theatrical imagination is second to none.

La trilogie des contes immoraux by Phia Ménard. Photo: Grec 2022 Festival de Barcelona.

Una imagen interior was also catalogued by the Grec Festival as a hybrid performance. Beyeler and Gisbert’s work starts with two museum workers hanging a large canvas of a Jackson Pollock-like painting. The supertitles inform us that it is a 36,000 years-old fake work being exhibited in a National History Museum somewhere in the world. The visual segment ends and then we are at a very bright supermarket, followed by a strange planet with mushroom-like structures (to somehow define them), that walk around. Then people appear, and they seem to enjoy themselves. Soon after, they all start painting a work very similar to the one at the beginning of the play. The supertitles will play a key role throughout the proceedings. While they provide information about the characters and the spaces, they consist of only minor details that do not amount to a coherent narrative, far from the intention of the creators. At the beginning, the supertitles inform us that “everything that is about to happen on this stage is fiction, it is all a mise-en-scène, a performance”. They also add that, upon admiring the fake painting, viewers experience an authentic emotion: “the brain is such a strange machine, it is capable of producing a true emotion from something that it is objectively false.” Imagen clearly lays out its themes for the audience. From there, the audience is invited to question their ideas regarding fact, fiction, verisimilitude, theatre, stage, reality, objectivity and subjectivity. The spectator’s task is not that different from what the actors are doing on stage: observing, thinking and trying to decipher their surroundings. It is a visually striking production that wanders around like those customers in that imaginary supermarket. It could be a reflection on our reality, their way to challenge old ways of understanding theatre; a risk that might be stirring for some and mind-numbing for others.

Another interesting hybrid piece, on paper, was Gardien Party by theater director Mohamed El Khatib and visual artist Valérie Mréjen, two renowned French artists. Their piece was the result of observing museums, their visitors and their Gardiens, or guardians. They are the silent people that visitors often ignore who watch over a museum’s works. El Khatib and Mréjen gathered six actual guardians who work in museums (such as Louvre, Moma, Hermitage and others) and had them share their experiences with the audience. This included their day-to-day work, their lives and responsibilities but, mostly, their pet peeves regarding the visitors. Chief among their irks was answering the most often asked question: “where is the bathroom?” Gardien Party was performed in the Sala de la Cúpula at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC), next to the large Joan Miró mosaic, an ideal setting. The guardians later chose their favorite work of art and discussed it with the audience. However, an actual guardian from the MNAC soon requested them to leave since the museum was about to close. The night shift introduced us to another guardian, Jean-Paul Sidolle, a professional dancer who suffered a career-ending injury and become a guardian. Once everyone is gone, he dances across the large rooms of his museum. It was a touching ending to a work that gave voice to figures that are usually ignored.

Two of the most important European directors bookended the main stage of the Teatre Lliure-Montjuïc: Thomas Ostermeier with his 2012 production of An Enemy of the People by Henrik Ibsen and Romeo Castellucci’s Bros. The Schaubühne production of Ibsen’s classic has been seen around the world but an eager audience made it feel as if it was brand new, even though this version felt already old. Adapted by Florian Borchmeyer, the 1882 Ein Volksfeind /An Enemy of the People tells the contemporized story of Dr. Stockmann’s discovery that the water in the new town spa is contaminated and must be shut down immediately, sinking the town’s economy for many years to come. Ostermeier’s coup de théâtre takes place when Stockmann defends his actions to go public in front of the townspeople where he will be condemned as an enemy of the people. Instead, the German director turns on the lights of the theatre, and Stockmann pleads directly with the audience, completely dismantling the fourth wall. After his anti-neoliberal speech, the doctor invites questions and comments from the audience and interacts with them, as do other characters, expressing counterpoints when necessary. The back and forth lasted way too long and it ended with Stockmann being pelted with paint balloons before revealing the ambiguous ending. It might not be fair to review a production that is already ten years old since what might have been described as radical and transformative upon its opening, now, unfortunately, reads as wearied.

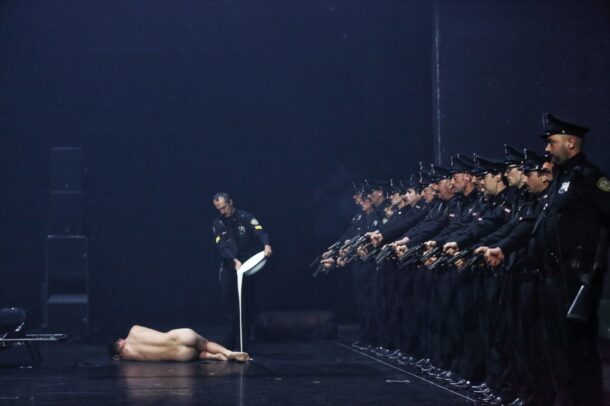

With Bros, the Italian director filled the stage with over 30 menacing men dressed as policemen. From the beginning, with a large surveillance device that doubles as a machine gun, the audience knows what to anticipate. But, the early brutal sound (earplugs were given at the entrance) and the dominating darkness of the stage is interrupted by the contrasting presence of the prophet Jeremiah. He speaks in an indecipherable language (the translated text was part of the program that the audience should have read before since no supertitles were offered). Jeremiah’s long “flee from Babylon” warning remains difficult to understand as are the Latin sentences that two of the policemen flash to the audience: “You cannot tell the past what to do”, “You need to come to an understanding with the dead” and so on. The policemen, according to the program, are not professional actors. They receive orders via an earpiece, and they follow them throughout the play. It is impossible to describe what Bros is about. It oscillates between comedic moments reminiscent of Keystone Cops and horrific moments, such as the unwatchable torture of a naked young man or a waterboarding scene. At one point, a puppet-like dictator addresses the cops in a military setting. Throughout the play, there are random appearances of enormous images of classic monuments, animals and even Samuel Beckett. Also, the policemen reenact classical paintings such as Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson or Goya’s Fusilamientos. During the brisk ninety minutes, the “bros” arrange themselves in non-stop formations, constantly moving and, at one point, descending into the audience and menacingly watching over them. Then, they return to the stage, suffer a seizure and die. At the end, a little kid, all dressed in white appears under the banner “De Pullo et Ovo” (Chicken and Egg). Maybe it symbolizes the need for society to go back to a more innocent and pure time, such as Jeremiah warned us at the beginning. However, Castellucci’s reads like a dramatization of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, a state of surveillance from which we cannot ever escape. Regardless of the grim proceedings on stage, Castellucci, along with his team, achieves moments of rare beauty with painful images that will likely remain with the audience. It is a tough, but necessary, experience.

Bros by Romeo Castellucci. Photo: Grec 2022 Festival de Barcelona.

Contemporay Catalan theater was well represented across different venues in town. At Teatre Akadèmia, Marc Rosich’s Isidora a l’armari (Isidora in the Closet), the story of a closeted tailor and his infatuation with Isidora Duncan during the pandemic, was both funny and touching. It delineated a wonderful character without condescending or resorting to cheap tricks. Skillfully played by Oriol Guinart and Jordi Llordella, Rosich’s play should have a long commercial life. At Sala Beckett, LLàtzer Garcia Al final, les visions (At the end, the visions) created an effective play around the events that had taken place in a nearby house; events that will forever haunt Àlex (Joan Carreras). At Teatre Lliure-Gràcia, Fàtima by Jordi Prat i Coll dramatized the eponymous character’s descent into the drug-ravaged hell called Raval, a rough neighborhood in the middle of Barcelona. The play is structured around scenes where Fàtima meets a dog-quoting Chekhov, a seagull, a heroin dealer, among others, that slowly but surely forecast the tragic ending of the main character, brilliantly played by Queralt Casassayas. Both Garcia and Prat i Coll directed their own work, but I believe they could benefit from a director or dramaturg to streamline their plays, so they are more effectively resolved.

Àlex Rigola presented his take on Shakespeare’s Ophelia in Ofèlia (Panic Attack). In his adaptation, Ofèlia, drained and disheartened, appears in a dark forest, inside a car. She listens to a radio broadcast that informs the audience that in Denmark, Ofèlia, has disappeared and rescue teams are trying to find her. The short play revolves around Ofèlia (a compelling performance by Roser Vilajosana) dealing with a flat tire. During the ordeal, she plays Wagner’s Liebestod on the flute and climbs a tree. In the end, she cannot shake off her deep depression. Staged in an old warehouse, with a capacity of only 20 people, Ofèlia’s struggle, regardless of the cause that has brought her there, turns into a simple, yet effective, exercise about our failure, as a society, to grasp someone’s fall.

Hermafrodites a cavall o la rebel·lió del desig (Hermaphrodites on Horses or the Rebellion of Desire) premiered at the small Teatre Tantarantana. Written by Laura Vila Kremer, Raquel Loscos and Víctor Ramírez Tur under the direction and dramaturgy of Raquel Loscos and Víctor Ramírez Tur; Laura Vila Kremer’s monologue turned out to be one of the most interesting new works during the Festival. The play begins with a series of definitions of how a hermaphrodite has been described across cultures from Ovid, and Plato to the Rigveda and the Ardhanarishvara, to the Popol Vuh and the Gucumatz. During this exposition, Laura Vila Kremer stands in the back, changing positions, as if they were an exotic creature in a zoo, laying there simply to be scrutinized by our gaze. After that, Vila Kremer puts on a tuxedo and turns into a TV game show host where they ask the audience “What’s under the underwear?” But soon, all the jokes stop, and we are presented with Vila Kremer’s own intersex story, of a body belonging to both sexes and to neither exclusively. Her story is full of pain; mostly because her body is treated by the doctor and her mother as a secret, nature’s mistake, that she is forced to conceal, even from her immediate family. It is the issue that cannot be discussed, extremely confusing to a young person: “I was something, but they operated on me”, “the feeling that you have something broken inside of you”. Through social media, Vila Kremer asked intersex people to come forward and share their stories and, in a documentary style, she interviewed them. Projected on stage, all their stories are sadly similar: feeling strange in their own body, being told to keep it quiet, experiencing shame due to the behavior of the medical profession, being marginalized, and having to constantly explain who they are upon meeting someone, something that is even more challenging when it involves a romantic prospect. Those are the common threads of their moving stories. But, Vila Kremer, is adamant that their body is not a condition that needs to be repaired, it is perfect as it is and they will thrive. That is when she calls upon all the intersex people to get together as a “horde”, a group of rebels that stand up for themselves. The ending, with Vila Kremer shouting for her horde as if it were a warrior summoning her troops while riding a tall, imaginary horse, is extremely moving. A (documentary) play, like its subject, is impossible to define but thoroughly winning.

The biggest surprise of the Festival was, to me, Teatro La Plaza’s adaptation of Hamlet. The Shakespeare classic was directed and freely adapted by Chela De Ferrari to be performed by eight young actors with Down’s syndrome. The play starts with a film of a baby being born and it stops with the doctor, ominously, measuring its head. Then comes the ghost scene almost as written before the actors introduce themselves. They warn the audience that sometimes their speech freezes, they stutter, or they can forget their lines. They ask for patience because they always pull through. They also inform us that they will try to vocalize as well as they can, but supertitles will be provided so the audience can fully understand them. The role of Hamlet will be played aleatorily by members of the company. Jaime, Jaimlet, will play Hamlet at the beginning and he quickly informs us that it is as difficult to be Jaime as it is to be Hamlet. He explains that this is because some people, like Claudius, think that they can easily abuse them because they are nature’s mistake. All the details that in the original refer to being an outcast or a victim of life’s circumstances are translated in this version as having Down’s syndrome. It highlights the impossibility of them fitting in a society that rejects them. For example, Hamlet tells Ophelia “get thee to a nunnery” so as not to risk giving birth to kids like them. In another touching exchange, Polonius words to his daughter in the first act,

If it be so (as so ’tis put on me,

And that in way of caution), I must tell you

You do not understand yourself so clearly

As it behooves my daughter and your honor. (I,3)

are changed to introduce her medical condition. Polonio here warns Ofelia that she is not like the others because people have 46 chromosomes, but Ophelia was born with 47, because of the additional copy of chromosome number 21, a fact that resonates throughout the adaptation. This version of Hamlet also contains numerous witty scenes, such as Jaimlet calling Sir Ian Mckellen via Zoom to ask him seven questions about how to prepare for the role; or when Jaimlet rehearses the “To be or not to be” soliloquy in front of Lawrence Olivier 1948 film, trying to imitate him, before another actor interrupts him saying that he quits if he is forced to act like a statue. However, the emotion in this version of Hamlet is overwhelming at times. I doubt I will ever hear a more touching “words, words, words” declamation as voiced by an actor with a stutter or that death. Or as Hamlet himself says

So, oft it chances in particular men,

That for some vicious mole of nature in them,

As, in their birth–wherein they are not guilty,

Since nature cannot choose his origin— (I,4)

A double chromosome has changed these actors’ lives, and they know, as they express in their final lines, that death is never too far away and now may be the only time that they are allowed to dream.

Anton Pujol is an Associate Professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. He teaches Literature and Translation in both the undergraduate and the MA program in the Department of Languages and Culture Studies. He graduated from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and he later earned a Ph.D. at the University of Kansas in Spanish Literature. He also holds an MBA from the University of Chicago, with a focus on economics and international finance. He has recently published articles in Translation Review, Catalan Review, Studies in Hispanic Cinemas, Anales de la Literatura Española Contemporánea and Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies, among others. His translation of Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony (National Book Awards 2020 for Poetry) will be published by Raig Verd in 2022. Currently, he serves as dramaturg for the Mabou Mines company opera adaptation of Cunillé’s play Barcelona, mapa d’ombres directed and adapted by Mallory Catlett with a musical score by Mika Karlsson.

European Stages, vol. 17, no. 1 (Fall 2022)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Asya Gorovits, Assistant Managing Editor

Zhixuan Zhu, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- AVIGNON 76. A Festival of New Works by Philippa Wehle

- Almodóvar’s Women on the Verge in Portugal by Duncan Wheeler

- BRACK IMPERie. About “Hedda Gabler” by Vinge/Müller at Norske Teatret Oslo by Thomas Oberender

- Embodied Intimacy: The Immersive Performance of The Smile Off Your Face at Edinburgh by Julia Storch

- Fear, Love, and Despair – Radu Afrim: Director of Core Feelings by Alina Epîngeac

- Grec Festival de Barcelona, July 22 by Anton Pujol

- I Think of Curatorial Work in Scholarly Terms: An Interview with Ivan Medenica by Ognjen Obradović

- New Worlds Revealed in an Immigrant Journey, and an Unexpectedly Meaningful Universe Discovered and Destroyed Inside Styrofoam, at the Edinburgh Festival by Mark Dean

- Participation, Documentary and Adaptation: Barcelona Theatre May 2022 by Maria Delgado

- Report from Berlin, April 2022 by Marvin Carlson

- Report from Berlin (and Hamburg….) 5/2022 by Philip Wiles

- The Sibiu International Theatre Festival Transforms Dreams into Reality (The Magic of 2022 FITS in Short Superlative) by Ionica Pascanu

- Theatre in Denmark and The Faroe Islands – Spring 2022 by Steve Earnest

- The Polish Nation in a Never-Landing Aircraft by Katarzyna Biela

- The Piatra-Neamt Theatre Festival in Romania: 146 Kilometers from Heart to Heart by Cristina Modreanu

- Will’s Way at the Shakespeare International Festival Craiova 2022 by Alina Epîngeac

- Interview with the Turkish theatre critic Handan Salta on TheatreIST by Verity Healey

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2022 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2022