by Philippa Wehle

The Avignon Festival, July 7 to 26, 2022, director Olivier Py’s last festival after an eight-year leadership, introduced new voices and unknown works by artists from many different countries. Nine out of the forty-one official shows were by artists from the Middle East. Multiple languages were heard everywhere. Arabic, Persian, Greek, Chinese, Russian, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and English. There was Shakespeare in Italian and Richard II in French, but of special interest to me were the unfamiliar voices.

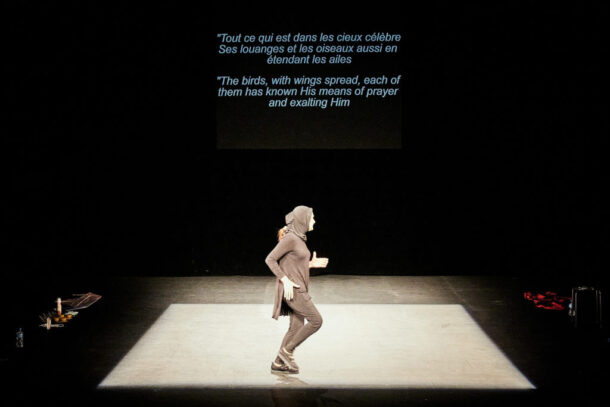

Jogging. Directed by Olivier Py. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage Festival d’Avignon

Jogging, by Hanane Hajj Ali from Beirut, a one-woman show by a fifty-something-year-old Lebanese theater artist, militant activist, playwright, and performer, in Arabic with English and French supertitles, was especially intriguing. I was curious to know what she would reveal to us about her life and her experience of jogging in the streets of her city, taking the same route every day, and how she copes with the difficulties of living in a city where electricity is scarce, bread is hard to come by and only the political and privileged live normal lives.

Billed as a “theatre in progress,” Jogging lived up to all of my expectations. Alone on a mostly empty stage, Hanane, a woman in black tights fit for a serious jogger, is gargling and performing warm-up exercises for her daily run. A few props – a coat, a plastic water bottle, and a stool – are all she needs to set the scene. She repeats the sound” Kh….” in a series of vocal exercises as the audience settles in.

After a good ten minutes, she invites an audience member to join her and introduce the play. She connects quickly with her audiences. Would they care to taste the fruit salad she has prepared? Or would one of them introduce Yvonne, one of the female characters that Hanane embodies in the play? Would another hold her feet as she does her push-ups?

Hanane finally introduces herself as “… the cool hijab woman married to the genius director who is the source of my headache and love!” “Men are known for lying,” she adds. “But luckily you are before a woman.” A Woman who is a mother with four children. A woman who jogs every day to avoid stress and prevent osteoporosis. She begins to run and walk in a circle around the stage as she continues her story. Enlarged images of Beirut’s ruined monuments accompany her. Beirut is “a city that demolishes to build and builds only to be destroyed.” As she jogs, birds are heard chirping, and pigeons are cooing as well as defecating on her.

As she runs and walks around the stage, she examines her life, a life “spent between mania and depression, fire and ash, adrenalin and dopamine.” She is an actress who dreams of great acting roles such as Medea, the character she has been obsessed with for a long time, a character who both attracts and repels her. She wonders who Medea is today in a torn city like Beirut.

Yvonne comes to mind. Yvonne, a true Lebanese citizen, decided to end the lives of her three daughters and then take her own. Hanane performs the letter Yvonne wrote to her husband before taking poison. It is in fact the note that Virginia Woolf left for her husband before she ended her life. She composes a song for Jason which she sings as she cuts out paper dolls in the shape of three little girls.

A great storyteller, like Scheherazade, she draws us in and holds our attention as she becomes the women in her stories. It is enough to don a raincoat or put on a blond wig or rub white cream on her face to inhabit them.

Later, she takes on the role of Zahra, a traditional young Lebanese woman who became a resistance fighter, dedicated to the cause, arrested and put into prison. Two of her children died in the 2006 war against Israel. Hanane performs her story without any sentimentality.

Finally, I will be Medea, the absolute woman, she claims. Finally, I will live. Medea, a woman who forces us to question ourselves and ask how far we would go to be able to respond to our suffering? This is the question Hanane leaves us to contemplate.

Le Septième Jour. Directed by Meng Jinghui. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage Festival d’Avignon

In contrast to the intimate moments spent with Hanane, Le Septième Jour (The Seventh Day), a world premiere, directed by Meng Jinghui from Pekin, fills the entire stage at the Cloître des Carmes. Adapted from Yu Hua’s 2013 novel of the same name, the staged version attempts to be a critique of contemporary Chinese society, but the message gets lost in the multilayers of stage activity. As we enter the theater, a group of skeletons stares out at us from the rear of the stage. A giant incinerator, a refrigerator, a dining room table, a sofa, a live band, an impressive dinosaur sculpture, posters of Marilyn Monroe and Che Guevara, and much more set the scene. Smoke frequently pours out onto the stage.

On Day One, Yan Fe, a forty-one-year-old man, bursts into a funeral home-cum crematorium. He died in an explosion and now he is late for his cremation. He’s been held up, it seems. “I’m late,” he apologizes as he enters. “It smells like something’s burning.” He is an ordinary man, suspended in time, with no tombstone, no urn, and no grave. Musicians and technicians accompany him through his seven-day journey which he seems to race through at a feverish pace.

Throughout the play, he moves among the souls of others whose cremation has been put off as well, living as it were on borrowed time in the afterworld. He meets up with the people who were important to him in his life. His adoptive father, his beautiful ex-wife who committed suicide, his neighbor, and a young woman called Mouse Girl who killed herself. He sees his birth mother from whom he was separated as a baby and ultimately reunites with his father.

On Day Two, he encounters his ex-wife, dressed in an alluringly bright red gown. At first, he is angry at her for leaving him. He shouts and tries to strangle her but they reconcile ultimately and recover their passion. On the other days, he is reunited with both his biological and adopted parents. At one point, Yan Fe finds himself within the story of Oedipus and the Sphinx and mysteriously refuses to play the role of Oedipus. Perhaps he does not need to solve the Sphinx’s riddle. On Day Seven, he finally finds his father, the man who adopted him when he found him as an abandoned baby on the train tracks. Their encounter is tender. Their bond is strong.

Later in the play, orange tennis balls mysteriously bounce onto the stage. Performers seem to enjoy throwing them at the audience who either keeps them or enthusiastically throws them back. In a final scene, large stone spheres roll across the stage, the incinerator makes grinding noises, and the cast gathers around a long table to share a meal of noodles and tell stories, leaving us wondering what the meaning of so much activity is.

MILK. Directed by Bashar Murkus. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage Festival d’Avignon

Strikingly different from le Septième Jour’s chaotic, loud, fast-paced, two-hour free-for-all, MILK, a work in progress by Bashar Murkus and the Khashabi theater from Palestine, opens in quiet silence, on an empty stage. Billed as a modern tragedy, MILK is a wordless, movement-based composition offering a series of striking tableaux of women who have suffered the loss of their sons.

Strange pinging sounds come from the dark, as lights come slowly up on a stage floor made of dark foam sponge-like rectangles. Five women enter holding life-size wooden dummies in their arms. These are the mothers of war. They rock the lifeless bodies of their sons, bouncing them faster and faster on their knees until they can no longer bear their weight and have to let them fall. They undo the tops of their dresses exposing large false breasts, engorged with the milk they no longer need. One of them carries her dummy to a chair and sits while the others stand behind her. Holding him on her lap, she picks up another and another until her lap is covered. For a moment, the other women stand behind her as if in a family portrait. These are strange and disturbing images.

Smoke fills the stage as a pregnant woman, carrying a bundle of flowers on her back, walks to an area where she seems to create a cemetery/garden. In contrast to the tragedy of the opening scenes, there is music and laughter. The women change into silk nightgowns and share the pleasure of eating oranges together. It begins to rain. The stage is inundated.

One of the women begins to pull up pieces of the floor, Carrying the wet slabs, placing one on top of the other, the women build a mound. Falling and slipping on the wet slabs, the pregnant woman makes her way to the top where she gives birth to the sound of dripping rain.

Her baby is not a wooden dummy but a full-grown man attached to her by a long umbilical cord. He tries to stand up and reaches out to his mother but he slips and falls. The five sisters reappear with bowls of water, they fling at him. Now the stage is covered with water. The other mothers silently sit in a row in the water. The newborn tries to sit in the laps of each mother, but they refuse him. They have embraced the wooden bodies of their dead sons, but they reject the living. They must continue to mourn.

Sans Tambour. Directed by Samuel Achache. Photo: Bouffes du Nord

Sans Tambour (Without Fanfare), collectively created by a team of nine young actor-musicians and singers, under the direction of Samuel Achache, is a wonderful musical show. Energetic and fun, with serious undertones, the two-hour piece offered a welcome respite from the many life and death dramas in the festival. Performed and sung to Robert Schumann’s Liederkreis Opus 39, Sans Tambour explores the theme of collapse, both personal and material. Buildings fall apart as characters struggle to recover from their own breakdowns.

The show opens on a two-story house in disrepair. A large tarp covers most of it. A carpenter, stage left, attempts to play a 45rpm recording of Robert Schumann’s Liederkreis Opus 39, on a record player but it is a failure. In frustration, he begins to knock down the walls of the kitchen. His “better half” joins him in a knock-down, drag-out shouting match. She sings of love and he responds with plumbing problems, accompanied by an ensemble of musicians and the voices of singers. On the second floor, things remain normal for a moment. A woman takes a shower, another brushes her teeth, and another reads a book. The show quickly moves on, however, as the entire house is reduced to rubble.

The show’s theme of unrequited love and the search for true love plays out in a series of short scenes. Perhaps the legend of Tristan and Isolde offers a model, but that story ends in tragedy.

The house is being destroyed, and their lives are crumbling as well but humor prevails in the form of a zany, mad romp complete with a piano falling from above on top of one of the musicians. He survives of course.

A young man wearing a bandage on his head has undergone brain surgery to cure his lovesickness. A doctor from the Institute for the Care of Broken Hearts tries to help. As the house crumbles into ruins and debris covers the stage, fragments of the house fly in the air, and plastic wine glasses are thrown around, but the debris is cleaned up and no harm is done. Perhaps love is but a romantic dream, but a necessary one.

Le Moine Noir. Kirill Serebrennikov. Photo: Nicolas Tucat

While rumors circulated that some audience members and critics were disappointed that memorable shows and major artists of past festivals were absent from this year’s program, Kirill Serebrennikov’s Le moine noir (The Black Monk) in the grand Honor Court theater (which seats at least 2000) was magnificent and memorable.

Serebrennikov’s free adaptation of an 1894 Chekhov short story was perfectly suited to the expansive Honor court stage, which is often an overwhelming challenge to theatre directors programmed in that venue. Le moine noir follows the story of Andrei Kovrine, a young scholar who is overworked and exhausted. He returns to his friend Pessotski’s country home to rest and recover. Pessotski, an old man, has devoted his life to his garden. He hopes that Andrei will marry his daughter Tania and tend to the garden once he is gone. Andrei and Tania agree.

Their story opens on a stage on which three large transparent wooden sheds, covered with cellophane plastic, lined up in a row, serve to house workers and other helpers on the estate. Temperatures have fallen and the crops must be sprayed. One of them, Pessotski, is looking forward to reuniting with his young friend. Andrei, however, is furious and treats his former mentor with anger and disdain. Tania worries that there is something very wrong with Andrei who is clearly not well. Nonetheless, the wedding festivities take place and are celebrated with dancing and drinking even though Andrei seems to be having a nervous breakdown. The large cast of performers playing the workers in the opening scenes, at first sitting or lying down on benches, help to capture Andrei and keep him from hurting himself.

The role of Andrei is played by three different actors, one speaks German, another English, and the third, Russian. Each one interprets the role somewhat differently, but all embody a young man who is losing his mind.

Divided into four parts, four variations on the same story, each one follows Andrei’s descent into madness. In Part 2, Tania is played by an older actress who fills us in on Andrei’s current state as the younger Tania admits that she has grown tired of Andrei’s agitation and constant philosophizing. She curses him in a letter as her father’s garden is given to strangers, after his death.

He is increasingly obsessed with a black monk he claims has informed him that he is a genius with a brilliant future. In Part 3 Andrei’s hallucinations have conjured multiple black monks who pursue him, close in on him, and seem to swallow him up. In Part 4, the sheds are knocked over and moved to the side of the stage to make room for an exhilarating dance sequence performed by monks twirling in circles like whirling dervishes. Serebrennikov’s extraordinary Black Monk ends with a projection of a giant poster STOP WAR, on the south wall of the Honor Court, a very personal statement by the director who is a well-known Russian dissident.

Philippa Wehle is a professor emerita of French, drama studies, and literature at Purchase College. She writes widely on contemporary theatre and performance and has translated numerous contemporary French language plays by Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute, Philippe Minyana, José Pliya, and others. Her current activities include translating contemporary New York theatre productions into French for supertitles. Professor Wehle is a Chevalier in the French Order of Arts and Letters.

European Stages, vol. 17, no. 1 (Fall 2022)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Asya Gorovits, Assistant Managing Editor

Zhixuan Zhu, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- AVIGNON 76. A Festival of New Works by Philippa Wehle

- Almodóvar’s Women on the Verge in Portugal by Duncan Wheeler

- BRACK IMPERie. About “Hedda Gabler” by Vinge/Müller at Norske Teatret Oslo by Thomas Oberender

- Embodied Intimacy: The Immersive Performance of The Smile Off Your Face at Edinburgh by Julia Storch

- Fear, Love, and Despair – Radu Afrim: Director of Core Feelings by Alina Epîngeac

- Grec Festival de Barcelona, July 22 by Anton Pujol

- I Think of Curatorial Work in Scholarly Terms: An Interview with Ivan Medenica by Ognjen Obradović

- New Worlds Revealed in an Immigrant Journey, and an Unexpectedly Meaningful Universe Discovered and Destroyed Inside Styrofoam, at the Edinburgh Festival by Mark Dean

- Participation, Documentary and Adaptation: Barcelona Theatre May 2022 by Maria Delgado

- Report from Berlin, April 2022 by Marvin Carlson

- Report from Berlin (and Hamburg….) 5/2022 by Philip Wiles

- The Sibiu International Theatre Festival Transforms Dreams into Reality (The Magic of 2022 FITS in Short Superlative) by Ionica Pascanu

- Theatre in Denmark and The Faroe Islands – Spring 2022 by Steve Earnest

- The Polish Nation in a Never-Landing Aircraft by Katarzyna Biela

- The Piatra-Neamt Theatre Festival in Romania: 146 Kilometers from Heart to Heart by Cristina Modreanu

- Will’s Way at the Shakespeare International Festival Craiova 2022 by Alina Epîngeac

- Interview with the Turkish theatre critic Handan Salta on TheatreIST by Verity Healey

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2022 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2022