The theme of the seventy-third Avignon festival was Odysseys, from classical references to contemporary interpretations, from Kevin Keiss and Maëlle Poésy’s free adaptation of Virgil’s Aeneid, focusing on Aeneas’ exile and wanderings, to Jean-Pierre Vincent’s five-hour Oresteia, performed in its entirety by his students from Strasbourg’s Ecole Supérieure d’Art Dramatique. Foreign and French authors and artists, some brought to the festival for the first time, spoke to the tragedies of migration, questions of identity and the nature of otherness in their festival offerings.

Nancy Huston’s Multiple-s, conception and choreography by Salia Sanou. Photo: Laurent Philippe.

Multiple-s – a polyphonic show by choreographer Salia Sanou from Ouagadougou, with captivating poetic texts read by their author, French-Canadian writer Nancy Huston, as well as a stunning solo by Germaine Acogny from Senegal and playful moments at the piano with musician David Babin, aka Babx, also from Burkina Faso – was especially successful in its exploration of alterity. On a simple white stage, with fluorescent bars of light on two movable structures, and a revolving circular platform, Sanou interacts with each of his invited guests in separate dialogues, exploring the nature of otherness and questions of identity through dance, the spoken word, and music and song. Through his exchanges with each artist, he asks himself: Who are you? What is it like to be uprooted? What is the nature of the Other? “We’ve all come from a starting point, and we have now become multiple selves,” he concludes. Multiple-s was definitely one of those enchanted evenings under starry Provencal skies of Avignon legend.

Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande, directed by Julie Duclos. Photo: courtesy Avignon Festival.

Even Julie Duclos’ Pelléas et Mélisande, a modern version of a tragedy written by Belgian symbolist author Maeterlinck in 1892, which at first seemed to be a faithful rendering of Maeterlinck’s tale of forbidden love, complete with castle, king and two princes, raised questions of migration and identity.

The show begins with filmed images of a young woman frantically running through a forest. Who is she? Where is she going? Where does she come from? Prince Golaud discovers her weeping next to a pond while he is hunting in the forest. He is drawn to this mysterious stranger and takes her back to his grandfather’s castle and marries her. Soon Pelléas, his half brother, returns home. True to Maeterlinck’s play, Mélisande and Pelléas fall in love. Golaud kills his brother in a fit of jealousy, and Mélisande dies as she gives birth to Pelléas’ child.

To tell this tragic tale, Duclos, her excellent cast, her team of musicians, and her sound, light, and video designers, created a magical set bathed in an atmosphere of foreboding and impending catastrophe. Barely any light filters through the dense forest. The King’s castle is a two-story house in the middle of a lawn made of crushed stone. The front wall of the house is open so that we can follow the intimate lives of this family on the verge of destruction. Inactive grottoes exhale a smell of death, we’re told that there are poor peasants hovering around the castle who are dying of hunger, and there is a threat of an uprising. Invisible forces beyond the control of the mortals seem to be in charge. A strong sense of the end of the world pervades.

Who is Mélisande? Is she a refugee fleeing from country and family unable to speak of the terrible things she has known on her journey? Does she represent today’s young people threatened by a world on the edge of disaster? Thirty-four year-old Matthieu Sampeur, who plays Pelléas, seems to think so. As he said in an interview: “Our generation is the first to experience the perspective of the end of the world as a reality that is actually foreseeable.” In Duclos’ Pelléas et Mélisande, this sense of doom is tangible.

Kevin Keiss’s Sous d’autres cieux, adapted from Virgil, directed by Maëlle Poésy. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

Meanwhile, Troy is burning, and Aeneas and his kinsmen must leave their home and begin an arduous journey in search of asylum. Sous d’autres cieux, Kevin Keiss’s contemporary translation of fragments of Virgil’s Aenead, directed by Maëlle Poésy and performed by members of her Crossroad company, follows their wanderings throughout the Mediterranean in search of a welcoming land. Their odyssey takes place on a mostly bare stage with a few tables that, when piled on top of each other, serve as their ship’s mast from which they can contemplate the sea around them.

The gods are ever present, unseen by Aeneas but seen by the audience through a glass wall. They are there to remind Aeneas of his duty to found a new city. They comment on and decide his destiny.

As Aeneas sets forth on his journey, carrying his father on his back and holding his small son, his followers execute a fascinating dance number. Moving forward with arms waving and feet swinging to the strong beat of drums, they gaze forward with the look of bewilderment and disbelief of a people that has been defeated. Led by Aeneas, they cross Libya, Greece, the coast of Epirus (1178th day), Etna (2,187th day), and many more places, constantly arriving, leaving, arriving and leaving again, encountering strange and different languages as they go forward. We hear of the ordeals they have to face, not only attacks by the Harpies but also the plague and fierce storms.

Finally Dido, Queen of Carthage, welcomes them and offers them a home. She falls in love with Aeneas, who shares her feelings. Their love story transforms the stage into a glorious moment of dance and music that celebrates their hopes of a future together, but the gods once more remind Aeneas that he must continue his extended wandering.

In the end, Aeneas and his people arrive at their destination, transformed by their odyssey. Keiss and Poésy have spoken of their Aeneid as not only a tale of migration but also a story about métissage. As the result of their many encounters with different cultures, Aeneas and his followers are no longer Trojans. Their identity has changed. They have become a mixed race.

Laurent Guadé’s Nous, l’Europe, Banquet des peuples,, directed by Roland Auzet. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

Nous, l’Europe, Banquet des peuples, by Laurent Gaudé, directed by Roland Auzet, is a “magnificent pamphlet against the European myth,” to quote critic Gilles Costaz, as well as a call for a new generation to strongly voice their concerns about the future of Europe. Is this theatre, people asked? There is no story line and there are no characters. Instead, there are numerous players from different countries, speaking a variety of languages, joined on the stage by a chorus of some sixty singers of all ages. Wearing their everyday clothes, they create a panorama of reds, yellows, blues, whites and greens that adds a colorful background to the banquet as they move about the stage.

As the show opens, ten rows of mattresses greet the audience. The mistral is blowing fiercely, and the mattresses are flying all over the stage. The audience laughs as stagehands race around trying to catch them. Where else but at the Avignon Festival can nature intervene to set the tone of a show? In this case, the element of surprise. The mattresses eventually serve performers when they climb and fall off the imposing white wall, which plays an important role in the show.

Standing in front of a large group of people, a young boy on one side of him, a young girl on the other, the well-known Québécois actor Emmanuel Schwartz leads this political and visual musical, two and one half hours of a whirlwind history lesson that covers key regrettable moments in history at breakneck speed: the Great Depression; revolutions including the May 1968 uprisings; colonialism; slavery; two World Wars; and so much more including concentration camps and the refugee camps at Sangatte, the Yellow Jackets and finally the European Union’s current crisis, accompanied by drums and guitars and glorious choral interventions. Individual witnesses speak their stories as the young people in the group climb up the wall, hanging off it, falling down and pushing it around to change the scene.

At each of the eight performances in Avignon, an important witness from the United States, Spain, Italy, Holland, France or Germany was invited to join the crowd on the stage and answer questions. These included former French president François Hollande among other distinguished guests. For my evening, it was Eneko Landaburu, a former official of the European Commission and distinguished member of the Board of Directors of Notre Europe–Jacques Delors Institute. Originally from the Basque country, he considers himself a European citizen. He first introduced himself and shared his views on avoiding wars and working to heal our democracies. As for the European Union, he addressed his regret that the current European Union is an exclusively economic union that has neglected culture.

For a grand finale, Schwartz leads the entire cast in a stirring rendition of the Beatles song “Hey Jude,” with emphasis on the words “Make it better.” The people – “warrior poets for an audience of poet-citizens” (Festival program) – have spoken.

Lao She’s Teahouse, adapted by Meng Jinghui. Photo: courtesy Avignon Festival.

Beijing’s Meng Jinghui’s adaptation of Lao She’s Teahouse, a much admired Chinese masterpiece written in 1956, was equally huge and equally prolific, but it lacked coherence. Chinese artists were featured at this year’s festival in three different shows. It was important that this was the first time they were invited to the festival in seventeen years, and Teahouse was a much-awaited event. Jinghui’s unrestrained three hours, played out against a staggeringly huge metal four-ton wheel and other set pieces of scaffolding that seemed unnecessarily overwhelming, was disappointing. There were many confusing stories to try to sort out, at least confusing to those of us who had trouble following the many references that were presented to us at a dizzying pace.

The play begins as a group of men seated on the scaffolding yell, “We are all in the same boat!” at the top of their lungs, for fifteen minutes. This seemed unnecessary, but hopefully the next scene of a large group of people from many different social backgrounds gathered at the Wag Lifa’s teahouse to talk about their lives and families and sip tea would enlighten us as to the through-line of this epic piece. Bits and pieces did come through, about three periods of Chinese history during the first half of the twentieth century, as experienced by three generations of the teahouse owner’s family.

When all is said and done, Teahouse depicts a world of turmoil and confusion, which seems appropriate given the overall subject. Every trick in the book of theatrics is used to hold our attention. The actors throw buckets of fake blood at each other, they threaten to shoot each other or themselves, strobe lighting prevails, and tribute is paid to Western avant-garde companies such as the Living Theatre along with references to Coca-Cola, the Internet, Michael Jackson, Brecht, and others. One player seems to complain that he can’t leave as long as the audience is still here. As one can imagine, this was met with laughter.

In the end, the wheel slowly begins to turn, and one of the performers jumps on board, seemingly to throw papers and piles of books and other detritus of civilization off the wheel. It was fascinating to watch him jump from one spoke to the next. taking real chances with his life, yet surviving….

Wen Hui’s Ordinary People, directed by Jana Svobodova. Photo: courtesy Avignon Festival.

In contrast, Ordinary People, by well-known Chinese choreographer Wen Hui from Beijing and Jana Svobodová, a noted theatre director from Prague, was a much more accessible example of new work from abroad. Nine artists, four Chinese and five from Czechoslovakia, born between 1942 and 1988, have accepted the challenging project of sharing their personal experiences of growing up under communist regimes in just one and one-half hours. Wen Luyuan, a guitarist, Jan Burian, a musician, Pan Xiaonan, choreographer and dancer, and Vladimir Tuma, a retired metal worker who is also an artist, tell their stories in their native languages. Each one has written a text which they express through dance, music and performance.

On a set composed of a metal barricade for crowd control, cardboard boxes of different sizes, musical instruments, and a very large screen in the back, they keep us entertained with a lively rock concert and various comedic numbers which actually prove to be quite serious. As the show begins, we are treated to a very loud rock concert played to the hilt by a smiling guitarist. A man stands up in a box. Another pushes him down, but he pops up again and again like a puppet who will not stay down. Vladimir Tuma stands in front of a tall column telling his story of growing up in Prague under the communists. He is constantly interrupted by a loud noise so that we do not get the whole picture. A woman climbs an imaginary ladder, falls down, and gets up again. These are just samples of the artists’ determination to survive.

There is much moving of the barricade, the boxes, trunks and the platform to make room for the performers to extend their stories. In one especially memorable moment, a young Chinese dancer tells her horrific tale of a childhood of abuse as she twists her supple body through the bars of the barricade in a fascinating solo that exemplified how these “ordinary people” have refused to be victims of their repressive societies. Clearly these “ordinary people” are anything but ordinary.

Alexandra Badea’s Points de non-retour (Quais de Seine). Photo: courtesy Avignon Festival.

In an entirely different vein, Points de non-retour (Quais de Seine), by Romanian-born Alexandra Badea, who is now a naturalized French citizen, is the second play in her trilogy entitled Points de non-retour. Quais de Seine is an intimate text-based play. There are just four characters: Nora, a documentary film maker; a nameless therapist; Younes, a young Algerian Arab man living in Paris; and Irene, his girlfriend, who comes from a French Algerian family, formerly settled in Algeria but forced to leave after the Algerian war. We first meet Nora lying on a hospital bed stage front. She is asleep while a therapist asks her questions which she does not answer. On a stage within a stage, we watch a young couple making love.

The play moves back and forth between the hospital and the room where Irene and Younes are living. As Nora slowly unravels the mystery of her reasons for being in the hospital, the young couple realizes that they cannot be together for personal and political reasons. Younes wants to return to his native Algeria, and Irene, who is pregnant, insists on raising their child in France with her French Algerian family, who do not know that the child’s father is an Arab. They are caught in a Catch-22 situation. We follow these characters as their lives evolve and secrets are revealed.

All three of the plays of Badea‘s trilogy concern her quest to uncover memories that have been officially covered up by History, real stories of “people buried in the archives of history.” The stories that nobody wants to hear are the subjects of Nora’s broadcasts. With the help of the nameless therapist, Nora slowly remembers bits and pieces of her past, most particularly a plaque on the St. Michel bridge dedicated to the memory of the many Algerians who were victims of a bloody massacre by the French police when they were holding a peaceful demonstration on October 17, 1961. This becomes the key to her search for the truth.

Kirill Serebrennikov’s Outside. Photo: courtesy of Avignon Festival.

Outside by Kirill Serebrennikov, Russian filmmaker and theatre director of the Gogol Centre in Moscow, was a much anticipated event at the festival. Needless to say, Serebrennikov, who was under house arrest from August 2017 to April 2019 for supposedly embezzling state funds, and now faces a ten-year jail sentence, was not present in Avignon. He is not allowed to travel outside of Moscow, but he managed to create a magnificent play from a distance. Rehearsals took place at his center in Moscow, and daily follow-ups via USB keys allowed this world premiere to take place.

Outside was inspired by the work of the young Chinese photographer and poet Ren Hang, who committed suicide at the age of thirty in 2017. The two dissidents had planned to meet to work on Serebrennikov’s play. Instead, Outside became a powerful tribute to Hang’s life and art.

A large cityscape partially covers the back stage wall.

Before the show begins, stagehands climb up ropes to add new images to complete the urban scene. Outside, the city is growing before our eyes. Inside, a man named the Escapee inhabits a claustrophobic room with a single window, placed on a wooden platform that is moved to make room for what little action there is as the play opens.

A loud knocking at the door interrupts the Escapee’s reverie. Men from the Russian Federal Security Service have come to interrogate him. They search him, turning him upside down as if to shake some secret out of him. This very unpleasant visit has become a regular occurrence in his life in which there is no contact with other people.

As if to prevent him from giving into despair, Ren Hang, played by Yang Ge, enters the room conjured by the Escapee. They quietly smoke a cigarette and look out the window. Thus begins a powerful play that recreates Hang’s special world, “a painful, depressive place, but at the same time incredibly charming and… bright and naïve. That invites us to reflect on ourselves,” to quote Serebrennikov.

A third character, a ballet dancer from the Bolshoi Ballet seems to provide a contrast to the choices made by the two dissidents to remain free to practice their art despite the state in which they live. He has collaborated with the Russian regime in his decision to enlarge his behind and thighs in order to join the national theatre. “They told me to grow a big ass, “ he tells the Escapee and Ren. “My ass grew and grew. And now I am the premiere dancer.”

Through dance, music, startling and beautiful images, and quotes from Hang’s poetry, the play proceeds as a series of fantasies that introduce us to the world of uninhibited sex, in a scene of an imaginary meeting between Ren Hang and Robert Mapplethorpe at a famous night club in Berlin, where black-leathered bodies enjoy explicit S & M movements, to a recreation of Hang’s photographs of naked bodies, performed by the members of the Gogol Center in a series of fascinating and beautiful poses of their naked bodies holding bouquets of exotic flowers and plants in endless combinations.

In Outside, everything that is happening on the stage is inspired by Ren Hang’s visual images and his poems. Serebrennikov’s strong connection with Hang’s thematic material – identity, sexuality and the individual’s place in society – is paramount to an understanding of his theatre. His is not a political social theatre, as it might appear to be. It is a theatre searching to find love and beauty in a hostile world.

“I do not create political social theatre,” he told an interviewer, “[Mine is] a theatre of powerful connections, a theatre based on human, emotional, and intellectual relationships”

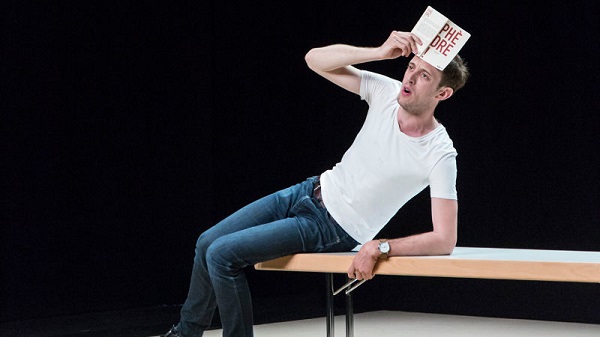

Jean Racine’s Phèdre!, adapted by François Grémaud. Photo: courtesy of Avignon Festival.

Phèdre! by Swiss author François Grémaud, read and performed by Romain Daroles, provided audiences with a delightful evening of pure joy. Daroles’ comedic retelling of Jean Racine’s seventeenth-century classic tragedy about the Queen of Athens’ illicit passion for her step-son, had the audience laughing non-stop for one and one half hours. To top it all, Daroles handed the audience copies of Grémaud’s text, published by the VIDY Theater in Lausanne.

Rumors had it that the 2019 festival was somewhat underwhelming and disappointing. My experience of this year’s festival was very different. For me, I found a theater of exhilarating moments and powerful connections, lived through words, music and dance, a “horizontal theatre” rather than a “vertical one” to quote Kirill Serebrennekov, “a theatre based on human, emotional and intellectual relationships.”

Philippa Wehle is Professor Emerita of French Language and Culture and Drama Studies at Purchase College, State University of New York. She writes widely on contemporary theatre and performance and is the author of Le Théâtre populaire selon Jean Vilar, Drama Contemporary: France and Act French: Contemporary Plays from France. She is a well-known translator of contemporary plays with a specialty in creating supertitles in French for emerging theatre companies. Dr. Wehle is a Chevalier in the Order of Arts and Letters.

European Stages, vol. 14, no. 1 (Fall 2019)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Stephen Cedars, Assistant Managing Editor

Dohyun Gracia Shin, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 73rd Avignon Festival, July 4-23, 2019 : Odysseys, past, present and future by Philippa Wehle.

- Ibsen in London by Marvin Carlson.

- Report from London (November – December, 2018) by Dan Venning.

- It’s All in the Wrist: How Nina Conti Faces Off with Reality by Katy Houska.

- Staging Trauma: A Review of Bryony Kimmings’s I’m a Phoenix, Bitch by Rachel Anderson-Rabern.

- Difficult Pasts and Revivals: Madrid Theatre Summer 2019 by Maria M. Delgado.

- Cultural Diversity in the Kunstenfestivaldesarts (Brussels) 2019 by Manuel García Martínez.

- Tampere Theatre Festival: Progressing Society by Pirkko Koski.

- Nasza Klasa in Georgia by Mikheil Nishnianidze.

- Young and Critical Voices of Turkey I: “Theatre helps us to hear each other.” A Conversation with Irem Aydın by Eylem Ejder.

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019