This is one behemoth of an evening, and no theatre in the US would have begun a five-and-a-half-hour night at 7pm, or dared to limit it to one intermission. Castorf has a reputation for testing the limits—of his actors, the material, and the viewers. Being well into retirement age, he is still going strong and has much to contribute. I am glad I didn´t check on the running time before I went to the theatre, for I may have forgone seeing this exceptional production.

The title of Dürrenmatt’s novel Justiz would seem to translate easily into English as Justice; but this in fact would be inaccurate. “Justiz” in German is not justice, but rather “the judiciary” or “judiciary process.” The difference between justice and the judicial system is one of the main themes in a novel that has an abundance of them. Justiz touches upon the unknowability of truth, the vagaries of perception, and (a very Dürrenmattian topic) the stark contrast between how his home country of Switzerland sees itself—neutral, humanitarian, pastoral—and how it comports itself in the world. Swiss neutrality, in his view, is not so much a mediating influence as a license to do business with everyone and everything while remaining on the sidelines when there are real problems to solve. Dürrenmatt was one of the first artists to speak out about what he conceived as Swiss cynicism: an army whose main strategy in World War II was to protect itself, and that has become practically useless since; a banking system that allows money to be raked in from all sides, making its citizens incredibly wealthy but shuttering itself from the outside world. While Jews who didn’t have money had an ‘R’ stamped into their passports (“Refoulé,” rejected) and were turned back to certain death, Nazi loot—money, gold, and art—landed in Swiss bank vaults. Only way too many years later did the Swiss banks grudgingly return some of it to the estates of its rightful owners. And today? Not much better. While Swiss companies do good business with the EU and the world at large, they are very resistant to making any accommodations for the immigrant workforce—be it from EU countries or, God forbid, seeking refuge from other parts of the world. And Dürrenmatt had his countrymen’s number. Back in the seventies he composed a “Swiss Psalm,” titled like the national anthem, which includes such pithy lines as these (my translation): “Once I thirsted for your faith, my country, now I thirst for your justice / Truly / The asses of your prosecutors and judges weigh so heavily on it / That I can hardly stand the word freedom you keep bandying about / To prove your credibility / In which nobody believes anymore / Only your banking secrets are believable, / What have you become, my country?”

Dürrenmatt began working on Justiz in 1957, and it was supposed to be completed in three months. But after writing parts I and II, both set in 1957, he couldn´t find the right ending. In 1985 the Zurich publishing house Diogenes asked him whether he wanted to publish the work as a fragment. In response Dürrenmatt reluctantly picked it up again, could hardly remember what he had intended almost three decades earlier, and added a part III, set in 1985, as a postlude. Justiz is a philosophical novel, expansive, dark, and funny, pretending to be a mystery. It would be his last completed novel and Dürrenmatt died in 1990 at the age of 69. A film version of Justiz, starring Maximilian Schell, was released in 1993.

Frank Castorf, longtime artistic director of the renowned Volksbühne in Berlin and theatrical legend of the nineties and early aughts, had, before Justiz, never worked with a text by Dürrenmatt. However, the material seems eminently suited to Castorf’s anarchic fervor and talent for creating collages and amalgamations of wide-ranging themes. But unlike his previous work at the Schauspielhaus Zürich, Dostoyevsky’s The Unknown Woman and the Man under the Bed in 2017, Castorf’s Justiz was constrained by the publisher’s insistence that he stick to material by Dürrenmatt and Dürrenmatt alone. Although the novel is vast and sprawling enough to suit Castorf´s taste, he did add and integrate some other essays by Dürrenmatt into the evening.

Kohler (Robert Hunger-Bühler) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

The plot of the novel Justiz seems simple enough, following known Dürrenmattian lines of mysteries that remain tragically unsolved (as in his 1958 Das Versprechen, adapted for film as The Pledge with Jack Nicholson). The high-ranking Zurich politician and businessman Dr. h.c. Isaak Kohler (Robert Hunger-Bühler) nonchalantly steps into a well-known restaurant—here called Du Théâtre but referencing a famous restaurant in Zurich—and shoots the literature professor Dr. Winter (Ueli Jäggi, in one of his multiple roles). He calmly lets himself be arrested, is convicted, and goes to prison, where he proves himself to be a very happy inmate. While in prison he hires the young lawyer Spät (Alexander Scheer) to investigate the case under the assumption that Kohler is not the murderer. He claims this to be a purely intellectual exercise, since “Reality is merely a special case of all possibilities, and therefore could be thought differently.”

Prostitutes (Teresa Matusadila, Manuela Hollenweger), a man (Ueli Jäggi), and Spät (Alexander Scheer) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

Spät immediately smells a rat, but he needs money, and although he is convinced of Kohler´s guilt, he takes on the case, hoping to succeed with his integrity intact. What he finds sends him into a downward spiral, into the depths of the city, its underbelly of corruption and lurid sexuality. Since the case was handled without great care, Kohler is indeed retried and is acquitted. But Spät´s mission is not over. He keeps digging deeper and deeper, past all reason. He ends up an alcoholic, a lawyer only to his whores and bitterly furious at having spent his life as a pawn to Kohler, the man he hates with all his guts but won´t ever bring to justice.

Castorf´s theatrical adaptation, a great deal more than the novel, revels in the world of shady deals, hidden motives, and lots and lots of drinking, smoking, yelling, as well as many sad but ferocious sexual interactions and trashings. The novel is told in retrospect, as a testimony, before Spät commits suicide, which he suspects Kohler to have anticipated. “Do you play billiards?” Kohler asks him at their first meeting, long before anything has happened. Spät says no, and Kohler remarks, “A mistake.”

Spät (Alexander Scheer) and Lucky (Jan Bülow) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

He chooses Spät precisely for his lack of knowledge of a game in which Kohler excels, and which determined his strategy: playing “à la bande,” a system of indirectly landing the target ball in the pocket. Because of course he’d had a motive—revenge for the rape of his daughter, Hélène (Irina Kastrinidis), by a group of people who all end up dead, though only one of them by his own hand. Once the story has moved into the eighties—with Kohler now almost a hundred years old and pushed in a wheelchair by that daughter—his story of the murder becomes a tale, told to the great amusement of a party crowd at the Schauspielhaus, his stoic daughter at his side. “He could have told them he’d been the director of a concentration camp, they wouldn’t have batted an eye.”

The main actors are long-standing collaborators with Castorf, used to his working method of not rehearsing per se, but experimenting, thinking, playing with and trying out ideas right up to the opening, relying on the cast to pull it all together on the night. Without such an experienced team as Hunger-Bühler, Scheer, Jäggi (also a Christoph Marthaler veteran), and Kastrinidis, this method might very well have backfired.

Although there is dialogue between characters, most of the text remains narration or commentary. The story of the beating and killing of Daphne Müller (Julia Kreusch), the beautiful, sensual, and licentious impersonator of Monika Steiermann—leading the expansive lifestyle the real Monika Steiermann, a dwarf, cannot—is presented behind glass while narrated in front of it. This theatrical device creates an intentional distance to the characters—in the Brechtian tradition—whereas Dürrenmatt´s novel allows the reader to feel “close” to the narrator of parts I and II, the lawyer Spät. This means that in the theatre you find yourself emotionally stirred via your intellect, the language, the images Castorf creates with his protagonists, but rarely by the characters themselves. Such an approach is more in the Germanic tradition of theatre than the Anglo-American.

There are numerous monologues, excerpted from Dürrenmatt´s novel: on the history of Switzerland, the barbarism of classical music—Beethoven´s Ninth Symphony goes well with pot-au-feu, the prudish gayness of the city of Zurich, national differences between Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Germany, and France, culminating in “the world will either perish or turn into Switzerland.” I personally enjoyed each and every one of them, as Dürrenmatt´s precise poetry and dry humor came wonderfully into relief. And Castorf didn´t impose himself onto Dürrenmatt´s material; rather, the expansive material and writer finally found a theatrical mind equally generous in scope.

Spät (Alexander Scheer), Hélène (Irina Kastrinidis), Lucky (Jan Bülow), prostitute (Teresa Matusadila) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

The cast throws itself with exuberance and great expenditure of energy into the urgent turmoil, with nine-year-old Mikis Kastrinidis, son of Irina Kastrinidis and Castorf, as the demon dwarf Monika Steiermann, tossed into the mix. His calm, threatening presence is in stark contrast to the hyperactive despairing adults around him. It is Monika Steiermann who has ordered and enjoyed the rape of Hélène by Dr. Winter, Dr. Benno (Nicola Rosat, who also plays other roles), and Daphne Müller.

Monika Steiermann (Mikis Kastrinidis) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

Castorf creates some immensely powerful imagery. Daphne Müller aka Monika Steiermann, dusty white, covered in cocaine, poses as a statue confounding the lusting Spät. She stands immobile at a window, looking down on a man out front telling her story. Or we see her, still chalky, in functional underwear with a wig, sewing something on her fur coat: a Penelope image, intimate, tranquil, right before she gets beaten up. While the use of cameras and a screen mostly drives home the point that we never see things directly, it also makes way for some impressive directorial choices. Ueli Jäggi (in the novel it is the narrative voice of the author) recounts the story of Hélène´s rape as he stands in profile, giving an interview to the camera, while on the screen we see only his mouth. Hélène finally shouts her pain, sitting on the dissolute Spät´s lap, eyes in anguish, her face also in close-up. Daphne Müller also gets to tell her own story of being attacked, but her speech becomes more and more garbled and incomprehensible, as the described beating progresses, and her mouth gets punched. We see no blows, we see their consequences in her speech. These are all masterful choices of camera usage, directing the focal point to greater power.

Daphne Müller (Julia Kreusch) and man (Ueli Jäggi) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

Overall, the narrative voice is mostly male. Every once-in-a-while two ladies of the night, played by Manuela Hollenweger and Teresa Matusadila, deliver commentary in Swiss dialect or French, respectively. But though the men all have levels of complexity—they are in turn stentorian, desperate, sad and yet funny—the women stay more monochrome, passive, victimized, either half-dressed or clad in porn outfits. And yes, there is sexy dance choreography. This may be perfectly adequate for the prostitutes and Jan Bülow as the pimp Lucky, but also Daphne Müller, despite her representing a glamorous sexuality, is hardly ever dressed. Hélène is first seen in a pink tulle negligée in her first real appearance, then mostly in various low-cut gowns.

Hélène (Irina Kastrinidis) and Spät (Alexander Scheer) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

The men are allowed more variety. Their clothing ranges from suits and coats to beautiful transvestite outfits to fat suits, running the gamut from serious to silly. But of course that is not just Castorf, though he definitely has a macho track record; it is true to Dürrenmatt´s view of women as well. The novel has two male narrators—Spät and the writer, “Dürrenmatt”—and Hélène remains under her father´s dominion to the end, pushing the hundred-year-old’s wheelchair when he appears at the theatre.

Man (Ueli Jäggi) and Kohler (Robert Hunger-Bühler) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

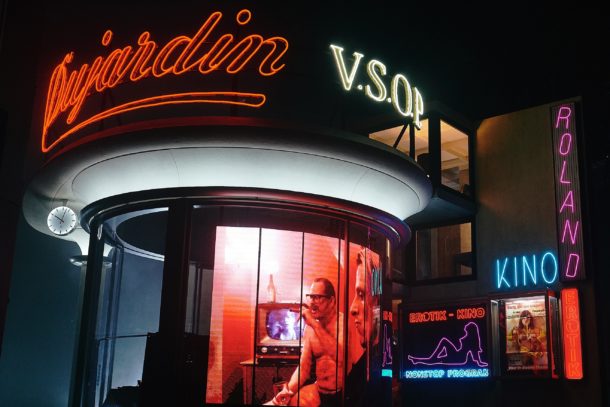

The evening of Justiz is a maelstrom of worlds, thoughts, and ideas, with one theme overriding all others: the fundamental unknowability of the world, people, reality, and ultimately something like absolute truth. This is presented verbally but primarily demonstrated in the visual and the action. Aleksandar Denić’s set is a tight little rotating number situated in the middle of the large stage of the Schauspielhaus. It combines almost cubistically the Café Bellevue, the restaurant Kronenhalle, which is topped by the famous “Rondell,” to which is added the Le Corbusier House. Between the Le Corbusier and Café Bellevue there is a red passageway leading to another building facade: that of the last and now legendary sex movie house, Kino Roland.

Stüssi-Leupin (Nicolas Rosat) and Spät (Alexander Scheer) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

At no time can the set be seen in its entirety, and the action doesn’t necessarily occur within what’s in view at any given time. The actors are constantly followed by two cameramen, and we often follow the characters onscreen. This makes for tiring viewing, as it frustrates the desire for an unobstructed view and thwarts at every turn one´s increasingly ferocious need to decide for oneself what one wants to see. But this frustration is intentional. Castorf wants us to notice how selective our perception is, how little we really control in what we see or then understand. The multiple filters of our viewing—I see only a third of the set and hardly anything of the actors, while there’s a close-up of what’s happening on the screen—is in a way a contemporary adaptation of Plato’s Cave. We never see what really is there, and we certainly never can understand what is really happening, so the best we can do is realize this limitation and allow for a humbling. Dürrenmatt was a master in layering realities, and Castorf is no slouch either. The audience on the night I was there had a mixed tolerance for frustration. The largest number of people left during the first half (it being two and a half hours until the first and only intermission), made to watch onscreen an overlong orgy with Spät and pretty much everybody else, except for Kohler, with lots of incoherent yelling, drinking, vomiting, and sucking on faces or other body parts.

Prostitute (Teresa Matusadila), Spät (Alexander Scheer), prostitute (Manuela Hollenweger), Lucky (Jan Bülow), Stüssi-Leupin (Nicolas Rosat), Hélène (Irina Kastrinidis) of Justiz, by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Matthias Horn.

It is hard to assume that Castorf didn´t do it on purpose: Let´s weed out the good people, and see who´s in for the ride. Indeed, another sizable chunk of the audience left during intermission (much more polite—don´t make a statement, just disappear—very Swiss), so the remaining two-thirds of the viewers moved to the better seats in the middle, grinned at each other, and relished the second half in a community of diehards. The actors onstage seemed relieved: finally they were playing for people who actually wanted to be there, and the evening took off.

Lawyer Spät is a mess, he may never really knows what happened, it is up to Ueli Jäggi “Dürrenmatt” to resolve the plot, but it remains unclear whether Kohler´s revealed motive is the true one. Did he avenge his daughter´s rape, or did he use that as a pretext to kill off business associates? Or is there a completely different motive behind it all? Spät will definitely never know, Hélène has her suspicions, and Kohler won´t tell.

Kohler’s last words, fifteen minutes of text, are delivered downstage center in the dark, and despite much verbiage, the character never is revealed. He leaves, and Ueli Jäggi takes over delivering a final closing monologue—speaking in Dürrenmatt´s well-known Helvetic lilt, summing it all up—with a sliver of light on his face.

“Didn´t Spät have the freedom to turn down the assignment to find a murderer who didn´t exist? Didn´t he have to find a murderer who didn´t exist just as man, having eaten the fruit from the tree of knowledge, have to find a God that didn´t exist, the devil? Is the devil not a fiction of God to justify his wayward creation? Who is guilty? The one who gives the assignment or the one who takes it? The one who forbids or the one who disregards the forbidden? The one who makes the laws or the one who breaks them? The one who gives us freedom or the one who acts freely? We perish through the freedom that we allow and that we allow ourselves.”

Katrin Hilbe is a director of opera and theatre working both in the US and in Europe. Her production of Julia Pascal’s St Joan won the award for “Best Direction and Adaptation” at the Dublin International Gay Theatre Festival, and her staging of Richard Strauss’s Salome for New Orleans Opera was awarded “Best Opera Production.” Select credits include Shooter (New York, Liechtenstein, Konstanz, Rome), Fägfüür (Liechtenstein, Zürich, Dornbirn), Fremd bin ich Eingezogen … (Konstanz), Die Schumann Sonate (Liechtenstein, Basel, Zürich), In Bed with Roy Cohn (New York), Breaking the Silence (Edinburgh), and Falstaff (Frankfurt). During 2007–2010 Katrin was the primary Assistant Director for Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen under the direction of Tankred Dorst at the Bayreuth Festival.

European Stages, vol. 13, no. 1 (Spring 2019)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Introductory Note by Kalina Stefanova.

- “Andrzej Tadeusz Wirth (1927 – 2019) – White on White” by Krystyna Illakowicz.

- Lithuanian Marriage in Warsaw or The Last Production of the Great Eimuntas Nekrošius by Artur Duda.

- “My, Żydzi polscy [We, Polish Jews]”: A Review of Notes from Exile by Dominika Laster.

- A Report on the State of Our Society, According to Jiří Havelk in The Fellowship of Owners at VOSTO5, Prague, and Elites, at the Slovak National Theater, Bratislava by Jitka Šotkovská.

- About Life as Something We Borrow. On the Stages of Pilsen (In the 26 th edition of the International Theatre Festival There) by Kalina Stefanova.

- Redesigning Multiculturalism or Japanese Encounters in Sibiu, Romani, The Scarlet Princess, written and directed by Silviu Purcărete, inspired by Tsuruya Namboku IV’s Sakura Hime Azuma Bunshô by Ion M. Tomuș.

- About Globalization: A “Venice Merchant” on Wall Street, at the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj in Romania by Maria Zărnescu.

- The Patriots, Mary Stuart and Ivanov and the Rise of the Drama Ensemble of the National Theatre in Belgrade by Ksenija Radulović.

- The Unseen Theatre Company or How to See Beyond the Visible: The Shadow of My Soul and the Theatre of Velimir Velev by Gergana Traykova.

- Multilingual Pirandello, Understandable to Everyone: The Mountain Giants at the Croatian National Theatre “Ivan pl. Zajc”, Rijeka by Kim Cuculić.

- The return of the repressed: the ghosts of the past haunt Barcelona’s stages by Maria M. Delgado.

- A poetics of memory on the Madrid stage (2018) by Maria M. Delgado.

- The Danish National Theatre System and the Danish National School of Performing Arts: December in Copenhagen 2018 by Steve Earnest.

- Towards a Theatre of Monodrama in Turkey 1 by Eylem Ejder.

- Where Is Truth? Justiz by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at the Schauspielhaus Zürich by Katrin Hilbe.

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson.

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019