In November 2018, when we received the sad information about the Lithuanian director Eimuntas Nekrošius’ unexpected passing in Vilnius, it turned out that his production of Witold Gombrowicz’s Marriage at the National Theatre in Warsaw (premiere: June, 15th, 2018), was his very last work.

Nekrošius embarked on his European career in Poland. Since the early 1990s, he had presented his greatest productions as part of the International Theatre Festival “Kontakt” in Toruń, where he used to be invited—first by Krystyna Meissner and, later, by Jadwiga Oleradzka. There were a total of ten Nekrošius productions there, including Alexander Pushkin’s Little Tragedies, Chekhov’s Three Sisters, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and last but not least, Goethe’s Faust. All of them were world literary classics, interpreted in a distinctly unique way by the master—or I would even say—author of the theatre of sensual metaphors.

Having won numerous awards during the “Kontakt” festival, Nekrošius set out to conquer Europe. He worked particularly often in Italy, although the idea of him working again in Poland appeared immediately after the monthly magazine Theatre gave the director the prestigious Konrad Swinarski Award in 1997. He was the only foreigner whose artistry was that highly appreciated. The director received this award again in 2017, after he had staged, during the previous season, The Forefathers’ Eve, by Adam Mickiewicz, one of the essential pieces for Polish culture, at the National Theatre in Warsaw for the 250th season from the founding of the first Polish stage (premiere: March, 10th, 2016). Gombrowicz’s Marriage, which was put on two years later, was not supposed to be the last stage of his cooperation with this theatre.

Nowadays hundreds of theatre festivals, many of which are international, take place in Poland. In the early 1990s, when the Berlin Wall was falling, the Soviet Union collapsing and the new Poland was starting, there were only a few such events. “Kontakt” in Toruń was going through its culture-forming stage. Over twenty performances entered the competition for its first seasons. Lithuanian theatre was hardly known in Poland, productions from Eastern Europe (more Eastern than Poland itself) were labelled as “Soviet” or “post-Soviet” theatre. Compared to many artists from the former USSR, Nekrošius – a graduate of the Russian Institute of Theatre Arts (GITIS) – was strikingly dissimilar. He was turning classic dramas into fairylands, full of weird creatures – squeaking, searching for the unknown, continually striving for something. He developed individual stage hieroglyphs: a series of mysterious signs, created by actors, who set the matter—the objects as well as their bodies—into motion. Intuitive viewers were able to discover deep metaphorical meaning hidden within this artistic vision, which proved how thoroughly the director read the text to visualise/materialise its metaphors.

As Forefathers’ Eve belongs to the canon of Polish sacred texts with a rich tradition of staging in the 20th and 21st centuries, the decision to have Nekrošius put it on was an act of courage, both on the part of the artist and of the National Theatre’s leaders in inviting him. The Lithuanian director did the production with characteristic flippancy; he came up with his artistic interpretation of the romantic drama, underlining his ironical and critical attitude. One of the Polish critics Jacek Wakar said:

“In his brilliant staging of Forefathers’ Eve, Eimuntas Nekrošius breaks with tradition and avoids long-established typically Polish way of interpreting this great drama, looking for hidden meanings of words. He gives the performance a hint of irony, lets laughter resound, multiplies puzzles and questions. […] The National Theatre in Warsaw has a new performance perfectly corresponding with its mission. Who else but the national stage is supposed to redefine the classics, show it in a different (even Lithuanian) light?”

Nekrošius retained the same approach when staging Marriage by Witold Gombrowicz, which is regarded as one of the founding texts for contemporary Polish theatre. Gombrowicz, who had lived abroad as an emigre since the outbreak of WWII, was not—to put it mildly—the favourite of the Polish People’s Republic authorities. However, it was he, together with Tadeusz Różewicz, Sławomir Mrożek and Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (the precursor of the theatre of the absurd), who made a major contribution to the development of modern Polish theatre. Marriage owes its reputation as a masterpiece particularly to Jerzy Jarocki, who staged it many times. Marriage is a poetic treatise on creating the world ex nihilo–out of a void. The main character, Henry, struggles both with himself and with figures looming out of darkness in “the interhuman church”—the world that must be built up from scratch after the war. It is uncertain whether the action is set in Henry’s dream or in a reality.

Marriage. Photo credit: National Theatre, Warsaw.

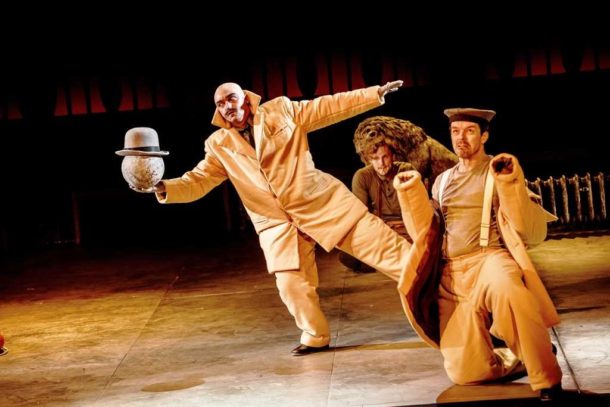

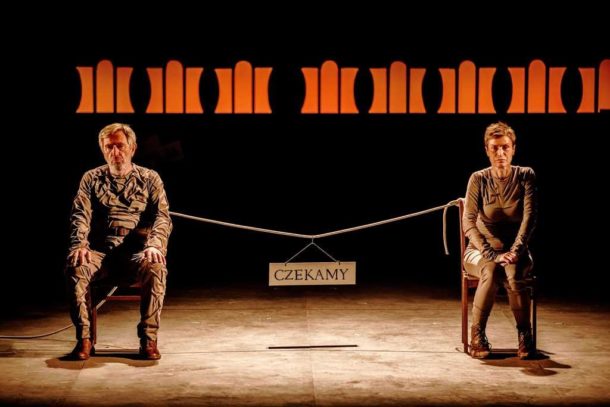

Unlike his Polish predecessors, Nekrošius slightly shifts the focus: from the creation of a subjective world, by saying only Henry’s words on the empty stage, to the objective, pre-existing onstage image of half a church, run-down half bar with the portrayals of ancestors on the walls (set design by Marius Nekrošius). This weird place has existed before the protagonist turns up. The center of the stage is occupied by Father (Jerzy Radziwiłłowicz who played Henry in Jerzy Jarocki’s Marriage in 1991) and Mother (Danuta Stenka). Their acting slightly differs from the realistic and psychological mode of acting that is deeply rooted in Polish theatre. Their acting is closer to a performative and corporal acting mode typical of Nekrošius’s theatre, where actors perform a series of theatrical exercises exploiting their bodies’ capacity in cooperation with the director. They express thoughts, emotions and desires through their physical actions on stage rather than focusing on the traditional realistic way. It resembles physical theatre, gymnastics or even circus shows. Scene by scene appear strange as Egyptian hieroglyphs in the eye of beholder, yet all physical actions of actors in fact reflect the characters’ inner life, their psychological depth. What is significant is that this mode of acting corresponds perfectly to the subject matter of Marriage: the individual’s struggle against Form, wrestling with social rules which in a way become integral to the characters’ bodies. In the initial silent scene added to the original text, Mother and Father start competing. They sit on two chairs, joined with a rope, with a Beckett-like sign that says “We are waiting.” The sign changes its content as a result of the constant fight between Mother and Father, their long-term relationship resembling a continual struggle.

Marriage. Photo credit: National Theatre, Warsaw.

In the way typical of his theatre, Nekrošius places metaphorical clues within the set design in his performance. At first, the spectator can see a pole with a traditional topping out—a symbol of the end of a building’s construction located there after the last beam is placed atop the structure. There is no doubt that Mother and Father constructed this house. When the decoration is knocked off by the Drunkard, the home undergoes destruction, meaning a return to existential homelessness. However, in the next part of the performance, an empty jar appears on top of the pole. Seamen in strange orange outfits (why seamen in this dream?) hoist an invisible flag up another pole in front of the stage and hum Yellow Submarine by the Beatles. The ship-home which has set to sail into the unknown now, apparently, is sinking (“And here comes my mother like a steamer” – says Henry).

Water has always constituted a principal element in Nekrošius’s theatre – both as a substance used by actors on-stage and as a metaphor. In Othello the protagonists, Vladas Bagdonas as Moor and Eglė Spokaitė as Desdemone, drown in the sea of love and hatred. In Hamlet, Ophelia appears as a fish who paradoxically drowns in the end. The examples can be multiplied. In Marriage the director follows Gombrowicz and emphasises (i.e. visualises as often as possible) the figurative sense of getting drunk (e.g. losing touch with reality due to occupying a high position in the social hierarchy) and sinking into social rules. Says Henry: “Oh, this sea of lights, this ocean of words/ And I’m drowning in it, drowning, drowning… like a drunkard.” It is as if social roles possess individuals, making them dangerous, so to speak, social “demons.”

The Drunkard – a profoundly Polish figure giving insight into the soul of the nation – does not function in this performance only as an individual case of a hooligan popping into high society. Also, Henry’s soul is overwhelmed by a struggle between a positive “constructor” of social order and a “destructor” – drunk particularly with power. The performance throbs between moments of creation and destruction, and the latter refers not only to the interhuman world but also to the theatre performance itself – in the moments when the play sort-of gets broken off. When Drunkard (brilliant Grzegorz Małecki representing the Lvovian gamin) pops on stage with clutter and throws a metal pole, the noise of which hurts our ears, both the stage home and the illusion of a proper performance (where “such things” do not happen) undergo destruction. There are more such moments of disillusion: somebody “unintentionally” tears off a side curtain, one of the characters refers to an object in their hand as a prop, somebody puts on an electric kettle that does not suit the stage design. Now and then the atmosphere is spoiled by characters such as a trumpet player or two disgruntled critics entering the stage.

All of this is in sync with Mateusz Rusin’s interpretation of Henry, who pops up into the world established by Mother and Father full of ambivalent desires: to create from scratch or to destroy, to be a model son and, at the same time, the black sheep of the family. Henry shows his excessive naivety by being constantly surprised at the surrounding reality or by believing that he is the one who alone has freedom of action. In this absolutely theatrical game he still keeps control over his fate. He seems sometimes to be a puppet overwhelmed by the theatrical illusion of social reality, while at other times he appears as a master of puppets ruling over the whole world, no matter theatrical or genuinely real. The viewer can’t be sure when this game will be over.

Marriage. Photo credit: National Theatre, Warsaw.

Other Nekrošius superheroes, such as Hamlet, Macbeth and Faust, take the same attitude in the metaphysical struggle between Good and Evil. Indeed, here in Marriage, all events take place within the interhuman church, in the world where God does not exist. Nekrošius would not be himself if he did not introduce the motif of human approach to the metaphysical world, which is a major theme of his theatre. The combination of Gombrowicz’s idea of Form and Nekrošius’s concept of bodies as containers filled with souls made of water/ ice/ steam, seems extremely productive and brings a fresh interpretation of Marriage. Spectators of Nekrošius’s Hamlet, that premiered in 1997, certainly remember the scene of King Claudius’s confession – his fingers digging into two glass cups filled with water. In Marriage, an empty jar appears on the pole in the last part of the play. The jar represents pure, soulless form filled with air. “So there is no ghosts? / The world has got no soul?” – asked Mickiewicz, the greatest of Polish poets.

It brings to mind the picture of the electric kettle which suddenly belches out a thick puff of steam. Initially Marriage in the Nekrošius’s interpretation represents the world of spiritual matter. As the time passes, the world undergoes a weird de-spiritualization and turns into a universe of empty forms. Is this the reason why the courtly world in this production resembles so much the Warsaw salon from Forefathers’ Eve of Nekrošius? Is this a case for presenting in Marriage these ghastly, paper and marble costumes, or ordinary, old radiators? (Marriage, in its stage directions, includes such a commentary: “Costumes are magnificent but border on the burlesque”). Molly, Henry’s fiancée, lost her social status during the war, becoming a maid or even a whore, is standing first on an empty jar, later on two jars with red tissue in one and white in another (Mother’s and Father’s souls in national colors). These accents prove that the director in a way interprets Marriage surprisingly from the perspective of the mystic philosophy of Genesis by Juliusz Słowacki. In short: it is the story of the triumph of matter over spirit. A story of a human being overwhelmed by the reality of masks, costumes and forms, which can be escaped only by suicide (as Johnny does in the final scene). The picture of a jar in the hands of Henry, with an apple as sort of a heart inside, becomes clear. Henry takes the fruit out of the jar with a knife, when he hits upon the idea of impelling Johnny to suicide.

Hamlet by Nekrošius was heavy with moisture – literally. It resembled a metaphysical symphony, a paean in praise of nature and the spiritual world. In Marriage, all spectators are submerging deeper and deeper in a purely human world. The universe, at first full of dynamic interactions and pulsing with emotions, in the end turns into a monologue that is a rejection of one’s existence. In Gombrowicz’s play Henry says:

“I am not in need

of any attitude! I don’t feel

other people’s pain! I only recite

My humanity. No, I do not exist

I haven’t any “I”, alas, I forge myself

Outside myself, outside myself, alas, alas, oh, the hollow

Empty orchestra of my “alas”, you rise up from my void

And sink back into the void.”

At the end of the performance Father and Mother, Johnny and Henry sit in a quadrangle which constitutes a symbolic empty catafalque. At first, Henry and Johnny were Siamese brothers with hands joined with plaster. They had to separate, utterly break off the plaster bond. Moreover, after Henry persuaded Johnny into committing suicide, the non-human, cruel world is being buried. A brother has killed his brother. Only the void is left. What must have terrified the director about Marriage as a story of a modern world, an interhuman Mass, is the silence falling over this world:

“In those days, gentlemen, a man would sit down

To a freshly laid table, and tuck away his pea soup

With such appetite and zest, one would have thought

He were ringing the bells or blowing a trombone.”

The trumpeter, walking before that behind and on stage as an intruder spoiling both interhuman and theatrical performance, now is not able to produce a single sound with his trumpet. As if the world has ceased to exist together with the last but one human being who gave the chance of inter-subjectivity, or a dialogue. The trumpet player blows his instrument and … nothing. There is only “the empty orchestra of my ‘alas’” in the brave, new, monadic world. Henry created this contemporary, de-spiritualized, call it post-human world, where we are living right now, on the ruins of the traditional world of his forefathers, that existed before the war. And the Lithuanian poet of theatre leaves us with no doubt what he thinks about this new reality.

Artur Duda (born 1973) is a theatre and performance researcher at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland. He is the author/editor of 9 books on contemporary Eastern European theatre (e.g. Grotowski, Kantor, Nekrošius) and theories of live and mediatized performance. Besides being a theatre reviewer, he is a constant collaborator of the Polish monthly “Teatr” and quarterly “Pamiętnik Teatralny”. He is head of the Revisory Commission of the Polish Society for Theatre Research (PTBT), member of Gesellschaft für Theaterwissenschaft (GTW) and FIRT/IFTR. He is a regular collaborator of the Center for Eastern European Theatre founded 2018 by Shanghai Theatre Academy.

European Stages, vol. 13, no. 1 (Spring 2019)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Introductory Note by Kalina Stefanova.

- “Andrzej Tadeusz Wirth (1927 – 2019) – White on White” by Krystyna Illakowicz.

- Lithuanian Marriage in Warsaw or The Last Production of the Great Eimuntas Nekrošius by Artur Duda.

- “My, Żydzi polscy [We, Polish Jews]”: A Review of Notes from Exile by Dominika Laster.

- A Report on the State of Our Society, According to Jiří Havelk in The Fellowship of Owners at VOSTO5, Prague, and Elites, at the Slovak National Theater, Bratislava by Jitka Šotkovská.

- About Life as Something We Borrow. On the Stages of Pilsen (In the 26 th edition of the International Theatre Festival There) by Kalina Stefanova.

- Redesigning Multiculturalism or Japanese Encounters in Sibiu, Romani, The Scarlet Princess, written and directed by Silviu Purcărete, inspired by Tsuruya Namboku IV’s Sakura Hime Azuma Bunshô by Ion M. Tomuș.

- About Globalization: A “Venice Merchant” on Wall Street, at the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj in Romania by Maria Zărnescu.

- The Patriots, Mary Stuart and Ivanov and the Rise of the Drama Ensemble of the National Theatre in Belgrade by Ksenija Radulović.

- The Unseen Theatre Company or How to See Beyond the Visible: The Shadow of My Soul and the Theatre of Velimir Velev by Gergana Traykova.

- Multilingual Pirandello, Understandable to Everyone: The Mountain Giants at the Croatian National Theatre “Ivan pl. Zajc”, Rijeka by Kim Cuculić.

- The return of the repressed: the ghosts of the past haunt Barcelona’s stages by Maria M. Delgado.

- A poetics of memory on the Madrid stage (2018) by Maria M. Delgado.

- The Danish National Theatre System and the Danish National School of Performing Arts: December in Copenhagen 2018 by Steve Earnest.

- Towards a Theatre of Monodrama in Turkey 1 by Eylem Ejder.

- Where Is Truth? Justiz by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, adapted and directed by Frank Castorf at the Schauspielhaus Zürich by Katrin Hilbe.

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson.

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019