There was a time when a traveler to Berlin in late June would have faced a much-reduced selection of theatre offerings, but today most of the major houses are still presenting a full selection of attractive works at that time. The notable exception is the Volksbühne, still in turmoil after a turbulent season. The replacement as director of the legendary Frank Castorf by Chris Dercon, a former director of the Tate Modern in London with little theatre experience, was bitterly opposed by many who saw this appointment as a central symbol of Berlin’s turning from the politically engaged and locally rooted work of Castorf toward commercialization and globalization. 40,000 people signed a petition urging a reconsideration of the appointment, the building was briefly occupied by protesters and anti-Dercon signs and banners dotted the area around the theatre.

Dercon gave fuel to his enemies by mounting a series of ambitious but unsuccessful productions, headed by the first major world premiere of the new administration, a play by Catalan film director Albert Serra that drew universal condemnation. In addition to this, expenses of the theatre rapidly rose as audiences disappeared. On April 13, Dercon’s contract with the city was severed and the theatre left without a director. Remnants of the failed Dercon program were still being offered in June, but the theatre had essentially disappeared from the consciousness of the public as it remained in limbo awaiting the selection of a new director.

The current situation at the Berliner Ensemble provides a welcome contrast. In the fall of 2017, Claus Peymann, who had directed the theatre for eighteen years, was followed by Oliver Reese. Reese was a far safer and more acceptable choice, already familiar to Berlin audiences from his work as dramaturg and interim director at several leading theatres, most recently as head of the Schauspiel Frankfurt. One of the first major productions of the new administration was the kind of offering the somewhat old-fashioned Peymann would never have considered – Castorf’s first work since leaving the Volksbühne, an eight-hour stage adaptation of Hugo’s Les Misérables.

Many of the elements of this sprawling work were familiar to those who remember Castorf’s previous productions, especially those of the 1990s. A complex architectural warren was erected on the turntable of the BE stage, quite reminiscent of the large maze-like buildings created for Castorf by Bert Neumann, who died in 2015. When the audience entered, they saw what seemed a fairly conventional setting, the two-story façade of a building, an ornate Spanish neocolonial structure proudly identified by the legend on its upper story: “fábrica de tabaco.” Knowing Castorf’s love of layering elements from other dramatic and non-dramatic sources into his productions, I spent much of the first half hour looking in vain for references to the music or story of Carmen. Not until I consulted a program during the first intermission was the mystery solved.

It seems that Castorf and his dramaturg Frank Raddatz, seeking a more contemporary context for Hugo’s novel, which is set against the brief June uprising of 1832 in Paris, found this in the period in Cuba just before the Castro revolution. Castorf particularly relied on images and references from a 1965 novel by Cuban author Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Three Sad Tigers, set in this period. Cuban music provided the basic sound of the production, the costumes by Adriana Braga Peretzki were Cuban based and the neocolonial façade that I had thought suggested Spain, actually referenced Havana, described in the program as “the Paris of the Caribbean.” When the façade revolves out of sight, however, revealing a warren of stairways, rooms and passageways, the most distinct element revealed is the crude gateway to a prison compound with warning signs in English. The reveal is clearly evoking a very different Cuban icon, one highly relevant to the themes of the novel and production, the U.S. prison at Guantanamo.

It was not until ninety minutes into the production that Hugo, or more specifically his protagonist, Jean Valjean (played by Andreas Döhlet), made his entrance as if from another world. The Cuban music, which had played constantly up to then, fell silent as his tall figure in a dark trenchcoat emerged from the darkness of the auditorium. Mounting the stage, he enters a small area, almost like a cell, and asks an old man sitting there for shelter. He delivers a lengthy speech which summarizes the early part of Hugo’s novel, about his nineteen years in prison and the oppressive conditions of contemporary society. The old man, not responding to him directly, but seated facing the audience, embarks on an even more extended speech defending the ideals of the Enlightenment and the clearly impending revolution necessary to fulfill them. Gradually we come to recognize that this is the bishop with whom Valjean seeks shelter and whose compassion leads to his salvation. The bishop is played by the great Jüurgen Holtz, now 86, a pillar of the Berliner Ensemble and indeed of modern German stage and film. His dinner with Valjean and his subsequent sacrificial gift of the candlesticks, perhaps the best known sequence in the novel, is presented not as a stage action but as a live video sequence taking place in an elegant realistic dining room within the complex set, that the cameras record but which the audience never sees directly. In this extended scene, the loving closeups of Holtz’ craggy features clearly reveal his power as a film presence, and solidify his performance as the outstanding one in a production with many distinguished actors.

Since the 1990s, Castorf has been particularly associated with the mixing of live performance and live video, and has often included lengthy sequences accessible to the audience only by large monitor screens hanging above the stage, but I had never seen this mixture used so extensively or effectively as he did in this production. Moreover, these sequences employed traditional cinematographic techniques to an extent I had not seen before in his work. In the past, the live video usually operated in a casual, almost improvisatory manner, as if the camera operators, like newsmen covering a breaking story, simply pointed their cameras at whatever or whoever seemed most interested. Here, on the contrary, the video images, though still live, were carefully composed, using such traditional film devices as alternating over-the-shoulder shots in a dialogue, or framing of one actor face-on between two profile discussants. The result was a production that in many spots seemed far more like traditional film than I have previously seen from Castorf.

Les Misérables. Photo: Matthias Horn.

Indeed, in the latter part of the production, which followed Hugo somewhat more closely, the filmic sequences often closely resembled, and in a few cases directly quoted from, the tradition of film noir. This impression was strongly reinforced by the theatrically powerful, if consciously melodramatic, interpretation of Wolfgang Michael as Valjean’s dogged antagonist, the policeman Javert, who concluded the long evening with a monologue of confusion and regret as he sunk away, a suicide, into darkness.

Among the women in the production, Vlery Tscheplanowa stood out as the much-suffering Cosette, as did Stefanie Reinsperger as the debased Mme Thénardier, but it was the men who carried off the honors of the evening, beginning with those already mentioned and adding Ajoscha Stadelmann, Reinsperger’s partner is corruption. Perhaps the Berlin Ensemble surroundings affected my reception, but the Thénardiers seemed to me a kind of apotheosis of Brecht’s Mr. and Mrs. Peachum, and when they took over the main focus of the production in the second part, I almost expected them to burst into Peachum’s morning chorale or “Instead of.”

As has often been the case with Castorf productions, there have been predictable complaints about the length of the work, the self-indulgence of the production choices, the use of remote and often obscure references, but, as always, there were also many moments and sequences of remarkable power, both visually and intellectually, some due to the director, others to his designers, and still others to his outstanding cast. I think most viewers would have been equally content with the removal of a couple of hours from this demanding work, but Castorf, like Hugo, is in no hurry to rush his story or his message, and ultimately I felt the match was a successful one.

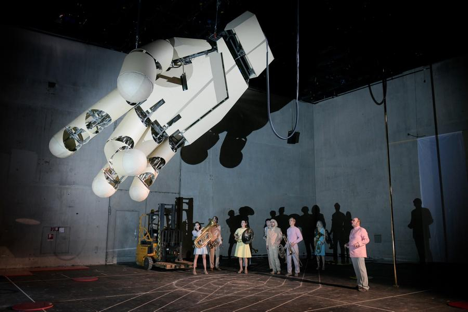

Null. Photo: Matthias Horn.

One of my favorite directors on the contemporary German stage is the imaginative Herbert Fritsch, one of the greatest creators of physical farce comedies in the world today. His newest work, with the typical title Null (Zero), opened at the Berlin Schaubühne in March. The opening of the production reinforced its title on several levels. The doors to the theatre did not open until more than 15 minutes after they announced curtain, and upon entering we saw an essentially empty stage, with blank if colorful walls, a single door at the rear, a pole downstage reaching into the flies and a small pile of dark fabric stage center. Another ten minutes passed before anything happened, when Fritsch’s company (six men and three women, in colorful but not elaborate costumes), came spilling out of the upstage door, exchanging heated but largely incomprehensible comments. Eventually, they lined up across the stage and one of their number pulled apart the dark pile, revealing body harnesses which each put on. A line of wires came down from the ceiling, to which each actor attached him or herself, and they were lifted into the air, setting off a long series of ingenious and very funny individual and group movements in space. Fritsch loves playing with the weightless bodies, and jumps and trampoline bounces have always been popular with him, so these routines, even including actors bouncing off each other and crashing through the walls out of sight, were very much in his comic style.

Although I found this sequence particularly delightful, a variety of other imaginative physical actions followed. For much of the evening a forklift truck was incorporated into the dance sequences, with individuals or groups being lifted, lowered, or carried about on its extended prongs. At one point, all but one appeared with brass instruments, and, lovingly conducted by the ninth, they produced either no sound at all, or simply magnified blowing or breathing. The pole was of course used for a variety of climbing, sliding and combined routines. All of this was engaging, surprising, and often very funny indeed, but the pace and the humor were not as well sustained as in the best Fritsch productions. There are long rather blank stretches between the routines, and several of them go on well past the period when their novelty and humor is exhausted. A giant mechanical hand, which is brought onstage and raised into the flies with considerable effort at the beginning of the second part, has one brief and entertaining moment when it lowers and encloses the company, but then it goes back to the ceiling and remains there the rest of the evening, twitching from time to time but never delivering an action that would justify its monumental presence. The evening delivered, as Fritsch always does, excellent if somewhat light entertainment, but not in the highly concentrated form he often achieves.

My third evening, at the Deutsches Theater, Berlin’s other leading house, was the most disappointing. This was a staging of Williams’ The Glass Menagerie by Stephan Kimmig, a frequent guest at this theatre and other leading German houses. Although Kimmig’s production followed the general lines of Williams’ play, he seemed determined to take it in original directions, but never in ones that seemed to me either clear or justified. The stage setting, by Kimmig’s frequent designer Katja Haß, seemed to suggest the interior of an abandoned warehouse, with sewing machines along one wall. Folding chairs and tables were brought away from the walls when needed, but there was not a sense that this was in fact a place where anyone lived. The four actors were clearly skilled and threw themselves into their parts with great (sometimes excessive) energy. Much of this seemed to me misdirected. I found Tom (Marcel Kohler) the most successful, partly because his morose and ironic underplaying seemed more human and understandable than the rest. Laura, played by Linn Reusse, had her “deformity” rather inexplicably changed to blindness, or, to be more accurate, near-sightedness, since she managed completely well without her glasses. Why this should have been a serious problem for her is never clear. By far the strangest and most inexplicable interpretation though was provided by Anja Schneider as Amanda. Schneider, who has often worked with Kimmig, tends to present extreme characters, but I have not seen her go to the lengths she does here. From the very beginning she is almost out of control emotionally, staggering about the stage, rolling her eyes, and bestowing sloppy sexual kisses upon any male she can grasp. Before long I decided she was supposed to be on drugs, but why this should be so was never clear. All the characters were encouraged by Kimmig to improvise lines and actions, but only in her case did this seem to spin out of control.

The arrival of the gentleman caller (Holger Stockhaus) finally imposed a more consistent tone on the production, which had been veering rather wildly, but it was a rather unexpected one – of flat out slapstick. The high point of the evening, beautifully done, was the scene of the four characters all sitting on the table and attempting to carry on a normal conversation as Amanda and Jim, seated facing us, carried on an extended attempted seduction if not rape of Jim, while the children, seated in profile on the two ends of the table, reacted with a stunned if quite understandable mixture of disgust and horror.

The Glass Menagerie (Tom, Jim and Laura). Photo: Deutsches Theater.

Perhaps the sequence that best summed up the production for me was that where Jim says, “somebody ought to kiss you, Laura,” and then proceeds to do so, followed in Williams by confused embarrassment on both sides. Here the kiss was not at all gentle or offhanded, but full-blown and erotic, followed by two even more passionate kisses, with intense passion on both sides. Then both Jim and Laura begin tearing off their clothes, getting down to their undergarments, before Jim comes to himself and moves away. I commented to my companion in the audience, “Ah the German theatre,” and if that was a bit unfair, it does indeed reflect my occasional exasperation with directors, and Kimmig has been often among them, who seem to feel that the best approach to the classics is what some of them incorrectly call “deconstruction,” and which all too often falls back on clichés like the emotional excesses of Amanda here or the sexual excesses of the entire company.

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is a theatrical autobiography, 10,000 Nights, University of Michigan, 2017.

European Stages, vol. 12, no. 1 (Fall 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 (Part II) by Beate Hein Bennett

- Report from Berlin (June 2018) by Marvin Carlson

- Othello, Shakespeare’s New Globe by Neil Forsyth

- Resistance Through Feminist Dramaturgy: No Way Out by Flight of the Escales by Meral Hermanci

- 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe by Anna Jennings

- The Avignon Arts Festival 2018 (July 6 – 24): Intolerance, Cruelty and Bravery by Philippa Wehle

- Le Triomphe de l’Amour : Les Bouffes-du-Nord, Paris, June 15—July 13, 2018 by Joan Templeton

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018 of Brussels (Belgium) by Manuel García Martínez

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Contemporary Nordic Performance at the 2018 Arctic Arts Festival by Andrew Friedman

- A Piece of Pain, Joy and Hope: The 2018 International Ibsen Festival by Eylem Ejder

- The 2018 Ingmar Bergman International Theater Festival by Stan Schwartz

- A Conversation With Eirik Stubø by Stan Schwartz

- The Estonian Theatre Festival, Tartu 2018: A ‘Tale of the Century’ by Dr. Mischa Twitchin

- BITEF 52, World Without Us: Fascism, Democracy and Difficult Futures by Bryce Lease

- Unfamiliar Actors, New Audiences by Pirkko Koski

- Corruption, capitalism, class, memory and the staging of difficult pasts: Barcelona theatre and the summer of 2018 by Maria Delgado

- Reframing past and present: Madrid theatre 2018 by Maria Delgado

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018