After accepting an invitation to sit on the jury of BITEF 52 (Belgrade International Theatre Festival) in 2018, I read through the list of previous prizewinners. The history of the festival is a history of European theatre, reflecting its many phases, trends, obsessions and preoccupations, its play with form and style, its relationship with actors and acting and audiences. Jerzy Grotowski won the very first Grand Prix in 1967 with his now legendary production of The Constant Prince. Moving through the late 1960s, the prize went to Víctor García, Peter Gill and William Gaskill with the Royal Court, Richard Schechner with the Performance Group, and Peter Schumann with Bread and Puppet Theatre. The 1970s offer a striking portrait of artistic invention, neo avant-gardes and political engagement. Here is Ingmar Bergman, Joseph Chaikin, Ariane Mnouchkine, Merce Cunningham, Peter Stein, Peter Brook, Eugenio Barba, Konrad Swinarski, Andrei Serban, Roger Planchon, Robert Wilson, Tadeusz Kantor, Pina Bausch and Lindsay Kemp. The 1980s and 90s add more renowned names, many from Central and Eastern Europe, whose achievements moved from the classical canon to auteur theatre (what Peter Boenisch has referred to as Regietheater), such as Andrzej Wajda, Jerzy Jarocki, Frank Castorf, Eimuntas Nekrošius, Lev Dodin, Christoph Marthaler, and Josef Nadj. Whomever wins the annual Grand Prix and the Special Prize at BITEF joins this prestigious list; the weight on a jury member’s shoulders is not a light one.

While his predecessor selected productions before deciding upon an overall theme for the festival, BITEF’s current artistic director, Ivan Medenica, reversed this curatorial gesture. First composing a motif marked by allegiance to a socio-political current or artistic strategy, Medenica travels through Europe in search of performances that illuminate his overriding concept. The slogan for 2018 was ‘Svet bez ljudi’, which can be translated as ‘World Without People’ or ‘World Without Us’. Medenica preferred the latter translation, as this speaks to the apocalyptic rise of extreme rightwing politics and fascism today that could ultimately result in the total destruction of human culture and populations. Companies and directors were invited from across the continent and beyond, including Slovenia, France, Serbia, Germany, Croatia, Estonia, Switzerland, Belgium, and Israel. Exploring themes of non-tolerance and authoritarianism, there were a number of productions that dealt with the experiences of social marginalization that produce fascistic movements and the prejudices that feed them, as well as the complicity of capitalism and neoliberalism in these political trends.

Odilo. Obscuration. Oratorio. Mladinsko Theatre, Kino Šiška Centre for Urban Culture, Ljubljana, Slovenia. Directed by Dragan Živadinov. Photo: Nada Zgank.

Revisions of history loomed large. The festival opened with Odilo. Obscuration. Oratorio. Co-opting fascist aesthetics, Odilo was produced by Ljubljana’s Mladinsko Theatre, whose artistic director, Goran Injac, has been producing a dynamic transnational program since returning to his native Slovenia after many years working as a dramaturg in Poland. Directed by Dunja Zupančič, more recently known for his experiments in postgravity art, Odilo returns to the aesthetics of Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), the political art collective formed in the mid-1980s that produced Laibach, controversial and well-loved for their evocation of fascism as a form of its own critique. Zupančič was one of the co-founders of NSK, and although this movement had significant if divisive impact in its first two decades, the artistic strategies (the play between irony and the reenactment of Nazi rallies; idealization exaggerated to the point of satire) today appear to be more a reminder of a different era than an urgent form of opposition. Zupančič and dramatug Tery Žeželj curated a script from a number of sources, including historical speeches from the archive, to first invoke and finally expunge the memory of Odilo Globočnik, a close ally of Hitler and senior ranking member of the SS who played a leading role in Operation Reinhard. Globočnik has traditionally been remembered – though he has largely been forgotten – as an Austrian. Zupančič reveals that Globočnik is a fellow Slovene, and thus punctures a hole through forms of national(ist) identity that easily position Slovenia as progressive and historically anti-fascist. ‘We never learned that as part of “our” history,’ Zupančič explained. A chorus chants in rhythm in pseudo-fascistic military apparel, not to celebrate but to annihilate Odilo’s name. On large banners and armbands an icon of a globe references Globočnik’s name and also signals the global implications of the return of the extreme right. In the after-show talk, dominated by Zupančič’s meandering if humorous anecdotes, the director observed that he would not use a word such as fascism (‘that is a euphemism!’) when Europe today is actually once again facing the return of Nazism. While I understand the impulse to erase a difficult past as a gesture of resistance to this historical return, something in this performance also made me cautious. Now that Odilo’s name is officially erased from the record, do we allow him to fade away? Shall we forget him a second time? Erasure and exculpation often go hand in hand in the archive.

Suite No 3 Europe, Encycloédie de la Parole, Paris, France. Directed by Joris Lacoste. Photo: Frédéric Lovino.

The official opening production of the festival was Suite No 3 Europe, directed by Joris Lacoste and composed by Pierre-Yves Macé as part of the Encyclopédie de la Parole. A white curtain triangularly frames the bare stage, whose minimalism is punctuated by a large black piano. Translations are typically placed discreetly above the scenographic frame of the action, but in a performance that covers the official languages of 28 member states of the European Union the screen for the surtitles is set as the central focal point. Two performers, a woman and a man, deftly sing utterances taken from everyday life across the continent. Dialogue is sourced from sermons, life coaching sessions, hate speeches, reminiscences, job interviews, video blogs, phone calls. They are banal, they are xenophobic, they are frightening, they are trite, and they are funny. Set to music and performed in their original languages, these texts move out of their quotidian and culturally embedded contexts to question what it means to be European today. Their musicality moves them beyond simply mimicry. Skipping from a Spanish youtube video about grocery shopping to a Maltese politician’s xenophobic tirade, I found overlaps in rhetorical style, but was far more engrossed by the banality of a shopping list than by the repetition of political slogans. Taken as whole – this performance is surly more than the sum of its parts – Lacoste invites us to really listen to one another and to ask what the ethical value is of inhabiting others’ voices. Rather than uniting the audience, many moments in the performance drew attention to our differences (for example, the scattered applause that followed an anti-abortion invective), and made a compelling case for the real risks of freedom of speech. The jury was struck by the virtuosity of the performance team in Suite No 3 and particularly Bianca Iannuzzi, whose dynamic vocal and performance range no doubt helped the production to win the Audience Prize.

During the first weekend of the festival, director Oliver Frljić, who has previously won two prizes at BITEF for his confrontations with painful histories and unresolved politics in the Balkans, and philosopher cum political activist Srećko Horvat shared the stage of the Serbian National Theatre in an activity they called Philosophical Theatre. This forum was first initiated by Horvat at the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb in 2014. In their discussion, Horvat insisted that we should oppose tendencies to turn to solutions in the past that become even more dangerous in the future. He observed that in the age of Trump politics has not entered theatre but theatre has entered contemporary politics, and now performance makers have an ethical imperative to respond. Perhaps the most uncomfortable question from the audience addressed the coincidence but non-alignment between theatre and protest. Two nights’ previously, only a few streets away from the festival’s opening party, a protest had been organized against the current Serbian government. Three construction workers had fallen to their deaths while working on Belgrade’s new high-end but contentious waterfront district. The protesters spoke out on behalf of the workers – who had died in the name of economic efficiency and a lack of appropriate healthy and safety conditions – and demanded a stop to the capitalist speed of production that did not value the lives of laborers. One woman asked if we should have been in the theatre or at the protest – a question that produced an unresolved debate around political allegiances, the (non)impact of public protest, alternative forms of activism and the social responsibilities of theatres, audiences and makers.

Frljić’s primary observation was that democratic platforms are producing anti-democratic systems. As a result, it is his institutional critique of spaces such as national and nationally funded theatres that is the crucial political intervention needed today. Theatres must be political tools, Frljić argued, not just sites of presentation. When asked if he planned to work again on Serbian stages, Frljić replied that he would return on one condition: to direct a production about the current president, Aleksandar Vučić, known for his extreme rightwing, nationalist views and sponsorship of war crimes in the 1990s. ‘I have told everyone I will direct this production for free,’ Frljić explained. ‘The theatre does not have to pay me. So far, though, not one theatre has extended an invitation.’ Horvat and Frljić agreed that the war in the Balkans, though officially over, is being prolonged. The director purposefully misquoted Clausewitz’s famous idiom, ‘peace is the mere continuation of war by other means.’

Following the public debate, we attended Bollywood, the only Serbian performance selected for the main festival, written and directed by the hugely talented Maja Pelević. Purposefully frivolous and kitsch, the musical play (or self-branded ‘trash musical’) charts Serbia’s unending political transition and dependence upon and pandering to global entertainment companies, NGOs, the World Bank and the EU – all of which can be summed up in the single line, ‘Our country is for sale – 90% off!’ Tracing a non-linear line that traverses xenophobia, identity politics and progressive liberalism, the plot follows a local theatre company in a border town that houses migrants waiting to enter the EU. Having taken over a closed factory from the socialist period, the company awaits a Bollywood production company from India and a producer from Germany with the hope that tomorrow they’ll be ‘in a better state.’ The actors wear costumes painted with fake blue skies that perfectly match the backdrop of the stage. This optimistic, carefree, world of flat one-dimensional ‘blue-sky thinking’ (a term increasingly employed by marketing companies) contrasts starkly with their lived reality, full of petty tensions, daily humiliations, ethnic conflicts, and the travails of privatization. The fact that that no one ever shows up from abroad ultimately doesn’t matter, because as one character concludes, ‘We forget everything. We have the memory of goldfish.’ While the script was clever and the music sharp, the overtly ironic acting became grating and lost some of the critical bite and subversive resonance we would find in Frljić’s productions over the following two evenings. Bollywood’s humor and frenetic energy also contrasted with the movement-based performance No43 Filth by the renowned Estonian company, Teatar No99, whose exploration (in an actual bank of mud) of social isolation, fraught relationships and sustainable communities was carefully choreographed and visually arresting but largely unaffecting.

Frljić brought two very different performances to BITEF 52. Gorki – Alternative für Deutschland? (Maxim Gorki Theater, Berlin) produces a double critique of a progressive theatre institution attempting to offer visibility to ethnic minorities and the development in Germany of an extreme rightwing. His second production prompted much debate amongst members of the jury. Six Characters in Search of an Author (Kerempuh Satirical Theatre, Zagreb) is a performance of many unexpected turns. Only loosely connected to Pirandello’s original, Frljić opens with the actors wearing pig masks, a satirical staging of Croatia’s political and cultural elite. Their riotous dancing and snorting of cocaine as form of Holy Communion is interrupted by the eponymous characters in search of their author. As the action unfolds, all of the people on the stage begin to use their real names, making it difficult to distinguish between character, actor, and actor as character. Without explicitly depicting the MeToo Movement, the performance participates in its politics. Linda Begonja’s ‘character’ works as a prostitute and the director asks her to reenact the moment she first had to sell her body. This ‘act’ results in an attempted rape. Pleading with the rest of the ensemble of actors to believe that the director tried to sexually assault her, the audience is invited to question our own participation in the dynamics of institutional sexism in ensemble theatres. At the conclusion of the production, Begonja turns to the audience, having shot her fellow characters with a pistol, and asks, ‘Who is the author?’ The allusive ‘author’ might be us, the audience, or perhaps theatre institutions themselves that have ownership over the aesthetic language we trade in. Frljić has argued that we are stuck in the same modes of representation, a dominant theatrical language that prevents – rather than enables – artists from interrogating society.

Six Characters in Search of an Author, Kerempuh Satirical Theatre, Zagreb, Croatia. Directed by Oliver Frljić. Photo: Ines Stipetić.

Discussions following the performance were not only about the specificities of Croatian political and theatrical cultures, but also concerned the intricacies of dramaturgy, the difficult lines between reality and fiction, and the audience’s role in producing meaning. Frljić explained that because critics often focus on the political aspects of his performances they often do not speak about his theatrical language, which actually offers him further space and greater freedom for formal experimentation. In Six Characters, however, it was impossible to miss his play with dramaturgical tools that comes from a nuanced reading of Pirandello, a profound engagement with Croatian politics and a coalitional attitude to global movements. Ultimately, he mobilized Pirandello and an ensemble known for their skillful physical comedy to explore and question progressive political modalities in our theatre institutions.

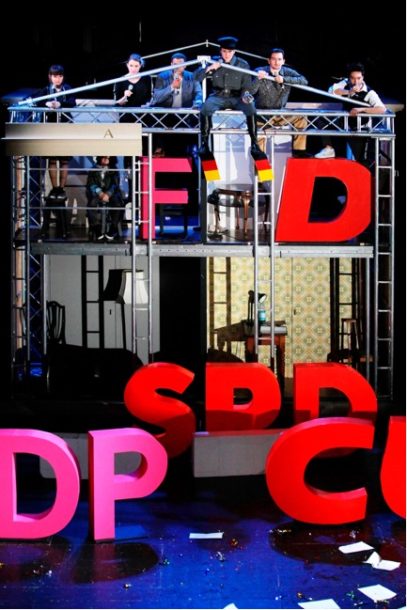

Gorki – Alternative for Germany?, Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin, Germany. Directed by Oliver Frljić. Photo: Ute Langkafel.

In Gorki – Alternative für Deutschland?, this institutional critique was funneled through a broader critique of German society and politics, which has recently seen the rise of a neo-fascist party (AfD) that has members currently seated in the Bundestag. In Philosophical Theatre, Horvat warned that what was impossible to say only a few years ago in a country like Germany (fascist slogans, overt xenophobia) has become a norm today, blandly tolerated by the general public. Şermin Langhoff, artistic director of the Maxim Gorki Theater, picked up on this point in an after-show talk. Listing a number of political developments, from the implementation of a new police law not seen in the country since the Third Reich to the inauguration of a Heimat Minister in Bavaria, Langhoff pleaded with the audience to take heed. As with so many of Frljić’s performances, often dominated by crowds of protestors representing the conservative right as well as neo-Nazis, the outside/inside dynamic of the theatre was not a simple binary of opposites. (For a further discussion of Frljić and the dynamics of protest see my article ‘What on earth is happening in Poland? On Klątwa, protest, and a new regime’ in CTR Interventions June 2018, available at https://www.contemporarytheatrereview. org/ 2018/lease-what-on-earth-is-happening-in-poland/.) As we entered the Belgrade Drama Theater, a local activist held a sign that read ‘Death to Bourgeois Culture,’ while inside the auditorium audiences were confronted with the slogan, ‘Courage to Tell the Truth’. I was tempted to read these assertions against one another, though I ultimately found both to be axiomatic. The title Gorki – Alternative für Deutschland? is already a provocation – an impossible pairing of the xenophobic political party with the progressive theatre company they hope to defund. Frljić invited the actors to join the far-right party so that they had voting rights from within it, using the theatre’s public funds to pay for their memberships. This action – which divided the ensemble, many of the actors refused to participate – confronts ‘victim status’ on German theatrical and political stages. Starting with the Gorki Theatre’s casting call for actors with an immigrant background, the focus turns to the victimization of the two white actresses in the company (named the Exiles Ensemble) who compete to keep their position in the company. The audience, who readily participate in the proposed action, is invited to applaud for the actor’s tales of woe (one suffers from a violent immigrant stepfather, the other is raped by her Syrian refugee partner) they find more convincing, with the understanding that the woman who receives less support will be forced to leave the Gorki. The stories of white, ethnic German suffering remerged in the AfD’s call for the recognition of triumph and victory in German history and not only the humiliations of National Socialism. A scale-sized model of the Gorki Theatre slowly creeps forward on the stage and then is taken apart, piece by piece. This literal deconstruction of the institution reveals actors concealed inside, separated and isolated, giving voice to the Angst felt by AfD voters that is later reformulated through an actual, and actually terrifying, speech from an AfD politician. Pointing out the politics of casting as a form of structural racism and the right for certain actors to speak on German stages to the exclusion of others (only those who speak fluently and without an accent have access to the Deutsches Theater, for example), we see how quickly and insidiously an alternative for Germany might become an alternative for Europe. Frljić confronts us with our collective complicity in this transition. If some audience members were outraged by the use of the neo-right’s rhetoric to critique the Gorki’s diverse ensemble, others saw the Gorki’s readiness to critique its own practices as a form of subversive affirmation.

In the jury’s final meetings, we debated three performances that worked without actors. These productions provoked us to question the limits of theatricality and the dynamic overlaps between scenography and visual arts, the live and the mediated, the present and the absent. A young Israeli multimedia artist, Nadav Barnea, made his theatrical debut at the festival with a meditation on memory. Pa’am hypnotized audiences with a series of confessions about guilt, nostalgia, adolescent sexuality, inherited trauma, and Holocaust memory, interwoven with disorientating choreographies of light, bits of archival video footage, and voluminous sound. These stage elements came together as an elegant engagement with postmemory. History was addressed again in Eternal Russia, an example of the critic taking up the role of the artist. Marina Davydova in collaboration with scenographer Vera Martynov took ownership of the artistic space and expression in a brave confrontation with the current dynamics of Russian politics and society, which they situated in a framework of historical upheaval and revolution. As Judit Csáki, the president of the jury, observed, Davydova and Martynov showed us this unique perspective of history that points beyond Russia to a broader question – what happens politically when the wheel of history is turning backwards?

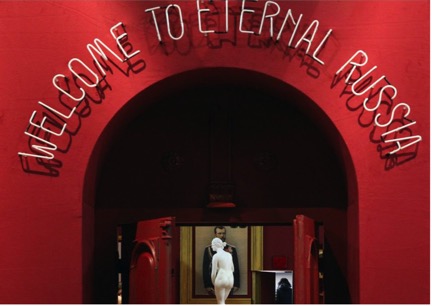

Eternal Russia, Hau Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin, Germany. Authored by Marina Davydova and Vera Martynov. Photo: Dorothea Tuch.

The immersive installation moves between a throne hall called ‘Eternal Russia,’ and a series of outer spaces deceptively named ‘utopia,’ While the utopias each have their historical specificities that disrupt or challenge forms of authoritarianism and totalitarian thinking, Eternal Russia remains a large and imposing imperial room. In the beginning, this room is complete with a portrait of the Tsar, classical European artworks, religious icons, portraits of important figures and aristocrats. Each time we return to the throne hall, as history ‘progresses,’ these same elements change, and – in important ways – remain the same. The Tsar becomes Stalin, and in the Putin era, a reflection of both men are present, reminding us that the current authoritarian government is made up of elements of both monarchist and communist pasts. In the final moments, repeated portraits of Putin dominate one wall; only on closer inspection did I realize these were fakes, a subversive artist impersonating the Russian leader. On the one hand, this insinuates that the whole production is an assemblage of fake objects – there are none of the originals of a museum collection here. However, the power of the performance did not result from a confrontation with the notion of the original and its attendant aura. For me, one of the most memorable stage elements was a table of Jewish objects in the first iteration of the room. These are eventually covered up with a USSR flag, before they simply disappear. I wondered how many people even noticed their disappearance. So much of history is obscured by the triumphant, by the loud, by the bombastic signs of empire, but it was this attention to the small, the nuanced, and the quiet details of loss and disappearance that made the performance the most impactful, the most heart-breaking, and the most politically defiant. While we focus all of our attention on the pompous patriarch, what is obscured from our sight?

The final two performances of the festival moved from the intimate to the epic. Rimini Protokoll’s Nachlass, pièces sans personnes was an instantiation of legacy, the personal effects that we leave after our deaths. The audience enters a communal area dominated by a map on the ceiling with tiny lights that mark human deaths occurring in real time across the globe. A series of simple wooden doors surrounds us, each with a clock counting time (our ‘life’ time, our time inside the room, our time waiting outside). In the first room I come into – there is no prescribed order, you may choose to enter or to avoid any room you wish – there are cardboard boxes full of books, records, African artworks and jewelry. This is the Nachlass of a French diplomat. I accidentally leave my jury notes in the room and an audience member files them away in one of the boxes when instructed to leave the room as we found it. Later, I locate my notes by chance beneath the diplomat’s heavy books and personal folders. This is a reminder that we never ‘leave the room as we found it’ but always somehow manage to insinuate ourselves into the remains. The rooms are curated as a series of intimate stories from those about to die (from assisted suicide, from dangerous hobbies, from cancer), who wish to be remembered, and who, for the most part, wish to be remembered fondly – including the elderly German couple who admit that as teenagers they noticed the Jews disappearing from their town and did not feel or do anything. One room included a technically breathtaking series of mirrors that reveal and overlap our faces with the faces of our fellow spectators as a British scientist explains the slow and inevitable deterioration of the human brain. He does not believe in an afterlife, while an elderly Muslim man in the next room explains that life after death is far more significant than our mortal years spent on earth. Another room is full of photographs, a material record of a life, while the scientist finds the indexical quality of photographs fail to represent his life adequately. They are not included in his Nachlass. A door opens and I hear – briefly, only for a moment – the singing voice of a woman who is already dead; she says goodbye. Above me on the map of the world the light slowly illuminates another human life that has just been extinguished. A World Without Us.

Requiem for L., Company les ballets C de la B, Ghent, Belgium. Directed by Alain Platel. Photo: Chris van der Burght.

The final performance, Requiem for L., from the company les ballets C de la B (Ghent), opens with an empty stage dominated by rows of long flat gray levels of various heights that immediately index the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin. However, rather than attributing these stage elements to the European memorial, the production offers a more ambiguous confrontation with non-European forms of memory and memorialization by largely African artists. A slow-motion video of a white Belgian woman in the last moments of her life at the back of the stage dominates the performance frame. Slowly, one by one, fourteen musicians arrive, moving across, over and through these gray levels as they perform Fabrizio Kassol’s score, which takes many forms, from opera and jazz to Mozart’s Requiem, to various forms of African music and popular musical traditions. The high mournful tune of an accordion suddenly gives way to an aria that is interrupted and shaped by the deep rumble of drums and a bass guitar. The musicians wear the garb of mourning, but their black suits paired with Wellington boots (perhaps a storm is coming?) eventually open up to reveal brightly colored shirts. The requiem as a funeral rite is the requiem as celebration. While this might at first appear to be an assemblage of unrelated fragments, the performance builds force precisely through this shift in forms and moods, which is recalibrated by what I first interpreted as a tension between the video and the performers until the moment when the performers joined the audience in the act of watching the video, of witnessing this woman dying. When one musician plays his small tuba, the woman on the screen opens her eyes. Is she also listening to us? Her presence is not merely spectral. There is room for a postcolonial reading of this encounter, which charts the death of one world and the dynamic instantiation of another that counters chronological or normative temporality. This rite is coalitional and multiracial. In this way, the production cannot simply be read within the confines of its representational acuity; rather, mourning becomes a process of world-making.

Perhaps today prizes seem old fashioned, something of the past. Why give these out today in an era of progressive politics that places its energies into alliances rather than hierarchies? On the other hand, there is power in a prize. While a Grand Prix or Special Prize might merely be added to a lengthy CV of Europe’s most established directors, it can have an enormous impact on a younger or emerging artist. So, the question we asked ourselves as the jury was not only who deserves the prizes, but what do the prizes do? Looking across the program, the jury saw many special forms of engagement. Confronted by the absence of actors, we were persuaded and moved by the work of two Russian women, who bravely confronted their own histories, and the subtle interrogation of death that considered questions of belonging, the right to self determination, and the dynamics of legacy – both of what we leave behind and the way we choose to leave it. The Grand Prix for 2018 went to Rimini Protokoll’s Nachlass, while Eternal Russia and Requiem for L. were given Special Prizes.

Perhaps the term that came up the most in our discussions was ‘engaged.’ It is a word that moves forward the discussion of the political today, and which we saw embedded in the festival in many forms, some explicit and others much more subtle, difficult to locate. The rise of fascism today is insidious but it is also very apparent. These performances reminded us that the political task of theatre today may not be to teach us what we do not already know, but to confront us with the fundamental problem that we do not engage with what is in front of our faces. Leaving Belgrade at the conclusion of the festival, I was reminded of a comment Frljić had made: the memory of the Second World War is no longer adequate as a form of resistance to the current rise of the extreme right. Now, theatre makers must confront the blatant fact that democracy does not have a mechanism to prevent the return of fascism. Do we?

Bryce Lease is Senior Lecturer in Drama & Theatre at Royal Holloway, University of London. He has published widely on Polish theatre, including his recent monograph After ’89: Polish Theatre and the Political (2016). He is a member of the editorial team for Contemporary Theatre Review, and is currently co-editing Contemporary European Playwrights (Routledge) with Maria Delgado and Dan Rebellato and A History of Polish Theatre (Cambridge University Press) with Katarzyna Fazan and Michal Kobialka. Between 2018-21, he is Primary Investigator for the AHRC-funded project ‘Staging Difficult Pasts: Of Narrative, Objects and Public Memory’. The research for this article was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant number: AH/R006849/1), and Lease’s attendance at BITEF was supported by the festival organizers.

European Stages, vol. 12, no. 1 (Fall 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 (Part II) by Beate Hein Bennett

- Report from Berlin (June 2018) by Marvin Carlson

- Othello, Shakespeare’s New Globe by Neil Forsyth

- Resistance Through Feminist Dramaturgy: No Way Out by Flight of the Escales by Meral Hermanci

- 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe by Anna Jennings

- The Avignon Arts Festival 2018 (July 6 – 24): Intolerance, Cruelty and Bravery by Philippa Wehle

- Le Triomphe de l’Amour : Les Bouffes-du-Nord, Paris, June 15—July 13, 2018 by Joan Templeton

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018 of Brussels (Belgium) by Manuel García Martínez

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Contemporary Nordic Performance at the 2018 Arctic Arts Festival by Andrew Friedman

- A Piece of Pain, Joy and Hope: The 2018 International Ibsen Festival by Eylem Ejder

- The 2018 Ingmar Bergman International Theater Festival by Stan Schwartz

- A Conversation With Eirik Stubø by Stan Schwartz

- The Estonian Theatre Festival, Tartu 2018: A ‘Tale of the Century’ by Dr. Mischa Twitchin

- BITEF 52, World Without Us: Fascism, Democracy and Difficult Futures by Bryce Lease

- Unfamiliar Actors, New Audiences by Pirkko Koski

- Corruption, capitalism, class, memory and the staging of difficult pasts: Barcelona theatre and the summer of 2018 by Maria Delgado

- Reframing past and present: Madrid theatre 2018 by Maria Delgado

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018