My first article in this journal (European Stages, Vol. 11, June 2018) dealt with productions inspired by Trump’s election and the resultant upset of the political landscape. The present article will deal with productions with diverse theatrical explorations where identity is the dramatic core problem. Of course, the problem of identity, and its definitions in terms of personal, social, and political dimensions, is the essential driving force of drama – the very concept of identity harbors various conflicts: between the notion of self and other, between sameness and change, between inclusion and exclusion. Actors in America are typically asked two basic questions during rehearsal: “What do you want? And what / who is your obstacle?” These questions imply two identities in conflict. While American dramaturgy traditionally has explored this conundrum mostly on a psychological level, German dramaturgy has focused more intensely on a social and a political level.

The Deutsches Theater Berlin gave the 2017/18 season the motto: “What Future?” Intendant Ulrich Khuon raises this question from the perspective of a present that is filled with the past in a nonlinear fashion. Three interrelated topics emerge: How we will live together in the future is predicated on how we live together now and on how we have internalized our past in personal, social, national, and international terms. How is technology changing the definitions of human and non-human, i.e. the virtual substitutes, and what does that mean in terms of our relationships? And a related question: what is the future of the body, i.e. the physical body of the human species, in an increasingly robotic world. While the question of future encompasses much, the dramatic tension between established norms and new circumstances rests on the fundamental question of identity in this state of flux. In addition to the American-inspired productions at the Deutsches Theater (DT) dealt with in my first article, two other productions at DT examined various potentialities of identity and the human condition: the classic, Nathan der Weise, and a new play, Versetzung.

Nathan der Weise [Nathan the Wise], Deutsches Theater

Nathan der Weise [Nathan the Wise] by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, under Andreas Kriegenburg’s direction from 2015, is an astounding rendering of this 18th century German classic. Designated by Lessing as “a dramatic poem,” it has been a fixture of German literary education (except during the Nazi period), and is celebrated for its message of religious tolerance. However, as director Kriegenburg develops the mise en scene, the traditionally central idea of tolerance in 18th century garb (or even in common 20th century update) fades under a most radical conceptualization, both visually and verbally. In a program note, dramaturg Juliane Koepp cites a line from the play – “This is the land of miracles”—as central to Lessing’s text and to “the radicality with which Lessing’s figures leap across the boundaries of tradition and religion.” Lessing wrote the play in 1779 after a major argument with Hamburg’s chief pastor Johan Melchior Goetze. In his Preface, Lessing writes: “I know of no place in Germany where this play could be performed at this time. But blessings and good luck to wherever it is first performed.” It premiered in Berlin in 1783, posthumously. The play reads indeed like a fairytale. Set in Jerusalem during the 12th century, the time of the Crusades and the reign of Sultan Saladin, the plot involves the Jewish merchant Nathan, his daughter Recha, her female companion the Christian Daya, a young Templar who saves Recha from her burning home (during the absence of her father who is on a business trip in Babylon), Sultan Saladin, his sister Sittah, and assorted ancillary characters. Lessing ends the play with several poetic strokes, dissolving the many misconceptions about the identities of Recha and the Templar, unmasking some misguided motivations of the characters, and revealing the murky past and tragic events that have embroiled Jews, Christians, and Muslims in this emblematic city. Religious and cultural distinctions are merged into the fundamental truth of common human biology, the power of reason, and all-encompassing love. The play is conceived as the ultimate allegory of Enlightenment ideals. However, what are we to make of this allegory in 2017/18, in a period of renewed personal and national identity crises, considering genocides past and present?

Nathan der Weise. Photo: Arno Declair.

Andreas Kriegenburg presents a spectral Genesis prelude with clay encrusted creatures rising from earth. Their whimpers and chirps gradually transform into sibilants and vowels; they explore their own naked encrusted bodies and find each other in innocent delight. In short, we are given a first vision of humanity unencumbered by language, customs, and rules. A twirling shapeless directionless mass, they gradually form groups, words, discover their nakedness, shame each other, find weapons, build structures with high walls that create boundaries, and finally cover themselves with pieces of cloth mingled with clay. This shorthand representation of emergent civilization is reminiscent, as the dramaturg tells us, of 2001: A Space Odyssey. To make sure the audience understands the intent, the program booklet quotes from Genesis in large letters: “Then the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life. Thus man became a living being.” The designs of Harald Thor (settings), Andrea Schraad (costumes), Cornelia Gloth (lighting), and Wolfgang Ritter and Martin Person (sound) fully support Kriegenburg’s stylistic radicalism and enable the ensemble of six nimble actors to drive the vision forward. The messages of the play are: a) specific identity becomes meaningless when humanity is stripped of any defining categories and b) defining categories of sameness and otherness become deadly weapons of fear. All specific accoutrements of culture are means of distinguishing and alienating one group from another, whether it is racial, ethnic, national, or gendered. In this production, only pieces of emblematic clothing, often ironically attached to a figure, define the actor/character as female or male, Jewish, Muslim, or Christian. The action itself is choreographed around very high every-shifting walls that can open and close, creating cramped interiors, fortress-like towers, or alleyways. Lessing’s “dramatic poem” is “a fairytale that follows the structural principle of comedy. “Humor as a statement against barbarism is one possibility to confront the overshadowing animosities. . . Director Andreas Kriegenburg conceives the story as an archaic comic–at the beginning is man, created from earth” (Program note).

Versetzung [Transfer], Deutsches Theater

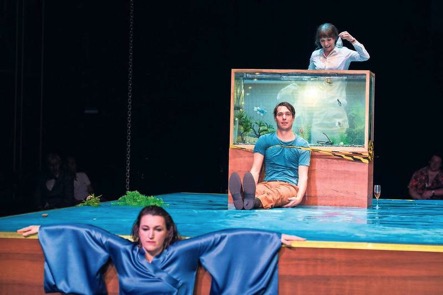

Versetzung [Transfer] was the last production I attended at DT during the 2017 fall season. It was the premiere of a new play by Thomas Melle, a writer who explores psychological identity crises triggered by pressures of performance and success (or what is considered success) in our modern performance-oriented society with its fixation on measurable accountability. The play was produced in DT’s Kammerspiele. Johanna Pfau designed a very handsome and aesthetic set on the expansive stage: a raised square platform with a sky blue surface, framed in wood and brass; upstage right on the platform, an aquarium on a wooden pedestal, and a movable wooden chest-type bench echoing the construction of the platform. Director Brit Bartkowiak was able to move the nine actors in interesting fluid configurations on and around the platform which became in turn a classroom, a teacher’s lounge, a private home, and the street, seamlessly shifting the psychic space without changing the outward appearance of the environment. The resultant unsettling sense of progressive inner uncertainty suits the central action of the main character’s descent into mental illness while the external circumstances, including the attitudes of his wife, students, parents, and his colleagues become ambiguous. The place is the same, the people look the same but do they really behave differently, or does his paranoia dictate their responses, is it his perception of their responses to him?

Thomas Melle and Brit Bartkowiak create in the course of two hours without intermission a maelstrom of shifting relationships and splintering reality. The plot is simple: Ronald Rupp is a successful teacher, intelligent and charismatic, beloved by his students and respected by his colleagues. He seems to have it all—professionally and privately: He is slated to become principal after Headmaster Schütz retires and his wife is expecting their first child. Then bipolar disorder, an illness that marked his past and that he had until now been able to suppress, resurfaces and threatens his future. He says: ”Everything changes, nothing remains the same. We are tipping figures. The background becomes foreground. The positions constantly move, even when everything seems to be fixed forever…be patient. Let it be. But let the others also be, those inside yourself. There may be glass but one sees each other. One can see each other.” He and the others feel his normal identity slipping, and so the others around him change as well—their customary identity is coming under doubt. Even as his pregnant wife, Kathleen, is contemplating her growing child, she wonders: “Am I defining myself only through you, or what. What is this construction, this life.” In this microcosm of a school, a psychic earthquake of one is shaking the fundamental self-understanding of the others, and all prior relationships lose their functional basis.

Versetzung [Transfer]. Photo: Deutches Theatre as credit.

Der Kaukasische Kreidekreis [The Caucasian Chalk Circle], Berliner Ensemble

Der Kaukasische Kreidekreis [The Caucasian Chalk Circle] by Bertolt Brecht was offered at the Berliner Ensemble (BE). The production, directed by Michael Thalheimer, premiered on September 23, 2017 on the big stage, a cavernous space whose height and horizontal expanse is impressive. It plays short of two hours without intermission. The stage remains empty, thus emphasizing the centrality of Narrative Performance. Brecht’s Epic Theatre relies on the non-illusionistic presentation of a story as a parable of a social problem. Brecht wrote The Caucasian Chalk Circle in the eleventh year of what he called “his exile” in America. The original play’s premise is the problem of the rightful relationship between the land and those who work the land—he sets this problem in a village in the Caucasus in 1944, that had been destroyed by the Germans. The story of the Chalk Circle is a parable in the Old Testament when Solomon determines by a test who should be the rightful mother of a child that was abandoned by the biological mother and saved by the maidservant. In Brecht’s version, a singer narrates an ancient Caucasian version of this story and the Caucasian villagers (from 1944) enact the parts. In BB’s work journal from 1944, notes about how to solve questions of characterization and structure abound; as with other plays written when he had no access to the stage, he struggled with the practicalities of working out the staging of scenes.

The BE production is a prime example of the central focus on playing the narrative. Only light, brilliantly designed by Ulrich Eh, and live music, composed by Bert Wrede and played on stage by Kai Brückner and Kalle Kalima, underscore the action. There is no “atmospheric” scenic imagery to tell us that the action takes place in a mythical Caucasus, and no use of masks to transport the play into legend. The costumes, designed by Nehle Balkhausen, tell us at once that place and people have been impoverished by the corruption of the ruling class and ravaged by war. Torn remnants of utilitarian clothing of various periods, some splattered with blood, are contrasted with the ridiculously incongruous gaudiness of the governing couple, Natella and Georgi Abashvili. Thus Thalheimer has created in the vast BE space, spotted with cold light, harsh music (electric guitar), and an ensemble of superb actors who play multiple parts, a totally integrated performance in the tradition of a Brecht Lehrstück. In his program essay, Dramaturg Bernd Stegemann points out the play’s dialectic model-like clarity, which is supported by Brecht’s first version of the play, that includes the Prologue set in a village in the Caucasus in 1947 (after its destruction by the Nazis) in which survivors attempt to consult about their future and their land. This production reinstates the Prologue, and the cut text tightens the central action around the figure of Grushe and the child she saves. It works like a station drama that follows Grushe’s actions and challenges them in the context of the villagers’ reactions towards her; every “station” or scene is set by the Singer who has come to the village without a troupe and engages the villagers in presenting his narrative. The Singer, played by the elegant Ingo Hülsman, in a smudged white silk suit, is a permanent presence downstage left where he observes and inserts himself into the action by announcing the next “station” in the narrative process, thus interrupting the plot flow (Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt) after which the actors visibly may change costumes to enter another character. (The only actors who do not play multiple roles are The Singer, Grushe Vakhnadze, and her fiancé, Simon Khakhava.)

Der Kaukasische Kreidekreis [The Caucasian Chalk Circle]. Photo: Matthias Horn.

The 1954 BE production, the last one directed by Brecht, was cast with 50 actors who were to portray 150 characters. Brecht resorted to masks to present the figures of the ruling classes who, in Brecht’s words, “have more rigid faces than the working [classes]. Those faces are representative. Special servants, especially lawyers who are bought by the rulers, also wear masks. In that case the rigidity reaches the simplest folk.” Thalheimer, obviously, interprets the question of class from our contemporary vantage point and does not mask any of the actors but has them play a mix of ruling and subject figures. Another Brecht quotation in the program notes: “When the house of a Great One breaks down, many of the Small are killed. Those who did not share the fortune of the Powerful share often in their misfortune.” A stunning choice of casting was the excellent actor Peter Luppa who appears first as the Governor Georgi Abashvili, his white face and blood-red lips distorted in a grimace of disdain, cruelty, and fear; he is swallowed up in his black fur coat, as he tries to flee from his killers. Later he appears as the vindictive mother of a half-dead son whom she pawns off on Grushe—one of the more farcical stations in Grushe’s journey. A third part was as a milk farmer. Peter Luppa is less than four feet tall but his presence on stage exudes an uncanny energy. Sina Martens plays his wife, Natella Abashvili, as a silly gaudy woman who manages to escape, leaving her child on the ground. Grushe takes it up with fearful reluctance, pretending that he is her own, thus saving the child from certain death. Miss Martens later plays a simple farm woman with some of the common unsympathetic streaks among people under threat. Nico Holonics portrays Simon Khakhava, Grushe’s first love (the two of them innocently playing at love with each other), who, as he undergoes the brutalization of soldiering, is lost to Grushe and to himself. Finally, the figure of Azdak, one of the most memorable scoundrels of Brecht’s creation, played by Tilo Nest, is a fantastic piece of staging in Thalheimer’s direction. He is played as the ultimate clown, a poor drunk, a thief, but as possessor of all these social ills, his judgment is based on the raw recognition of human nature. He declares Grushe as the rightful mother, even though, according to the letter of the law, she is a thief; yet, she saved a human life despite her fear and not from goodness (in the Christian sense). He presides over the court—and he plays all the parts– on an upside down bucket, wearing a Cossack wig that looks like a black mop on his head, dressed in nothing but dirty blood-splattered long-johns, on his naked stomach the tattoo of a cross, like an ironic comment. He delivers his sentence with excruciating exactitude—to his and everyone else’s exhaustion. Tilo Nest gives an absolutely virtuoso tour de force. The Production does not shy away from graphic images of horrendous violence– Grushe’s rape, for example—which would be part of the village’s real-life war experiences. The final image is exhausted Grushe, alone, lying sideways on Azdak’s upside down bucket “dais,” a circle of blood on the ground, hugging the child close to her heart. Justice has been served in favor of the one who preserved Life. However, in contrast to Brecht’s presumption of a useful social resolution, Thalheimer’s violent version implies that Grushe’s courageous deed is a solitary act while the rest of society is no closer to empathic human solidarity.

Returning to Reims, Schaubühne

Returning to Reims, after Didier Eribon, in a version by the Schaubühne, directed by Thomas Ostermeier. This production came to St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn in spring 2018. It had premiered originally at the Manchester International Festival on July 8, 2017 as a co-production of the Schaubühne, HOME Manchester, and Theatre de la Ville Paris. The first performance in Berlin was on September 24, 2017; it is part of the Schaubühne repertoire and is performed alternately in German and in English. I saw the English version in Berlin and in Brooklyn.

The text is based on two separate narratives. The first is Didier Eribon’s 2009 book, Retour a Reims which relates his visit to his home in a working class neighborhood of Reims after a long absence. He meets his recently widowed mother—he had been estranged from his father for years and did not attend his funeral—who resurrects old photographs from his childhood. For Eribon, born in 1953, the visit becomes a confrontation with his past and his identity in the place with visibly changed social and political conditions and his own social upward mobility as university professor, as well as his (now) acknowledged homosexuality. Eribon’s text is a philosophical meditation about the shifting narrative of social realities, represented by class and identity.

Returning to Reims. Photo: Arno Declair.

The second source is a narrative about Willi Hoss, the father of Nina Hoss, the actress who is the central performer in the Schaubühne staging. Willi Hoss, born in 1927 into a peasant family, studied Communism in the late 40s at the Party Academy of the SED [the Socialist Unity Party of Germany] in Kleinmachnow, a suburb of Berlin. He was one of five “West Germans” in the course, who came from what would become in 1949 the Federal Republic of Germany. The Party Academy was in the Soviet sector that would become the German Democratic Republic (in 1949) with the SED as the ruling party. Although the Cold War between East and West was beginning to intensify, movement between the Western and Eastern sectors was still relatively unrestricted. However, as a West German he was given a code name in order not to be subjected to any repressive measures when he returned as a qualified Party member. ”I was called Willi Heller…it felt like second nature to me to be Willi Heller. The Nazi era was not long past and legalities were, for us, rather relative: the law was something you couldn’t trust.” (Willi Hoss describes his experiences at the Party Academy in a 2004 publication, part of which is included in the Schaubühne program booklet.)

Both, the Eribon and the Hoss narratives center on the question of identity, as it is experienced over time personally, socially, culturally, and politically. The multifarious aspect of identity in terms of categories of definition has become a topic of strenuous political debate, as identity politics has come to dominate political discourse which has led, in turn, to reactive repression, random violence, and even genocide. The more the world has technologically turned global, the more “communities” (as social media designates interest groups) see themselves and others stringently separate. So, how does the production of Returning to Reims address the topic of identity theatrically? It is certainly not a conventional work of drama—there is no dramatic conflict, there are no characters or figures that play a part in a plot. It is theatrical without being a spectacle. However, stories are being told on stage by the actors.

Returning to Reims. Photo: Arno Declair.

At the Schaubühne, the production is staged on the Globe Stage. The audience is seated in a semi-circular formation around the stage that has been converted into a sound studio, designed by Nina Wetzel and associate designer Doreen Back. As the audience enters, some technicians in the sound booth behind glass are setting up for the next recording session. They banter, get coffee, banter some more, and then suddenly all the lights go out. There is a lengthy period in total darkness. Then a door is heard opening, somebody enters and switches on the light. And there is Nina Hoss wondering if anybody is around, as she takes off her coat and settles on the high chair by a desk and a microphone in the middle of the stage. She opens a script and quietly begins to read, when suddenly the other two actors re-enter to begin the work of taping the reading. One is the director of the project, Bush Moukarzel, and the other the technician, Ali Gadema. Nina Hoss reads from the text while a video is projected on the back wall that shows Eribon in profile as he rides the TGV train to Reims. The stage action develops and intensifies, as Nina Hoss raises structural questions, and the Director justifies his choices of imagery for the text—their argument becomes theoretical (and funny). The technician bursts out of the sound booth at one point to remind them of time and the fact that their studio rental is limited. In frustration about their bourgeois theoretical arguments about the nature of working class identity, he flops on the sofa, seemingly ignoring them. The irony is perfect: here is the real working class man being utterly ignored by the intellectual and the artist in their argument about defining the working class. Meanwhile Eribon photos of the Reims working class neighborhood are projected on the background. The performance rises to a climax when Ali Gadema suddenly leaps up from the sofa and launches into a capella rap and break-dance in genuine Bronx style genius with Arab sentiments, thus instantly eclipsing the intellectual banter of Bush Moukarzel and Nina Hoss with the pure raucous energy of his physical poetry. (Ali Gadema got spontaneous applause in Berlin and in Brooklyn.) The ironic comment on stage is inescapable—it is about race and class identity—just as Eribon’s personal narrative underscored by the film is about class and sexual identity. Both are theatrically presented as simultaneously hard-edged and fluid—and therein sits the dramatic conflict, experienced by the performers on stage as a present social dichotomy while Eribon on the screen goes through internal soul searching—trying to find an authentic connection between his past and his present identity.

The performance resembles a simple studio taping session/rehearsal, but the actual dramaturgy and technical coordination is quite complex. Thomas Ostermeier and Sebastien Dupouey directed the film in which Didier Eribon is followed to his home in Reims; we also see archival footage of some of the May ’68 events as well as private photographs and his dialogue with his mother about these photographs. Nina Hoss is impressive as she reads the Eribon text in her quiet unassuming way—she is simple, “unactorly” but with a beautiful voice and clear diction. In the last part of the performance, she presents a home video (projected via her smartphone on the background for all to see) of her father Willi Hoss, as both of them travel deep into the Amazon territory. He is shown working with a native tribe teaching them how to do crop rotation. He is accepted and initiated into the tribe as an honorary member thus upending the notion of identity as a fixed norm. The technical facility with which we now can resurrect memory as past actuality with an instant live image—as a readymade—becomes an interesting phenomenon when presented simultaneously on stage with the live actor: past and present, absent and present coexist in visible/audible interaction. “Returning to Reims” questions the viability of a stable identity when categories of definition are at best expedient and at worst destructive to the human enterprise, personally and socially.

ZEPPELIN, Schaubühne

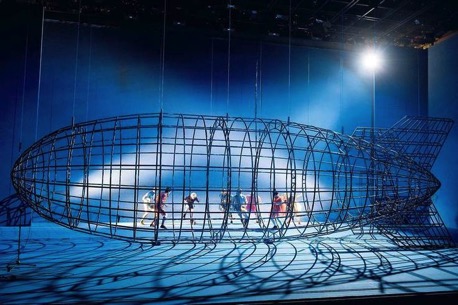

ZEPPELIN, was freely adapted by Herbert Fritsch from texts by Ödon von Horvath at the Schaubühne with direction and set design by Herbert Fritsch with costumes by Victoria Behr. Music: Ingo Günther. The dramaturgy was by Bettina Ehrlich and lighting byTorsten König. The ensemble was composed of Florian Anderer, Jule Böwe, Werner Eng, Ingo Günther, Bastian Reiber, Ruth Rosenfeld, Carol Schuler, Alina Stiegler, Axel Wandthke.

Ödön von Horvath (1901-1938), contemporary of Bertolt Brecht and frequently grouped with German writers and painters of the Neue Sachlichkeit category, was a prolific novelist, short story writer, essayist, and playwright. While he had theatre and publication success in Germany and Austria in the 20s and early 30s, the Nazi regime made life and work impossible for him, and he became a refugee like many of his friends. He died in Paris when he was struck by a tree branch during a thunderstorm as he was on his way to meet Hollywood director, Robert Siodmak. Horvath’s work was rediscovered in the late 60s, and his plays became some of the most produced in German and Austrian theaters during the 70s and 80s. His plays “Tales from the Vienna Woods” and “Don Juan returns from War” ” in Christopher Hampton’s translations found receptive audiences in England and the US. Horvath’s quirky wit is reminiscent in its absurd logic of the Bavarian comic Karl Valentin. His language and visual imagination are rooted in the Bavarian/Viennese folk idioms, but his collection of colorful characters live in the dismal post-World War I working class milieu. I was curious what Herbert Fritsch would do with an assemblage of Horvath texts under the curious title, Zeppelin.

Zeppelin. Photo: Thomas Aurin.

Fritsch derived the title of his production from the opening scene of Kasimir und Karoline, set at the Octoberfest with its freak shows and game booths. A Zeppelin floats above and Karoline sees it as a heavenly vision. Her companion Kasimir abreacts his frustration of having been laid off by playing “Haut’s den Lukas”—the German version of Whack-a-Mole; he pours cold water on Karoline’s romantic view by harshly commenting that most likely a few select “high rollers” in that tiny cabin are looking down at the multitude below that has barely enough to eat. Horvath with a few strokes sets the psychosocial context. Horvath’s ironic motto for the play: “And love will never end.”

Herbert Fritsch built on the wide Schaubühne stage a huge Zeppelin skeleton that becomes the playground for the colorfully costumed ensemble of actors as they move in, on, and around the Zeppelin structure, displaying incredible acrobatic feats while throwing an assortment of Horvath phrases at each other and at the audience without any apparent logic. It is a feast for the eye. The Horvath fragments are drawn from his plays and his prose work but alienated from their original context. Horvath, at one point, had said that people do not manipulate language but that language manipulates people; he meant that the slogans and formulaic emotionality of political and commercial propaganda have replaced authentic speech which is rooted in personal feelings and thoughts. Apparently Fritsch had access to Horvath texts, sketches and drafts that had not been included in previous publications. However, if one is familiar with Horvath’s diverse writings, one discovers theatrical moments suggestive of his proclivities for circus-like situations, freaks and outliers, and ironic absurdities.

A large young audience came to see the performance that I attended in November 2017. The Zeppelin is first hidden from view by a huge scrim like a blue sky that closes off the entire stage. Suddenly eight clownish figures tumble in, take down the scrim, and run off. The huge Zeppelin skeleton hovers on the stage. A Musician (Ingo Günther) in a black coat and top hat walks to a console on stage right and revs up the electronic music –it sounds as if bones are playing on the skeleton. The action begins. A soccer ball rolls on stage from stage right, followed after a couple of beats by a boy running after it; they disappear stage left, only to reappear reversing the action. The Zeppelin lifts slightly off the floor, and the rest of the ensemble enters the stage and climbs onto and into the Zeppelin structure. The soccer ball action refers to “The Legend of the Football Field,” one of Horvath’s short stories from the collection Sport Fairytales, in which a poor young boy attends all the games secretly sitting on the cold wet grass under the bleachers, shivering as winter approaches; he catches his death and flies with an angel to the eternal soccer field among the stars. Horvath’s characters seem to skirt, court, or succumb to death, and this proximity to death produces a melancholy streak mingled with their profound longing for a better world in which their dreams could unfold—that is the world of Horvath.

Zeppelin. Photo: Thomas Aurin.

Herbert Fritsch pays a brilliant homage to Horvath by his choice of the Zeppelin skeleton as a visual metaphor. It challenges the actor/figure physically to be airborne, to ascend and descend, to “hang on,” to delight in the sheer ecstasy of “being on top,” before being ignominiously displaced, and finding oneself “grounded,”—all of which is a common quality of Horvath characters. Horvath himself was a man between worlds, belonging to no nation. In an autobiographical sketch, he says: “You are asking me, about my home [Heimat]. I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Bratislava [Pressburg], Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport—but: “Heimat”? Don’t know. I am a typical old-Austrian-Hungarian mixture: Magyar, Croatian, German, Czech—my name is Magyar, my mother tongue is German. I speak German best and write only in German now, thus my cultural milieu is German, I belong to German people. However: the term “Fatherland” has been nationalistically falsified and, as such, is foreign to me. My fatherland is the common folk. So, as I said: I have no home; of course, I don’t suffer because of that but I delight in my homelessness because it frees me from an unnecessary sentimentality.” Herbert Fritsch chose an author who defied nationalistic notions at the cost of livelihood and life. With a powerful metaphor and a brilliant ensemble of actors, Fritsch created a stunning celebration of freedom from constraints while precariously balancing between heaven and earth.

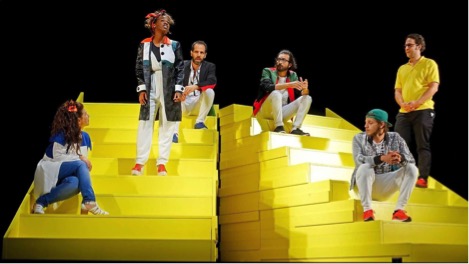

The Situation, The Gorki

The Situation has been since 2015 offered at The Gorki, a theatre located in the center of Berlin near Humboldt University. With the most inclusive artistic team and acting ensemble in terms of cultural and ethnic diversity, including an “Exile Ensemble,” the theatre produces works, often as ensemble collaborations, that deal with radical political and social issues of present-day Berlin but with a global view. Berlin has become a dynamic crossroads of the young global community, and The Gorki has been able to engage the energy of this phenomenon.

Israeli Yael Ronen, the resident director at The Gorki devised “The Situation” with an ensemble of six actors: Ayham Majid Agha (Hamoudi), Karim Daoud (Karim), Maryam Abu Khaled (Laila), Orit Nahmas (Noa), and Yousef Sweid (Amir). (The actors Agha, Khaled, and Daoud are members of the special Gorki Exil Ensemble.) The actor/characters have come to Berlin from Syria, the Palestinian Westbank, and Israel. In order to make a new life, they have to learn German and be “acculturated” to German social customs. They find themselves thrown together in a German language class. This is the actual on-stage situation but The Situation refers not only to the Palestinian-Israeli situation but more deeply to the various causes of displacement and the subsequent uncertainties in redefining oneself under the pressure of one’s “situation,” where the political, social, and personal dimensions are a volatile mix. The performance, set in a classroom with several steep risers, designed by Tal Shacham, allows for internal power plays that can lead to humorous exchanges and taunts as well as to heightened tensions, especially when Palestinian and Israeli or inter-Arab conflicts surface. The “German” teacher, played by Dimitrij Schaad, reveals himself in the end as an immigrant from Russia, being the descendent of Volga Germans whom Stalin had forcibly displaced to Siberia—the presumed native German teacher is himself the product of multiple migrations. The actors commit to their personal narratives passionately and their confrontations give the performance a feel of documentary authenticity. Their painful memories of warfare, life in a refugee camp, being scrutinized by Israeli security forces, and loss of life through terrorism and bombings in the region show the brutalization of all populations.

Situation. Photo: DPA.

The Gorki is an important enterprise in that it confronts on a very basic human level the problems of inclusion and exclusion as real experiences. The theatre is a focal meeting place where actors from different cultural and migrant backgrounds can work together and present their collaborations to an audience, both German and immigrant, thus facilitating at least the possibility of a more differentiated understanding. The telling of stories can have miraculous effects on human capacity for empathy, certainly more than statistics and abstracts.

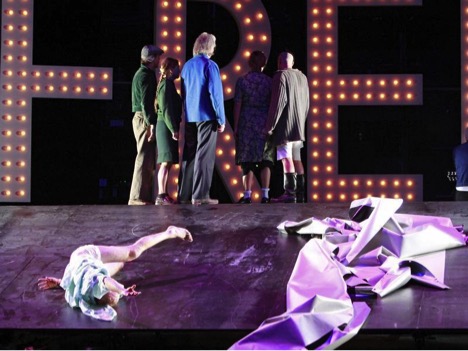

Jeder Stirbt für Sich Allein [Each Dies Alone], The Habimah (Tel Aviv) at The Gorki

Jeder Stirbt für Sich Allein [Each Dies Alone] after a novel by Hans Fallada, was presented by The Habimah, Tel Aviv, at The Gorki. As part of the ID Festival, this special guest production was a remarkable event. Adapted for the stage by Shahar Pinkas and directed by Ilan Ronen, the Habimah presented a dramatic version of Fallada’s novel based on the tragic story of Elise and Otto Hampel’s passive resistance against the Nazi regime during WWII. For an Israeli theatre company to present a German narrative about WWII and Nazi resistance in Hebrew in Berlin seemed to me an astounding event. The performance was stunning in its powerfully evocative yet restrained style. In 2017, The Habimah, the national theatre of Israel, celebrated the 100th anniversary of its founding in Moscow. It left Russia in 1926 and settled in Berlin until 1931 when it went on to Palestine. Hans Fallada wrote the novel in October-November 1946 and died a few months later; it is known in Michael Hoffmann’s English translation as Alone in Berlin–it was made recently into a film by that title. The novel is set during World War II in working class Berlin. The narrative centers on a couple, the Quangels, whose son was killed on the front; they make a solitary moral decision to call for resistance against the Nazis and their war—they distribute postcards around Berlin telling people not to support the war efforts. The Gestapo finally catches and executes them.

Jeder Stirbt für Sich Allein [Each Dies Alone]. Photo: Maxim Gorki Theatre Berlin.

Berlin is a city with a rich theatre tradition and during fall 2017, exciting diverse offerings were presented at its most distinguished houses, the DT, the BE, the Schaubühne, and Volksbühne am Rosa Luxemburg Platz—the latter has survived as a “House” and is presenting a 2018/19 season even though Chris Dercon was relieved of his directorship under controversial circumstances. Classic plays are re-visited with a sharp view to contemporary conditions and politics. German dramaturgical decisions about a theatre season are made in present-day Berlin with consideration of its increasingly international population and global position. The generosity of city, state, and federal cultural funds cannot be underestimated in the support of these institutions. Commercial theatre exists and thrives as well. I attended one production at the Renaissance Theatre, a bijoux, that survived WWII bombings. It was a delightful superbly acted production by the St. Pauli Theater, Hamburg. Hinter der Fassade [Behind the Façade or The Flipside of the Coin] by French playwright, Florian Zeller, was a comedy about upwardly mobile middle young people who hide their real emotions and motivations—i.e. real Identity.

Beate Hein Bennett, Ph.D. Comp. Lit., has worked as a teacher, translator, and freelance dramaturg. Born and raised in Germany and trained in all aspects of theatre arts, she has a high respect for the art in all its complexity from front to backstage, from spoken language to the language of the body. Her latest involvement has been as dramaturg for the New Yiddish Rep/Castillo Theatre premiere production in Yiddish of Waiting for Godot in New York. A theatrical highlight was as translator and dramaturg for The Living Theatre production of Else Lasker-Schüler’s IANDI on Avenue C. She is currently translating Judith Malina’s book The Piscator Notebook (Routledge, 2012) into German.

European Stages, vol. 12, no. 1 (Fall 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Joanna Gurin, Managing Editor

Maria Litvan, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 (Part II) by Beate Hein Bennett

- Report from Berlin (June 2018) by Marvin Carlson

- Othello, Shakespeare’s New Globe by Neil Forsyth

- Resistance Through Feminist Dramaturgy: No Way Out by Flight of the Escales by Meral Hermanci

- 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe by Anna Jennings

- The Avignon Arts Festival 2018 (July 6 – 24): Intolerance, Cruelty and Bravery by Philippa Wehle

- Le Triomphe de l’Amour : Les Bouffes-du-Nord, Paris, June 15—July 13, 2018 by Joan Templeton

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2018 of Brussels (Belgium) by Manuel García Martínez

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Contemporary Nordic Performance at the 2018 Arctic Arts Festival by Andrew Friedman

- A Piece of Pain, Joy and Hope: The 2018 International Ibsen Festival by Eylem Ejder

- The 2018 Ingmar Bergman International Theater Festival by Stan Schwartz

- A Conversation With Eirik Stubø by Stan Schwartz

- The Estonian Theatre Festival, Tartu 2018: A ‘Tale of the Century’ by Dr. Mischa Twitchin

- BITEF 52, World Without Us: Fascism, Democracy and Difficult Futures by Bryce Lease

- Unfamiliar Actors, New Audiences by Pirkko Koski

- Corruption, capitalism, class, memory and the staging of difficult pasts: Barcelona theatre and the summer of 2018 by Maria Delgado

- Reframing past and present: Madrid theatre 2018 by Maria Delgado

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2018