Although documentary theatre had not been fully absent from Hungarian stages before 2007, it was only in that year that a definitive trend of this genre started to take shape. It was then that the prestigious Katona József Theatre put on a series of performances celebrating both its thirty year history and the most prominent people in Hungarian theatre history.

PanoDrama, the first Hungarian documentary theatre group, was founded in the same year by the dramaturg Anna Lengyel (famous for her previous work with Krétakör/Chalk Circle). Since then, this group has staged performances on issues such as the race-motivated killing of Romani people, educational inequality, and minority rights. In most of their performances PanoDrama uses the verbatim method. Their last performance pays hommage to Milán Rózsa, a Hungarian gay rights activist who fought for many political issues and committed suicide in 2014. The director of the play was Andrea Pass; this was the second time that she worked with PanoDrama.

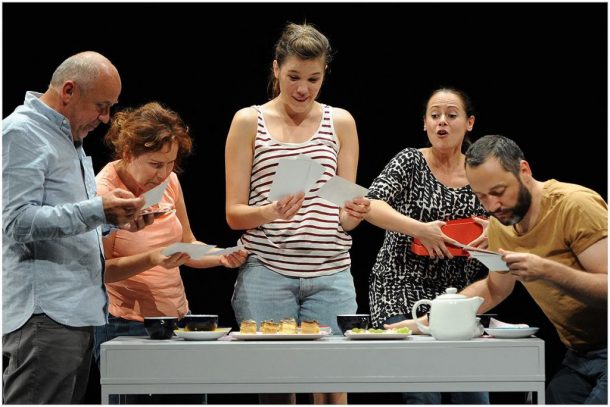

PanoDrama’s Don’t wait for a miracle, make it happen!. Photo Gyorgy Jokuti.

The title Don’t wait for a miracle, make it happen! – in memoriam Milán Rózsa provides in itself a key to the play’s dramaturgy. The performance is not only about Milán Rózsa’s courageous life but also the lives of Hungarian activists and their manifold issues. In this collage-like play only about half of the scenes are related to Rózsa (script: Judit Garai, Anna Hárs, Anna Merényi, Andrea Pass; conception and dramaturgy: Judit Garai, Anna Hárs, Anna Merényi).

These scenes show Milán Rózsa as a son, a friend and a fellow activist. The production refuses to mythologize him and the stories concerning Rózsa are not entirely positive by any means. People not only knew him from different situations (family, workplace, protests), but also his personality was ambiguous. Three of the scenes are a reconstruction of a meeting with his mother: one at the beginning, one in the middle, and one at the end of the play. The actors present at this meeting play characters other than themselves. This theatricalized, self-reflexive component highlights the process by which the play was made. The stories and the situation (in which trivia and tragedy mingle) are at once touching and cruel, as are those parts where fellow activists speak about their personal relationships with Rózsa. The most sensitive topics concern his depression, suicide attempts, and periodical self-harming.

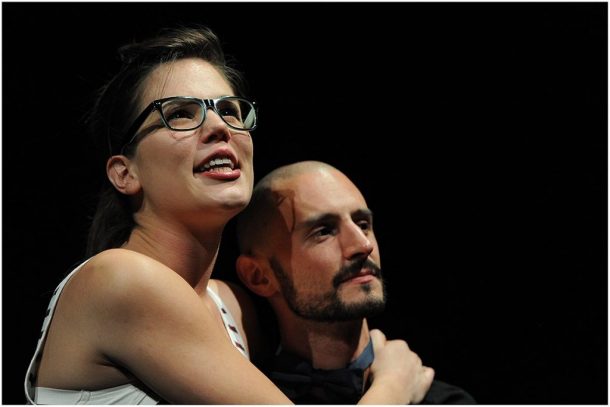

PanoDrama’s Don’t wait for a miracle, make it happen!. Photo Gyorgy Jokuti.

The scenes in which both Hungarian public life and the activists are depicted are not in chronological order. The scenes move back and forth over time, and the actors incorporate a wide variety of poses (sitting on the ground or behind a table, lying on a beanbag, facing the audience) so as to avoid the problem of “talking heads.” These scenes paint a picture of the erosion of democracy in Hungary from 2010 to 2017. Multimedia is not used in the performance (only dates and short description are presented on screens), and even the most iconic and notorious events are simply re-enacted theatrically, placing the records and photos in a new medium. The emblematic events of the last six years are vividly replayed but remain alienated, allowing us to see them in a new light.

The performance as a whole is a contemporary interpretation of “the personal is political” slogan. In the play we are presented with not just the personal life of Milán Rózsa (including his political acts) but also the wider societal and political contexts of his deeds.

The actors (Bianka Ballér, Zoltán Bezrerédi, Éva Botos, Tamás Ivanics, Tamás Ördög, Krisztina Urbanovits) play multiple roles. Cross-gender and cross-age casting is a device used in this performance as in other previous preformances of PanoDrama. At times, this makes the audience laugh and it also serves as a constant reminder that we are in the theatre—what we see is a shaped and edited representation of “reality.” In one of the most moving scenes, the youngest actors (Bianka Ballér and Tamás Ivanics) play the oldest characters (Imre Mécs, martyr of the 1956 revolution, is around 80, while his wife, radio dramaturg Fruzsina Magyar is around 60) who speak about the responsibility they feel for the younger generation.

PanoDrama’s Don’t wait for a miracle, make it happen!. Photo Gyorgy Jokuti.

The finale of the play is remarkable for its courageous stance. One of the actors asks the audience if there is any form of disobedience that doesn’t end in suffering. While we are pondering a possible answer, somebody begins to speak from the audience who is none other than Anna Lengyel, the artistic director of PanoDrama. She suggests not paying taxes, but acknowledges that there would be a limit to her commitment—for instance, not if it meant becoming homeless (which would be a direct consequence of not paying taxes in Hungary). This makes the actors’ last lines (which are spoken out of character à la Brecht) all the more validating: they warn us that an excessive burden is being placed on the shoulders of a handful of activists and that things could be so much better if only we could share our responsibilities.

In 2017, another kind of documentary theatre began to emerge in Hungary. Named “post-fact documentary theatre” by its creators, it is distinct from the verbatim method used by PanoDrama and others. An example of it is Hungarian Acacia authored and directed by Kristóf Kelemen (dramaturg, director) and Bence György Pálinkás (artist). The performance uses the cultural history of the acacia tree to question current concepts of nationalism. It is worth noting that the Hungarian government has been hostile to refugees since the first wave of migration in 2014, and its 2018 election strategy was, in part, predicated on xenophobia.

Kristóf Kelemen and Bence Gyorgy Palinkas’s Hungarian Acacia. Photo: Krizstina Csanyi.

Though originating from North America, the acacia tree has been part of the everyday life of Hungarian people ever since the 18th century, to the extent that many think of it as a native species. There is another reason why the acacia has a special place in recent Hungarian history. While the (now) ruling party was still in opposition, it considered the acacia as an invasive plant that had to be eliminated in accordance with EU law. Yet in 2014, they began fighting for it to be categorized as a Hungaricum (an object of national importance to Hungarian culture and history). There were a lot of symbolic gestures concerning these two opposing standpoints, and the sudden policy shift serves as a good example of the opportunism of contemporary Hungarian politics.

This historical and cultural potpourri is presented in the form of short newsreels, montages and lecture-like presentations. The performers (Angéla Eke, Katalin Homonnai, Kristóf Kelemen, Márton Kristóf, Bence György Pálinkás) display the mannerisms of a popular arts presenter (which highlights the theatricality of everyday life) but from time to time they use other kinds of performance genres and acting methods as well: singing and dancing, poetry slam, deconstructing the actor’s presence by video screening, even scenes that use psychological realism. The background music (by Márton Kristóf) is also heterogeneous and patchwork-like.

The performance space is more than mere scenery, but also serves as an innovative installation. We see a slope with soil and real acacias; and, while the audience settles in, the performers can be seen gardening in their overalls. After the show we are invited to have a closer look at the slope and are informed that the soil arrived from the different regions of the country, and that these acacias, in fact, are different subspecies of the tree. Otherwise, the space is used in a traditional way (with us sitting in the dark and the play unfolding before us), the one exception being when we are handed small pieces of buttered bread with acacia honey and a drink made from acacia syrup.

The performance’s use of humor is its most important weapon. We watch a filmed episode in which the performers make a short trip to the Ópusztaszer Heritage Park, an open- air museum representing the history of Hungary, where in addition to the usual “step back in time” atmosphere, one can also come across artistic presentations of mythical stories whose themes are used as part of the Hungarian nationalist discourse. The performers argue that if the acacia is a Hungaricum, then it deserves its place in the Park. After permission is granted, an acacia tree is duly planted there. This shows the history of the nation as a discourse that is constructed and one that can be appropriated or remolded at any time. The performers’ inference is that refugees can become part of the body of the nation just as the acacia did—this is a radical thought, but the film’s focus on the funniest details of the trip makes the whole procedure appear ridiculous.

Kristóf Kelemen and Bence Gyorgy Palinkas’s Hungarian Acacia. Photo: Krizstina Csanyi.

In another scene (in which screening and performing merge) we see the performers going on an excursion to a hill, where illegal communist groups held meetings during the twenties and planted a tree on 1 May 1927. On arriving, the performers also plant an acacia there. Katalin Homonnai recites a lesser-known poem of Attila József (which uses the acacia as a metaphor for the proletariat) but in the next scene the projected videoclip hints at the discontinuity of the leftist intellectual and political tradition (we see a fun-fair—a constant element of May Days during the communist regime in Hungary—and hear an uncanny re-mixed version of the song Dubinushka).

The creators poke fun at both the right and left wing traditions by means of the creative reappropriation of history and the discourses surrounding the acacia. There is no definitive standpoint and everything can become a joke from one moment to another. In other film clips we see the performers “remix” history by sticking a cut out picture of an acacia to historically-themed photographs and also current political discourse by dubbing the on-screen politicians so that it appears they are self-critical of their former behavior, supporting refugees and respecting the political opposition.

These two instances of Hungarian documentary theatre use very different stage languages: PanoDrama relies solely on theatrical apparatus, has a clear ethical standpoint, and reflects the process of creation in the performance; while Hungarian Acacia relies heavily on screening and music, merges documentary elements with fiction, and makes a joke of everything. But both share a responsibility for ongoing events in Hungary and our common future as citizens of the country and the EU.

Gabriella Schuller, PhD (1975) lives and works in Budapest, Hungary. She is a member of Theatre and Film Studies Committee of Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the author of many articles on contemporary Hungarian theatre, the performative practices of the Hungarian neoavantgarde, visual studies and performance art. Her book Iconoclasts. The Diversion of the Gaze in the Post/Feminist Theatre and Performances (2006) deals with the questions of feminist approach to theatrical representation. Since 2016 she has been a researcher and archivist at Artpool Art Research Center, Hungary.

European Stages, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 by Beate Hein Bennett

- 2018 Berliner Theatertreffen by Steve Earnest

- Speaking Out by Joanna Ostrowska & Juliusz Tyszka

- Political Theatre Season 2016-2017 in Poland by Marianna Lis

- Hymn to Love in a Love-less World: Chorus of Women, Berlin 2017 by Krystyna Lipińska Illakowicz

- Wyspiański: From Wagner, Through Brecht, to Artaud? The Curse and The Wedding in Poland Today by Lauren Dubowski

- A Theatrical and Real Encounter with Zabel Yesayan: A Play by BGST by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson

- Motus and Me: In Appreciation of the Italian Theatre Group Motus by Tom Walker

- Actors without Directors: Setkání/Encounter Festival of Theatre Schools in Brno, Czech Republic, 17-21 April 2018 by Matti Linnavuori

- Ghosts, Demons and Journeys: Barcelona Theatre 2018 by Maria M. Delgado

- Two Samples of Documentary Theatre in Hungary by Gabriella Schuller

- Two East European Festivals by Steve Wilmer

- The Misted Stage: Eirik Stubø’s Stagings of Tragedy by Eylem Ejder

- Amadeus in London by Marvin Carlson

- Two Significant Losses

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016