Christoph Marthaler has made his career devising theatre pieces that amalgamate text, music, and movement to do heavy philosophical lifting with a wicked sense of humor. Through these he has succeeded in creating a unique theatrical language that is at once absurd and strange, yet often strikingly poetic. His theatrical inventions have garnered numerous prizes and are presented all over Europe.

While devising his own work is Marthaler’s strong suit, he has also directed some classics by Shakespeare and Büchner and some holy cows of the operatic repertoire, such as Beethoven’s Fidelio and Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde at the Bayreuth Festival. Wagner especially seems to have struck a chord (pun intended), since the musical framework for Mir nämeds uf öis is mostly Tannhäuser, an opera concerned with deadly sin (old-school sex), remorse, pilgrimage, the experience of total rejection, and finally redemption. Interestingly enough, it is not the pope who pardons Tannhäuser; instead, God himself grants his soul freedom after Tannhäuser’s saintly lover, Elisabeth, prays that her soul be taken on his behalf. A harsh religion and a God wanting human sacrifice grant her wish. “Hoch über aller Welt ist Gott, und sein Erbarmen ist kein Spott!” (“High above the world is God, and his grace is no joke!”). Succinctly put.

Mir nämeds uf öis is the first work Marthaler has created at the Schauspielhaus Zürich with its ensemble since he was unceremoniously let go as director of the same theatre thirteen years ago. Are there hard feelings? During his reign he had put Zürich firmly on the map for avant-garde theatre that yielded international acclaim, prizes, and regular appearances at the famous Berliner Theatertreffen. But the general audience in Zürich had been rattled and confused by his very specific style, and they’d let him know. This year Zürich awarded him the Zürich Art Prize. Are they friends again?

His most recent theatrical invention introduces nine big sinners of our world, meaning those committing sins of money and exploitation rather than the traditional sins of the flesh. They are all creators of “complex predicaments” that spell ruin not only for themselves but for many people, states, and the whole wide world. Such complex predicaments cannot be salvaged, the culprits never redeemed. So in an analogy to “Bad Banks,” the firm called “Mir nämeds uf öis—State 17” (We’ll take it on—State 17) functions as a “Bad State.” Upon payment it removes the clients via air/spacecraft to an unknown location, where their guilt is sucked from them and deposited. Absolution on an industrial scale: this is what the nine passengers desire. But will they receive it?

It seems unclear to everyone involved—the clients as well as the one gentleman handling the boarding procedure and delivering little lectures along the way (Bernhard Landau)—just how long the journey will last, and how exactly the procedure works. The participants are anonymous, the precise plan unspecified.

Bernhard Landau and Ensemble of Mir nämeds uf öis, by Christoph Marthaler and Ensemble at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf, T+T Fotografie.

After a big “Ho! He!” courtesy of Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer, suggesting wind and water, the vessel takes off with a jolt. “This is the most unpleasant takeoff I’ve ever been a part of. I feel extremely sick,” announces the petulant butcher turned priest (Jean-Pierre Cornu). Moreover, everyone should please keep a “courtesy distance,” and allow him to choose his spot, since he is very tall. Everyone quietly gives him space, agreeing with him. Nobody is feeling very well right now. They sit.

As the evening progresses the visuals in the bow of the ship (video: Andi A. Müller) move from images suggesting a flight over mountaintops to more space-like visions: the vessel seems to soar above Earth, leave its atmosphere, fly through space dust, planetary constellations, darkness.

Along for the ride is a singing hologram (Tora Augestad), which then turns flesh, performing for the group but soon leading them in chorus. The gamut of musical choices range from Bach to Debussy, with a joyous excursion to Elton John‘s “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word” and Ueli Jäggi crooning like Udo Jürgens in his heyday. German Schlager lives on.

Ueli Jäggi and Ensemble of Mir nämeds uf öis, by Christoph Marthaler and Ensemble at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf, T+T Fotografie.

The musical lodestar, however, is Richard Wagner. Mostly the apt Tannhäuser, as noted, but other Wagnerian operas are quoted as well: Die Walküre (Act 2, Scene 2), Das Rheingold (Scene 4), and the aforementioned “Ho! He!” chorus from Der fliegende Holländer (Act 3, Scene 1).

The physical language is Marthaler’s special brand of movement, which starts with seemingly ordinary gestures—a flick of the wrist or a tapping of the foot while seated—that first moves from one person to the next, like contagion, then grows into more individualized steps: the feet lift, gravity is suspended, the ensemble members lie on their chairs moving their arms and legs like underwater bugs. The effect is one of poetic helplessness. The formerly powerful figures are children again, releasing control. The evening is filled with such moments, where movement, even dance, develops out of nowhere, sometimes slowly, sometimes bursting forth.

Ensemble of Mir nämeds uf öis, by Christoph Marthaler and Ensemble at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf, T+T Fotografie.

Marthaler’s signature slowness—his characters used to take forever to complete a (usually mundane) task or a sentence—has sped up. Mir nämeds uf öis, like other of his later works, such as King Size, doesn’t exude depressive lethargy, as did Stunde Null. Might this be because they are less grounded in the unique tedium of provincial Switzerland, which Marthaler captured like no other? the troupe waiting lounge and the Star Trek tedium of provincial Switzerland, that Marthaler had captured in the Eightiesthey b

The passengers seek relief of their guilt. But is that really possible? Hints abound. A video display overhead tells them that while everyone wishes for a pill to solve the blues, there is no such thing, so “get up and move on.” Promises aside, all is still up to you. In the program we are told that the door to the vessel is sealed with cement. So is this an updated version of Stalin’s ghost ships, loaded with prisoners, dragged out to the North Sea, and abandoned?

While the motley crew is dancing along, a voice over the public-address system informs the passengers that they need to be mindful of a risk: since the “complex predicament” of each is so connected with the individual, the machine or cosmic force intended to suck it out may also suck the very person into oblivion. Nobody reacts to this, however. Had it been clear all along?

The ensemble—nine clients, their handler (Landau), two pianists (Bendix Dethleffsen and Stefan Wirth), and a singer (Augestad, the hologram made flesh)—are a unified force, the “Marthaler family” at home with his unique style of working. When rehearsals began, there was merely a theme and a set by Duri Bischoff, a cream-colored dream-child between a luxurious waiting lounge and the Star Trek terminal.

Over the span of seven weeks the troupe began the process with the music. They sourced the mostly classical material, broke it out of its mold, and made it work. It is fascinating to hear Wolfram’s “Abendstern” (Tannhäuser), sung in English, performed as a lounge song (Augestad). The deconstruction of classical material creates an intriguing friction—nobody is grounded in the culture anymore, memory builds a whole from pieces. Music is the prime tool to express emotional need, and all nine “sinners” have needs to express: the need to be heard, the pain of remorse, or of futility. They all have worked so hard to have so much—money, assets, power, sex—and now they have nothing, since nothing lasts. And who are they now? What is left? They have boarded the last ship, paid the fare, hoping that their indulgences will buy them salvation.

Mir nämeds uf öis doesn’t explore the characters in great depth. Each gets one monologue telling his/her story, but what sticks is not so much the relative banality of the content of that story but how it is told. A formerly happy-go-lucky shitstorm salesman (Raphael Clamer) rattles off English terms that are now part of the German language: uploading, downloading, chilling, banging, Skype. The chorus begins repeating them, but nobody masters the speed. The construction tycoon (Gottfried Breitfuss) tells his story of continuous fraud on contracts on a grandiose scale—”Bau verträgt sich nicht mit Heiligenscheinen” (“Construction and halos don’t mix”)—stating that his best decision was to marry his wife, although a turn of phrase exposes him as a wife beater. During all of this the others lie on the floor as in sleep, moaning as a chorus—sometimes affirming, sometimes in surprise, or admiration, or pain. The businesswoman as stewardess (Susanne-Marie Wrage) tells us the story about a Greek tycoon who had everything, including a secretary thirty-five years younger than he, whom he loved like his daughter, only worse.

Gottlieb Breitfuss, Susanne-Marie Wrage, and Ensemble of Mir nämeds uf öis, by Christoph Marthaler and Ensemble at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf, T+T Fotografie.

This is where Marthaler’s work lives: in little vignettes like these, breaking open the hypocrisy of human pretensions, moving seamlessly from spoken word into song, into chorus, at one point announcing over the loudspeaker a radical musical change from a soft, lyrical mood into Richard Strauss’s Alpensinfonie. Strauss, like Wagner, is of course an honorary Swiss composer; after all, global business aside, everyone is still very proudly Swiss. Be it the butcher turned priest, the con man turned hair dresser—they all live in Switzerland, not the world.

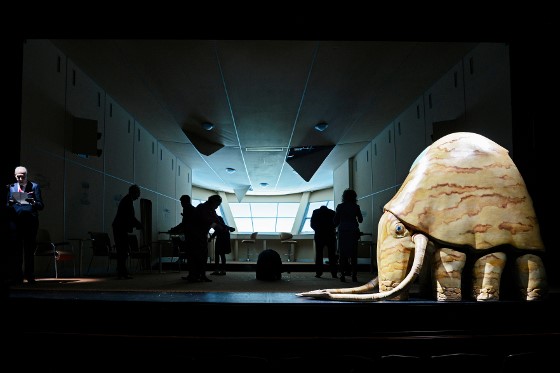

In the program there are no individual roles, even though in the piece characters are individually introduced. But it is the group that is key, and the importance of anonymity is stressed once they board the ship. Their journey is one of slow realization that they will not be saved; that not only will they be eradicated along with their “complex predicaments,” but also that the human race will follow soon as a consequence of their actions. The piece ends with a creature of the future appearing, looking very much like a small, friendly, primordial elephant-turtle in camo khaki. It gently opens and closes its one blue eye.

Bernhard Landau and Ensemble of Mir nämeds uf öis, by Christoph Marthaler and Ensemble at Schauspielhaus Zürich. Photo: Tanja Dorendorf, T+T Fotografie.

Is the universe a better, more peaceful place without us? “Naja,” says the handler (“Well . . .”).

Marthaler’s homecoming with Mir nämeds uf öis is a glorious success. The evening includes enough little jabs against the local society to soothe his soul, and the Zürich audience gladly took the opportunity to shower him with love. Now they can be friends again, no?

Katrin Hilbe is a director of opera and theatre working both in the US and in Europe. Her production of Julia Pascal’s St Joan won the award for “Best Direction and Adaptation” at the Dublin International Gay Theatre Festival, and her staging of Richard Strauss’s Salome for New Orleans Opera was awarded “Best Opera Production.” Select credits include Shooter (New York), Fägfüür (Liechtenstein, Zürich, Dornbirn), Fremd bin ich Eingezogen … (Konstanz), Die Schumann Sonate (Liechtenstein, Basel, Zürich), In Bed with Roy Cohn (New York), Breaking the Silence (Edinburgh), and Falstaff (Frankfurt). During 2007–2010 Katrin was the primary Assistant Director for Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen under the direction of Tankred Dorst at the Bayreuth Festival.

European Stages, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 by Beate Hein Bennett

- 2018 Berliner Theatertreffen by Steve Earnest

- Speaking Out by Joanna Ostrowska & Juliusz Tyszka

- Political Theatre Season 2016-2017 in Poland by Marianna Lis

- Hymn to Love in a Love-less World: Chorus of Women, Berlin 2017 by Krystyna Lipińska Illakowicz

- Wyspiański: From Wagner, Through Brecht, to Artaud? The Curse and The Wedding in Poland Today by Lauren Dubowski

- A Theatrical and Real Encounter with Zabel Yesayan: A Play by BGST by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson

- Motus and Me: In Appreciation of the Italian Theatre Group Motus by Tom Walker

- Actors without Directors: Setkání/Encounter Festival of Theatre Schools in Brno, Czech Republic, 17-21 April 2018 by Matti Linnavuori

- Ghosts, Demons and Journeys: Barcelona Theatre 2018 by Maria M. Delgado

- Two Samples of Documentary Theatre in Hungary by Gabriella Schuller

- Two East European Festivals by Steve Wilmer

- The Misted Stage: Eirik Stubø’s Stagings of Tragedy by Eylem Ejder

- Amadeus in London by Marvin Carlson

- Two Significant Losses

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016