The B*easts (2017) is a play about the consequences that ripple through and reshape the life of the eight-year-old Lila and her mother, Karen, when Lila gets breast implants. In erasing one letter, and replacing it with an asterisk, the textual equivalent, if you will, of a bleep, the title establishes “breasts” as a subject and word that must not draw attention to itself. It transmutes, because of this socially-imposed censorship, breasts into the word beasts, alluding to the primary subjects of the narrative—Lila and Karen—who are seen as beasts: the former for wanting to sexualize her body at such a young age, the latter for endorsing this act, thus “destroying” her child’s innocence. We never get to see the eponymous beasts on stage; it is a one-actor play featuring the BAFTA-award winning British actor, Monica Dolan, who also wrote the play. Dolan plays the role of Tessa, Karen’s therapist. She tells the audience the story of Karen and Lila. The play’s venue at the Fringe Theater Festival 2017 in Edinburgh was the Underbelly Cowgate. With its weathered appearance—in the background one hears the sound of water dripping— the Cowgate creates the perfect setting for the office of a court-appointed therapist whose office is a fairly humble space. The minimalist set design—a spot-lit couch and table—solidifies this impression. Tessa explicitly address her audience when she says, “Sorry, I’m doing that thing that old people do. Coming to you and starting talking about something in the middle of it and expecting you to know what I mean and then getting frustrated when you don’t” (all play quotes are from the 2017 edition published by Samuel French). In an interview, Dolan describes the performance as a shared experience between her and the audience.

Hoggarth, The B*easts. Photo: Allan.

Many reviews of the performance discuss the pertinent feminist questions that the play raises: who owns a woman’s body? why are breasts treated as sexual objects? The lens I adopt in my review, however, is the play’s treatment of how and why a child who deviates from the norm is labeled a monster—a beast—and the spectrum of ramifications that the application of such a label has on the child and her family, from social isolation to, in Lila’s case, abuse.

Lila, the play’s child-monster, is aware of women’s bodies from an early age: at the age of six, two years before she gets implants, she points, in the women’s magazines that Karen reads, to women dressed in bikinis and chants:“Want, want.” Karen at first assumes that a bikini is what Lila desires; until Lila points to a woman who wears nothing and Karen recognizes—but does not immediately acknowledge—that what Lila is after are breasts. While the thing Lila desires is an adult body, an adult state of being, her seeking of it and her gestures are childlike. Holding the magazines, too bulky for her small hands, at a tilt, she “paws” at the images, and when Karen takes the magazines away from Lila in an attempt to ignore her demand, Lila expresses her displeasure by throwing a tantrum (6). Details that juxtapose Lila’s desire with how she expresses her desire, reveal the complexity of Lila’s nature that refuses easy categories, for she is neither “only child” nor “only adult,” but rather, like an adolescent, an unnameable mix of the two states of being (though far from adolescence herself).

Similarly, when Lila is three years old she attempts, the audience is told, to draw the attention of her father’s friend: she wears her “plastic Dream Dazzler high heels and princess tutu and then she lifts her tutu and shows him her pants” and jumps on his lap (3).Her desire, which seems beyond her age, appears to be at odds—to the characters in the play—with her expression of affection towards her object of desire, which reflects her age.

The play’s narrator, Tessa, who is Karen’s psychologist, attempts to explain the reason for Lila’s desire: Lila is ignored by her father, who left his family when Lila was six. While Tessa’s description of the father-figure as Lila’s “blueprint for the opposite sex” is compelling, ascribing the father’s dispassion towards his offspring as the reason behind Lila’s desire for an older male figure, for a grownup woman’s body, and for breasts, it seems a distracting summation of Lila’s complexity that is in fact a quality endemic to her nature. Lila’s simultaneity—adultness, childness—I think, just is, a quality inherent to Lila’s being, a fact that, later in the play, Tessa corroborates: “Lila just wanted to be a big girl […] and that’s normal, it’s always been normal” (29). Lila is seen as “freakish…[and] in charge of her freakishness,” but she is, quite simply, “a female child that wants to be a woman,” and while environmental realities may have facilitated the expression of this simultaneity, they are not the reason for its existence (21, 25). This is Lila’s truth, and in acknowledging it, The B*easts initiates a critical dialogue: not all children are, as the saying goes, cut from the same cloth, and deviations from the “norm”—as defined by an adult imagination—is no more a sign of monstrosity than is Lila’s desire for breasts is a sign of the erasure (or absence) of her innocence.

To find merit in this argument one need look no further than the temporal nature of the socially-accepted definition of who is a “normal” child. In pre-Victorian times, children were generally seen as no more than cheap labor, and much of the sentimentality that has come to accumulate around the words “child” and “childhood” are later inventions that ascribe innocence to and turn “the child” into a being in need of adult protection. Tessa draws attention to this fairly recent but deeply-ingrained notion when she says: “Does it look as if the child isn’t inherently innocent and good? […] Something inside everyone balks at that […]. We can’t look at the child and say the child is to blame […]. That would ruin our notion of what innocence is” (26).

While associating these attributes (innocence, the need for adult protection) with a child does not, in and of itself, pose a problem, to reduce the child figure exclusively to these two attributes becomes problematic, for doing so turns children who—like Lila—don’t conform to the widely-circulated notions of innocence into “beasts.” If we see Lila as an “anomaly,” as Tessa says, “we won’t do anything about” the problems with the “bigger picture” (28).

Lewis W. Hine depicts the unromanticized treatment of children in 1908; here they are seen working in cigar factory in Tampa, Florida. Photo: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Tessa mentions other situations and social realities that, seen in this light, endorse—rather than create—Lila’s desires to appear physically “grown up” and facilitate its expression. When Lila turns seven, Karen throws a “Pampering Spa Diva Makeover Party…with non-alcoholic champagne reception where they give the girls elderflower in flutes and they can have massages and their make-up and nails done and they do a catwalk at the end on a red carpet with floor balloons…they’re designed for age four upward” (12, emphasis mine). It is at this party that Karen watches Lila and the other girls her age talking about women’s bodies: pointing, in magazines, at the ones they like. Further, Lila, the audience comes to know, wears padded bras when she is seven: a stopgap measure Karen comes with, a temporary stand-in, as it were, for the breasts that Lila wants. She wears makeup from the age of three, procured from ToysRUs, and also gets a cosmetic tan for which she is called tanorexic by a stranger on the street. This incident foretells the scathing criticism that Lila would later face for getting breast enhancement.

When Lila turns eight, Karen takes her to Brazil to get the breast implant surgery, the rationale behind the overseas surgery being that it’s more cost effective and less likely to evoke questions from medical practitioners. Once Lila returns to school, her altered body turns her from a classmate and a student to an object that must be feared and concealed. “The teachers were mainly in shock,” Tessa says and, “the first instinct of…a female teacher…was to take Lila out of the class, covering her…with one side of her coat like a streaker at a football stadium, and taking her to a small room to sit on her own […] with her breasts […] as if they were to be ashamed of” (17).

Whereas the act of concealing Lila with a cloth marks her body as an object of shame, the act of removal and isolation—with its obvious parallels to the detentions that follow when schoolchildren violate a code of conduct—subjects Lila’s personal choice to the same scrutiny as behaviors such as bullying. The teacher’s actions make Tessa wonder “how…we give older, less precipitously developing girls this message of shame [about their bodies] not in order to protect them […but] to externalize our own shame which we were given at some similar stage, in a similar way” (17).

Even as Lila is examined by the school nurse and doctor, the teachers who “field parents for whom the line between concerned, nosy, and hysterical was becoming increasingly blurred” decide that Karen, by consenting to the surgery, put Lila through physical and emotional abuse. Consequently, legal and academic forces unite to separate the two: Lila is sent to a care facility and Karen is taken into custody and placed, as Tessa observes, in an “enclosed facility that isn’t a prison” (26).

Once the media gets wind of the story and makes it public, reporters and readers alike begin “baying for the notion of childhood innocence,” Tessa says, and “the mother was vilified for sexualizing her child…for her cold-blooded murder of the ideal of the innocent child” (26).Yet, the public spectacle that these reports make of Lila’s story—her body—also serve another, more insidious purpose: “they…exploit a fascination with child sexuality whilst at the same time condemning it and ultimately blaming her mum,” so that, as a consequence, Lila is “taken from the gray area between public interest and institutionalized pedophilia and appropriated into a darker community” (20-21). The “darker community” referenced here is the Internet, for soon after Lila is taken to the care facility, she receives digital requests for selfies. Eventually, with the assistance of a care worker, a perpetrator finds his way to Lila and sexually abuses her. Indeed, as Tessa points out, the society that creates the rules for who is innocent and who a beast, is “the jungle out there” and they are the “reason, paradoxically, that we’ve got the odd teenager buying Botox” (29).

After separating parent from child the law requires Karen to meet a therapist, and Tessa comes in to fill this role. Time passes, and even as Lila turns twelve, a reversal of the operation is discussed, a surgery which, Tessa rightly states, goes against the course of adolescence “through which nature will soon require [Lila] to be a sexual being” (27); further, she asks, “where are we, ethically, enforcing a breast reduction operation on a child who does not want one?” (27).

In talking to her fictional audience—the show’s real audience—Tessa turns from therapist to storyteller, and like all powerful stories, it gets listeners to think and becomes an introspective experience for the storyteller: through the act of storytelling, Tessa works through a personal crisis. Over the course of the telephone conversations Tessa has—with her son and husband, Phil—as she tells Lila’s story, it becomes clear that Tessa is in the process of making a decision concerning her own body, specifically, her breasts. Diagnosed with breast cancer, she decides, over the course of telling the tale of Lila, that post-surgery, she does not want to have her breasts re-sculpted. Her initial uncertainty about the matter is evident in the way she broaches the subject in the early phone calls. She speaks haltingly, and after ending the calls she takes nervous drags on her e-cigarette or has a finger of whiskey. But as she concludes her narrative, she sounds certain about her decision. By finding her resolve through the telling of and reflecting on Lila’s experience, Tessa not only performs an act of resistance against a society in which a girl who makes such a choice is both violated and labeled a beast, she concurrently reveals her stance on Lila’s and Karen’s choices. The alignment between her act of bodily erasure, brought about by medical conditions, and Lila’s act of bodily enhancement, a cosmetic intervention, seem a little too neatly aligned, but this narrative choice, nevertheless, makes Tessa a more believable—by which I mean a more empathetic—narrator of the chaos in which Lila and Karen find themselves.

Further, the play’s point-of-view allows the narrative to present and comment upon that which has come to pass, a possibility that may have been more difficult to realize had Lila or Karen narrated the story immersing the audience in the chaos of their experiences. It is in hearing from Tessa—who, as Karen’s therapist, has both an in-depth understanding of the situation and the right degree of remove and expertise—that we receive both the how and the why of the events which allows us to question the implications of labeling a child who deviates from a tightly bound adult code of innocence a monster, and explore the possibility that a child’s reality may in fact be more complex than one might imagine.

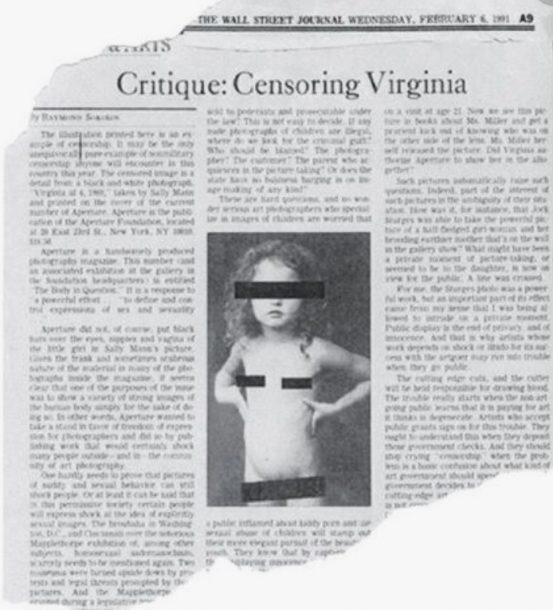

Like Karen, the photographer Sally Mann was criticized for eroticizing her children—of stripping them of their innocence—with the publication of Immediate Family (1992) in which her children appear partially clothed or naked in the wilderness surrounding the family farm in Virginia. A scathing critique of Mann’s work by Raymond Sokolov was accompanied by what Mann rightly calls—in her rebuttal to Soklov that appeared in The New York Times—a “disfigured” version of one of her pictures: in it black bands cross out parts of her daughter Virginia’s body, reducing her—and a complex childhood narrative—to an exhibit in a “child-pornography prosecution (“Sally Mann’s Exposure”. The New York Times Magazine. April 16, 2015. September 9, 2017).

“When we saw it,” Mann writes “It felt like a mutilation, not only of the image but also of Virginia herself […] it made her feel, for the first time, that there was something wrong not just with the pictures but with her body […] she wore her shorts and shirt into the bathtub” (2017).

Sally Mann’s censored photograph in the Wall Street Journal. Photo: The New York Times.

Dolan, The B*easts. Photo: Bush Theater.

Virginia’s censored photograph, when juxtaposed with The B*easts’ poster depicting a child whose face is pixilated, and Mann’s experience when juxtaposed with Karen’s, further underscore the realness and relevance of the troubling narrative of the play’s fictional account. Before labeling a child a beast, before blaming her mother for mutilating her innocence, one might want to question if ascribing such labels—which separate Lila from her mother and expose her to the abuse she is subjected to, which make Virginia believe there is something wrong with her body—might be the bigger acts of monstrosity, for they fail to make space for any degree of nuance in their understanding of innocence, and further, as Tessa points out, project and inculcate in the child an adult shame of the body. In the words of Mann: “The image of the child is especially subject to that kind of perceptual dislocation; children are not just the innocents that we expect them to be. They are also wise, angry, jaded, skeptical, mean, manipulative, brooding and devilishly deceitful. ‘Find me an uncomplicated child, Pyle,’ challenged the journalist Thomas Fowler in ‘The Quiet American,’ by Graham Greene, adding: ‘When we are young we are a jungle of complications. We simplify as we get older.’ But in a culture so deeply invested in a cult of childhood innocence, we are understandably reluctant to acknowledge these discordant aspects or, as I found out, even fictionalized depictions of them.”

Shastri Akella is a PhD candidate at the University of Massachusetts (Amherst), where he earned an MFA in writing. His thesis examines the intersection between migration and monster studies. His writing has been published or is forthcoming in World Literature Today, Guernica, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, and The Common, among other places.

European Stages, vol. 10, no. 1 (Fall 2017)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 2017 Avignon Festival: July 6 – 26, Witnessing Loss, Displacement, and Tears by Philippa Wehle

- A Reminder About Catharsis: Oedipus Rex by Rimas Tuminas, A Co-Production of the Vakhtangov Theatre and the National Theatre of Greece by Dmitry Trubochkin

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2017 in Brussels by Manuel Garcia Martinez

- A Female Psychodrama as Kitchen Sink Drama: Long Live Regina! in Budapest by Gabriella Schuller

- Madrid’s Theatre Takes Inspiration from the Greeks by Maria Delgado

- A (Self)Ironic Portrait of the Artist as a Present-Day Man by Maria Zărnescu

- Throw The Baby Away With the Bath Water?: Lila, The Child Monster of The B*easts by Shastri Akella

- Report from Switzerland by Marvin Carlson

- A Cruel Theatricality: An Essay on Kjersti Horn’s Staging of the Kaos er Nabo Til Gud (Chaos is the Neighbour of God) by Eylem Ejder

- Szabolcs Hajdu & the Theatre of Midlife Crisis: Self-Ironic Auto-Bio Aesthetics on Hungarian Stages by Herczog Noémi

- Love Will Tear Us Apart (Again): Katie Mitchell Directs Genet’s Maids by Tom Cornford

- 24th Edition of Sibiu International Theatre Festival: Spectacular and Memorable by Emiliya Ilieva

- Almagro International Theatre Festival: Blending the Local, the National and the International by Maria Delgado

- Jess Thom’s Not I & the Accessibility of Silence by Zoe Rose Kriegler-Wenk

- Theatertreffen 2017: Days of Loops and Fog by Lily Kelting

- War Remembered Onstage at Reims Stages Europe: Festival Report by Dominic Glynn

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016