The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2017, directed and curated by Christophe Slagmuylder, is an outstanding transdisciplinary arts festival, showcasing many new creations, often produced by the festival itself. Those creations, most of the time daring and often fascinating, question the traditional limits of the arts, and of the concept of theatrical productions. This year, among productions that combined different genres, many creations challenged the limits of perception and the usual hierarchy of the senses.

The special guest of the Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2017 was Tarek Atoui, an artist born in Lebanon and living in Paris. There were a few events that focused on his work: an exhibition, several public rehearsals, and four concerts. The exhibition presented some musical instruments designed specifically for people partially or totally deaf. The exhibition was guided and the audience admitted in very small groups. A deaf woman presented the instruments, invited the audience to try them briefly, and answered questions.

The surprisingly ingenious instruments allow people who are deaf or hard of hearing—as well as the visitors of the exhibition—to feel the vibrations produced by the instruments through their hands, sometimes by allowing them to touch the instruments’ stands which are made of wood or of other materials. Thus, the audience can feel the same things as the deaf or hearing-impaired people: the material, wood or metal, conducting the sound instead of the air. The musical instruments are connected to computers—sometimes tied to the body of the musician—that amplify the vibrations they produce. They are also connected to synthesizers and amplifiers that increase the sound for hearing people. There were ten different instruments designed by Tarek Atoui or by other creators. Among which were a set of wooden drums created by Thierry Madiot and ink drawings by Julia Alsarraf—by touching an ink drawing prepared beforehand the musician could produce diverse sounds and rhythms—or the amazing 33 Soft Cells, created by Tarek Atoui, made of thirty textiles panels of diverse textures which, on contact, produce different sounds.

There were public rehearsals in preparation for the four weekly concerts. During the concert I attended, two hearing-impaired people and two hearing people played. Spectators were invited to hold a balloon in their hands during the concert so they could experience the sounds both acoustically and through touch: their hands thus became another listening receptor. The hierarchy of their senses was suspended and sometimes even transformed, their attention shifting from one sense to the other. The concert also incorporated the visual aspect of perception: the audience could see the performers changing places during the concert, going from one instrument to another, playing on the same instrument together, or playing several instruments at the same time. Each concert was different, the performers never being the same, and free improvisation was central. From a traditional or modern musical point of view, the concert I attended was peculiar but it also was a moving and beautiful combination of sounds, noises, and musical notes.

Umeda, Composite. Photo: Titane Brentzer.

Composite by Tetsuya Umeda, presented at the Brass, a building of the Wiels—a former brewery that has been converted into an art center—was another surprising, singular and exceptional production, based on the rhythm of the performers´ movement, without any text or story. The production involved around twenty-five non-professional actors who rehearsed for a week before the first public performance. The space chosen was a large room, divided into two parts by some of the engines that were used when the place was a brewery. The windows opened onto a balcony from which the audience could see a meadow and, on the right-hand side, a small lake. When the audience entered this space, three actors were walking awkwardly, following a regular pattern, without interruption. They used very simple movements, for example, touching their arm with their opposite hand in three places before touching their chest, walking all the while in very little steps. They followed simple binary, ternary, and quaternary rhythmic patterns that changed regularly. They made a sound that stressed the meter used. Meanwhile a performer, Tetsuya Umeda himself, installed a sort of suspended sculpture, a glass pitcher full of water hanging over a container and illuminated from behind. The other performers continued to move without paying him any attention. A sound track, made up of industrial noises, electronic music, and distorted voices, accompanied the production. Progressively, other performers who had been placed among the public joined the performers on stage, adapting their movements to their personalities and their physical features: a young woman used very nervous and energetic movements; a large, tall man only performed the last part of the movement, making a distinctive sound. Meanwhile, the audience moved about freely, seeing different images depending on where they were standing.

For me, the piece represented the alienation of the factor workers, progressively becoming a wider metaphor, maybe of our lives, but everyone was free to interpret the performance as they wished. At one point, some of the performers gathered in a circle; then, in a winding line, they all went onto the balcony and then down to the green illuminated meadow. There, they formed another circle, using the same rhythmic movements as before. Some of the images thus created seem to recall Magritte’s paintings, with lights shining in the middle of the night. On the lake, in the water, a light shone, and bubbles seemed to spurt out from it. One of the performers crossed the lake slowly in a canoe, and a few white balloons, suspended in the air over the water and illuminated from the bank, drifted in the wind. An illuminated suburban, passing regularly about one hundred meters in front of the balcony, became part of the performance. Somebody advised the audience that the production was over, but the performers carried on, wandering through the space, dissolving the limits of the end, and part of the audience remained to watch the unexpected beauty of these endless movements.

Regy, Reve et Folie. Photo: Palcal Victor.

Rêve et Folie, directed by Claude Régy and based on poetic texts by Georg Trakl, was another outstanding production challenging traditional perception of time and duration. The figure of a single actor, Yann Boudaud, appeared and disappeared as the light changed from absolute darkness to half-light, to create a mysterious non-realist atmosphere against the backdrop of a huge circular arc, devoid of any decoration or color. To me, the scenography and the delivery of the text, slow and clear, with words intoned and pronounced in ways never heard before, evoked the indefinable mystery of life.

Barba, slugs’ garden. Photo: Koen Broos.

Another production that challenged traditional theatrical perception was the surprising slugs´ garden/cultivo de babosas, created by Fabián Barba and Esteban Donoso. The performance was centered upon tactile sensations, rather than the more conventional sight or sound. The audience, divided in small groups, was taken into a room by a guide. There, they had to leave their coats, backpacks, shoes, mobile phones, and watches, and then, one by one, they were taken barefoot into a large covered courtyard, in front of the beautiful façade of the seventeenth-century palace la Bellone. In the courtyard stood a structure made of wood panels and fabrics of different vivid colors, covered with a grey canopy, and resembling a huge snail. In its circular interior lit with smooth light, the floor was covered by all kind of fabrics and cushions, with an incredible range of different weaves. Each spectator was taken to a specific place within that space and invited to sit down. Within this space, ten performers were rolling about on the floor with their eyes closed; they had turned into “slugs.” The slowly-rolling slugs touched the members of the audience, lay partially on them, and left. Carried out in complete silence, the performance depended solely on tactile sensations, and how the individual responds to them. The spectators could choose to stay inside for the three hours that the performance lasted, or leave. There was no plot, no other fiction than the fact that the slugs were performed by professional actors.

Erciyas, Voicing Pieces. Photo: Begum Ecriyas.

Voicing Pieces by Begüm Erciyas, already presented at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in 2016, was another example of immersive performance; isolated in a soundproof booth, the spectator was invited to read a text displayed in front of them. Hearing their own voice, combined with diverse acoustic effects, they thus took part in an experiment of hearing.

Edvardsen, Time has fallen asleep. Photo: Titane Brentzer.

Among the striking experiences the visitor could enjoy at the festival was Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine, an experimental collaborative project focused on the relationship between reading and memory. It was subtitled “A library of living books, a reading room, an exhibition, a workspace, a publishing house, a bookshop” and directed by Mette Edvardsen, a Norwegian choreographer currently living in Brussels. The experiment began there in 2010, as the result of a reflection on how theatrical texts are learned, on the work done during rehearsals, and about what parts of the production should or should not be preserved for the future.

The performance itself was preceded by a long preparation. A contributor selected a book in agreement with Mette Edvardsen, and learned parts of it by heart, becoming thus a “living book.” At present, the “living library” includes almost seventy people who know a book or part of it by heart. The range of books is very diverse, including Goethe’s Faust, Runaway by Alice Munro, Answered Prayers by Truman Capote, Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, and Orlando by Virginia Woolf. The books are learned in many different languages, including English, French, Flemish, English, Spanish, Italian, German, Russian, Polish and Arabic. The second step is the performance itself. The spectator makes an appointment to meet a “living book” who will recite a book to them, their single spectator. On Saturday, May 27, Vincent Dunoyer recited to me—although he explained that he was “reading” to me—his text, the second chapter of Monsieur Songe by Robert Pinget, as if it were a normal conversation in which one of us was telling a story to the other one. He did not emphasize any episode in particular; he remained very close to a neutral reading and yet seemed like an interpretation. At the end of this personal performance, which lasted around thirty minutes, he answered my questions.

The third step, for some of the “living books,” consists of rewriting the book they have learned. Many of these rewritings have already been published as part of the project. For example, Vincent Dunoyer has published Mon Songe, his rewriting of a part of Monsieur Songe, with the Editions de Minuit. Being a “living book” is thought of as an ongoing activity, never fully accomplished, and periodically the members of this project gather, not only when they are invited to perform, but also to work together. The experiment also includes an exhibition where are displayed all the books that have already been learned—the “living library”—as well as the books that are waiting to be read by somebody—the “shadow library.” The visitor can take them off the shelves, sit down at a table, and read. There are also public lectures with fascinating and profound reflections on reading, learning, and how texts are received and assimilated by the reader’s body.

Bruguera, Endgame. Photo: Estudio Bruguera.

The Kunstenfestivaldesarts pays special attention to the relationship between the performance and its location, with productions are staged in many parts of Brussels. For example, a production of Beckett’s Endgame, directed by Tania Bruguera, took place in the former Théâtre Marivaux, now a huge empty space with concrete walls. Inside, a scaffolding was erected around a huge cylinder of white fabric. Each spectator was ushered up to one of the three levels of scaffolding and taken to stand in front of an opening in the white fabric. There, the audience had to put their heads through the opening so they could see the full scene: a stage, at a lower level, where the actors performed, surrounded by a huge cylinder of white fabric dotted with the heads of fellow spectators. Those who watched the production thus became a part of the scenery, recalling Beckett´s dramaturgical world, where the image of bodiless heads recur in his later works. The setting also evoked the arena of a circus, a disused operating room in which only suspended heads remained, or an aseptic science fiction space. The overall impression was one of emptiness, which succeeded in magnifying both Beckett’s metaphysical concerns and the play’s claustrophobia. The representations of Hamm and Clov—performed by Brian Mendes, and Jess Barbagallo—also introduced some new details. Hamm was in a contraption that looked more like a wheelbarrow than a wheelchair, with his feet dangling out at the front. Clov, bare-chested and walking clumsily, moved around the enclosed space, and climbed the wall—putting his hands in cuts in the fabric to get a hold of the hidden scaffolding, to open a tiny hole representing the window Hamm has asked him to look through. Nell and Nagg were not in trashcans but in two large tubes coming out of the cylinder’s bottom. Both characters were played by young actresses who did not speak, their parts being recited by offstage voices—Jacob Roberts and Chloe Brooks—summoning another recurrent device used in Beckett´s later plays.

Danse de nuit, an extraordinary dance production by Boris Charmatz and the Musée de la danse (the national choreographic center of Rennes and Brittany), took place outdoors in a public space, the huge empty top floor of a parking lot in the middle of Brussels, with a view of the whole city. It was getting dark when the production began at 10pm. Four people carrying floodlights on their backs moved around the space. When they stopped, they created spaces in which the dancers were illuminated. At the beginning of the production, the six dancers—Ashley Chen, Boris Charmatz, Olga Dukhovnaya, Julien Gallée-Ferré, Jolie Ngemi, and Marlène Saldana—began in separate spaces and then gathered in the same circle. The audience followed the dancers, who moved very quickly, creating new spaces, merging frequently with the audience and speaking to them. Sometimes, the men carrying the floodlights moved independently of the dancers, and the dancers continued their movements in the semi-darkness, as silhouettes.

Each of the dancers was dressed in a different way, most of them wearing vivid colors that evoked a carnival vocabulary. The dance included six solos, but the dancers gathered very often to create collective movements. The movements were extremely diverse, but also very concentrated and intense. Some were inspired by modern urban dance but they were transformed or unfinished—glimpses rather than references. Other movements seemed as if they had been taken from everyday life, and transformed, rejecting the uniformity of a single style. Against the asphalt of the top-floor parking lot, the movements often seemed voluntarily rough, at one with the drab urban space.

While dancing, the performers uttered texts, although dance was the dominant element of the performance; during the opening scene, each dancer spoke, but later, a single text was recited by each dancer in turn, emphasizing the plurality of the speakers. The flow of the text created the impression that the text had been put together quickly, maybe just before the show, an impression contradicted by the precision of the movements.

The fragmentary texts were taken from radio broadcasts, videos, and other texts. The words, often colloquial, flowed quickly and constantly. They created a mix of personal recollections, desires, and unleashed sexual obsessions—as if the darkness of the night in this place dissolved boundaries—artistic problems, poetic questions—for instance, how humor can lose its comicality very quickly, as in Reiser´s drawings—contemporary political problems—such as Islamism, terrorism and the killing of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists—and reflected on the need to maintain the freedom of thought and action. The words, as well as the movements, were provocative—an audacious exercise of freedom, aiming to open the spectator’s mind and to keep the imagination alive. The words and the movement never coincided but overlapped, only sometimes dealing with the same topic. The dancers’ voices, as well as their movements, were rapid and most of the sequences followed each other briskly, as if they were impelled by an urgency to communicate.

De Buysser in The Tip of the Tongue. Photo: Danny Willems.

The Tip of the Tongue, by Pieter De Buysser, was an interesting attempt to dramatize the scientific explanation of the universe and another example of an original use of space. It is a science-fiction story, inspired by the nineteenth-century astronomy performances presented at the Planetarium of Brussels. Inside the dome of the Planetarium, under the semi-sphere of the artificial sky, diverse images of the sky, stars, and galaxies were projected. The performer, Pieter De Buysser, took his place in the middle of the circle under the highest point of the dome, standing on a platform that another performer pushed in circles, mimicking the movement of a planet, throughout the entire production. The audience could hear a voiceover, presumably the performer´s voice, narrating a complex, multilayered, fictional story that grew in complexity, which was interwoven with an explanation of the universe, including, finally, the eleven levels of String Theory. The complexity of the story and the variety of the images contrasted sharply with the single physical movement of the performer and the circles of the platform.

The Kunstenfestivaldesarts also tackled political issues. While in Europe, nationalist parties have achieved unprecedented percentages in the polls, and the control of immigration has become part of the program of far-right parties, the Kunstenfestivaldesarts stressed the need to cross borders, from an artistic point of view.

This year, the WIELS, a former industrial brewery transformed into a museum of modern art, focused on multilingualism, cultural exchange, and reflection upon current social problems, became one of the important locations of the Festival. There, the exhibition The Absent Museum took place, showcasing the works of almost fifty contemporary artists—such as Gerhard Richter, Thomas Hischhorn, Lili Reynaud-Dewar and Oscar Murillo—who are all, in some way, tied to Brussels and its region. This inspiring exhibition demonstrated a model of a future museum in the capital of Europe. Promoting self-analysis and self-criticism, and rejecting the museum as a tool to transmit the normative nation-building of the past, the exhibition was committed to cosmopolitanism and expressed the desire for the museum to be a critical space promoting a reflection on today’s world. The diverse works of art displayed explored difficult issues and controversies, both contemporary and historical, such as: identity and multiplicity; the division of Europe; Western supremacy; decolonization; racial, gender, and social inequality; migration; and the consequences of the globalization. Additionaly, there were works that explored art as a transgression of norms, war and violence, and our tendency to shy from their reality.

A few productions were performed in the WIELS, further exploring cross-disciplinary art practices. One was The Guided Tour – Once We Shared Consequent Masturbation, by Nástio Mosquito, was a guided tour of the exhibition The Absent Museum. Stopping in five rooms, he tackled some of the main topics of the exhibition, making the audience reflect on some of the works exhibited and about the general purpose of this exhibition. Among them, Small Tragic Opera of Images and Bodies in the Museum by Lili Reynaud-Dewar was a performance by eight immobile singers wearing dresses normally displayed on eight mannequins during the day. They sang texts written about the dresses from varying points of view—the museum staff, a curator, an art critic, the community, the activist artist—and reflected upon the main topics of the exhibition. They asked questions about what a show in a museum should discuss, what an exhibition should be about, how to give a real life to a body, how to cope with sensitive content, how to view the bodies of others, how an artist can produce something real, and the disorientation of the public faced with modern art.

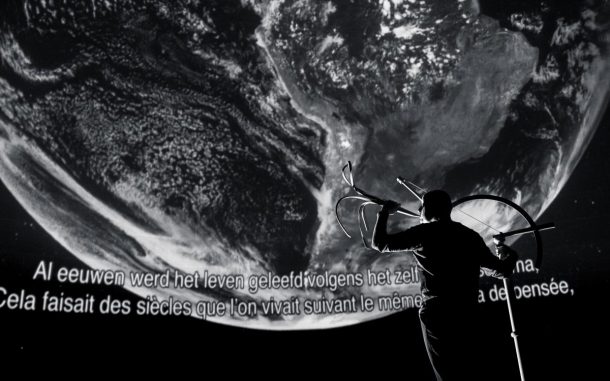

Rau, Empire. Photo: Marc Stephan.

One of the most successful productions in the festival was Empire by Milo Rau and The International Institute of Political Murder, the final part of a trilogy about Europe composed of Civil Wars (2014) and The Dark Ages (2015), dealing with migration in Europe, the war in Syria, and its broader consequences. The title, Empire, alludes to the borders that were arbitrarily traced by French and English empires to divide Kurdistan and Syria, as well as the current border control and asylum system in Europe, a topic very present at the festival. The most surprising feature of Milo Rau´s production was that the actors were real migrants, who narrated their own stories: the Greek Akillas Karazissis, the Jewish actress Maia Morgenstern, living in Romania, the Syrian Rami Khalaf, and the Kurd Ramo Ali. When Rami Khalaf says he has immigrated to Scandinavia with a false passport and produces it on stage, the audience can imagine that this is the document he actually used. The contributors’ words seemed more real than usual speeches made by actors on stage.

The music by Eleni Karaindrou, who wrote scores for Angelopoulos´s films, which combine folk traditional, classical and modern elements, followed the production like a motion film soundtrack, softening the violence of the stories. At the beginning, the scenography consisted of the ruins of an ancient, burned stone house. Then, the four actors turned the revolving stage to show a single room—a kitchen that contained a table and a bed—thus evoking the life of the migrant; the ruins were behind, in the character´s past. There was a large screen above the room and, on the right-hand side of the stage, a camera.

On stage, three actors spoke one-by-one, looking at the camera while the close shot of their face was projected on the screen facing the audience. The acting, mostly limited to the face, was moving, although they told their stories quietly, with distance; they never cried or raised their voices, often speaking coldly, as did Maia Morgenstern, and sometimes ironically, in contrast with the horror and the pain implied by the situations described. The production was divided into five parts, like the five acts of a tragedy, representing the stages of their migrations.

The stories were often linked; Eleni Karaindrou wrote Angelopoulos´s film score, Maia Morgenstern played in Angelopoulos´s films on Greek myths; the Greek Akillas Karazissis, like Maia Morgenstern, has played many Greek mythical characters, and the audience is reminded that Greece and the Middle East are the cradles of European culture and of theatre. Their stories were different, but they showed that the migrants shared a common experience. The Romanian Jewish actress presented her journey as international performer far from home, abandoned by her husband and one of her daughters. Akillas Karazissis travelled to Germany in the 1970s, and explained how Greece has completely changed since the beginning of the economic crisis. Ramo Ali, from western Kurdistan, explained how after having been tortured in a Palmyra prison, he fled his country and sought refuge in Europe. The Syrian Rami Khalaf explained the deteriorating conditions in his country that forced him to leave. He told of how his brother disappeared and how he tried to find him among the photos of people who had been tortured and killed, which a photographer who worked for the regime had taken. A few of the photographs were projected on the screen, until he recognized his brother. The fourth part of the production concerned the topic of mourning, and the fifth was entitled “Homecoming.” Rami Khalaf explained that he was able to return to his town, Qamichli, but that all his friends had died and everything had changed so much that he could not live there anymore. Three of the actors cited the deaths of their parents as the final rupture of the link that tied them to their native country.

Shahmiri, Voicelessness. Photo: Roberta Cacciaglia.

Voicelessness, by the Iranian theatre director Azade Shahmiri, featured elements of science fiction and crime stories, although the main topic of the play was the memory of a painful past and how the character coped with it. The action was set in the future, on December 10, 2070. A young woman, played by Shadi Karamroudi, spoke with her mother—who had been in a coma for two years, thanks to a science-fictional device—because she wanted to reopen an enquiry to know who killed her grandfather, more than 50 years ago, in 2016. The crime could be taken to court again, with a virtual jury, which was supposed to be more impartial. The mother, played by the director herself, also appeared as a young woman at the time of the crime. The author of the crime was finally unmasked: it transpires that the grandfather was betrayed and robbed by his closest collaborator and friend, who finally killed him. However, there is no relief and the mother does not authorize her daughter to start a new trial. The images were sharp. The light design by Ali Kouzehgar stressed the empty space, the space of grief. The production was very precise and sober; the two actresses never smiled or laughed. The dialogue was very tranquil, and there was not a single moment of joy or happiness. The scenes were interrupted by five films projected on the screen, but they did solve the situation, only reflected an atmosphere of suspicion about the judicial system and a climate of oppression, without these ideas being ever mentioned by the characters.

Bellinck, Simple as ABC #2. Photo: Thomas Bellinck.

Simple as ABC #2: Keep Calm & Validate by Thomas Bellinck and ROBIN was an interesting and explicitly political production that tackled the problem of immigration. The production evoked a Brechtian alienation through ironic dialogues and the use of several devices. With two singers and three musicians playing two violins, a horn, a drum kit, and a xylophone, it was a mixture of musical and satirical opera. The singers walked against the direction of a revolving stage to symbolize the criticism within the text. A few curtains were hung in a semicircle around the revolving stage. On them, diverse images were projected: two men in front of their computers controlling the number of migrants, a meeting of politicians, a refugee camp, a vault where all the information about the refugees was kept. The performers wore tracksuits with a stripe on the side, which gave them a military quality, evoking both the border guards and the migrants themselves.

The lyrics of the songs offered a deep and harsh criticism of the European position on immigration, emphasizing the repressive and destructive measures taken, notably the collection and classification of personal information used to control of the immigrants while ignoring the specific problems of those human beings. Many painful anecdotes were reported, concerning a failed rescue in which a mother lost two of her sons at sea, human trafficking, and how people cut off their fingertips to prevent identification. The production was divided into sequences that covered an impressive range of the problems tied to illegal immigration, although the repetition of patterns made it occasionally predictable.

Spångberg, Gerard Richter. Photo: Anne van Aerschot.

There were a few outstanding dance productions, like Bacantes – Prelúdio para uma Purga, (Bacchantes – Prelude to a Purge) by Marlene Monteiro Freitas, or Dança Doente by Marcelo Evelin and Demolition Incorporada, a Brazilian dance production influenced by Butoh. Also, mixing dance and theatre, Gerhard Richter, une pièce pour le théâtre by Mårten Spångberg was concerned mainly with aging. The stage was covered by a colorful carpet that looked as if it were made out of cow skin; the ten dancers, most of them in their forties, having passed their “peak period” as dancers, wore vivid and colorful summer clothes. The production seemed to underline a change in life when hectic drive is replaced by repetitive and calm movement. The production belonged to the “no dance” movement, and was clearly influenced by Yvonne Rainer’s theories. At the beginning, some of the movements were very limited, always seeming to arise from immobility. The non-figurative free movements were mostly slow, separated by pauses, with repetitive rhythms. This series produced a relaxed atmosphere, a flow of movements without climax. There were always a few actors on stage who remained immobile. One of the most surprising aspects was the text spoken by the dancers, their calm and soft voices neutral, with no important pitch variations. They spoke side by side, looking at the audience, never at each other. The text consisted of seemingly indifferent reflections on everyday life and anecdotes about sex, children—mainly about aging and maintaining one’s energy levels. At times, during pauses, there were moments of complete silence, without movements, underscoring the tranquility of the dancers. There was no dramatic tension. Two large lamps hanging over the stage were turned on slowly, twice, to signal the two parts of the production. Part of the text was repeated in the second part of the production, creating an impression of suspended time.

Pensotti, Arde brillante. Photo: Grupo Marea.

Humor wasn’t absent from the festival. Among the comedies, On traversera le pont une fois rendus à la rivière (We will cross the bridge once close to the river), by Antoine Defoort, Mathilde Maillard, Sébastien Vial and Julien Fournet of L´Amicale de Production, satirized multimedia and theatrical productions based on real-time communication through the internet. Philip Seymour Hoffman, par exemple, by the Argentinian Rafael Spregelburd and Transquinquennal, was a parody of the transformation of the actors’ identity. Arde brillante en los bosques de la noche (Burning bright in the forest of the night) by Argentinian author and director Mariano Pensotti, dealt with a variety of political topics. The guiding thread was the relationship between Communist ideology and feminism, using the hundredth anniversary of Russian Revolution as a pretext. The comedy stressed the contradictions between ideology, what is presented as a good way of life, and personal drives and ambitions. The humor was enhanced by the complex structure of a production that, like some Russian dolls, contained three levels, with a witty system of repetitions and variations between them, and with different characters played by the same actors.

The production began with a puppet show, in which the main puppet was an image of its puppeteer, dressed identically. The puppet was a female Marxist professor appearing on a stage lit by only a red light and discussed the relation between Communist ideology and feminism. The female puppet resembled the Russian Communist Alexandra Kollontai, who worked for women´s emancipation, sexual freedom, and against the influence of capitalism on women´s bodies. In this play, some of her descendants have immigrated to Argentina and established a community of women in the forest there, based on her theories. The other puppets epitomized several clichés: her husband, another professor, who breaks up with her to live with a student; her daughter, who is studying to become an actress; and the students who celebrate their graduation.

The puppets went to see a theatrical show, played by the human actors, depicting the life of a lower-class family in which one of the daughters returns after joining the FARC, the Colombian Guerrilla movement. After the happiness of the reunion, the family was confronted with the reality of their low-level jobs, and their desire to take economic advantage of their sister´s feats. In light of the returned sister’s problems, the feminist topic of women emancipation appears once more.

Later, the family decides to go to see an Argentinean film, played by the same performers. Here the acting became more realistic. The film showed how a presenter with feminist and politically Leftist ideas is promoted, and to celebrate, three female friends decide to travel to a forest to spend a fun weekend in a community of descendants of Russian immigrants. The main character gets involved with a male descendent of Alexandra Kollontai, falls in love, but finally discovers that the man exploits women in a factory, ironically ending the Communist dream. In the final part of the structure, the production goes briefly over the two previous parts, self-parodying the production itself.

Manuel García Martinez is Senior Lecturer in French Literature at the University of Santiago de Compostela. He wrote his Ph.D. in Drama Studies at University Paris 8. His research interests are time and rhythm in theatrical productions/performances and in dramatic texts, the French contemporary theatre, and the Canadian theatre.

European Stages, vol. 10, no. 1 (Fall 2017)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 2017 Avignon Festival: July 6 – 26, Witnessing Loss, Displacement, and Tears by Philippa Wehle

- A Reminder About Catharsis: Oedipus Rex by Rimas Tuminas, A Co-Production of the Vakhtangov Theatre and the National Theatre of Greece by Dmitry Trubochkin

- The Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2017 in Brussels by Manuel Garcia Martinez

- A Female Psychodrama as Kitchen Sink Drama: Long Live Regina! in Budapest by Gabriella Schuller

- Madrid’s Theatre Takes Inspiration from the Greeks by Maria Delgado

- A (Self)Ironic Portrait of the Artist as a Present-Day Man by Maria Zărnescu

- Throw The Baby Away With the Bath Water?: Lila, The Child Monster of The B*easts by Shastri Akella

- Report from Switzerland by Marvin Carlson

- A Cruel Theatricality: An Essay on Kjersti Horn’s Staging of the Kaos er Nabo Til Gud (Chaos is the Neighbour of God) by Eylem Ejder

- Szabolcs Hajdu & the Theatre of Midlife Crisis: Self-Ironic Auto-Bio Aesthetics on Hungarian Stages by Herczog Noémi

- Love Will Tear Us Apart (Again): Katie Mitchell Directs Genet’s Maids by Tom Cornford

- 24th Edition of Sibiu International Theatre Festival: Spectacular and Memorable by Emiliya Ilieva

- Almagro International Theatre Festival: Blending the Local, the National and the International by Maria Delgado

- Jess Thom’s Not I & the Accessibility of Silence by Zoe Rose Kriegler-Wenk

- Theatertreffen 2017: Days of Loops and Fog by Lily Kelting

- War Remembered Onstage at Reims Stages Europe: Festival Report by Dominic Glynn

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016