The major event at the Deutsche Oper in November was the premiere of The Huguenots. The publicity preceding the opening emphasized two aspects. First, the tenor in the leading role, Peruvian Juan Diego Florἑz, was described as the best tenor in the world today. Second, the opera would last five hours. One plus and one minus for most people, but it was so exciting to the public that all performances quickly sold out even before the premiere and the subsequent rave reviews.

The first performance of the opera by Giacomo Meyerbeer (with a libretto by Eugene Scribe) was in 1836. Neither the opera nor the composer had much success after that, but some people considered the composer undervalued. Director David Alden hopes to change that. A Deutsche Oper production of the opera in 1987 lasted only two and a quarter hours. Alden believes that the richness of the music and such elements as the tableaux vivantes related to the history of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre demanded the many hours of this production. He noted that the abuse of power and suppression were always the themes in Meyerbeer’s works, which “gave them a political dimension which is as relevant today as it was 180 years ago.”

There was no question of the success of Florez as the naïve Huguenot Raoul. His voice, his appearance, and his acting fulfilled all expectations. But with such a “grand” opera, that was not all that the spectators found thrilling. The conductor Michele Mariotti said, “All in all, the opera requires seven world class singers.” The production had these too – singers who were called for curtain call, after curtain call, in the already long evening.

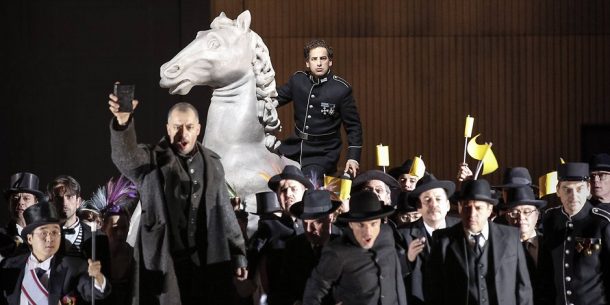

The opera was beautiful in many ways. The period costumes were gorgeous and elegant, particularly those of the queen. She and the others appeared on larger-than-life statues of white horses, three of them nearly filling the stage. One scene featured dozens of paintings of people from the period creating a magnificent background. Naturally, given the subject matter, the climax involved explosives, shooting, five giant burning crosses, and the central characters slaughtered for their beliefs — an exciting conclusion to a memorable performance.

A Scene from The Huguenots, directed by David Alden, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Deutsche Oper, Berlin.

One of the benefits of a major opera like the Deutsche Oper is that one can see in the same week a startling modern interpretation of an opera like The Huguenots and a continuously popular opera from the past such as, Tosca, which premiered in 1969, and has been performed 381 times since then.

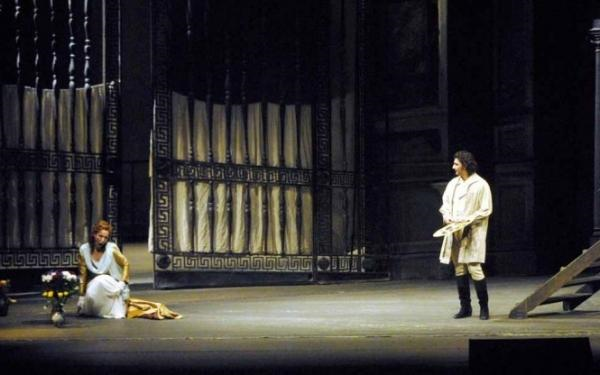

A full house was enthusiastically receptive from the first view of the setting to the last moment when Tosca leaps to her death. The fully realistic recreation of the interior of the Church of Sant’ Andrea della Valle in Rome created a sense of beauty, mystery, and deeply felt belief. The latter was evident in Tosca’s adoration of the Madonna and in the final moments of Act 1, when the evil Scarpia throws himself to his knees in prayer, and then fully abases himself as the menacing music rises to a climax.

The final setting was the most impressive with a massive wall of the prison situated stage left, and a view of Rome at the back. As it began, this view was nearly in darkness, but as the scene progressed the buildings of Rome became clear with the dawn as Tosca and Cavarodossi stood hand in hand singing about their happy future. Anja Harteros and Jorge de Leon as the passionate lovers were perfect. One expects Scarpia to be powerfully impressive in voice and presence, but Lucio Gallo truly seemed extraordinarily so, and the audience responded with cheers and shouts to him and the others.

A Scene from Tosca, directed by Boleslaw Barlog, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Deutsche Oper, Berlin.

Given the presence of three major opera houses in Berlin, plus smaller houses and visiting companies, there is always opera in the air. It was present as well in a play which was new for the season at the Renaissance Theatre. Following up on the success of Ronald Harwood’s Decadent Art last season, the Renaissance Theatre presented his play Quartetto. It has a very simple storyline involving four opera singers of renown, now living in a seniors’ home. To relive some of their former glory they plan to sing the quartet from Rigoletto.

It is always impressive to read the notes about the performers in this house. The small and beautiful theatre from the 1920s attracts performers of the highest class. In this instance, the performers not only had to be fine actors but, and more importantly, fine operas singers as well. The information on Karan Armstrong, Rene Kollo, Victor von Halem and Ute Walther boasted of a stunning list of starring roles in opera from Bayreuth, Paris, La Scala and other operas throughout the world. Their performances were radiant and the last scene was quite thrilling. The four singers, formally dressed, stood before a projection of a large, elegant opera house and performed the dramatic quartet from Rigoletto with intensity and vigor.

A Scene from Quartetto, directed by Ronald Harwood, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Renaissance Theatre, Berlin.

Harwood’s picture of these four characters was a statement about the life of seniors, and struck a positive note which clearly appealed to the present-day audience.

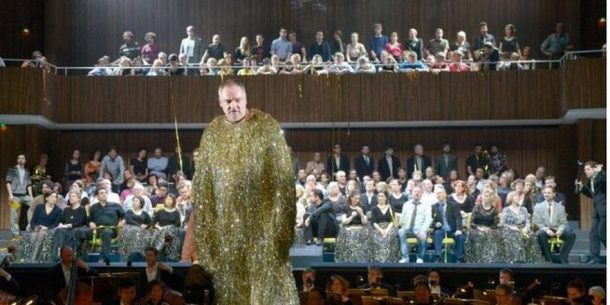

An actual production of Rigoletto was in the November plan at the Deutsche Oper. It had been in the repertory for scarcely a year. The opera directed by Jan Bosse was notable for a number of oddities. Despite the many references in the text, Rigoletto was neither a humpback nor a cripple. The acting space was completely filled with rows and rows of theatre seats so that in one major scene the only movement of Rigoletto was changing seats in the front row. The contemporary costumes included a bright pink suit with a pink and green shirt for the Duke and a swishy, silver spangled sort of gown completely covering Rigoletto’s body and head. The strength of the cast was clear and also indicated the breadth of international performers in the Deutsche Oper productions. Yosep Kang was from Korea, Siobhan Stagg from Australia, and Francesco Landolfi from Italy. Their successful appearances in many countries include productions of Rigoletto and numerous other operas.

A Scene fromRigoletto, directed by Jan Bosse, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Deutsche Oper, Berlin.

Madame Butterfly invites beauty and sensitivity in the staging, and it had those qualities in the Staatsoper presentation. It has been in the repertory since Eike Gramms directed it in 1991 with costumes and scenery by Peter Sykora. The first act built up to a spectacular conclusion with Butterfly in her white wedding dress, Pinkerton handsome in his white uniform, and behind the screens of the house, the effect of a star-filled night as the two sang of their love.

In a good production like this, one realizes how important Butterfly’s maid Suzuki and the American Consul Sharpless are. Katharina Kammerloher and Alfredo Daza are fine performers who helped convey the strength of the opera. As Pinkerton, Dmytro Popov was a wonderful tenor with a strong full voice and charisma. But, of course, the opera hangs on the performance of Butterfly. Here Svetlana Aksenova fulfilled every hope. Her voice was superb, and her graceful movements and gestures were the embodiment of all that Pinkerton says about her.

A Scene from Madame Butterfly, directed by Eike Gramms, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Staatsoper, Berlin.

Sykora’s setting utilized simple, typical Japanese screens on a raised playing area. The unusual element was that they did not enclose the house. On one side the audience could see a shop with occasional activity, and on the other side and behind, were areas where the relatives and the priest arrived, and where Kate Pinkerton waited to take away the child. In this area, there was also a tall pole with an American flag, which was raised as Puccini’s music referenced America. The changes from full moon through the night, as Butterfly waited, to blazing sunlight in the morning were very effective. The tragic ending with Butterfly lying dead and the frantic entrance of Pinkerton shouting, “Butterfly, Butterfly” was intensely moving.

Beautiful scenery was also part of the pleasure of the two ballets performed by the Staatsballet. The choreography and the staging of Sleeping Beauty by the director of the Staatsballet, Nacho Durato, made it clear that he is as successful with classic ballet as with his modern ballets which have been so popular. In those, the dancers are often in contemporary clothes or nearly nude, dancing on a bare stage. In contrast, this is a lavish, spectacularly staged production.

The costumes and settings were designed by Angelina Atlagic. It was evident in the opulent beauty that filled the stage why she has won so many prizes and is invited to theatres world-wide. The first of the four settings was the palace with four white baroque-style frames from the front to the back of the stage. Here, the court ladies in beautiful floor-length dresses, were entertained by dancers in fanciful tutus of delightful colors. This was interrupted by black-costumed dancers who spread a giant black silky cloth over the dancers, moving upstage, only to yank it off to reveal the evil fairy clad in a bejeweled black satin dress with a train which she swirled and twisted as she put her curse on the princess.

The second act was the occasion of the princess’s 16th birthday. After she pricked her finger and fell to the floor, apparently dead, the curse was altered by the Lilac Fairy to be one hundred years of sleep. Next, the stage darkened and great black branches descended, covering everyone.

So it went, with one dramatic effect following another – gorgeous trees forming a cover over the stage, the Lilac Fairy and the rescuing prince gliding by upstage in a boat on a lake, and in the conclusion of the last act, dancers spreading an enormous white, lacy cloth over the depth of the stage which, as it sank, became the elaborate train of the princess’s wedding dress.

The dances of the major characters were wonderful to see and were enhanced by the numerous “specialty dances” typical of Tchaikovsky’s ballets. Some of these were the jewel colored companions of the Lilac Fairy and other couples from fairy tales. The audience particularly responded to the charm of the dancers whose costumes suggested kittens who bounded, fought, and embraced.

The Staatsballett production of Giselle is not as spectacular as Sleeping Beauty but it was engrossing and mysterious, and one can understand why it remains in the repertory even after sixteen years, and is the most performed ballet in the world. This “ballet blanc” was performed first in Paris in 1841. The mysterious, fantastic quality of the story has inspired many writers, and is considered to be the epitome of romanticism in ballet. The first act shows a village holiday in which Giselle dances with a stranger. At the end of the act, he is revealed to be an imposter and she goes mad — dancing herself to death in a stunning display of ballet technique and pathos.

The second act is really white. The scene is a lonely place in the woods where Giselle’s lover has come to place flowers on her grave. The trees overhanging the stage are ghostly white shadows. This is the place where the legendary “Willis” convene each night. They are women doomed to dance all night and lure young men to dance themselves to death. They appear as beautiful white phantoms who try to force the lover to dance until he dies. With the interception of Giselle (all in white with a great white veil) he is saved, and after a beautiful pas de deux, he is left to live as Giselle instantaneously disappears (via a star trap which one rarely sees used today).

A Scene from Giselle,with Orchester Staatskapelle Berli, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Staatsballet, Berlin.

In the role of Giselle the lovely Ksenia Ovsyanick followed famous dancers including Pavlova and Margot Fonteyn. She captured the delicate, magical quality of the role perfectly. A major part of the wonder of these two ballets was the rich, intense sound of the Staatskapelle Berlin.

Music was also a vital element in the Schaubühne Studio production of Brecht’s The Mother. Certainly one of his lesser known and infrequently performed plays, this innovative production has nevertheless created great interest, and it has been impossible to get tickets months ahead.

One of the main reasons was the presence of well-known Ursula Werner in the leading role. For many years, she was a part of the ensemble at the Gorki Theater starring in such plays as their legendary Three Sisters. In recent years, she has attracted international attention in films and in productions in Munich, Stuttgart, and elsewhere. In this role, she performed entirely with students from the Hochschule Ernst Busch. These eight students performed all the roles in this complicated play, and played many different instruments. The music which enthralled the audience was the notable score by Hanns Eisler. In the intimate theatre, they performed with great enthusiasm and made direct contact with the audience.

A Scene from The Mother, featuring Ursula Werner, 2016. Photo Courtesy: The Schaubühne Studio, Berlin.

The structure of the play is particularly interesting in the richness of the role of the mother. In the early scenes, she is very weak and totally uneducated and has very little to say. As the play progresses, her understanding and her own powers lead her to dominate the scenes. Especially powerful and impressive were the last moments when she stood alone on the stage speaking Brecht’s lines of hope and confidence, “Who still lives doesn’t say never . . . who loses still fights . . . The defeated of today will be the conquerors tomorrow.”

The direction by Peter Kleinert brought a freshness and excitement to this clearly dated play which rang a bell with the contemporary audience at these performances which have been sold out since January 2016.

The richness of startling new productions, and valued operas and ballets of the past create an intense aura in the theatres and opera houses in Berlin, that can be matched by few cities in the world.

has long had an interest in theatre and opera in Germany. She was the American Consultant for The Iceman Cometh at the Deutsches Theater. She presented several lecture performances for Amerika Haus including “Eugene O’Neill Onstage,” “American Women Playwrights,” and “Tennessee Williams’ South” which she now performs in Europe and America. She has written twelve books and continues writing and presenting papers at conferences.

European Stages, vol. 9, no. 1 (Spring 2017)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Cory Tamler, Managing Editor

Mayurakshi Sen, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Festival Transamériques, 2016: The Importance of Saying No by Philippa Wehle

- Ukrainian Contemporary Theatre as Cultural Renewal: Interview with Volodymyr Kuchynskyi, March 2015 by Seth Baumrin

- A Month in Berlin: Theatre for All Ages by Beate Hein Bennett

- New Productions and Revivals in Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- An Experiment of Strangeness: The 2016 Interferences International Theatre Festival in Cluj by Eylem Ejder

- A (Self-)Ironic Portrait of the Artist as a Present-Day Man: The Newest Trademark Show of Gianina Cărbunariu in Bucharest by Maria Zărnescu

- Do You Speak Silence?, asks Gianina Cărbunariu in Sibiu, Romania by Ion M. Tomuș

- Une chambre en Inde (“A Bedroom in India”): A Collective Creation by the Théâtre du Soleil and Ariane Mnouchkine by Marvin Carlson

- Only When in Rome?: Albert Camus’ Caligula at the Theater Basel by Katrin Hilbe

- Terrassa’s TNT Festival: The New, the Usual and the Ugly by Maria M. Delgado

- Puzzling Perspectives On Ever-Shifting Conflict Zones by Talya Kingston

- Sister Act(s): Catholic Schoolgirls Rule by Duncan Wheeler

- Re-framing the Classics: La Cubana Reinvent Rusiñol and the Lliure Revisit Beaumarchais by Maria M. Delgado

- John Milton’s Comus: A Masque Presented at Ludlow Castle: Shakespeare’s Globe, London by Neil Forsyth

- Musical in Bulgaria: A Mission Possible by Gergana Traykova

- What Happens to Heroes: Heinrich von Kleist’s Prinz Friedrich von Homburg at Schauspiel Frankfurt by Katrin Hilbe

- Krystian Lupa and Thomas Bernard in Paris, Fall, 2016 by Manuel García Martinez

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016