The Portuguese Association of Theatre Critics awarded its 2015 Prize to scene designer Cristina Reis, who devised a most creative and efficient set for Shakespeare’s Hamlet, produced by Teatro da Cornucópia. The production was directed by celebrated actor and director Luís Miguel Cintra and Reis, in a coproduction with the Almada Theatre Company, opening during the great theatre festival it stages every Summer in the city of Almada, that looks at Lisbon across the Tagus river.

However, it was not the first time that the Cornucópia theatre company received significant critical praise and the favor of audiences (a short review of its importance in the Portuguese theatrical system can be found in the special issue of Western European Stages, 18:1 [Winter 2006] pp. 15-22. Known as one of the most interesting Portuguese theatre companies devoted to a demanding repertoire (both classical and contemporary) and a most imaginative staging, Cornucópia approaches theatre classics (and some modern and postmodern plays) with both a faithful textual reading and imaginative staging; they are definitely not bound to the regular proscenium theatre, choosing instead a free and inspired mise-en-scène that “loosely” occupies the main hall, and places audiences on different sides according to deliberate choices by its director and stage designer, thus respecting what Cintra sees as the most proper to each particular text.

Looking back at its history since its founding in 1973, and its main claim of staging important plays (classical and contemporary, foreign and Portuguese), Teatro da Cornucópia has stood as a reference point for modern theatre in Portugal. However, some important stages of its history should be remembered: its first period—when Luís Miguel Cintra shared the direction with Jorge Silva Melo—ended with Melo’s choice to create his own theatre company, Artistas Unidos (United Artists) in 1995 that is devoted to more contemporary theatre writing.

From that date on, Cristina Reis has been sharing the direction with Cintra and different choices regarding the repertoire have been activated, adding to a classical repertoire some inspired philosophical and (more recently) even religious writings. Indeed, Teatro da Cornucópia keeps insisting on the importance of texts not only for their literary value, but also, and especially in more recent years, as challenges to think about or evaluate life according to ethical values. Moreover, while publicly announcing how Parkinson’s disease has been reducing his ability as an actor, Cintra maintains his commitment to theatre directing and allows himself very brief appearances onstage in less demanding roles, as he did in Hamlet, where he appeared as a third gravedigger and as Luciano, for example. That shows not only his affection for his stage but also his unpretentious—and generous—relationship with the audience, an audience that has been faithful, but not devoid of new converts as a younger generation has begun to attend.

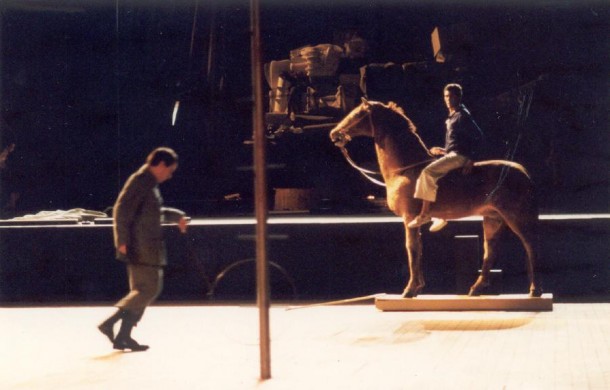

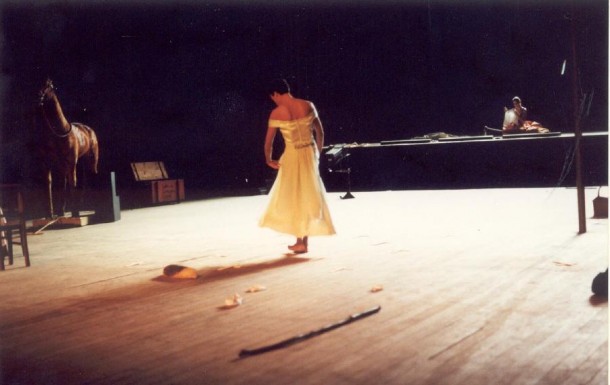

Hamlet co-directed by Luís Miguel Cintra and Cristina Reis, with set design by Reis. Photo courtesy of Teatro da Cornucópia.

Another important trait of this production was its attachment to an important and brilliant Portuguese poet recently deceased—Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen—who had translated Hamlet and who had accompanied this company either as translator (as was also the case of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing in 1990) or—at least once—as a real playwright. That was in 2002 with a very interesting play O colar (The Necklace) which triggered a light and most buoyant performance, directed and performed by Luís Miguel Cintra. It was moreover the only play she ever wrote and it was specifically dedicated to this theatre company.

Central to every Cornucópia performance staged since 1973 is Cintra’s idea that theatre is based on words and these should be presented for all their poetical value. But that idea should not involve recitation or exclusive concern for the dialogue. Instead, it is Cintra’s and Reis’s main concern—their fascination with stage design—that marks the difference, subjecting the words the actors articulate to an important relation to the set, costumes, and lighting. Therefore words are presented in contexts adding meaning and a deeper poetical insight to the performance itself.

The approach to this particular text of Hamlet, as described in the program, was triggered by the idea of—finally—using Sophia’s translation, finished in the 1980s and indeed meant to be awarded to Cintra’s theatre company. But, as he writes in the director’s note, Cintra had not staged the play out of “fear.” And that meant that now he—much older—was no longer able to play the title role. However, and as a demonstration of his maturity and generosity—he was happy to offer the title role to a young actor he met in Oporto, Guilherme Gomes. As he states in the program, it was probably the first time (among us) that Hamlet was played by an actor with the proper age of the character himself: young and immature. Hamlet’s fate in the tragedy is not easy, since it involves facing the consequences of his personal and political responsibilities, turning readers and spectators into the witnesses of a real moral—and political—dilemma. Cintra’s casting choice points to the tremendous legacy let by a corrupt and older generation: of Claudius, Polonius, political officers and a conflicted Gertrude, the tremendously powerful mother that poses as the alleging “mater dolorosa.”

Elaborating on the deep significance of this tragedy, Cintra writes: “I recognize in Hamlet the tragic portrait of a young generation whose parents’ amoral cynicism pushes him into a decisive cul-de-sac, and he is therefore unable to reconstruct life on political values that are anyway no longer acceptable.” He adds the idea that Hamlet is unable to adopt new laws still based on power and money that seem to repeat—as in our own days—their same oppressive coercion. Turning his eyes to our contemporary world, he adds: “I feel in my day-to-day life, as in other people’s, a most violent oppression by the money owners, who without showing their faces, make our lives impossible and our art with no interest since it turns out to support this condition as normal.”

Hamlet co-directed by Luís Miguel Cintra and Cristina Reis, with set design by Reis. Photo courtesy of Teatro da Cornucópia.

As for the distribution of characters, Cintra declares he was happy to give the new generation his deepest support, granting that it was a real transfer of spokesmanship, as he explains: “In my case, I was really sorry not to do be able to play Hamlet. However, to have discussed with Guilherme the building of the character has been, for me, one of the most rewarding tasks and the sweetest way of growing old.”

In Cintra’s opinion, both Ophelia (Nídia Roque) and Laertes (Sílvio Vieira) were composed as two unexpected but genuinely naïve characters “frighteningly pure or foolish,” while Rita Cabaço made of Osric a most brilliant and foolish presence onstage. Luís Madureira as the clown turned out to be a most interesting moonlit Pierrot, while Teresa Gafeira and Dinis Gomes added an intriguing edge—not devoid of cynicism—to the characters of, respectively, Queen Gertrude and King Claudius. Luís Miguel Cintra, in a most unassuming role as third gravedigger and first actor added a touching edge to the characters he played, either overstressing his belly or raising his voice when reading his lines.

This most ingenious distribution of characters and lively staging was an important feature of this performance that stood out as a landmark of an artistic elaboration on a classical text. And it is obvious that one of the most important pillars of its success was the stage design. Indeed this was—in my view—a decisive cornerstone of the whole production. It brought together some of the most important concepts that were explored in this play (such as confinement, spying, and betrayal), but also evoked a very personal feeling that matched director Cintra’s appraisal of this play.

Cristina Reis conceived a most prodigious stage setting that combined the idea of a crown and that of a dungeon, at the same time that it inserted a plain area—close to the audience—that was yellow colored, possibly suggesting the sand where Ophelia was to be buried. Between the entrance of the castle and this yellow floor there was a gap where three actors appeared, clad in black gowns and white masks, indicating the three main powers that surround and prey on the young characters: church, royalty, and death.

Exploiting the idea of confinement, the set also elaborated on other possible intentions and values, as the design of a porthole on the left side of the main castle entrance that could only be reached by a portable staircase that was not always there. It could serve to remind us of a niche in a chapel: at a certain point we see Ophelia opening it and coming down to the main area. She is therefore related to that sacred—but secluded—place, possibly suggesting a frail young maiden to be sacrificed or sanctified.

Hamlet co-directed by Luís Miguel Cintra and Cristina Reis, with set design by Reis. Photo courtesy of Teatro da Cornucópia.

As for the costumes, these showed an obvious historical influence, proper for such a production, but again, respecting the design as a whole but not seeking to be a lavish reconstruction of “the thing” itself. Indeed, Reis’s design did combine the idea of seclusion and items that pointed to possibilities more in tune with the claim of freedom and love, but scarcely providing what could be expected and desired. We can see that tendency both in the jester’s suit (a lavish design matching the “rich” clown in white and large vest with big buttons) and the costume of the actress that represented a little dog in a furry vest. We could also see suggestions of parody of political and religious powers—in masks and vests—certainly pointing to hidden meanings and showing the glamor and risks in exercising power.

In the expressive significance of this iconic castle invented by Cristina Reis we could see the traces that have marked the long career of this exceptional set designer, who blends geometry with the freedom of the sketch in order to expose the disfiguration of the world. She uses color and the density of matter to set off the light and the unexpected stage detail. Her set design for this performance—that fitted so well both on the broad and deep stage in Almada and the plain room of the Cornucópia theatre in Lisbon, the Teatro do Bairro Alto—showed not only a thorough and inspired reading of Shakespeare’s play, but also a concrete and subtle invention of its symbolic meanings, even when these involve a questioning more than a clear declaration of a definite interpretation.

A further interest was added to the production by the translation by distinguished poet Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen (1919-2004) that was very much in tune with the Shakespearean text itself; blending exquisite poetical formulations and plain straightforward expressions without “forcing” a more scholarly or literal formulation.

is Full Professor of the Faculty of Letters, University of Lisbon (Retired); President of the Portuguese Association of Theatre Critics; and Honorary Secretary of the International Association of Theatre Critics.

European Stages, vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring 2016)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elyse Singer, Managing Editor

Clio Unger, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Hamlet in a Curious Nutshell by Maria Helena Serôdio

- Alvis Hermanis Productions in Latvia and German-Speaking Countries by Edīte Tisheizere

- The Unknown, the Unexpected, and the Uncanny: A New Lorca, Three New Catalan Productions, and a Few Extras by Maria M. Delgado

- 2015 Dance Week Festival and Contemporary Croatian Dance by Mirna Zagar

- Archives, Classics, and Auras: The 2016 Oslo International Festival by Andrew Friedman

- The Stakes for City Theatres: Linus Tunström’s Farewell to the Uppsala Stadsteater by Bryce Lease

- Life is Beautiful? or Optimistically About Bulgarian Theatre? by Kalina Stefanova

- The Multiple Dimensions of the Bulgarian ACT Independent Theatre Festival 2015 by Angelina Georieva

- Theatre in Berlin, Winter 2015 by Steve Earnest

- Musical Theatre in Berlin, Winter 2015 by Steve Earnest

- Gob Squad’s My Square Lady at the Komische Oper by Clio Unger

- New Productions in Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- Manifest for Dialogue: Antisocial by Ion M. Tomuș

- A Fall in France by Heather Jeanne Denyer

- The Iliad as an Oratory: A Warning to a Civilization by Ivan Medenica

- Escaped Alone by Caryl Churchill at the Royal Court Theatre by Rosemary Malague

- Bakkhai at the Almeida Theatre reviewed by Neil Forsyth

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016