The international popularity of the annual Berlin Theatre festival, the Theatertreffen, continues to grow, and so does the demand for the limited number of seats, especially when productions are presented in a small venue, or, in the case of Castorf’s Baal this year, for a single performance. In these cases press tickets are limited to representatives of major German and international publications, and smaller publications (like this one) are placed on waiting lists. Last season only one production was so limited, but this year it was three out of the ten, significantly reducing the possibility of presenting a comprehensive view of the festival. I particularly regretted missing Castorf’s Baal, which stirred up a major scandal when Castorf, as is his custom, layered into the Brecht text a good deal of material from other sources. When the Brecht estate protested, a legal battle ensued, with the result that the production was allowed only two more public performances, one in Munich and the other at the Theatertreffen. The other major disappointment was missing the stage adaptation of the Fassbinder film Warum läuft Herr T. Amok? by the major young director Susanne Kennedy, whose abstract Fegefeuer in Ingolstadt was clearly among the outstanding productions of last year’s festival. The third unavailable offering was Judisth Schalansky’s Atlas der abgelegenen Inseln.

Jelinek’s Die Schutzbefohlenen

Of course, this still left seven evenings of outstanding theatre, clearly well worth the trip to Berlin, not to mention the opportunity to fill in the free evenings with other selections from the always rich theatre offerings of this city. The festival opened with a new work by the German language’s leading contemporary playwright, Elfriede Jelenik, directed by Nicolas Stemann, the director most closely associated with her work. This was Die Schutzbefohlenen, based on Aeschylus’ The Suppliants, and first presented at the Thalia Theater in Hamburg.

The production in many ways reminded me of the stunning Marat/Sade directed by Volker Lösch which came from Hamburg to the Theatertreffen in 2009. Lösch had the ingenious idea of casting the chorus of Marat/Sade from actual homeless street-people in Hamburg, one of Germany’s wealthiest cities, and weaving their actual social testimonies into the structure of the production. Jelenik, as she often does, has created a work out of a major contemporary social crisis, in this case the ongoing Lampedusa protests in Hamburg. This crisis, familiar to most German viewers, has been little reported in the United States, so perhaps a very brief overview is necessary. In 2011, refugees, mostly Pakistani guest workers, fleeing the unrest in Libya, were given shelter in camps on the Italian island of Lampedusa. In 2013 the Italian government closed the camps, gave each refugee a small stipend, and sent them northward to find asylum. Most of them were sent to Hamburg, which provided no support for them and left them stranded on the streets. Protest camps, sit-ins and demonstrations, mostly declared illegal by the authorities followed, but so did support for the refugees, leading to ongoing tensions in the city.

The deaths of another 390 Lampedusan refugees at sea that October added new pressure to the situation. Jelenick, in Hamburg, worked closely with the organizations supporting the refugees, videotaping their stories and developing with the Thalia Theatre there a presentation on their situation which was presented in September of 2013 at the St. Pauli Church, where 80 of the refugees had taken shelter. This essay grew into the full production of Die Schutzbefohlenden, with eight actors and a chorus of twenty-one of the refugees.

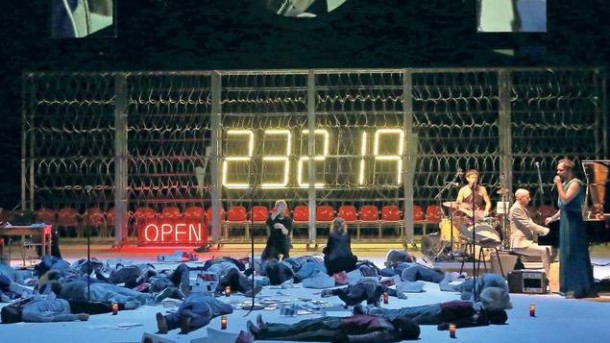

The production opens with the chorus milling about on stage, and out of their babble of voices specific figures appear to articulate their story. In a circular screen at the rear of the stage, appears the head of one of the refugee women, being interviewed. Her image will appear regularly through the evening, reflecting (in English) on the dilemma of her fellows, the loss of families, friends and country, and the frightful experiences undergone before and during their exile.

The text of the play proper begins to be presented by three white male actors in German with English supertitles, a combination of news reports, Biblical references, suggestions of Aeschylus and continuing meditations on legality and illegality. A major theme of the production is touched upon in these opening sequences as the all-male, all-white narrators are challenged by a black man and two women, one black and one white, but these also are Thalia actors. The refugee chorus does not participate in this discussion, although more and more they contribute physically and vocally to the growing sense of entrapment, desperation, and incipient revolt. From time to time they physically dominate the stage, drowning out the more quiet and measured presentations of the professional actors with surges of mass protest, moving downstage, fists aloft, chanting “We are here. We will fight. Freedom of Movement is Everybody’s Right.” This is chanted in English, the language almost universally used by the emigrants. Their dilemma is powerfully presented by their presence, the words of the text, and by strong visual images, most notably a huge barbed-wire wall that is pushed in from the wings and creates a sealed-off camp area upstage. Key repeated terms are “legal” and “illegal” and at one point the chorus personalizes this by directly confronting the audience and pointing to individual members, calling out “legal” or “illegal” clearly at random.

This theme reaches its climax late in the production when we are informed that in fact many of the chorus members do not have legal status and are risking deportation by the very act of this public display. For more than an hour and a half of the two hour plus production, however, material of this sort continues to be repeated, and while the cumulative effect is strong, the repetition begins to weaken it.

Then suddenly the production makes a violent shift and moves into vastly more interesting and challenging territory. The shift is signaled by a striking image, quite unlike anything yet seen this evening. A grotesque female figure with a flowing crown and a flowing blue cape dashes onto the stage mounted upon an equally grotesque black figure of a bull. They circle the performers and disappear as they came—clearly a satiric Europa, whose shocking appearance opens the production in a new direction. The same leading actors attempt to continue their theatrical denunciation of the crisis, but their traditional “engaged” theatre begins to fall apart. Individual refugees tug at their sleeves, begging for attention, only to be ignored and pushed aside. Finally one irritated actor pronounces the key line “We can’t help you; we’re too busy playing you.”

With that shocking articulation, the frame shifts from the depiction of a social crisis to a question of representation itself, of who is speaking in the theatre, what voices are being silenced and at what political cost. As the Hamburg actors maintain their theatrical distance, their presentation becomes increasingly distanced from reality. The men appear in women’s clothing, the black performers in whiteface, and all delivering art songs irrelevant to the situation. Individual chorus members seek to speak out, but are confined to fragments of the texts of others—Aeschylus, the newspapers, Jelenik herself. The singing Hamburg actors attempt to re-establish their authority by displaying a sign: “I an Lampedsan,” but it is scarcely presented before it is turned around to reveal on the reverse side stating “I am Pöseldorf” naming an elegant Hamburg neighborhood which has bitterly opposed the establishment of a shelter for the emigrants within its boundaries. In further expression of this opposition, the image of the black Lampedusan woman so frequently seen in the upstage projection is now replaced by a series of white faces, presumably Hamburg citizens, perhaps actors, opposing the disruptive influence of these “others.” For the first time in the evening, the actors draw a proscenium curtain across this turbulent scene, in a light pastel blue. Upon it is projected a series of images of refugees in boats and the caskets of some of those drowned when these boats capsized, grotesquely decorated with teddy bears, while a recorded voice sings a chilling “Teddy Bear” song composed by Jelinek. The racist comments of the good Hamburg citizens, the horrifying images, the documentary evidence, all continues to add to the indictment of the failure of this city and of the European cultural tradition to respond in an effective way to this ongoing tragedy, but behind all of this demonstration lies the constantly deferred question of who speaks for whom, and to what effect . Even the official program of the Theatertreffen itself lists the names of the eight Hamburg actors, while the names of the twenty-one chorus members disappear behind a neutral three words—”und einem Flüctlingschor” (and a chorus of refugees). The silencing continues.

Palmetshofer’s Die Unverheiratete

Unable to attend the production of the Kennedy piece, I returned several days later to the Theatertreffen to see the first of two productions invited this year from the Burgtheater in Vienna. The selections of the Theatertreffen jury are always looked to as a suggestion what aspects of contemporary German theatre its establishment wants to call attention to, in addition to the presumed high artistic achievement of each entry. Certainly the selection of the first two productions by a new administration at the venerable Burgtheatre places a spotlight on that administrator, Karin Bergmann. Bergmann was appointed interim director, the first woman to hold this position in the 240 year history of the theatre, when Matthias Hartmann left the post amid a major financial scandal. She was so successful in restoring order at the theatre that she was chosen the new director over eighty other candidates, including some of the leading directors of the German stage.

Bergmann’s stated goal is to re-establish the Burgtheater as Europe’s leading theatre institution, and the invitation of her first two productions to the Theatertreffen certainly is an important step toward that goal. It is of equal symbolic importance that these first two major productions under a woman’s administration are both plays that deal with gender issues as well as with a range of issues connected to women’s experience, and both are presented by all-woman casts, a relative rarity in the German theatre.

The first was Die Unverheiratete (The unmarried), written by Ewald Palmetshofer, whose 2007 play Hamlet is Dead. No Gravity gained him wide recognition and the Theater heute prize as the outstanding young author of the year. Unverheiratete in subject matter is very much in the tradition of other major modern Austrian playwrights like Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Bernhard, exposing the willingness of their countrymen to accept the barbarity of the fascists. All of them have used variations of the memory play and the tensions between shifting moral systems in the past and present to address this still painful national heritage.

The three central characters of this drama are a grandmother (Elisabeth Orth), her daughter (Christiane von Pelnitz), and her granddaughter (Stefanie Reinspeger). Although a confusion of remembered detail is an important part of the story, what is clear is that the grandmother in the closing days of the Reich, now sixty years ago, overheard a young Austrian soldier considering desertion. She reported this to the authorities and as a result of her testimony he was executed. When the Nazis departed, the soldier’s father brought the grandmother to trial. She was found guilty and sentenced to prison, where she has remained since and is now an old and broken woman, still trying to determine what is meant by truth and by justice.

Die Unverheiratete by Ewald Palmetshofer. Christiane von Poelnitz (die Mittlere), Stefanie Reinsperger (die Junge), Elisabeth Orth (die Alte). Photo credit: Georg Soulek.

She has left behind her own written account of her story, which has been read by her daughter and granddaughter. The daughter remains obsessed with revenge for her mother’s crime, while the granddaughter, troubled in another way and unable to form any lasting or meaningful human relationships, seeks, in vain, to find out what her grandmother’s motives actually were. There is a general forward movement to the action, beginning with the two younger women visiting the old woman, soon to be released after many years in prison, continuing through her coming home and the lack of closure this provides and ending at last with the suicide of the old woman and the inability of either of the younger women to escape from the cycle of violence and guilt that haunts this house. Indeed, from the beginning the play distinctly echoes the guilt-ridden house of Atreus, with the daughter savagely chopping wood with an ax which urges us to recall the Mycean tragedies.

Such references, not extensive at first, become much more specific in the latter part of the play. The daughter, never able to forgive her mother for the death she caused, specifically cries out, “I am Electra,” shortly before her own daughter, in one of the production’s most violent images, empties a container of blood over her head. In this production there is no avenging Orestes, however, only the smoldering continual sense of justice thwarted and truth never brought to light. The image of Agamemnon’s net is added to that of the ax as the Grandmother finds herself increasingly entangled in a web of knitting she can no longer control. Although the voices of men are often evoked in this all-female action (most notably the judge in the court and the testifying father of the executed soldier), no men actually appear. There is however a chorus of four women, identified as “four sisters” who clearly serve as modern stand-ins for the Furies. They first appear in frilly white dresses with rather foolish hair stylings, but during the production they take on other, and more sinister roles—as a set of identical, almost robot-like caregivers for the aging grandmother, and most chillingly, as a set of ramrod stiff black military garbed interrogators.

Much of the play seems to take place in the shifting memories of the Grandmother, and the ingenious design, created by Robert Borgmann, the director of the production, captures this shifting, indeterminate space beautifully. The opening sequence consists of rapidly shifting, almost cinematographic scenic configurations, with the main stage curtain, an act curtain, and a curtain hung against the back wall rising and falling in different combinations, and the house light and stage lights worked into this shifting pattern, so that actors and audience share a number of different physical and visual relationships in rapid succession. These effects are made more striking by the lighting (designed by Peter Bandl), the most striking feature of which is that the side walls and ceiling are composed entirely of banks of neon lights, which can be blinding in their intensity or offer various gradations, all of which however give to the action a rather cold and sharp-edged feeling. How to deal with the memories of the war, and especially with those long-suppressed, has, as I suggested, been an important theme, especially in Austrian drama, for several decades, but it appeared with particular relevance of May of 2015, when Europe, and especially Germany and Austria, marked with many ceremonies and special exhibitions the 70th anniversary of the ending of the Second World War.

The production I saw the next evening, Common Ground, at the Maxim Gorki Theatre, also dealt with the problem of coming to terms with the aftermath of war, here a much more recent one, the Bosnian conflict of the 1990s. The Gorki, long overshadowed by the Deutsches Theater, the Schaubühne and the Volksbühne, recently achieved new importance with the appointment in 2013 of a new director, the Turkish-born Shermin Langhoff. She established her reputation not only as a theatre artist but a leader of the new “post-migrant” theatre by founding in 2008 the Ballhaus Naunynstrasse which specialized in works by and dealing with the second generation of German-Turkish immigrants. The Ballhaus production of Verrücktes Blut was named Play of the Year by Theater heute in 2010 and was a highlight of the Theatertreffen that year. Langhoff continued this international concern at the Gorki with such success that the Gorki was named Theatre of the Year by German theatre critics in 2014, confirming its arrival among the first rank of Berlin houses. Among the productions that led to this award was Yael Ronen’s Common Ground, subsequently invited to this year’s Theatertreffen. Ronen, who was born in Jerusalem, is best known for a classic work of the post-migrant German theatre, the 2008 Dritte Generation (Third Generation), which brought together Israeli, Israeli/Palestinian, and German actors to explore the continuing tensions between these groups three generations after the Second World War and the founding of Israel.

Yael Ronen and company’s Common Ground

Common Ground applies a somewhat similar approach to the Bosnian conflict, rather less successfully, I thought, but the critical establishment was united in giving it high praise. At the heart of this production was the narration of a bus trip actually taken to the city of Prijedor in the Republika Sprska, the Serbian section of Bosnia. As Ronen was gathering young actors of Yugoslavian descent, she was astonished to come upon two from this same city. The father of one (Mateja Medud) was an overseer in one of the concentration camps which made the city notorious during and after the war, while the father of the other (Jasmina Musić) was a prisoner in this same camp. Three of the other five performers are from former Yugoslavia. Aleksandar Radenković is Serbian, Dejan Bucín is from Belgrade, although, as he explains in a lengthy riff on his family tree, his relatives are located in virtually every part of the region. Vernesa Bergo is from Sarajevo, in Bosnia, and her ties there along with the associations of the First World War inspire a bus stop in that city as well. The other two actors have performed with Ronen before, and in similar parts—the non-German speaking fellow Israeli Orit Nahmias and the native, often played as comic prototypical, German Niels Bormann. Nahmias, who has now been on the professional German stage for two years. is surely the only actress on that stage who, rather proudly, does not speak German, but that is less surprising at the new Gorki, with its calculated internationalism, than it would be almost anywhere else.

In the opening sequence, Nahmias introduces the production in English with supertitles repeating her words above her on either side of the stage. English supertitles are becoming more and more common in major German theatres, but not of course when actors are speaking English as in this case. The ever-critical German Bormann soon interrupts her and demands that she speak German for a German audience, or at least provide German supertitles. This conflict lasts for several minutes and is amusing, even farcical, but except in the most general terms of cultural conflict it really has not much to do with the production. Following this, the supertitles are used in a conventional way, although whoever designed the lighting (not mentioned in the program) apparently did not notice that a large downstage spot entirely obliterated the supertitles on one side of the stage, leaving a good part of the audience “in the dark,” unless they were fluent in both German and English, for the entire latter half of the evening, containing all the key scenes.

The half hour or so after the opening linguistic debate is more relevant, but still, to my mind, not really justified, at least at such length. The case goes through a rapid-fire shouting into the microphone of dozens of world events year by year during the Bosnian crisis—sporting events, political events, natural disasters, trivial human interest stories—supplemented by a whirlwind of visual images in the background. The exhausted audience soon gets the point—that in the overwhelming barrage of news, the Bosnian War was easily swallowed up, except for people, like those in this cast, with particular ties to that region. The point was worth making, but not, I think, at the cost of perhaps a third of the evening.

The bus trip was of course the political and emotional heart of the show, and the description of this experience by the individuals who made the trip, not only gaining new insights into themselves, but more critically, gaining new understanding of each other, was quite moving, with occasional effective moments of humor and equally effective Yugoslavian folk songs, providing a nostalgic grounding for these young people trying to understand a broken heritage.

The at first tentative relationship between the two young women from Prijedor gradually growing into a deep friendship provided an upbeat model for a more hopeful future where the spectres of nationalism would no longer claim victims. The story being a true one gave it a particular resonance on the contemporary German stage, which is equally fascinated by narratives of past and present political, economic, and ethnic injustice and also by performers who have some “real-life” connection to these concerns. A specific term is now often heard in the German theatre for drama dealing with such concerns: Betroffenheitstheater, literally “theatre of dismay,” but perhaps more accurately “theatre of guilt.” In the eyes of a US viewer, the German (and even more the Austrian) passion for such material begins to seem a bit excessive, but on the other hand it would be a pleasant corrective to see a good bit more of such subjects in the generally socially indifferent and historically uninformed theatre of the US.

Panteleev’s Waiting for Godot

After so strong a selection of Betroffenheitstheater, it was something of a relief to move into a very different, albeit no less dark dramatic universe with a new interpretation of Beckett’s classic Waiting for Godot, a co-production of the Deutsches Theater, where I saw it, and the Theater Recklinhausen. The director, Ivan Panteleev, originally from Bulgaria, was much influenced by the late Dimiter Gotscheff, about whom he created an excellent documentary film, and this present production is strongly reminiscent of Gotscheff’s work, notable for its stripped-down simplicity. Indeed there has probably never been a more minimalist production scenically of Godot than this one. There is no tree—only a thin pole stretching upward from the rear of the stage into the flies and bearing a spotlight that at the opening plays across the bare stage like the light in a prison watchtower. That stage, a large tilted surface, contains a large conical depression near its center, suggesting a bomb crater or an indentation in some lunar landscape.

There is nothing else—no shoes, no hats, no vegetables, and for Pozzo and Lucky no ship, no rope, no chair, no baggage. The references to these items remain in the text, but the comic interplay around them is missing, and the actors must play their verbal games in a world that provides them no support whatever, even that of these few properties. They must create their world out of their own bodies and language, which they all most effectively do. One striking element is in fact added to Beckett’s text. At the opening, the stage is covered with a large drop cloth, glowing orange in the strong downlights. After a time of silence, with the upstage spotlight moving back and forth across this surface, the cloth begins to move slowly, drawn into the circular center pit, where it at last disappears, leaving pit and stage an unrelieved black surface. From this pit, now suggesting the navel of this world, emerge first the two tramps Vladimir (Samuel Finzi) and Estragon (Wolfram Koch) and later Pozzo (Christian Grashof) and Lucky (Andres Döhler). All four are familiar figures on the Berlin stage and Finzi and Koch have performed with great success as a comic duo in many productions, including some by Gotscheff, so this production has very strong theatrical associations for most Berlin theatregoers.

The characters, especially Lucky and Pozzo, have less of the comic exaggeration often given them, and seem more sympathetic and human. This is especially the case with Grashof’s Pozzo, who seems more a benevolent corporate manager than a whip-cracking tyrant. Lucky is also more of a simple working class type, who delivers his famous monologue downstage without frenzy but in a powerful and sincere attempt to make its convolutions clear. Döhler also plays the boy with the message from Godot, emerging not from the crater, like the rest, but at the upstage edge of the sloping platform, visible from the waist up and wearing the same costume in which he appeared as Lucky. A minimalist Beckett seems something of a redundancy. Yet this powerful production demonstrates that even the modest physical demands that the text makes can be for the most part eliminated. In the hands of truly gifted actors, especially actors like these with a long experience of ensemble work, such a strategy can even further concentrate the power of Beckett’s dramatic world.

Henkel’s John Gabriel Borkman

On the following evening I attended one of the highlights of the festival, Karen Henkel’s stunning reinterpretation of Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman from the Schauspiel Stuttgart. Henkel is one of today’s best known and most honored German directors, having been invited to the Theatertreffen six times in the past decade, always with striking reinterpretations of classic works—Chekhov, Shakespeare, Hauptmann. One might expect in late capitalist Germany a reading of the play based on Borkman’s financial concerns, but in fact those concerns, and Borkman himself, are here distinctly subordinated to the play’s deep concerns with struggles for power and control, a kind of psychic vampirism.

From the very beginning, we are plunged into a kind of horror film. Instead of the two levels of the Borkman home, the stage, designed by Katherine Nottrodt, suggests a dimly lit subterranean hall, its dark curtains in fact covering only stone walls, its floor a series of rising steps converging, with walls and ceiling, toward a smaller interior stage where at the beginning, the illuminated figure of Borkman lies as if already in his tomb. The rest of the stage is at first in darkness, except for two burning candelabras downstage right and left. Mysterious sounds fill the air, as if in a haunted house—rumblings and crashings (including the reverberating footsteps of Borkman, here not pacing but calculatedly pounding on the floor as a torment to Gunhild below) and mysterious sepulchral music. There is a small organ on the wall to the left, but it is primarily played not by Frida but by Gunhild, mostly music of a religious flavor. There is also a small square opening in the ceiling with a strong white downlight in it, allowing various actors to stand in its glow for particular effect.

Borkman is played by the already corpulent Josef Ostendorf, best known for his comic roles in many of Christoph Marthaler’s productions, and here made even larger, almost too cartoonish proportions, by body padding. In keeping with the production’s shift to the struggle for power and control, however, he is from the beginning quite overshadowed by the two sisters Ella (Lina Beckmann) and Gunhild (Julia Wieninger) and their ongoing conflict. These, in different ways, are as grotesquely exaggerated as Borkman, especially Ella, whom Beckmann portrays in a shambling, disjointed manner as if her body were not properly put together. When she appears in Borkman’s room, however, and recalls their former passion in an apparent attempt to win his support, she manages to twist this awkward body into a series of grotesque imitations of classic seduction poses that reveal in fact an enormous physical control and flexibility and earn her a well-deserved burst of applause.

Wieninger is less extreme physically but equally unattractive, often crouched like a waiting spider and from time to time wielding a hatchet presumably to chop wood, but always threatening something more serious. All three of these central characters carry grotesque rubber face masks which they put on and remove according to the emotional demands of the scene, and these add distinctly to the feeling of watching a rather extreme horror film. Erhart, played by Jan-Peter Kampwirth, is of course the central object of the two sisters’ struggle for control, and the production emphasizes the strategy of each to infantilize the young man. This begins with his arrival, when the two treat him literally as a young child, removing almost all of his clothing (not without considerable sexual suggestion) and pushing him into a bathtub to wash him.

Later, he sits downstage uncomfortably between the two equally unattractive old women, miming having tea with them in considerable discomfort. This domestic truce is not long-lasting however. Soon the two sisters are pulling in opposite directions at the extended sleeves of the sweater Erhart is wearing, pulling him into a suggested crucifixion pose. Similar religious images occur elsewhere—a Pietà and a Mary holding her child—as each sister tries to portray herself as the eternal mother. The effect of all this on Erhart is clear. He appears as totally immature, his repeated desire for freedom hollow and meaningless,and totally under the control of the cold, calculating and emotionless Mrs. Wilton (Kate Strong) who delivers her lines entirely in English. Compared to her, young Frida (Gala Winter) seems quite unsubstantial, drifting about the set almost like a disembodied spirit. Her father Vilhelm Foidal (Matthias Bundshau) provides the most straightforward interpretation of the evening, but even he is drawn into the metatheatrical world being developed by the director when he begins to read his play and we recognize it as the beginning stage directions of John Gabriel Borkman itself. The comments considering whether the story of a comedy, a tragedy, or a mixture of both—clearly in fact intended by Ibsen to suggest the ambiguity of much of his work—is thus made particularly self-referential here.

Like many contemporary German productions of Ibsen and Chekhov, this performance is played without an intermission and runs under two hours, one hour and 45 minutes to be exact. The main shape of the action is unchanged, though Borkman’s part is sharply reduced and most of lines of the last act replaced by pantomime. The major alterations begin with the departure of Erhart, who is angrily rejected by Gunhild and also (contrary to Ibsen) by Ella. Erhart then seeks to bid farewell to Borkman, collapsed on a bed half-way up the stage, but his father can emit only choked mutterings. He has no further lines in the play. The sisters go up to him, hear his final subdued cries, and then set up a screen in front of his silent body. At this point Foidal enters, to present his last scene about being run over by the sleigh, but the sisters prevent him from seeing Borkman’s lifeless body.

After Foidal leaves, they laboriously labor together to roll his ponderous bulk upstage to the bed/bier in the alcove where we first saw him. When he is stretched out there, they briefly stand at his head and feet without speaking. Due to the slanting roof, when they are standing in this inner stage we can see only the bottom half of their bodies. Then they bend over together, direct broad smiles out at the audience, and move downstage hand in hand, as if to accept curtain calls. The audience welcomes them with enthusiastic applause, but Henkel has one final trick to play. The sisters speak for the first time since Foidal left. “My applause” cries one, and “MY applause” responds the other. The lights go out as they begin flailing at each other and come back on to find them leading the actual curtain calls, which are enthusiastic and extended.

Rüping’s Celebration

The following evening a stage adaptation of the well-known Vinterberg and Rukov film Celebration (Das Fest), which has been adapted for the German stage in over fifteen versions so far this century. This was the first Theatertreffen invitation for the young director Christopher Rüping, who has been working as a freelance director since 2011. This was his first commission at the Schauspiel Stuttgart. His approach was a highly distinctive one. Many stage adaptations of this work, like the London production a decade ago which toured to New York, follow the lead of the film and give the work a fairly naturalistic interpretation, but in Germany, where conventional naturalism is not nearly so popular as in the Anglo-Saxon world, the naturalistic approach of the film is often replaced by various much more consciously theatrical approaches. This is certainly the case with Rüping’s interpretation. The seven young actors Rüping utilizes have taken the text as inspiration for a series of improvisations very much suggesting a better than average experimental student production of the 1960s. The result is an energetic, imaginative, and colorful evening which engages and entertains but which rarely engages with the seriousness or darkness of the central concern of the play, which is child abuse within a family which is known to all but never (until this fateful evening) spoken of. There are plenty of visual clues to this situation. The intertwined complicity of the family is ingeniously suggested by each of the characters donning, over their basic grey full-body exercise suits (costumes by Lene Schwind), large colorful sweaters, with the first letter of the names of the three children, with O’s for the two almost senile grandparents, and with PA and MA for the parents. These markers are frequently exchanged, however, so that Paul Grill, for example, who begins wearing the C sweater and assuming the character of the son Christian, soon exchanges that sweater for that of PA, his antagonist and abuser, and in the course of the evening, takes on other roles, marked by sweaters, both male and female.

The ongoing cover-up of the family’s dark secret by a veneer of happy relationships is suggested by rains of confetti, which shower down on this “celebration” periodically throughout the evening. The table at which the family gathers for the event is here broken up (like the story itself) into a multiplicity of smaller tables, which are scattered all over the stage as if it were some sort of furniture warehouse and which are used, in the manner of improvised theatre, to provide platforms and props whenever the actors wish to employ them. Indeed at one point a number of them are put together across the stage and covered with a long white cloth to suggest the family dining table of the original story, but an onstage wind machine, often used to blow confetti, snow, and fragments of paper across the stage, soon blows away the cloth and the actors break the table apart. In one striking image near the end, the actor with the PA sweater builds a pyramid of tables at the rear of the stage and attempts to take command of the production from that vantage point, but his authority is already collapsing and this attempt fails. Much more effective and striking is the appearance soon after of a totally nude actor downstage center, his body covered with nothing but whatever still-falling confetti clings to him. Without a sweater, we cannot tell which of the victims he represents, but his exposure powerfully expresses the exposure and the shame of the long-hidden secret.

This is, alas, one of the few moments when the dark side of the play and its corrupting hidden eroticism is suggested. The overall impression is much more one of an exuberant theatrical meditation upon the inter-relationships within a troubled, but not deeply or darkly troubled family. The subject is a serious one, but the young actors are clearly having so much fun presenting it that it is hard to become in any way emotionally involved. The aura of improvisation is underlined at the very beginning when as actor presents the audience with a green and a yellow script, presumably containing different versions of the story, and invites the audience to choose. The “winning” text is then referred to fairly openly for the next several minutes and gradually left aside once the production is under way. Whether a different version in fact exists is not clear, although one might speculate that it might be one which, without sacrificing the energy and imagination of this company, would be more successful in conveying the more serious and dark side of this family history.

Lotz’ Die lächerliche Finsternis

The final Theatertreffen production I saw was the second from the Vienna Burgtheater. This was Die lächerliche Finsternis (The Ridiculous Darkness) by Wolfram Lotz. It was one of the most produced new plays in the German language last year, being offered in eight different theatres. The version here was the original one, created by the noted Czech director Dušan David Pařízek and was stunningly presented by four young actresses from the Akademietheater who played a wide variety of roles, both male and female. The play was first conceived as a radio play (Hörspiel), a form far more popular in Germany than in the English-speaking world, and this orientation is especially clear in the prologue, which presents an autobiographical testimony/defense of a Somali pirate (Stefanie Reinsperger) brought before a court in Hamburg. This monologue sets the tone of the evening by being at the same time a biting critique of late capitalism (the pirate is driven to piracy because international corporations have destroyed his fishing fields), and a free-wheeling parody/compilation of Western clichés about the world they both fear and exploit. Thus when the Somali is unable to pursue his dream of becoming a fisherman, he decides to attain a diploma from the “Advanced School of Piracy in Mogadischu” supported by a variety of grants from Islamic societies and international organizations for the development of East Africa. His actual career is piracy is a series of confusions and failures and his trial a ridiculous farce. “This is only a text!” cries the pirate in one of many metatheatrical asides, “a harmless theatre text! It must not be confused with what is happening in reality.” But of course that confusion, and the confusion of reality itself is what the play is all about. The fact that this male character is played by a woman who, though obviously a white blond, introduces herself as a “black Negro from Somalia” lets the audience know at once that this production is going to tackle not only political matters but also those of race and gender. Both stereotypes are challenged throughout and the ongoing German theatrical uneasiness with blackfacing continually suggested in the second part, as the white characters become more and more smeared with black makeup as they travel upriver into the “ridiculous darkness.”

Die lächerliche Finsternis (The Ridiculous Darkness) directed by Dušan David Pařízek. Photo credit: APA/Georg Hochmuth.

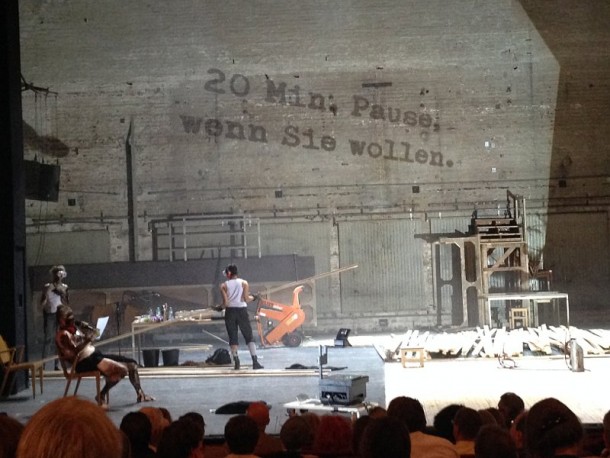

This prologue establishes a variety of themes that will be developed in the main body of the play, which is an extended parodic retelling of an amalgam of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Between these two sections, however, comes an interval, which is one of the most innovative parts of this highly unconventional production. During the first section, the monologue of the Somali pirate was given against a neutral background made up of multiple long thin slats, each perhaps ten to twelve feet high, placed side by side to form a neutral wooden screen. When the jungle river journey is ready to begin, one of the actors pushes against the screen, which collapses in a great clatter. The four actors begin a hypnotic rendering of the popular African-based chant which has become an aural icon for that continent in the West: “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” As the song continues, the actors turn on a large wood shredding machine upstage and begin to feed one by one sections of the screen into it, literally deconstructing the theatrical space of the prologue and opening the stage into an unbounded world of their own imaginations and a dense layering of literary, filmic, theatrical, and political references. From here onward the actors create their own bizarre universe, composing for example the almost incessant cries, rumblings, and mysterious noises of the jungle from a table full of various noisemakers that those who are not in a scene manipulate upstage. The combination of song and physical action, a performance in its own right, is announced to the audience as “an intermission if you want one.” It lasts twenty minutes and indeed some audience members move out into the lobbies, while many remain, treating this sequence as part of the performance.

Just as Coppola moved Conrad’s realm of the threatening “other” from Africa to Vietnam, Lot has relocated his action to a clearly imaginary jungle river in the “Hindu Kush” of Afghanistan, retaining all the exotic clichés of those previous works, but layering onto them a free-ranging selection of current cultural references. In this retelling two German soldiers travel by boat into the jungle in search of a renegade third who has reportedly gone mad and killed some of his fellows. The two are a typical pair of male adventurers, the hard-bitten experienced Indiana Jones sort of veteran adventurer who narrates the story and the enthusiastic but green recruit, with a more positive but more naïve world view. From the beginning however these traditional roles are undercut because they are played by women parodying these male stereotypes (Cartrin Striebeck playing the tough Sergeant Oliver Pellner with an obviously glued-on mustache and Frida-Lovisa Hamann portraying his naïve companion, Sergeant Stefan Dorsch).

Intermission. Die lächerliche Finsternis (The Ridiculous Darkness) directed by Dušan David Pařízek. Photo credit: APA/Georg Hochmuth.

The other two actors, Reinsperger and Catrin Striebeck, play a variety of characters, men, women, even a verbose parrot, that the adventurers meet on their trip upriver. These encounters allow them to experience various examples of real and fantasy activities in the nightmare world of the “Hindu Kush.” Thus an Italian officer at a military enclave in Afghanistan expresses his disgust at the surrounding natives who pee standing up and eat food which he describes in nauseating detail until we realize he is in fact talking about traditional German dishes like blood sausages, a Serbian trader describes in almost unbearable detail the death of his family in a NATO bombing only in order to elicit sympathy so that he can sell goods to the travelers, and a missionary who has saved a village from the godless belief of Islam so that, as good Christians, they can more openly express their sexuality and work productively harvesting Coltan (actually a product of the Congo) for use by the computer industry. At the end of the evening the morally indifferent Pellner fulfills his mission and provides the coordinates for the continued destruction of the “enemy,” leaving Dorsh and Deutinger, the agent they were originally ent to find, to puzzle over the meaning of all this suffering and destruction, and finding no really helpful frame of reference.

There has been some negative reaction to the piece by those who find its mixing, as its title makes clear, of almost slapstick comedy with some of the darkest material in the contemporary world, but I found this precisely its appeal, and in the best tradition of dark satire, that of Swift and Voltaire. It seemed also fitting that my Theatertreffen experiences this year began and ended with plays dealing with the fear of Europeans about the non-European other. The shadow of the ongoing refugee problem hung over the entire festival. After almost every performance a member of the cast asked the public to support various groups involved with reacting to this ongoing problem, and one could find more material available at stands set up in the lobby. Probably no social question more concerns the German public at the present than this one, and since the Germans commendably traditionally look to the theatre as a forum for the discussion of important public issues, it was not at all surprising to find so many and such clear examples of that tradition at work in this year’s Theatertreffen.

Marvin Carlson, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is The Theatres of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia with Khalid Amine (Palgrave, 2012).

European Stages, vol. 5, no. 1 (Fall 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elyse Singer, Managing Editor

Clio Unger, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Avignon the 69th Festival, July 4 to 25, 2015: Discovery Beyond The Classics by Philippa Wehle

- The 2015 Oslo International Festival at Black Box Theatre by Andrew Friedman

- The 2015 Theatertreffen by Marvin Carlson

- A Feminist Tuberculosis Melodrama: Melek by Theatre Painted Bird by Emre Erdem

- Nachtasyl at the Berliner Schaubühne: A Radical View of Gorky’s The Lower Depths by Beate Hein Bennett

- From Spectacular to Minimalist: Four Plays in Madrid, April 2015 by Phyllis Zatlin

- European productions at Montreal’s Transamériques Festival 2015 by Philippa Wehle

- Childish or Adult? Recent productions in Germany by Roy Kift

- Russian Drama in Finland by Pirkko Koski

- Troubling Cross-Currents in the Budapest National Theatre by Marvin Carlson

- Spain: Engaging with la Crisis Through Theatre by Maria Delgado

- Life and Death in the Emergency Room: Linus Tunström’s Faust 1 at the Staatsschauspiel Dresden by Bryce Lease

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016