Montreal’s Festival Transamériques has a new director, Martin Faucher, actor, director, teacher, administrator and artistic consultant to the festival since 2006. For his first festival, his program choices in dance and theater proved to be every bit as exciting and inviting as in previous festivals.

Passim by the Théâtre du Radeau/François Tanguy from France, offered an opportunity to be bathed in a flood of words written by Shakespeare, Molière, Virginia Woolf, Flaubert, Calderón and many other literary greats, spoken in different languages by a stellar team of actors who play many roles. “Passim,” a Latin term meaning a word or passage repeated here and there throughout a written piece, is an apt title for this fascinating work composed of excerpts from poems, tragedies, and stories in which key words and themes seem to echo throughout the hour and forty-five minutes.

Tanguy invites his audiences to immerse themselves in a dreamscape of shadows and dark shapes, tableaux vivants, and figures dramatically changing roles. Some are familiar legends; others are mysterious personages. With scenes and images from King Lear, Orlando Furioso, The Trojans, and The Misanthrope, accompanied by Beethoven, John Cage, and Rachmaninov, he leads us through a “melancholic bacchanale” to quote the young authors of Médusine, a new fanzine found in festival theaters that offered fresh insight into this year’s program choices.

Rustic wooden tables of varying sizes fill the stage, metallic frames hang over the tables or stand askew here and there. There seems to be little room for actors to come and go yet they do, lifting the tables, rearranging the set, and moving panels back and forth to open up spaces and close down others, creating a set that constantly moves. As the play begins, a woman steps out of a darkened frame as if from a painting. “Look!” she cries. “In line with the ridge…Doesn’t it look like a head appearing? A helmeted head?” The lines are from von Kleist’s Penthesilea, the story of the queen of the Amazons who kills Achilles. She delivers her lines in French rather than German. Other literary excerpts in Passim are in Italian and others in Spanish. Understanding the words seems of less concern than receiving the forcefulness of the images as they move in and out. As Tanguy says, these are “vocables” or meaningful sounds rather than texts. Interestingly, a handout containing these excerpts is given to the audience as they leave the theatre.

Radeau’s actors play peasants as well as masters, servants, queens and kings. They quickly put on sumptuous costumes or don masks and wigs before one can catch one’s breath. They dance the waltz or cavort wildly, jumping off tables and whisking their fellow characters off to another area on the stage. In a quieter moment, out of the shadows appears a man on a makeshift horse put together by actors hiding under a blanket. Wearing a tall cardboard crown or helmet, he is a melancholic figure, perhaps don Quixote the chivalric hero chasing windmills, or one of the kings from Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, when he takes his crown off and delivers a few familiar words. Later a jolly group gathers on a red sofa clearly having fun playing out a scene reminiscent of a Marx Brothers film.

Among these many striking pictures, the scene from King Lear affected me the most. Lear has just spoken with his daughters Regan and Goneril and given them their share of his estate. It is now Cordelia’s turn—Cordelia, his most beloved daughter. She has been sitting at a table staring into space, steeling herself perhaps for what she must say to her father. As her sisters, their husbands, and entourage fade into the background in slow motion, Lear eagerly swoops over to the table where Cordelia sits motionless, waiting her turn. Smiling with delight and anticipation, Lear sits next to her, takes her hand in his, and speaks the famous lines: “Now, our joy…what can you say…Speak.” Cordelia’s response is well known as is Lear’s. Played in close-up, Lear’s condemnation of the daughter he loved most, is especially devastating. “Thou my sometime daughter…Hence, and avoid my sight.” In vain, Cordelia’s arms reach out to him and we are left with a haunting image of Lear’s most faithful daughter collapsed on the floor. Passim is truly a “beautiful shambles,” to quote the festival program.

In an entirely different vein, Tauberbach or Deaf Bach, a fusion of theatre and dance, by the well-known Flemish artist Alain Platel and his company Les ballets C de la B, is a hymn in praise of beauty in the midst of squalor. Platel was inspired by Estamira, a 2004 documentary by Marcos Prado about a woman who chose to live in a dump in the middle of a Brazilian favela. To deliver her story, Platel favors a soundscape comprised of Polish composer Artur Żmijewski‘s Bach music sung by deaf people along with other excerpts from Bach and Mozart.

The show opens on a stage overflowing with mounds of old clothes and colorful rags. Two lighting rigs hang overhead. Five dancers emerge out of the scattered detritus as if born of the filth and decay of a city’s waste. They dive back down into the piles, roll around in the muck, and come up again, enjoying the novelty of their newfound home, even though flies are buzzing and one can only imagine the bugs and other creatures living among them. Enter Estamira, forcefully played by Dutch actress Elsie de Brauw. She plows through the garbage heap with determination, picking up old soiled clothes and sundry used items of someone else’s life, as she begins an extended monologue composed of her delusions and obsessions but also her very real desire to make positive changes in her new environment. Even though the dump is toxic—performers cough and sneeze and throw up—she claims that she likes it and is happy there. She wants to bring order to this chaotic gathering of men and women in various stages of dress and undress who cavort before her, inviting her to join them in their Dionysian revel. She resists at first even though they kick and beat her and carry her off in a wheelbarrow, tempting her to give in.

Platel’s dancers are outstanding as always with their riveting physicality and fascinating quirky/jerky movements, their “bastard dance,” in Platel’s words, “extreme movements expressing pain.” With them, it is all fun and games, simulating sex or hanging from the lighting rigs until they drop. Estamira tries to convince them that they should pay attention to what they have to be grateful for in life. She wants peace and an end to suffering, she tells them, as a recorded voice shouts abuse at her, trying to deter her from her mission. Even though there is little food, Estamira decides to prepare a “fantastic spaghetti,” convinced that “we eat better here than in any restaurant.” Clearly she has decided to stay in the dump and join the strange creatures living there. She will dance with them. The show closes as the six performers gather to sing “Soave sia il vento” from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. May the wind be gentle, and the waves calm for these marginal souls.

Platel’s Tauberbach, part theater part dance, investigates themes of exclusion and difference, through the lives of marginal people living in extreme conditions and how they manage to survive. The piece “reflects our hyper-consumerism and the exclusion of the damaged and the dispossessed, ” he told an interviewer in Montreal, “but also the idea that it is possible to view the world differently and to find better ways of living together.” (See also the report on this production in the Theatertreffen essay in ES, volume 2)

Portuguese playwright, actor, director, and newly appointed director of Portugal’s national theater, Tiago Rodrigues, left a lasting impression on those who were fortunate enough to see his remarkable By Heart, “performed” by Tiago himself along with ten members of his audience. The inspiration for this play was a request made to Rodrigues by his grandmother who loved to read but realized that she was losing her sight and wanted Rodrigues to choose a book for her that she could learn by heart before going blind. In searching for a book for his grandmother, he collected other stories and anecdotes. His research included readings on the transmission of knowledge and the importance of learning by heart. He finally decided on a book of Shakespeare’s sonnets, seven of which she committed to memory before going blind.

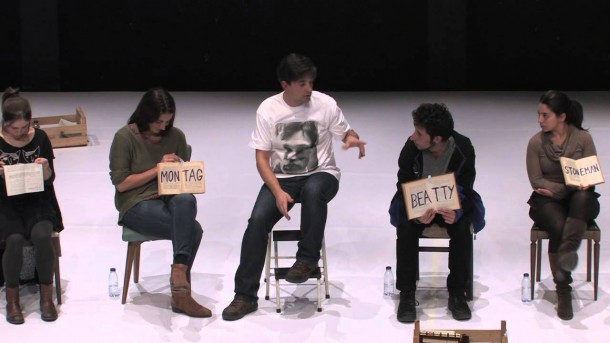

The stage is empty but for ten straight backed chairs lined up in a row with a stool in the middle. Crates of books lie on the floor. Wearing a T-shirt with an image of Boris Pasternak in front and George Steiner in back, Tiago invites ten volunteers to join him on stage where they will learn a short text by heart with his guidance. The text he has chosen is Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30: verses that speak of lost love and memory. Bottles of mineral water await the ten eager but somewhat nervous volunteers. Rodrigues begins with a short story of his grandmother whom he would visit in her village, bringing her crates filled with olive oil, sausages, cheese, and other staples. One day he brought her crates of books (he points to the crates on the stage). Before we learn more about his grandmother, Rodrigues turns to memories of a television show he once saw entitled Beauty and Consolation. It featured an interview with George Steiner, which so obsessed Tiago that he learned it by heart. As he tells the story he hands an open book to one of the volunteers. It contains a large sign with the name George Steiner. Steiner told the story of Boris Pasternak who when he attended the Soviet Writers Congress in 1937, was warned by his friends not to speak. Rodrigues hands a sign with Boris Pasternak’s name on it to the participant sitting next to him. Pasternak stood up nonetheless, he continues, and pronounced the number, “Thirty.” Two thousand people stood up and recited Shakespeare’s sonnet by heart. This is Rodrigues’s introduction to the poem he is about to teach the volunteers. He recites the sonnet by heart. The ten volunteers recite after him, timidly at first and gradually with more confidence. In between stories, he returns to his learners and gently coaches them verse-by-verse.

Among the books in one of the crates is Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. Rodrigues takes it out and begins to tell the story of Montag, the fireman who is supposed to burn books but changes his mind. As he talks, he hands out more signs to the participants: Montag, to a woman on his left; Beatty, the fire chief, to another participant; and Velha Senorha to a person on the far end. He walks around and behind the participants, animatedly telling the plot and quoting directly from the book as he addresses them as the different characters.

Rodrigues is not only an engaging storyteller, he is a consummate teacher as well. He puts his learners at ease, telling them: “If you sometimes forget a word, it’s not a problem.” Towards the end of his class, he tells the newly confident students that he has a surprise for them. “We are going to eat Shakespeare together.” He has had a local pastry shop make wafers with the verses they have been learning written on them. As they eat and digest the words they have so carefully memorized, Rodrigues returns to his grandmother Candida. One day, he decided to take ten people to her retirement home in the hopes that Candida will teach them a sonnet. She is 94 and does not recognize the visitors surrounding her but she manages to summon the strength to recite Shakespeare’s sonnet for them. By Heart ends with the volunteers reciting the sonnet from memory followed by Tiago reciting it in Portuguese.

Rodrigues leaves us with a lasting impression of the value of memorizing as a gesture of resistance. What we have committed to memory, he tells us, remains with us forever. His heroes clearly stood up to censorship and oppression. So must we. As Steiner said in Beauty and Consolation, and Rodrigues quotes: “Once ten people know a poem by heart, there’s nothing the KGB, the CIA, or the Gestapo can do about it. The poem will survive.”

By Heart is theatre that is reinvented on the spot. The basic text does not change but the ten participants bring their different personalities and reactions to the experience so that there is always an element of the unpredictable. What matters most to Rodrigues is the chance to be together with people for awhile to break down the barriers between audience and play. (This section on By Heart is part of an article about the work of Tiago Rodrigues written for TheatreForum.)

Philippa Wehle is Professor Emerita of French Language and Culture and Drama Studies at Purchase College, State University of New York. She writes widely on contemporary theatre and performance and is the author of Le Théâtre populaire selon Jean Vilar, Drama Contemporary: France and Act French: Contemporary Plays from France. She is a well-known translator of contemporary plays with a specialty in creating supertitles in French for emerging theatre companies. Dr. Wehle is a Chevalier in the Order of Arts and Letters.

European Stages, vol. 5, no. 1 (Fall 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elyse Singer, Managing Editor

Clio Unger, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Avignon the 69th Festival, July 4 to 25, 2015: Discovery Beyond The Classics by Philippa Wehle

- The 2015 Oslo International Festival at Black Box Theatre by Andrew Friedman

- The 2015 Theatertreffen by Marvin Carlson

- A Feminist Tuberculosis Melodrama: Melek by Theatre Painted Bird by Emre Erdem

- Nachtasyl at the Berliner Schaubühne: A Radical View of Gorky’s The Lower Depths by Beate Hein Bennett

- From Spectacular to Minimalist: Four Plays in Madrid, April 2015 by Phyllis Zatlin

- European productions at Montreal’s Transamériques Festival 2015 by Philippa Wehle

- Childish or Adult? Recent productions in Germany by Roy Kift

- Russian Drama in Finland by Pirkko Koski

- Troubling Cross-Currents in the Budapest National Theatre by Marvin Carlson

- Spain: Engaging with la Crisis Through Theatre by Maria Delgado

- Life and Death in the Emergency Room: Linus Tunström’s Faust 1 at the Staatsschauspiel Dresden by Bryce Lease

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016