Pornography, perhaps the best known novel by the Polish author Witold Gombrowicz, has been freed from the pages of the book and has been “re-written” for one of the most famous Italian stages, thanks to an extraordinary operation of dramaturgy and direction by Luca Ronconi. The show was a co-production of the Theater Center Santacristina and the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, which is directed by Ronconi, in collaboration with the Spoleto Festival. Pornography was the subject of a summer workshop at Santacristina in 2012, was tried out as a reading, then staged in 2013 in the rehearsal room at the Piccolo in Milan, and then presented to the public in previews in the beautiful Umbrian town of Bevagna, at the 56th Theatre Festival of Spoleto. Finally, it was added to the repertoire in its final form at the Piccolo in Milan in the 2013-2014 season. Last spring I had the opportunity to see the production at the Teatro Argentina in Rome.

The show is therefore the result of a long dramaturgic and directorial work, of two years of study and preparation. It was born in a workshop experience, in the open yard of Santacristina, where for many years Ronconi has been working with experienced professional actors, as well as with young people from the most important Italian theatre schools. Santacristina is also the countryside home of the director, a space of experimentation and research where Ronconi cultivates his students with the best care and attention, as the plants in his garden. It is a laboratory space, which is unique in the Italian theatre, where young actors can interact with the leading figures of the Italian stage. Discussing this production therefore means telling the story of a project carried out at different times and in different spaces. The workshop was born and raised in the quiet of the Umbrian countryside and from it developed a show staged in the theatres of the major Italian cities.

The novel effect

Ronconi’s reading of and passion for Gobrowicz’s works go back a long way. The director himself has revealed the reasons which led him to stage Pornography: “I still have a lively memory of my first readings of Gombrowicz, dating back to the sixties: Pornography, but also the comedies Ivona, Princess of Burgundy and Marriage, the novels Bacacay and Kosmos [ . . . ] I like his caustic wit, irreverence and intelligence. I appreciate the caustic spirit as it works itself out — this is especially evident in Pornography — in the life of a culture.”

Witold Gombrowicz, who lived between 1904 and 1969, is considered one of the greatest Polish writers of the twentieth century. His work, influenced by that of his friend Witkiewicz, was characterized by a continual satire against society, giving rise to a grotesque vision of reality. Its main themes are related to the comic tradition of Rabelais and Cervantes. Gobrowicz was a Polish émigré in Argentina during the Second World War, fleeing the Nazi occupation and later the communist regime. In a book published in Argentina in 1960, three years before his final return to Europe, Gombrowicz wrote: “Pornography is a sensually metaphysical novel” (Gombrowicz, 1960/1994). The work unfolds through a series of “oppositions” that are at the basis of his literary work. Among the braided “oppositions” in Gombrowicz’s work are those between old age and youth, wealth and poverty, urban and rural societies, male and female, fidelity and betrayal, faith and atheism.

In his “secret diary,” Kronos, the author states that he began writing Pornography in June 1955 and completed it in February 1958, after several pauses and reflections. In an interview in 1969, conducted by Dominique de Roux, he summarizes its plot. The play takes place in a period of war and is set in a country house, during the Nazi occupation of Poland. Two gentlemen of a certain age encounter a pair of teenagers who they feel should be violently attracted to each other by a mutual sex-appeal. The young people, however, do not seem to be aware of their situation. This irritates the two gentlemen, who would like to see all that beauty realized, to break open the young people’s poetic side. They attempt to wake up the boy and the girl, to get them to love one another, to throw them into each other’s arms. Gradually the two men, fascinated by the beauty of youth, themselves fall in love with the couple. They want at all costs to penetrate their charm and bind themselves to the youngsters. They decide that a crime, a sin committed with them, can allow them to creep into that otherwise impenetrable intimacy. So they organize a murder in common. The seduction therefore becomes indirect, following the devious course of the murder, but that does not take place as planned and the victims turn out to be more numerous than expected.

Behind the prevaricating intention of the two elderly men, Frederick and Witold (actually two sides of the same person, playing with the feelings and desires of two teenagers, Henrietta and Charles), in Pornography there is a tangle of interwoven but disparate elements: generational conflict, tension between the senses and intellect, boredom and lust for dominion, hints of homosexuality and metaphysical overtones.

The Polish writer once wrote that he did not believe in a philosophy of the non-erotic, and distrusted asexual thought. Even perverse impulses could be refined and transformed into literature. Yet, this story has very little which could be considered pornographic in the literal sense, even though in the center of the story there are mysteries of desire and feeling. The title, therefore, can be deceiving: it appears justified by the desire that becomes gradually more and more anxious in the two protagonists. They try to encourage, with various tricks and stratagems, an intimate encounter between two young people who do not really show any mutual sexual attraction.

Ronconi has himself explained that the novel, despite the title, is not in fact pornographic. “The problem here is just the opposite, namely that between the two young Charles and Henrietta nothing ‘physical’ happens, and it is this that gives no peace to the two protagonists Witold and Frederick, who do not understand how two young people with beauty and sensuality can be together, yet remain totally indifferent to each other. Hence, the idea of concocting something that can push them in each other’s arms.” He continues: “Pornography hides a corrosive view of the pillars of Western culture: God, country and art (…) The title is meant to be provocative; it evokes a ‘physical’ content that is not really in the text, but refers only to the imagination of two older men in relation to two youths, their young age, their beauty and sensuality.”

If pornography is taken in the literal sense, as a discussion or representation of obscene images and material, created to erotically stimulate the reader or viewer, then this story is far from being pornographic. Here the Top of Formterm should be understood in the context of the the capacity to watch. It refers to the idea of looking at something that you should not see. The novel was in fact initially titled Actaeon, after the hunter in Greek mythology who, having seen the naked Diana bathing with her nymphs in the woods, was turned into a deer (and then torn to pieces by his dogs). Gombrowitcz had in fact, as he wrote the novel, a postcard with a reproduction of the famous painting The Death of Actaeon by Titian on his desk (cf. Cataluccio, Pornografia e la bellezza compromettente dell’immaturità, 2014, p. 16).

Pornography is a text dealing with the obsession and tragedy of watching, an action that causes misunderstandings, pleasure and pain at the same time. In this regard, Ronconi advised his actors that “Pain is the third dimension of the text, along with space and time. These are three dimensions, not two dimensions and a feeling.” The novel is a continuous reflection on the act of watching, observing, and spying upon the lives of others: it is a masochistic and painful “red thread” of voyeurism. Ronconi has said that the fulcrum upon which the play is built is the look. We look at two voyeurs looking at two young people who are not looking. Again in the words of the director, we can read the story of Pornography as “two voyeurs watching a possible youth.” The scene of voyeurism of the two protagonists, Frederick and Witold, thus becomes one of the main keys of interpretation (and represents the turning point of the novel as well as Ronconi’s stage version). This is the basis of the final tragedy, which is also the result of a mise-en-scène. Gombrowitcz himself stated that Frederick is actually more a director than a voyeur, with something of the chemist, who combines people with each other, seeking to distill from them a new intoxicating beverage.

The allusions to a homosexual relationship between two elderly protagonists should also be read in this light. Attracted by the beauty and innocent freshness of the young people, they create an absurd series of situations of seduction that are built upon the relationship between Charles and Henrietta. Witold is the author’s alter ego in the novel, in fact he even bears the same name. In the show, one might say that he is also Ronconi’d alter ego, especially if one considers the striking resemblance of the director to Riccardo Bin, the actor who plays the role. Witold and Federico seem to stage a theater of romantic intrigue, because they are in love—but not so much in love with the two young people as with their youth.

Youth was for Gombrowicz synonymous with cruelty, irresponsibility, inaccessibility, imperfection, and inferiority, as opposed to the fullness and maturity of adults. Nevertheless , the writer observed that all men, condemned to a mediocre and embryonic existence, tend to recall that very first stage of life as moving on a more animalistic and instinctive level of attraction. The eroticism experienced close to death is not love, but something more intimate, not carnal. It is rather a chilling look, like the old bigot who lays eyes on Frederick and dies, or like the looks of the two murderers who cannot but scrutinize the bottom of their disaster.

The theme of generational conflict between maturity and immaturity is central. In his 1960 Diary, Gombrowicz explained: “The world is written for two voices. Youth completes the Fullness with its lack of Fullness; this is its ingenious mission: the theme of Pornography. I consider it as one of my main tasks, both aesthetic and spiritual, to find an approach to youth which is more rigorous and dramatic than what is currently in vogue. To push it towards maturity (that is, reveal its relationship with maturity). (…) As you know, man seeks the Absolute and Completeness: absolute truth, God, maturity, and so on. To embrace all things, to fully realize his own development; this is his imperative. Well, Pornography manifests another human aspiration, more hidden and less obvious: his need of incompleteness, imperfection, inferiority, of Youth”. (Gombrowicz, Diary, 1960/2008, VII-VIII)

Mimesis and diegesis in scene

With the novel and the play Pornography, Gombrowicz and Ronconi (supported by a cast of amazing actors) seem to offer a confession, partly autobiographical, an “intimate diary” without shame. The director turns the novel into a macabre comedy that, with four murders in the plot, is also tinged with tragedy, but without ever falling into the melodramatic. Viewers followed the three-hour show as if they were witnessing a surgery: a deafening silence reigned in the hall.

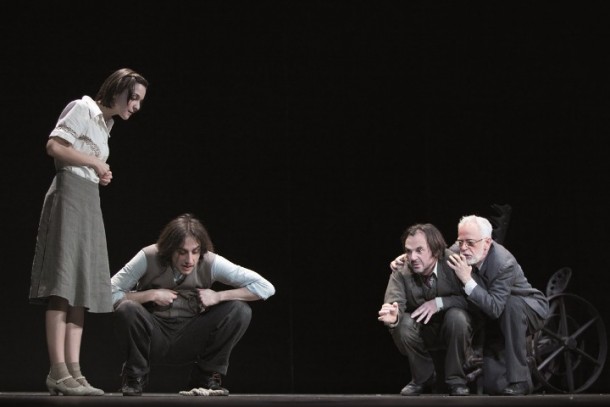

As mentioned earlier, Ronconi chose to represent the text in its entirety, without altering the form of the novel. The curtain rises on a grim living-room in dark and distressing colors. The first scene shows the almost lifeless bodies of the two intellectuals, sitting next to one another. They argue about the proletariat, religion, art, literature. Federico has an outburst completely alien to this environment. The writer Witold is attracted to the man. The two begin to work together, travelling, sharing their lives and engaging in a deadly relationship, where the unthinkable becomes thinkable and feasible, the maturity of some and the immaturity of others will be resolved in a series of crimes. Bathed by the light of Pamela Cantatore in an alternation of light and darkness, the two exceptional protagonists — Riccardo Bini in the part of Witold and Paolo Pierobon, who plays the destructive Federico—are the focal point of a show, where the anxiety can turn into irony, harshness into a smile.

A number of young actors appear alongside these protagonists. Ronconi has stated that “Pierobon and Bini, the protagonists, are experienced actors. The young people make pleasant and interesting appearances, but they serve rather as the net at which you throw the ball . . . and they are very good in this respect.” Everyone does well: from Nani Michele, Franca Penone, Valentina Picello and Ivan Alovisio to Francesco Rossini, Jacopo Crovella, Lucia Marinsalta and Loris Fabiani. They represent that not entirely innocent youth, the appraisal of which, according to Gombrowicz, cannot and should not ignore the erotic.

The empty stage reveals much more than what it shows: the icy, remote black box devised by Marco Rossi seems to evoke one of the disturbing works by Donald Judd. The action passes from people to objects. In the scene lined with black but iridescent panels, the meager furniture runs on hidden tracks (a device dear to the director and seen in many of his productions), creating a sort of invisible spider’s web, into which all slip and from which they in fact cannot escape, remaining entangled. Furnishings and bits of scenery travel silently, in and out of the scene. Chairs and sofas seem to come and go by themselves; a horseless carriage brings the characters onto the stage, the trees in the garden run in on stylized panels, a bed appears and disappears. It is the bed upon which the exalted catholic Amalia dies, but not before she uses it to “possess” a young worker by biting him.

Ronconi claims to have followed the novel to the letter, using only the words of Gombrowicz, and not changing one. “I keep everything in the present,” Ronconi has noted, “leaving the occasional past tense, which creates a sense of disorientation.” He recalls that the author of Pornography wrote a story in first person, pretending to be a protagonist, while he is the omniscient narrator, winking to the reader and asking for his complicity. Placing this work in the theatre involves dealing with three different temporalities: that of the real author, that of the “fake” Gombrowicz, protagonist of the novel, and that of the story actually told. This is quite a challenge for the actors. It is not often that one finds in a text originally written to be represented, so complex a temporal layering. Ronconi therefore asked his actors to recite the lines in the first person with third-person descriptive portions, without departing from the words written by the Polish author. The commingling of storytelling and theatre has a long history, and Ronconi in particular has worked several times in this area, producing some of his most celebrated works. Among these were his Furioso, his Pasticciaccio and his Karamazov. In the present case, this process is facilitated by the highly theatrical nature of the novel, which often makes references to the fictional machine of staging. Gombrowicz has several times experimented with the writing of plays. Yet, it is precisely his novels which reveal a distinct and particular “theatricality.”

Concerning the staging, the director explains: “I’ve turned the novel into a play, but only by transferring the novel onto the stage. Gombrowicz’s writing remains what it is. Novels, when they change their destination and arrive at the theatre, reveal a different and equally interesting aspect as comedies.” The novel was chosen by the director to give depth and continuity in his quest for an infinite spectacle—that provides experiences in all directions, textual and spatio-temporal, that seeks to escape from the overly rigid boundaries of conventional dramaturgy; this is a common thread that runs all through Ronconi’s theatre. Without ever betraying the text, Ronconi always is devoted to creating its internal rhythm, its own specific language.

The complex drama created by Ronconi is realized out of a series of possibilities: the actors’ performances alternate interventions in the first person with others in the third person (concerning one’s own character or other characters); first person speeches sometimes turn out to be the thoughts of another character. In some cases, one has the feeling that it is the action on stage which comments on the words, sometimes the words seem to comment on the gestures. The “dramatic score” created by Ronconi is played out from the beginning on these registers. The theatrical and performative level quickly takes precedence over the narrative; the viewer is catapulted into a story translated into action, quickly forgetting that the actors are not talking exclusively in direct form, as is normally done on the stage, but predominantly using the indirect discourse. They tell a story telling their own stories, clearly following a technique of alienation.

Looking more closely and in detail at the operation of directing and dramaturgy proposed by Ronconi with Pornography, the question becomes more complex, interesting, and more clearly articulated. Since the sixties, the theatrical masterpieces of Ronconi have been characterized by their opposition to traditional dramatic forms. In the stagings of this director, the tension between “mimetic (or dramatic) mode” and the “diegetic (or narrative) mode” has assumed forms that are extremely interesting and exemplary. Piermario Vescovo’s reflections on this theme are illuminating (Vescovo, Il tempo a Napoli, 2011, especially pp. 123-146). As has been noted, there have been many dramatic experiments of this sort during Ronconi’s extraordinary career: the staging of the film adaptation of Nabokov’s Lolita, in What Maisie Knew by James, on to experiments that went beyond the scenic transposition of the novel, as in Barrow’s Infinities, The Last days of Mankind by Kraus and in the famous theatre and television versions of the Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto.

In this context, great interest in the theoretical aspect, as well as in the narrowly spectacular, has given rise to an “all-encompassing assumption of the text.” This is the path chosen by Luca Ronconi in some recent shows, in which the director brings to the stage the same diegetic dimension, making the actors “recite the story.” Ronconi is the one that more and more faithfully insisted on this wager: first and with a spectacularly happy outcome in the Pasticciaccio of Carlo Emilio Gadda (in 1996), then with The Brothers Karamazov, a creation which was realized only to two-thirds (in 1997-98). Concerning this, interrogated on several occasions, Ronconi defined his “scenic accomplishments” as “a simple transfer of literary material from the page to the stage, not a dramatization.” It is not, therefore, the usual procedure which has as its aim the “reduction” of a novel to drama.

In Demons by Peter Stein (2010), to take a recent and theatrically successful example, the German director understands the great Russian novel and its great durability as a “dramatization of characters,” with only marginal monologues that are properly speaking narrative-descriptive, created from the thin and limited interventions of a “character-narrator.” In the case of Pornography, we are instead facing a theatrical assumption of the novel in its entirety (as much in the parts in dialogue as in those narrated). Ronconi justifies this choice of research and experimentation, starting from his declared dissatisfaction with the traditional forms of theatre: “It seems difficult to fit contemporary issues into formal structures linked to a dramaturgy of the Enlightenment or the nineteenth century. My dissatisfaction stems from this.”

Just as in 1996 for the staging of Pasticciaccio and unlike what commonly happens, in Pornography Ronconi did not choose to translate the story using the first person. In the pages of the novel, the narrator begins his story by describing the characters, while in the production the actors step into the shoes of the characters, assuming the description without using the “I” but playing directly in the third person. This “depersonalization” is certainly the master stroke or the constitutive element that initially and most significantly affects the viewer; he must accept that the characters speak for themselves not only in the first, but also and especially in the third person.

The desire to reformulate the conventional rules of drama puts central attention on a reflection of particular interest on these same processes in the definition of the character. We are not here dealing with the adaptation of a novel into dramatic form, nor of the staging of the novel in its literalism (as we tend to believe), but to something in between and far more complex. It is a matter, in essence, of a possibility intermediate and fluid between that of the theatre of adaptation and that of the theatre of alienation. In watching Pornography, the spectator experiences a sort of bi-localization, a doubling of the actor. The characters continue to talk about themselves in the third person, they remain, so to speak, on the outside, and yet they tell a story with which they have a direct and internal rapport. This is the truly central dramaturgical and directorial process of Ronconi: something that, while in apparent fidelity to the text, is instead deeply modified in its theatrical engagement. The shift, to put it posssibly in the terms of a narratological vocabulary, is from the external narrator who tells the story, to the internal words of the story from the point of view of the characters.

The dry contrast between narrative and drama find, in this middle ground, not only life and existence, but the process sheds light on a general theoretical question. If we consider some of the narratological categories used by Gérard Genette in his Figure III (1972), Ronconi’s productions could be broken down minutely into choices of “focus,” in the sense that this is the principle according to which the narrative that appears on the single page of the novel is divided into phrases assigned to various characters. Ronconi is attentive to the needs of “perspective” in the narratological sense of the term: that is, in assigning directly to the “one who sees” words, phrases or passages attributed to the characters they are seeing at that moment on the stage, instead of from the point of view of what the narrator sees – or from speeches which are reported by the narrative voice.

Reflecting carefully on the production, it is essential to ask: What happens, then, when a processs of staging—in the literal sense of the word—is applied to the words of a novel? One answer might be: the theatrical adaptation of the novel leads to the loss of the figure of the omniscient narrator in favor of the spoken word from the point of view of the characters. This is a basic principle, a threshold that marks the passage from the narrative to mimetic, from the pages of a novel to the platform of the stage. One could say: here the literary universe of the novel ends, and we find ourselves in the space of the theater. But the operation put into play or “staged” by Ronconi, in order to be properly understood, demands answers to further questions. For example, to which characters does the director give what the unified voice of the novel is narrating? On closer inspection, the distribution of the words among the characters comes from the choice of who is seeing, moment by moment, what happens (or whoever is involved in the first person).

What then remains of the “omniscient narrator ” of the novel that looks at the story from the outside (assuming the story is shared on stage between the “people” moving in the space of the story)? In other words, on that level of the complex and shared unity of the written page of Gombrowicz, what has been articulated and what has been dispersed, polyphonic in the staging? While we could attribute this to the creative vision of the director, on the other hand it seems possible to locate it also in the eye and mind of the viewer. The transition from the external narrator telling the story to the words spoken from the point of view of the characters in the story, destroys, in fact, what is commonly usually called “the omniscience of the narrator.” It is found again, if we may speak in general terms, in a unitary principle in the eye and mind of the beholder: everything we see, even if said by many on the scene, was “designed ” by a director and “seen” by a spectator (cf. Vescovo, 2011).

The “division” or articulation of the novelistic text made by Ronconi is not, of course, the practical working out of an abstract theory, but on the contrary, what seems like an abstract theory comes to light or is illuminated through a concrete case.

teaches theatre at the University of Calabria—UNICAL. His publications mainly concern the Renaissance and contemporary theatre. He was for years the cultural collaborator of the “Teatro di Roma,” where he also worked as assistant director with Italian and foreign directors (including Eimuntas Nekrošius).

European Stages, vol. 4, no. 1 (Spring 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Report from Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- Performing Protest/Protesting Performance: Golgota Picnic in Warsaw by Chris Rzonca

- A Mad World My Masters at the Barbican by Marvin Carlson

- Grief, Family, Politics, but no Passion: Ivo van Hove’s Antigone by Erik Abbott

- Not Not I: Undoing Representation with Dead Centre’s Lippy by Daniel Sack

- In the Name of Our Peasants: History and Identity in Ukrainian and Polish Contemporary Theatre by Oksana Dudko

- Performances at a Symposium: “Theatre as a Laboratory for Community Interaction” at Odin Teatret, Holstebro, Denmark, May, 2014 by Seth Baumrin

- Songs of Lear by the Polish Song of the Goat Theatre by Lauren Dubowski

- Silence, Shakespeare and the Art of Taking Sides, Report from Barcelona by Maria M. Delgado

- Little Theatres and Small Casts: Madrid Stage in October 2014 by Phyllis Zatlin

- Gobrowicz’s and Ronconi’s Pornography without Scandal by Daniele Vianello

- Majster a Margaréta in Teatro Tatro, Slovakia by Miroslav Ballay

- Remnants of the Welfare State: A Community of Humans and Other Animals on the Main Stage of the Finnish National Theatre by Outi Lahtinen

- Mnouchkine’s Macbeth at the Cartoucherie by Marvin Carlson

- Awantura Warszawska and History in the Making: Michał Zadara’s Docudrama, Warsaw Uprising Museum, August, 2011 by Krystyna Illakowicz and Chris Rzonca

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016