This past June, as the Flemish theatre season waned, I had a chance to see a few fascinating selections from this lively theatre community. In the wake of a momentous election which saw the rise of the Extreme Right, to the disturbing degree that Bart De Wever’s Flemish Nationalist party rose to first place, Flemish directors and companies continue to stand out in Europe for audacity, creativity, and direct connection with their audience.

While viewing one of the four shows at the performing arts complex in Antwerp, De Singel, I ran into Gie Cassiers, director of yet another show I had seen (Hamlet Against Hamlet) and Artistic Director of Antwerp’s principal municipal theatre, Het Toneelhuis. He reports that the Extreme Right’s assumption of power had not yet produced any form of outright censorship or pressure to change the form or content of the work produced, but intimated that their advent had already led to cuts for the performing arts. This is a logical development from one point of view, as eliminating the generous safety net and strong governmental support for culture that Belgium has long enjoyed is one key tenet of the Extreme Right. Still, it must be asserted from the outset of this article how foolish and contradictory it would be for a political party that claims ascendancy and—if it is not abusive to apply the word here—exceptionalism for Flanders within the overall Belgian landscape, to contemplate cutting the legs out from one of the language community’s most successful features. For Flemish theatre currently is by most measures more remarkable than the French-language theatre of Belgium, which is generally in a condition of stasis, while the Flemish scene continues its long run of innovation and excellence year after year.

Its theatre scene, furthermore, is recognized as one of the foremost in all of Europe. Flanders’ directors are sought after in Germany, Spain, England, and America. Gie Cassiers, Ivo van Hove, and Needcompany are just a few of the directors and companies that are regularly invited to appear at BAM in Brooklyn, at the New York Theatre Workshop and Lincoln Center, all in the American theatre capital. Jan Fabre regularly shows all over Europe in lavish productions and installations (and regularly, closer to home, at Montclair, New Jersey). And it is a matter of great irony and pride that Flemish Belgian—not Belgian French-language—productions have been specially featured for many successive years, generally being awarded prime venues such as the Palais des Papes, at the most solicited French-language showcase of all—the annual Festival at Avignon.

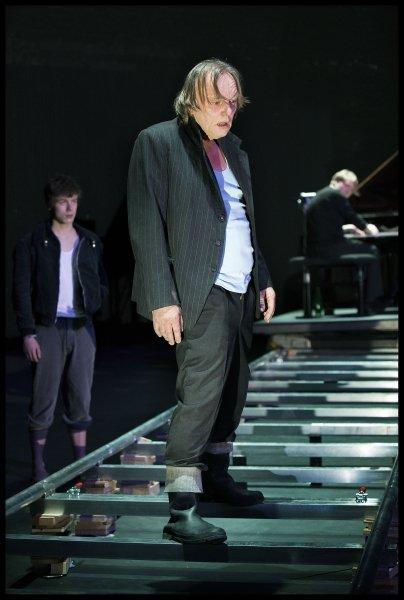

Gie Cassiers’s Hamlet against Hamlet, by Tom Lanoye, with ensembles from Toneelhuis and Toneelgroep Amsterdam. Photo: Jan Versweyveld

Theatre is one of the most visible and rewarding ways for any national community to gain recognition internationally. It is therefore a measure of the incomprehension and obliviousness to this precise point that would cause De Wever and his party to fail to see its value. Reducing the lush production values of Flanders’ theatres through budget cuts will only serve to lower Flanders in the eyes of the world and rob her of one of her most obvious ambassadorial media. I already see evidence of diminishment in Gie Cassiers’s latest production, Hamlet Tegen Hamlet (Hamlet Against Hamlet) by Tom Lanoye, which I caught in its final performance on tour at Brussels’ Kaaitheater, a troubling development for a director who has made his mark in New York and from whom we continue to expect so much.

Tom Lanoye’s reimagining of Hamlet has Claudius killing Hamlet’s father for political and idealistic reasons, not principally out of simple ambition or sexual jealousy, as an outside force threatens the Danish kingdom, requiring a strong response of which Hamlet’s father is supposedly incapable. The play is resolved by the return to the court of an impetuous Laertes who, in succession does away with Gertrude, Ophelia, and Claudius, since he finds that Hamlet has been too slow in resolving to carry out his revenge. Also, Lanoye mines the play for possible incestuous relations between Polonius and Ophelia. Further, whole characters such as Horatio and Fortinbras have been dispensed with. Lanoye employs Shakespeare’s text where it pleases him, cuts sections that vex him, and has written goodly amounts of original text to fill in as well, notably during a lengthy debate between Hamlet and Laertes toward the end. There is not necessarily a huge disparity between his language and Shakespeare’s when it is translated and typically streamlined into Dutch.

The production has a female Hamlet, here played by Abke Haring. This innovation will not strike an American audience as earth-shattering, considering that we had Diane Venora playing the role in Joe Papp’s production at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1982, that everyone took in easy stride (and hadn’t Sarah Bernhardt done the same many decades earlier?). Nor will the textual changes be so very disturbing, considering the plethora of liberties now being taken with Shakespeare everywhere. And mixing of Shakespeare’s texts with others’—notably by Lanoye himself in his 1997 ground-breaking Ten Oorlog (To War)—has also been done. When Shakespeare is performed in a different language than the original English, the blasphemy of combining his sacrosanct words with other people’s is greatly diluted. In general, Dutch-language translations of Shakespeare tend to strip it of baroque trappings and make it much more hard-edged and direct in any case.

We have come to look to Gie Cassiers for technical invention. He is a wizard with combining live-feed and recorded video imagery with live stage action. He uses video in ways that enliven the drama and make us forget the spoken text, so mind-boggling is the ingenuity of the visual dimension of many of his productions. Here, there is a metal armature down-center, like a sort of angular mechanized tree, with odd-shaped screens plastered all over it. On these screens, throughout the production, appear morphing colors, transforming images of the actors’ faces, etc. The rest of the stage is essentially naked, and the scenery and video dimension of the show are far less commanding and compelling than in his other shows; this relegates them to mere background for the action, and the remaining action is essentially verbal.

If the result then appears fairly conventional, we consequently look to the actors for resplendent acting and the author for brilliant revisioning of Shakespeare. Neither really occurs. All we have are stolidly competent actors and a version of Hamlet that is mildly interesting without the bells and whistles we expect from Cassiers’ fertile mind. We are absolutely willing to cut both Lanoye and Cassiers some slack. They are world leaders in theatre production, and here they seem to be treading water. One does have to wonder if the slender pickings on the level of theatrical spectacle are the result of a diminished budget (see above), or a weariness of the imagination. Time will tell.

Luk Perceval is back in Flanders! He, arguably the best director of a generation of brilliant talents who had been one of the co-directors of Blauwe Mandaag Compagnie and founder of Het Toneelhuis, site of the transformation of Antwerp’s municipal theatre that had set off the chain reaction which overturned the entire calcified Flemish repertory system, had then been lured away to Germany. The higher salaries and handsomer production budgets there prompted his departure some years back, but he now returns annually to do one or more shows with NTG, the large municipal theatre of Ghent. This year’s tour is actually a revival of last year’s feature, Chekhov’s Platonov. Chekhov is one of Perceval’s strong suits, and over the years he has staged most of the major plays. One of his earliest productions, through which he first made a name for himself, was The Seagull. For those who saw Perceval’s Seagull, the aesthetic approach to Platonov will seem quite familiar, but this venture into self-imitation proves equally rewarding to the earlier work.

Perceval’s treatment of Chekhov texts at once taps into the essential kernel of the human drama in all its humor and pathos, and is blasphemous toward the traditional costume drama approach to mounting it. The first slap in the face of tradition is textual. Perceval has eliminated half the characters and many sub-plots and plot twists, in a sense making the whole action retrospective. The second affront is scenic. Swept away are the late Victorian interiors, replete with knickknacks and samovars, to be replaced with a simple line of chairs parallel to the footlights in the richly encrusted Victorian seating section of the Bourla Theatre. In this case, there is also a grand piano placed prominently downstage at the near end of a track—like a railroad track running diagonally from downstage to upstage. And that’s all the scenery there is.

While on a few occasions the actors walk along the raised tracks in pursuit of each other, the height of the tracks obliging them to lift their legs ‘way up over them only afterwards to sink down into the interstitial spaces and, in effect, to sprint in slow motion, the principal purpose of the tracks is for the piano, which at some point in the show, moved imperceptibly all the way from downstage right to upstage left. It was shocking to realize that I’d never seen something so large actually move, only to reappear elsewhere. Perceval is a master of directing the audience’s attention where he wants it to go.

It should also be noted who is at the piano—Jens Thomas, whose instrumentation and vocal improvisations support the dialogue throughout. He uses both the keys and innards of the piano to produce a wide variety of soundscape. The auditory dimension encompasses both highly melodic, rich tones and gut-originating and wrenching non-verbal vocalization to accompany, reveal subtextual undercurrents, and underline the emotional lives of the characters. He is always in sync with the actors’ intentions.

The gallery of characters—simply arrayed in a line on the downstage and only sparingly slipping into new spatial configurations, but rarely ever using the stage’s depths—are notable for bright, bold, and mostly grotesque individuation. Perceval leads his performers to unearth some, often peripheral, aspect of the person’s psychology and allow it to expand and pulsate throughout the play with untrammeled extremity. For example, Steven van Watermeulen plays the role of Sergei as though he were an Asperger’s case. The old servant Osip, played by Hugo van den Bergh, is a drunken sot. Indeed, excessive drinking saturates several actors’ performances. What is subtly suggested in most productions, such as the illicit sexual attraction subliminally pulsating between various characters, here is pushed out onto the plane of realization, with embarrassed and self-incriminating candor. It’s painful and hilarious, realistic and clownesque, all at the same time.

Another hallmark of Perceval’s work is his free and easy approach to text, compressing scenes, eliminating huge swathes of exposition, and allowing actors to repeat words and phrases à la Tourette’s Syndrome. The characters are, in many cases, psychologically ill, not just troubled—twisted, incompetent washed-up husks of human life crashing into each others’ lives and wreaking havoc—and all scenically naked with only their deeply imbued acting to carry the performance through and hold the audience in an extended state of rapt fascination.

As is typical in Perceval’s productions, the actors have been encouraged to use their own local dialects, one of which was impenetrable not only to an English speaker like me, but also to fellow-Flemings in the audience. The denotative incomprehensibility actually enhances the comedy, and the audience appeared to find everything that actor said hilarious, as did I, although it was frustrating not to be able to understand the basic ideas being expressed. It is almost as though Perceval were saying: We’ve seen this classic play before; we can always read it if we wish. I’m going to make a production that plays fast and loose with the text which places the audience’s enjoyment ahead of fidelity to the author’s original words.

A theatre company that has been going strong for many years now, but whose work and fame have managed to elude me, is Abattoir Fermé, slogging along for fifteen years in the unlikely medieval city of Mechelen (Malines). Working in small venues, they sell out their annual runs months in advance to their cult following. While Mechelen tends to be a conservative city, the work done by Abattoir Fermé is provocative and sensational, pushing against and overrunning all boundaries of taste and ethics. A small collective of devoted artists, it works in the gray area between performance art and theatre, and recalls radical experiments of former times such as Happenings in the late 1950s and—especially—the audacious performances of Squat Theatre in New York in the late 70s.

A fly is heard buzzing in a circle. A fog machine has released a miasma over the space. A human figure is seated stooped over a table covered in a plastic drop cloth from inside of which capsule a light expands and contracts with the actor’s breath. It eventually becomes apparent that the light inside the plastic tent is emanating from a lit cigarette. After what seems like an eternity (the show runs a mere hour, but feels much longer) a recorded voice speaks, referring to a bizarre crime in which women are mysteriously disappearing. For some reason, this voice and all spoken passages are delivered in English. At length, the actor removes and folds the drop cloth. He is revealed to be a particularly unappealing naked, bald, corpulent middle-aged man. He systematically gets dressed as he continues to smoke.

The rest of the space is dimly lit; now and then a given area that had been unobtrusive comes into focus. A hand creeps out of a trunk that is now revealed upstage right. It flips open the lid and a woman emerges like an image from a horror movie backed up by creaking sounds also out of horror movies. She stands center stage as she converses with a recorded voice (divorced from the middle-aged man in our view, but manifestly related to him and his agenda), revealing that she is being welcomed to an audition for a film role; she will be asked to do certain things as part of the audition and she naively agrees. It is clear that she doesn’t know what she is getting into.

The actress lies down on a table and a second actress appears, and covers her under strips of wet clay until her entire body disappears. She then distributes miniature human and architectural figures as well as tiny trees over the mound, creating from her supine, submerged form a detailed landscape. This segment is the most enjoyable part of the show.

The second actress undresses herself; the man gets physical with her but then makes himself scarce, sitting off to the side and smoking. She, now entirely naked, starts writhing and flinging herself backwards, uttering sounds as though she were being subject to unwelcome, forced sex, while a laugh track plays over the sound system. This painful segment goes on for some time until she lapses into sobbing. The man, meanwhile, blows a noisemaker over the miniature landscape (underpinned, if you will recall, from the other actress’ dissimulated body) and sets off sparklers. He sits her up and blows dust in every direction, causing the action to be masked from the audience for a time.

One of the actresses then places the plastic drop over the man’s head, and he breathes with the plastic stretched over his face. He is made to lie down and she stands over his supine body, then drives a miniature automobile over this newly created human landscape. The first woman removes the layers of clay covering her and stands powerfully singing Purcell’s baroque ballad, “’Tis Nature’s Voice,” a cappella.

This non-linear piece has resonances of rape, seamy episodes of sexual exploitation, and sado-masochism. It recalls the theatre of Jean Genet, of Artaud, of Grand Guignol, of Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysterical Theatre in its claustrophobia and oppressive sound-surround of recorded voices, and of Hell House. It shoves disagreeableness deliberately at the audience without casting moral judgment on the acts perpetrated. Is it exploitive to make the actresses play such bathetic, if fragmented, scenes? Is it sensationalist to stage scenes of such frank, abhorrent lewdness? The audience takes it all in stride and seems to appreciate it fully.

It seems that this is one of Abattoir Fermé’s earlier pieces that they brought back and that their more recent work tilts more in the direction of theatre than performance art—a series of related but discontinuous images. But what unites all their work is a certain daring and provocative tendency. For example, in the coffee table book which lays out their history, they claim to draw their aesthetic from the theories of one Wilfried Peteet-Borremans, a mysterious theatre worker who developed his ideas during a long sojourn in Hollywood, and include many of his manifestos in their literature. Peteet-Borremans, it turns out, is a total fiction, a chimera.

This performance is not easy to like, since it works with such dreadful characters, issues, and atmospheres, resisting also resorting to a literal or direct way of relating a story. But one has to hand it to Abattoir Fermé that they take such an uncompromising approach in a period such as this where pressure is on from the Extreme Right to tow the line of bourgeois middle-brow taste. They are not backing down one iota from their chosen difficult and off-putting aesthetic path; it is also gratifying that they have gained such a loyal, unflinching audience that converges on Mechelen for the long-awaited treat.

The well-known actor-director, Josse DePauw, has staged a diptych of two one-act plays by Michel de Ghelderode, The Strange Rider, and the Women at the Tomb, under the blanket title Huis (House) presented by Lod Muziektheater at the large performing arts complex De Singel in Antwerp. Ghelderode, a Fleming who wrote experimental, idiosyncratic theatre in the French language from the 1920s through the 50s, best known for such plays as Pantagleize, Escurial, and Barabbas, and had a vogue in America in the 1960s during the Absurdist craze), is now infrequently revived. But juxtaposed against each other and presented in Flemish translation, these two plays are dripping with theatrical life and energy. The large casts—The Strange Rider composed uniquely of men and The Women at the Tomb exclusively of women—are backed up by the Symphonisch Orkest and Opera Vlaanderen providing background music and singing throughout.

The Strange Rider is a post World War I oeuvre de jeunesse by Ghelderode, written in the wake of symbolism in the style of the Belgian Nobel Prize winner, Maurice Maeterlinck. Indeed, it is a blatant imitation of his 1890 masterpiece, The Blind, and partially for that reason, almost never put on. It takes place in an old age home where the inhabitants hear the ephemeral sound of horse’s hooves approaching. An intentionally ensemble piece, the sound heralds the metaphorical imminence of death for the aged men. The rhythm and music of the spoken voices resound like tocsins.

The Women at the Tomb is a New Testament play which imagines all the important women in Jesus’ life taking refuge immediately after his crucifixion in a cave consecrated to the burial and enshrouding of human cadavers. As each successive woman enters, gives her version of what she has just witnessed, and reveals her emotional and ethical stance to the events, she is welcomed by two simple and caustic old ladies, the cadaver washers. While in the first play, the men form a kind of anonymous chorus in which their individuality is absorbed, in this one there is much more emphasis on the individual personalities of each of the women, already known to us from the Bible, but explored here in a fresh and disarming way. They are, in effect, interviewed by the two corpse-washers whose attitudes to both the other women and the presumed holiness of the crucified Christ are skeptical and subversive, offering an audaciously bathetic counterpoint to the otherwise awe-inspiring event.

In both plays, DePauw’s settings are minimal to the point of non-existence, consisting of a few entirely unevocative platforms on the vast, empty stage. The lighting too is devoid of ambiance, and the costumes for the men, in any case, are simple ragged schmatas. The staging is rudimentary, though sufficient; but the small stab at choreography is embarrassingly inadequate.

All the resources of this production have gone into how it sounds. The music, sung by a large chorus, is haunting. But the principal interest of the show is in the speaking of the text, which is overpoweringly beautiful, even though—or partially because—the majority of the actors are amateurs. The original French text is delivered in super-titles above the stage. And the actors generally speak in the guttural and visceral Flemish accents of their place of origin—so a linguistic pot-pourri. Whereas the original French of Ghelderode’s texts is uniform and essentially classical and high-brow in tone, the Flemish accents we hear are the language of the real common people—and most of the characters in both plays are common folk. The translation from French to Flemish by Monique Nagielkopf is utterly colloquial, which encourages the actors to deliver their texts without pretension, giving their acting a naïve directness, sincerity, and earthy humor that binds the two spiritual fables and obviates the absence of other production values. Here is theatre at its most basic and moving—a theatre by the people for the people. It is still avant-garde, but it invades the public with irresistible shared humanity over the most universal of shared experience: that of death.

In my opinion, this production is the consummation of how Ghelderode would have preferred his theatre to be done. He chose to write in French because it was the cultural language in the Belgium of his day; but he was infinitely moved when his works were put on in Flemish in the 1920s and 30s by the Vlaamse Volkstoneel, the main itinerant Flemish company that played all over the country for a humble public. And it is clearly in those Flemish dialects that his unorthodox spirit is mostly faithfully transmitted, for they contain within them an inherent music concatenated of irony, aspiration, and coarseness which are a joy to hear; Ghelderode’s thought here is matched with its native spirit.

The four shows I saw bespeak a richness of creativity and aspiration in the Flemish community. While all four were quite different from each other, they shared an exploration of language that rejects an administratively approved cultural parlance to opt for research into the savory everyday languages of the people, and their personalities as manifested in the way they speak. And they further all shared a boldness in theatrical expression without concession, albeit in four distinct directions. And finally, they take on big subjects and find a strong echo with the public that flocks to see and hear its artists, claiming strong affinity with them and support for their most risky creative forays.

is the author of seven books on Belgian drama; his The Maeterlinck Reader, co-edited with Daniel Gerould, came out in 2012. Other titles include: Three Plays of Forbidden Love by Hugo Claus, Ghelderode, Three Fin-de-Siècle Farces, Theatrical Gestures of Belgian Modernism, Four Works for the Theatre by Hugo Claus, and An Anthology of Contemporary Belgian Plays. His many articles have been published in Contemporary Theatre Review, Plays International, The Drama Review, Modern Drama, Western European Stages, Symposium, etc. He is Professor of Theatre at City College and the Graduate Center, CUNY and has been awarded the Prix de Rayonnement by the Belgian government. He is currently translating works for an anthology of recent francophone Belgian plays and writing a book on the Flemish director Ivo Van Hove with Christel Stalpaert.

European Stages, vol. 3, no. 1 (Fall 2014)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

• The 68th Avignon Festival 2014, July 4 to 27: Protests and Performances by Philippa Wehle

• The Avignon Fringe Festival 2014 by Manuel García Martinez

• The Reality Bites of New Bulgarian Theatre by Dessy Gavroliva

• Happy Days: Enniskillen International Beckett Festival 2014, July 31-August 11 by Beate Hein Bennett

• Flemish Theatrical Exceptionalism Mostly Glimmers, Sometimes Wavers by David Willinger

• Shouting at the Devil (and Everyone Else): Yaël Farber’s Production of The Crucible at The Old Vic by Erik Abbott

• Mladinsko Theatre and Oliver Frljić’s Damned Be the Traitor of His Homeland! (Sibiu International Theatre Festival, Romania, 2014) by Ilinca Todoruţ

• Barcelona Theatre (2013): Responding to Spain’s Crisis by Maria Delgado

• Report from Madrid by Duncan Wheeler

• Irish Colonial History on the Hungarian Stage by Mária Kurdi

• Fantastic Realities: Actors as Puppets and Puppets as Actors by Roy Kift

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2014 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016