Brno, the second largest city in the Czech Republic, has been quite overshadowed culturally by Prague, but it nevertheless has a rich cultural life of its own and a thriving varied theatre scene, which I had the pleasure of exploring on a visit there in mid-May of 2014. The city’s leading theatres are the three national theatres. The oldest of these, at least in terms of physical structure is the Reduta, housed in the oldest theatre building in central Europe, where the young Mozart and his sister performed in December of 1767. At that time the building, actually dating back to medieval times, and converted into a tavern in 1605, had been operating as the Taverna Theatre for more than a century. Since the eighteenth century the premises have undergone fires, closings, remodelings, and conversion to other uses, so that the present interior, almost totally rebuilt in 2005, shows few traces of its long history, though the elegant front hall, where Mozart performed, looking out onto the oldest market square in Brno, retains its original shape and windows, but little other decoration. The actural Reduta theatre is an elegant little modern space built in a modified eighteen-century style, in another area of this same upper floor.

In the Reduta I saw a type of production not uncommon in the more experimental stages of the city, but seen in this theatre for the first time—an intimate audience actually seated on the stage and surrounding the actors on three sides. The play was a contemporary adaptation of the Truffault Jules and Jim, which followed the general action of the film fairly closely, but had a much more improvisatory feel, not surprisingly because the three characters, Jiří Kniha (Jules), Michal Dalecký (Jim) and Petra Bučková (Katty), are all well-known improvisatory comedians as well as traditional actors, the first two often working as a team.

This production, premiered in 2012 and directed by Anna Petrželková (the former director of this theatre, who moved this year to direct the famous Theatre on the Balustrade in Prague) with dramaturg Dora Viceníková, clearly builds upon the comedic and improvisatory skills of these three performers. The setting, by Zuzana Štefunková, is basically a simple, but extremely flexible one, the main acting area containing three black tables, each with two chairs, and a simple table lamp suggesting the shape of the Eiffel Tower. At the beginning the impression is of a small café, but the tables are on wheels and can moved into all sorts of combinations and often used as carts or trollies for the gymnastic routines of the men performers. At the rear of the playing area is a raised platform made up as a bed, with a large, heavily patterned curtain behind it, suggesting the wall of a room but also used, as the production goes forward, for a variety of projections, including the classic bust that infatuates the two young men and filmed battle scenes for the war sequences.

The Truffault film was noted among other things for its imaginative use of original filmic effects, and although a few of these are suggested in this adaptation, this element is replaced by stage effects, including clown routines, gymnastic displays, and songs by the two men (accompanying themselves on guitar and ukulele). The effect of a kind of vaudeville presentation is enhanced not only be the snatches of song the actors present but by frequent bursts of offstage music accompanying many of the physical routines. The musical score, by Mario Buzzi, relies heavily on repeated quotations of French and American popular music of the 1950s, especially, the ironically often-repeated “It’s a Lovely Day Today” and the rollicking “Portuguese Waserwomen.” Perhaps most strikingly, the two men interact often with the women seated in the first row, right next to the action, flirting with them and offering them flowers or little notes with telephone contact numbers (in fact the offices of the theatre). The two-man clown show impression is reinforced by the ingenious costumes of the pair, the work of costumer Zuzana Štefunková. The right side and left side of each costume are contrasting, but in mirror image, so that the right side of Jules’ suit matches the left side of Jim’s. One of these costumes is a plain grey suit, but with a flowery lapel, while the other side is a flowery suit matching this lapel, with a gray lapel matching the first side. This effective device is reinforced by the fact that the “wall” behind the bed is decorated with the same floral pattern, unifying and theatricalizing the whole visual field.

The convention of audience interaction with women of all ages is so well established that when, about twenty minutes into the production, the men encourage (indeed half force) a woman audience member to join them on stage even theatre-wise audience members, such as this reviewer, were momentarily convinced that she was actually a member of the audience, so well did she portray her confusion and reluctance. We soon realized, however, that this was the third member of the triangle, and in fact a highly talented and popular young Czech actress. Encouraged to don a costume which was a complete floral outfit, she soon joined in the routines of the two men and showed an equal skill in physical, vocal, and musical sequences, producing a symbolically weighty musical saw to accompany their two stringed instruments.

The light-hearted burlesque mood of the early part of the production gives way after the war to a darker tone, but the production has already so committed itself to a kind of vaudevillian approach (never fully abandoned) that despite more conventional and darker costumes and the suggestion of aging, that darker emotional tone was never fully achieved, and the closer that one came to the ending, the further the tone departed from Truffault’s tragic conclusion. As a result, this version, though still theatrically effective, seemed to become more calculated in its effects and less convincing in its emotion as the evening went on. The admittedly striking ending shows this clearly. In Truffault’s film the action ends with the car crash suicide of Jim and Katty and with Jules left to bury the ashes of his friends. In this production this situation is suggested by an effective but abstract theatrical image. Jules, who has served as a kind of internal director, complete with whistle, for much of the last part of the play, mounts an abstract wooden rocking horse center stage, facing the bed. The “wall” behind the bed rises, like a stage curtain, for the first time, revealing Jules and Katty on identical horses, but in a separate visual world. Thus the realistic tragedy of Truffault is converted into a theatricalized scene of reconciliation, at least visually if not entirely emotionally.

The National Theatre in Brno in fact includes three theatres. The Reduta was the first such theatre, but when it was closed after a major fire in 1870 a major new house, modeled on the National Theatre in Prague, was built in 1882. It was the first theatre on the continent to install electric lighting, designed by Edison himself. This is now the Mahen theatre, and the main dramatic theatre in Brno. Here I saw a very striking post-modern Othello, directed by the Slovak director Rastislav Ballek, based in Bratislava, who directs frequently in Brno, most recently a highly innovative Doll’s House at the Reduta. Othello is his most recent creation, having opened less than a month before I saw it in May of 2014.

One of the many unexpected features of this production was the use of language. For the role of Othello, Ballek cast one of his favorite actors, Robert Roth, generally considered the major actor of the contemporary Slovak stage. As has been the case with some previous Ballek-Roth productions, the actual interpretation of lines varies a good deal night to night. Ballek creates a general pattern of movement, but encourages his actors to experiment with their delivery and movement night to night, to encourage a sense of immediacy and even danger. This includes even the lines spoken, especially by Roth, who in the course of the evening delivers lines in Czech, Slovak, and occasionally in English, according to his choice at that moment. This increases the unstable and mercurial sense of his character. Thin and angular, he plays Othello not with the traditional rather simple nobility, but as a tormented soul from the beginning, rather as some actors play Hamlet in his mad scenes. This leaves the impression that although he is manipulated by Iago, his fate is really more self-created than imposed upon him. The production surrounds him with suggestions of black Africa, although Roth himself is white. His costume (designed by Katarina Holkove) includes tight black pants, jewelry, earrings, and black painted nails, evoking “black” rock stars like Michael Jackson. Occasional African ritual objects or shields are illuminated briefly upstage all during the evening. At the beginning of the comparatively short second act, which is primarily devoted to Desdemona’s final moments, the upper part of the proscenium is filled by a curtain upon which a video loop shows an anguished Othello smearing black paint upon his face, although the live actor below is still white. Desdemonda’s murder is staged as a kind of grotesque primitive ritual, with Othello, almost naked and his body now completely black, strangling her in one of the most cruel death scenes I have seen in productions of this play. Desdemona (Lucie Schneiderova) struggles and moves convulsively for several agonizing minutes before finally succumbing, and she does not revive.

This Iago (Bedrich Vytisk) is not really a villain, but rather a contemporary political manipulator, whose suspicions of Othello’s interest in his wife Emilia (Eva Novatna) are clearly justified according to the close connections we see between the two on stage. Dressed in a modern grey executive suit with a pink tie, he has the most contemporary feel of any character in the play, and rather oddly, bears an uncanny resemblance to the recently departed American actor Philip Seymour Hoffmann, who played a somewhat similar Iago in one of his last major stage roles. The ineffectual Venetian state shown in this production is helpless in the face of the violent events of the concluding scenes. The Doge, elegantly clad in full renaissance costumes, and his black-clad companions, flee in terror as Iago shoots his hapless companion Rodrigo (Michal Delecky) and then his wife. Dropping the gun center stage, before the crushed Othello, Iago strolls nonchalantly off the stage up the side aisle, and out of the theatre, presumably to carry his own destructive agenda in our own world. Othello, left alone with the corpse of his wife, delivers an extended and almost hysterical death-speech/confessional, waving the gun menacingly toward the audience and finally placing it in his own mouth as the lights go out and we hear its shot.

The lighting and setting, designed by Josefa Cillera, open the vast National Theatre stage entirely, creating an enormous black void with characters normally appearing in pools of light. Most scenes are played in an intimate area down center, but there are always individuals or small groups of actors scattered in their own small pools of light upstage. Usually these simply pose, but occasionally they mime actions, apparently, according to the concept of the director, according to their own choice that evening. Othello, in keeping with his erratic presentation, often roams about the stage, coming in and out of these pools of light, while the other characters tend to remain more stationary. This adds of course to the erratic, unstable character he is portraying, which in the end, while effective, rather disturbingly suggests the “savage” quality of his African roots.

The following evening I attended a performance in a much more unconventional venue. This was in the Villa Tugendhaft, a masterpiece of functionalist architecture designed by Mies van der Rohe in the 1930s and now on the UNESCO World Heritage List. A small audience was seated on three sides of the villa’s open living room, the fourth wall of which was a glass wall looking out over the city of Brno (the building is perched at the top of a small hill). In this elegant space, the Czech dance company ProART presented for three evenings a double bill of Eric Satie’s “Christian ballet” Uspud and a contemporary composition, Emoticon, mixing bits of Satie with modern electronic music. Although the evening was described as “site-specific,” very little use was actually made of this location, though its minimal functionalist interior made it a very good neutral dance area. The first piece especially, performed by the gifted company leader Martin Dvorák and Ales Slanina, accompanied by Richard Pohl on the piano, depicting the encounter of a Christ-like martyr figure with a series of supportive and opposing figures, really needed only a white sheet and the bodies of the two actors intertwining with it, and could be performed in any neutral space. The second piece, with Dvorák and Irene Bauer, utilized the space more directly, relating to its metallic columns and marble back wall in a powerful exploration of physical relationships. Although the dates of Satie himself turned out to be the closest tie to the actual performance space, it was still an impressive performance and the space itself was a stunning one.

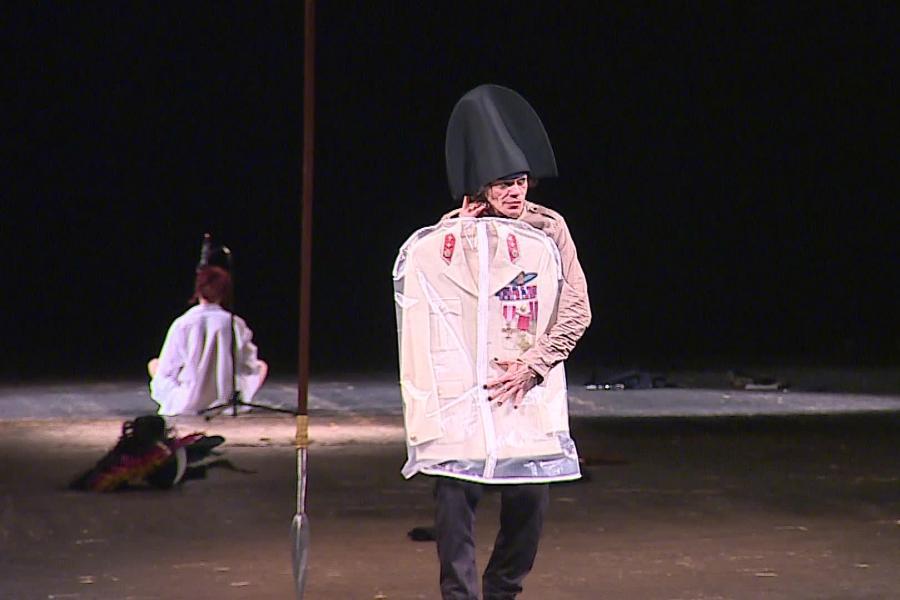

The following two evenings I was fortunate enough to view two classics of the Czech theatre in their land of origin, indeed in the city, if not the actual theatre of their premiere performances. These were the Čapek Insect Comedy and Janáček’s charming opera, The Cunning Little Vixen. The Čapek was presented at the Goose on a String theatre, one of the leading experimental ventures in Brno, located just across the old market square from the Reduta. The theatre’s director, Vladimir Morávek has a particular interest in presenting Czech classics in a highly visual and physical post-modern form. Currently his theatre is engaged in a series of four Capek revivals, collectively called “Čapek on a string.” One enters the theatre through a large open space on the ground floor, really a kind of museum of fascinating props—costumes, objects and animals, including a very large pig, and of course an impressive goose. I am told that the theatre often recycles objects from past productions as a kind of visual intertextuality. Going up a flight of stairs, one enters the main performance area, a very large and very well equipped black box, surrounded by narrow balconies. For this production the balconies are used only by the performers, with the audience seated in the center space, literally surrounded by the world of insects, who rush through them in all directions and also descend from the high ceilings on ladders, trapezes, and even a much-used sliding pole. The director has retitled the work “The Insect—Oh! What a Spectacle” and the change is highly appropriate. One is embedded in a continuing circus-type experience that at times is quite overwhelming. The leading role of the tramp is played by Czech TV and stage star Jan Zadražil. Although he plays the final scenes alone, during much of the production he is part of a chorus of nine identically dressed figures that from time to time sing his lines as a chorus. The costumes, not elaborate, but ingeniously suggestive of flies, butterflies, ants, beetles and slugs, were created by Silva Zimula Hanáková, and the strong musical score by Jiří Hájek. Individual performers were not identified in the program, but aside from Zadražil, particularly outstanding in the large cast were the young woman discovered sheathed in a plastic chrysalis at the opening, who struggles to emerge through the evening, and the grotesque parasite, with his flickering reptilian tongue, who roams with his stiletto among the case, dispatching them and pushing their bodies into a hellish smoking stage trap and then licking off he knife as he seeks the next victim.

The production I saw ran for a headlong ninety minutes, but I am told that originally it ran for twice that long. The major changes were the almost total elimination of one major sequence, the ants, and the simplifying of the ending which originally was played out in several different versions of varying optimism and pessimism. While I understand the pressure of time, I much regret missing the original version. The carefree butterflies clearly (and indeed a bit excessively) make their point about the ephemerality and thoughtlessness of life, and the dung beetles, carrying their huge and precious ball in a contemporary shopping cart, remain a wonderful image of acquisitiveness, but perhaps no aspect of the Čapek world is more relevant to modern audience than the nationalistic and militaristic ants, and their disappearance is a real loss. I can be less sure about the multiple endings, but I found the current single ending the only really weak part of the production, and that may have been ameliorated had we been given several choices. In the current version, the hungry slugs move in on the dying tramp in anticipating, holding knives and forks eagerly, but as they approach him, choric voices from offstage celebrate the joy of life and they retreat, leaving the tramp to be rather surprisingly redeemed at the end, to somewhat anticlimactically wish us all a happy day. I can only assume this was supposed to be ironic, but if so, the original achieves that effect as well as killing off the tramp. It ended what had been a striking theatrical evening on a distinctly puzzling note.

After seeing this highly unconventional interpretation of the Čapek work, I went the following evening to Brno’s third national theatre, the Opera, expecting, that the presentation of another national classic, Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen, would, like most central-European opera productions these days, depart sharply from expectations. I found on the contrary, and somewhat to my disappointment, that the presentation was a highly conventional, one might even say old-fashioned one. A glance at the program provided something of an explanation. Both designer (Neil Irlandais) and director (James Conway) were not in fact Czech, but invited artists from England, and the production, viewed as a conventional British interpretation was much more understandable. Conway is primarily known for touring opera productions in England and Ireland. Designer Irlandais created a flexible if not particularly handsome setting, essentially a rolling forest floor created of wire mesh with trap doors here and there in it so that the foxes could pop in and out and move about under its surface. Thin pine trunks, rather resembling telephone poles, thrust up out of it here and there and a large hazy moon shone through the forest branches upstage center. This construction was built on the theatre’s large turntable, which revolved to reveal a pie-shaped wedge that, with slight modifications, represents the various human spaces such as the forester’s yard and the inn.

The costumes, also by Irlandais, suggest a moderately well-financed children’s theatre production. The most interesting is a moose with stick-cane forelegs, faintly suggesting something out of The Lion King. The rather amateurish look of the production and the directing was happily at least somewhat compensated for by the music. Tereza Kyzlinková, one of the country’s leading operatic stars, created a charming and highly sympathetic vixen, the National Theatre orchestra, led by Jakub Klecker, was excellent, and the community of little foxes, performed by a children’s choir of the city and directed by Valérie Matsova, were quite delightful. Despite its rather old-fashioned approach, the production still offered an engaging, if not particularly challenging evening of theatre.

, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is The Theatres of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia with Khalid Amine (Palgrave, 2012).