2013 was a very special year for the Berlin Theatertreffen, the annual festival presenting the outstanding works from the previous year presented in the German-speaking world. In 2013 this festival, one of the outstanding annual theatre events in Europe, celebrated its fiftieth year. Its success has been such that virtually every performance is sold out long in advance and a theatre public from around the world is attracted to its offerings. In acknowledgement of this increasing internationalization of the Theatertreffen audiences, the administration began several years ago regularly offering English supertitles over the performances.

The 2013 festival began spectacularly with a production of Euripides’ Medea, created by a number of the most highly regarded artists of the contemporary German stage. Its director was Michael Thalheimer. Thalheimer has had six productions selected for the Theatertreffen, most recently the Oresteia in 2007 and Hauptmann’s The Rats in 2008 (both reviewed in WES). The powerful minimalist style of Thalheimer is one of the most distinctive on the present German stage and has exerted a significant influence on other directors.

As is the case with many leading German directors, Thalheimer works almost exclusively with a single designer, Olaf Altman, who is clearly co-equal with Thalheimer in creating the distinctive world of their productions. Altman’s setting for Medea ultimately recalls the minimalist but enormously powerful settings he created for previous Thalheimer productions, especially the Oresteia, but this similarity was by no means apparent as the production opened. We were greeted with what appeared to be a completely empty, grey stage, the cavernous performance area of the Festspielhaus stripped to the walls, with only an occasional lighting instrument visible. Nothing apparently could be further from a typical Altman design which totally fills the visual field with monumental walls and inclined planes. As the production begins, the central section of the apparently solid back wall rises, revealing a shallow inner stage, distinctly recalling that of the Orestia, but far removed from the audience. For the Oresteia, Altman completely filled the proscenium arch with a massive, bloodstained wall. A narrow platform about six feet from the stage floor extended across the face of this wall and an equally narrow platform extended along its base. These two platforms made up the entire acting area.

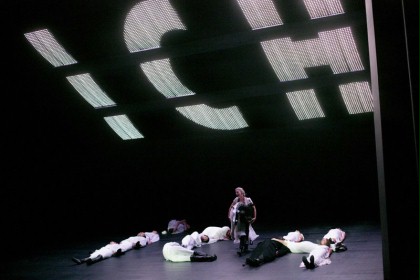

The area revealed at the rear of the vast Festspielhaus stage almost duplicates this arrangement, except that the wall is not spattered with blood but is a uniform dull grey. Its upper ledge is at first empty, but will soon be occupied by Medea (Constanze Becker), who will remain alone on this platform usually near its center, throughout the evening. All of the other actors perform on the stage floor below. The first of these is the Nurse (Josefin Platt), who begins the action with a stunning opening sequence. In almost total darkness we hear a deliberate and measured clomping of heavy footwear (kothorni, perhaps?). A shaft of light from down left offstage shoots across to fall upon the wall up center. A shadow appears upon it, which we discover is that of the heavy trodding nurse, who finally appears, lit only from the back, a black-clad, stooped, and grotesque figure, who finally reaches the bottom of the upstage wall and introduces us to Medea, who appears later in a spotlight on the walkway above. Rarely is the entire stage illuminated—actors appear often in pools of light or in powerful and striking beams from the side. The stunning lighting design is by John Delaere.

The next character to appear is the Chorus, played quietly but intensely by another of Germany’s best-known actresses, Bettina Hoppe, who normally positions herself upstage left near the base of the wall. Creon (Martin Rentzsch), Jason (Marc Oliver Schulze) and Aegeus (Michael Benthin) normally take up positions further downstage. Although their performances are intense, they are also physically isolated one from another. Each remains in his own pool of light in widely separated locations on the vast stage.

When Medea announces her course of revenge, however, the entire physical surroundings alter, and we see designer Altman at his most striking. The distant wall with Medea on it slowly begins to move forward, seeming to grow in size, until at last it totally fills the proscenium arch, and we recognize the same spatial configuration that Altman utilized in his famous Oresteia setting, essentially an overwhelming wall with two narrow walkways—one at the foot and the other some six or seven feet higher. This remains the configuration for the rest of the evening, with Medea on the upper level even when she is crouched in a suffering heap towering over her victims below. Inevitably one is reminded of Becker’s brilliant performance of that other icon of female revenge, Clytemnestra, six years ago in the memorable production by this same creative team.

No children appear in this minimalist interpretation and no exiting chariot. The death of the children is presented as an animated video, created by Alexander du Prel and projected directly onto Medea. In a large black and white box, simple figures of a family like the stick figures on traffic signs indulge in a sequence of everyday family activities, playing, walking, reading, traveling, even watching TV together. The images speed up and flow into one another until finally they are replaced by images of knives and violence, and at last two diminutive figures lying unmoving side by side. It was an imaginative way to provide an alternative to onstage children, but in my opinion much less effective than the rest of the evening, such as the brilliant articulation of the messenger speech by Viktor Tremmel who had to struggle continuously to produce the ghastly words that seemed stuck in this throat, or the heart-breaking speech of Marc Schulze as Jason when the full enormity of Medea’s deeds breaks upon him. For a long moment he struggles with a silent scream, evoking Helene Weigel and Edvard Munch, which stuns the audience.

The conclusion maintains Thalheimer’s minimalist aesthetic—no chariot, no spectacle, little closing commentary. Medea, in a simple black dress, picks up a trench coat that has been lying at her feet, walks quietly to the end of the platform, and exits. The chorus, on the level below her, has no closing ode but only two lines: clearly the gods have no duty to explain what may occur, and whatever comes to pass is never what is expected. Upon this dark note, darkness descends.

I had seen the second Theatertreffen offering, Herbert Fritsch’s Murmel Murmel, last year in Berlin, but the second viewing was just as delightful as the first. Fritsch is today one of the most popular directors in Germany and arguably the greatest director of farce in today’s theatre anywhere. This is his third consecutive year of invitation to the Theatertreffen, beginning in 2011 with an invitation to two of his productions, an honor given to very few directors. His first invited production, a zombie version of Ibsen’s A Doll House, I still remember as both one of the funniest stagings of Ibsen I had ever seen, and, surprisingly, one of the most revealing of the hidden dynamics of the play. On the whole, Fritsch has worked with older dramatic texts, some comic and some not, but Murmel Murmel takes its inspiration not from a play but a book, and a very strange one indeed. In 1974 Fluxus artist Dieter Roth published a 180 page book which consisted of the repetition of a single word, “Murmel.” The word means marble in German, but it closely resembles the verb murmeln, or “murmur,” traditionally applied to the meaningless babble of an onstage crowd

Fritsch has ingeniously adapted Roth’s Fluxus book into a Fluxus production, but where the book was devoid of content, Fritsch’s overflows with content, but it is totally theatrical, not narrative. For an hour and twenty minutes his eleven actors say nothing but the word Murmel obsessively and repeatedly, but in every sort of tonality—singly, in dialogue, in chorus, in a rapidly repeated uninflected undertone, in a single defiant shout, as the lyric of a pop song or an operatic area. As they repeat it, conducted often by a gentleman in military uniform in the pit, they execute a frenetic and constantly varied sequence of physical actions, reminiscent in general of the slapstick routines of silent film comedy, which is a strong influence in much of Fritsch’s work. The physical control and acrobatic of these performers, often suggesting a Dadaist ballet, is simply stunning. They hurtle about the stage, interact with a set in as constant and frenetic motion as themselves, and repeatedly fall into and climb out of the pit, all with equal speed and ease. The constantly moving set (also the work of Fritsch), is composed of elements each painted in a single color like the decorations in a child’s play room. It consists of teasers above and wings on either side that keep moving back and forth, up and down, constantly hiding and revealing actors, and altering the dimensions of the playing space, sometimes closing in on all sides to confine or even threaten to crush the actors caught between them. Behind all of this is a white backdrop that allows the action to continue from time to time in the silhouetted figures of actors behind it. A music score, partly performed live by the conductor in the pit and partly taped, was created by Ingo Günther and significantly contributes to maintaining the frenetic pace onstage. The enthusiastic audience greeted the entire evening with almost continuous laughter and applause, and although the applause following German productions is generally more extended than in the United States, this was unusually long—more than fifteen minutes of applause for an eighty minute production, which suggests something of the enthusiasm for this impressive work.

When I first started attending the German theatre some thirty years ago, I was struck by the length of the productions—four and five hours being a quite common running time. Toward the end of the century there was an abrupt change, with many of the emerging directors, like Thalheimer, presenting cut-down, rapidly played, intermissionless productions so that classics like Ibsen and Chekhov were often seen in stagings of two hours and under. Today both approaches are commonly seen, as was evidenced by the first four selections of the Theatertreffen. Medea was performed in two hours, Murmel Murmel, as I have noted, in just eighty minutes. The next two offerings, both stagings of very large and multiplotted novels, provided a sharp contrast, each running nearly five hours.

The first was Luc Perceval’s stage adaptation (with playwright Christina Bellingen) of Jeder stirbt für sich allein (Everyone Dies Alone), the international best-selling novel published in 1947 by Hans Fallada. This, one of the first anti-Nazi novels to be published in Germany after World War II, was based primarily on the true story of a German couple who between 1940 and 1941 distributed leaflets in Berlin condemning the Nazis and infuriating the authorities. Fallada interweaves their story with the lives of those around them, creating a panorama of the cruel and oppressive conditions within a regime already collapsing but sustaining itself by fear and brutality.

Perceval, originally from Antwerp but since 2000 based in Germany, has long been a leader in the German theatre. He is now the head director of the Thalia Theater in Hamburg, one of the three or four most honored theatres in Germany, where he produced Jeder stirbt. Although he is particularly well known for his modernization of the classics, Perceval has twice produced important stagings of the novels of this early twentieth century German author. In 2009 he staged an earlier Fallada novel, Kleiner Mann, was nun? dealing with the effects on a group of everyday Germans of the world economic crisis of 1929. This production was also invited to the Theatertreffen.

In keeping with the minimalist trend now clearly operating on the German stage, Perceval’s designer Annette Kurz has designed a simple, but extremely powerful setting, which remains unchanged throughout the evening. Upon the essentially empty playing area there is a single element, a simple, unadorned rectangular table which during the evening is sat upon, lied upon, and placed upright to form various backings and barriers. At the rear of the stage is the dominant visual element, an enormous relief map, rising from the stage floor into the flies, apparently of Berli viewed from above, containing hundreds of buildings which are composed of found elements—boxes, bits of machinery, purses, briefcases, and countless unidentifiable scraps of material. A pile of similar material lies at the base of the map, apparently either left-over material or material than has fallen off of the construction above. At first I took this striking construction and its elements to suggest that Berlin was built up (as was this story) from fragments of everyday life, but I later consulted a review of the original production in Hamburg and discovered that much of the found material utilized in the construction of the map, thousands of individual objects, was actually boxes, toys, books, and personal items from the 1940s, recovered from flea markets and junk shops, thus adding another dimension to its appropriateness.

One effective touch utilized throughout the production is the depiction of the stage space as a flow of characters, as on a Berlin street, all crossing from one side of the stage to another, but always as individuals, each absorbed in their own activities and traveling at their own rhythm, some running, some strolling, some moving furtively, glancing about to check their surroundings, others striding with assurance. These form a kind of living backdrop which supplements the brooding relief map against which the major plots develop. At the center of these are the couple Otto (Thomas Neihaus) and Anna Quangel (Oda Thormeyer) the meaningless death of whose son in the war inspires them to begin their act of civil disobedience. Their anonymous postcards terrify their already frightened neighbors and drive the Gestapo commander Prall (the incomparable Barbara Nüsse) to become obsessed with their capture. He assigns Kommissar Escherisch (André Szymanski) to the case, and the center of the action is this pursuit. All the many subplots, each reflecting the corruption, the cowardice, and the bravery of the individuals caught in this fearful time, are carefully tied back to this central action. In the middle part of the production, the focus shifts when Escherisch is for a time misled into thinking that a rather dimwitted if good-hearted malingerer, Enno Kluge (Daniel Lammatzsch) is the culprit he is seeking, and when he discovers his mistake, encourages Kluge to kill himself. All ties back to the central action, both narratively and emotionally because Escherisch gradually evolves as a character from an opportunistic Nazi sympathizer to a (still silent) sympathizer to the cause of the Quangels. The production does not end with the execution of the Quangels in their dark prison cell, however, but in the open countryside, where survivors of the horrors we have witnessed gather upon the ever-present table, now a country cart, and ride off together into what must surely be a better future.

The staging and dramatic cutting are powerful, but the honors of the evening go to the superb cast, giving new evidence both to the power of the Thalia ensemble and to Perceval’s reputation as an inspirer of actors. The presentation choice is to have the actors remain always in character but to mix their actual lines with accompanying text, a blend which I first saw in the famous Nicholas Nickleby production by the RSC, and in the hands of good actors can be remarkably affective. The already mentioned leading characters, especially Nüsse and Szymanski, dominate the evening, but as is often the case with the best German ensembles, the performances down to the smallest part are powerful and richly nuanced. The placing on stage of a novel, especially a large and complex one, is a tremendous challenge, but one which Perceval and his excellent company have taken on with admirable success.

The same unfortunately cannot be said for the other monumental stage adaptation of the festival, Sebastian Hartmann’s five-plus-hour staging of War and Peace from Leipzig. I came to this production with high expectations, not only because of the success of the Fallada adaptation but because I had much enjoyed previous Hartmann productions such as his 1999 Ghosts and his 2001 The Robbers. During the late 1990s he worked for a time with Frank Castorf, with whom he is often compared, but they share mainly a willingness to take great liberties with the classics, often by the introduction of contemporary music and references, as well as mixed media and popular, often rock music. Hartmann is rather softer, however, one might say more romantic, and more inclined to create striking visual images.

All of this can be seen in his War and Peace, his final production at the Leipzig theatre, which he has directed since 2009, amidst continuing controversy over his unconventional stagings. Certainly this controversy continued with the present production. During the Leipzig performances (and subsequent showings at the Ruhr Festival and elsewhere) only about one-third of the audience was reported to have stayed until the end. Berlin Theatertreffen audiences are made of tougher stuff, however, and although the audience was clearly diminished by the end, the majority of them remained, as did I, although on this occasion, I distinctly envied those who departed earlier.

To begin with, Hartman makes no attempt to present the story, although he plays individual scenes and debates, often in several variations and with different actors. His fourteen member ensemble begins with a choric chant setting the scene and then distributes roles in each new scene. Thus most of the cast at one time or another play Andrei, the central figure. Particularly striking here is Heike Makatsch, who plays one of the most impressive of Andrei’s death scenes on a steeply raked stage, sliding slowly downward as she attempts to hold death at bay. A word must be said about the stage, a monumental construction designed by Hartmann and Tilo Baurgärtel consisting of two giant plates, each filling the stage, one suspended from the flies and often used to show film or video images, or variously colored ribbon light messages, the other, the major acting area, supported by an enormous metal pole in the center of the stage, upon which the entire area can tilt forward or back, from side to side, or at a variety of other angles, creating a constantly shifting physical space. It is the sort of technological theatre that one could only dream of in America but which is easily created in any large German house. The kind of theatrical space this device allows strongly suggests a number of the stages created by Olaf Altman for Thalheimer or by the ingenious Andreas Kriegenberg, who normally creates his own designs. What struck me here was that although powerful images were from time to time created on this stage, the physical properties of the stage itself were not in any way organically related to the production as a whole, in the way that they inevitably are in Altmann or Kriegenberg. In short, impressive as the machinery was technically, it seemed to me ultimately a great deal of money wasted.

Returning to the actors, most handle the multiple and rapid shifts in character extremely well, though when Hartmann decides to present scenes of low comedy, which he does more and more frequently as the evening goes on, their attempts seem (perhaps calculatedly) almost painfully awkward and amateurish. Typical was an extended (at least five to ten minutes) slapstick clown show debate on the existence of God by two of the women in fake mustaches that exhausted itself in about thirty seconds and made one long for the sophisticated and professional farce scenes of Fritsch. The final third of the performance is composed entirely of a series of scenes of this kind, exploring, often in the crudest manner, themes extracted from Tolstoi’s work, without maintaining any connection to the work itself. The theme of sex for example, is addressed by an extended sequence involving large cardboard boxes in some of which imitation blow-jobs are enacted (built around racist jokes involving a sex-crazed turbaned actor purportedly from Mumbai) and culminating in a sexual act between two of the boxes, carried out by a postal tube protruding from one of them that enters the other, much to the delight of the Berlin audience.

This series of variety acts—including literal clowns, Lewis-Carroll-type white rabbits, mechanical ballerinas, nude couples, imitation Napoleons, actors howling like wolves, and a deformed half-nude female figure crawling slowly across the stage as if in an early Robert Wilson piece—ended with the entire cast coming out into the audience and confronting individual members with questions about whether they believe in chance, destiny, or great men. The few responses that this elicits are ignored. This is followed by an eight-minute video by Baumgärtel which essentially gives the illusion of rushing headlong through endless corridors of varying architectural styles. Both the graphics and the technique are so crude that they would put to shame any beginning digital art student in the United States, which I must assume was the intention. Occasionally the headlong rush through corridors is varied by a headlong rush toward a cartoon vagina or past open coffins that emit cartoon upwardly speeding ghosts. Finally one such coffin stops as the corridors continue to rush by and the fourteen cast members seem to climb into it, waving goodbye to us as they speed off down the corridors. Most the audience seemed delighted and gave the production extended applause but for myself I had to admit that it seemed to me to represent the worst excesses of what many Germans condemn as Regietheater, theatre in which directorial tricks hijack the production.

Now that Hartmann’s administration at Leipzig has ended there is considerable speculation in Berlin that he may be selected as the successor to Castorf, who has directed the major Volksbühne since 1992, a remarkably long tenure for a Berlin theatre director. Unquestionably Hartmann, if this occurs, will carry on the iconoclastic, post-modern reputation of Castorf, though in his own direction. Despite my uneasiness at this latest production, I think this would be a stimulating addition to the Berlin scene. It is clear that Hartmann, always a divisive figure in comparatively conservative Leipzig, will find a much more supportive public in Berlin. Whether that affects his work for good or ill would prove an interesting process to observe.

Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Strasse. Die Stadt. Der Überfall, directed by Johan Simons. Photo: Courtesy of Munich Kammerspiele.

Although widely regarded as Germany’s great living playwright, Elfriede Jelinek creates texts of unparalleled difficulty for directors, vast chunks of material usually without stage directions, indication of speaker, or even in some cases punctuation. They require a director to find and carve out his or her own theatrical text from this material. A number have risen to the challenge with powerful results, among them the Dutch director Johan Simons, formerly artistic director of the National Theatre of Ghent and at present artistic director of the Munich Kammerspiele. For the centennial of that theatre, Jelinek created and Simons staged a new piece, Die Strasse. Die Stadt. Der Überfall (The Street. The City. The Raid) clearly dedicated to the city of Munich (in fact it has not been published; the 129-page text from which Simon has carved his play remains in the sole possession of the Kammerspiele).

Jelinek takes her inspiration from the fact that the Kammerspiele is located on the Maximilianstrasse in Munich, one of the world’s great fashion streets. The performance is essentially a meditation on the hollowness and necessity of fashion, how humanity and the mode seek in vain to find a reality, a center, in the other. Like all of Jelinek’s work this is an indictment of capitalism, but a surprisingly warm and gentle one overall. The evening is divided into two parts and many critics suggested one should leave at the break, but I found each equally theatrical and fascinating. The first part is the more general commentary on the hollowness of fashion, somewhat repetitive, but always engaging, thanks to the comic and dramatic skills of the six men (Stephan Meier, Hans Kremer, Steven Scharf, Maximilian Simonischek, Marc Benjamin, and Stephan Bissmeer), who appear in various stages of dress and undress, but always in drag and high fashion. They surround the equally fashion obsessed Sandra Hüller in what they themselves call an “orgy” but which is truly only an orgy of vanity and hollow self-seeking display. There is a freezing emotional coldness at the heart of their actions, beautifully captured by stage designer Eva Veronica Born, who covers the stage at the beginning with several inches of bits of ice, rather like some of the covered stages of Pina Bausch, through which the high-heeled actors must make their way. The glittering ice, like diamonds, but melting away from the heat of the stage lighting as the evening progresses, is a stunning metaphor for the ephemeral subject of the evening. A part of the audience is seated on stage so that this ice-covered playing area has spectators looking across at each other from two sides. Access to the stage is primarily from an enclosed opening with stairs going down that serves, effectively, as the gate to death in the later scenes. Above the stage hangs a huge white globe, and on one side, opposite the stairs, is an enclosed glass area, resembling, and often referred to as a small boutique, behind which sit the five musicians whose music accompanies much of the evening and who provide accompaniment for the occasional somewhat Brechtian songs that punctuate the action.

In the second part the focus shifts from the general to the particular, and the production strongly shows its Munich roots. The focus now shifts to a central figure of the Munich fashion world, Rudolph Moshammer, played in a grotesque parody mask and wig (both of which he eventually tears off) by Benny Claessens. The near-legendary Moshammer’s boutique “Carnaval de Venise” was at the heart of Maximilianstrasse’s fashion world, creating designs for wealthy men from furs, cashmere, and silk. Moshammer was an eccentric, but munificent figure, murdered in 2005 by a young man from whom he had allegedly sought sexual favors. The second part is filled with details of Moshammer’s life, career and death, including references to the dog Daisy, who inherited his estate, the cable with which he was strangled, his relationship with his mother and his male companions, and his irritation that few people attended his funeral (actually there were some 10,000) because they were all off taking their winter vacations at the Tyrolian resort of Kitzbühel. One can see how non-Munich critics would find all of this quite self-indulgent, but I found this microcosm balancing the macrocosm of the first part quite effective, and although I was not convinced by Moshammer’s repeated claim that his death was also the death of the street, of the city, and of the world of fashion they embodied, I still found the extended elegy on the inevitable death of this hollow world quite moving.

Jérôme Bel is internationally known as one of Europe’s most innovative choreographers, and one of the leaders of the “non-dance” movement in new French dance, which emphasizes multimedia work, performance in unconventional spaces, and movement outside the traditional dance vocabulary. In 2012, Bel was invited to create a piece with the Theater HORA in Zurich, a professional company composed entirely of actors with mental disabilities, primarily Down’s Syndrome. Although their past productions have been of familiar authors like Shakespeare and Conrad, Bel decided instead to present the eleven actors with whom he worked in their own characters, creating work based on themselves and their professional lives. The result was Disabled Theater, a performance piece that premiered with enormous success in Brussels, and then went on to major festivals and other European venues throughout 2013 and to New York toward the end of this year.

For most of the evening the eleven performers, ranging in age from eighteen to fifty, stand or sit in a row of chairs upstage, while a narrator/translator sits at a downstage table to the right, introducing the audience to the performance. First the narrator outlines the history of the project and asks the actors to introduce themselves. Their brief autobiographical statements always include their profession: actor. In the major part of the evening, each performer presents a dance piece he or she has created themselves, to a musical accompaniment they have chosen. From a conventional technical point of view some of these are moderately skilled, while others are most commendable for their determination and dedication. All, however, receive hearty applause from the audience, although not unmixed with a certain unease at the entire process. This unease is articulated more fully in a concluding section of the performance where the narrator asks each performer to talk about their experience in creating and performing this piece. Most speak positively of the experience, but several express the concerns of family members and others that this public display was not so much a celebration of their triumph over adversity as a kind of “freak show.” Unquestionably the work, and the performative assumptions behind it are as disturbing as they are moving. Forced to confront the generally suppressed recognition of notions of normality and abnormality, of the public and the private, the audience found this work the most controversial and unquestionably the most memorable and unique in this year’s festival.

British director Katie Mitchell, whose multimedia Wunschkoncert was selected for the 2009 Theatertreffen (see WES, 21:3) returned this year with a similarly constructed Night Train, based on the 1984 poetic prose novella Reise durch die Nacht by Friederike Mayröcker. Mitchell began experimenting with a mixture of live action and live video with her 2007 adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves in London, and has continued to refine that technique in a series of works presented since then in Germany and England. In each of these, what seems to be a fairly conventional video film unrolls seamlessly on a screen above the stage, but in fact the audience sees on the stage below how many disparate elements are combined to create this illusory image. In this production the setting beneath the screen was essentially a long railway car, created by designer Alex Eales, with some compartments open, others closed, and others seen only through windows.

This railway car is in fact essentially a kind of film set, however, with scenes played in various parts of it and recorded by live video cameras for projection above. The audience thus simultaneously sees the filmed action and its creation within the illusory set. The flickering lights outside the windows as another train passes or the passing landscape (created by Leo Warner and faithfully suggesting the Europe of the novel’s creation) are revealed as projections or mechanical devices, whose creation we see onstage at the same time that the video camera is recording them as filmic reality. There are also flashbacks within the film to the life the heroine Regina (Julia Wieninger) has left behind in Paris as their sleeper car rolls toward Vienna, these also created within small settings embedded in the car and filmed as if they were part of another location.

The constant moving to and fro of cameramen, technicians, and actors relaxing between scenes or preparing for their next entrance creates a constant bustle in the actual stage area which could easily become confusing were it not for the fact that the steadily progressing film that is being created is always above the action, directing the attention of the viewers to how the complex movements on stage are constantly being integrated into this creation, seemingly following a natural progression but actually being simultaneously created out of disparate elements as we watch. Mitchell has found a fascinating way to reveal the actual labor and mechanics which video and film have traditionally covered in a way that increases rather than diminishes our respect for this complex phenomenon.

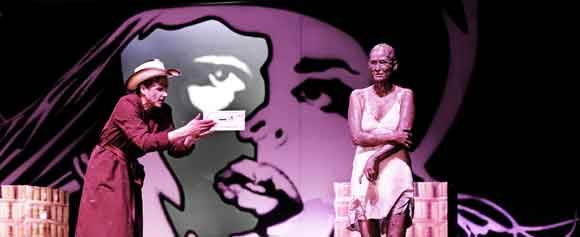

Sebastian Baumgarten’s production from Zurich of Brecht’s Saint Joan of the Stockyards aroused a certain amount of critical hostility, but not because of its conversion of Brecht into a kind of postmodern variety show, though that was certainly the general impression, with the jazz musician Jean-Paul Brodbeck providing the almost continual musical accompaniment, as if the production were a silent film, a tradition which it in fact often quoted. The complaints had more to do with Baumgarten’s decision to carry out his cartoonish visualization of the Brechtian parable not only by extreme exaggeration of many features (the “black straw hats” Salvation Army becoming huge black designer headpieces, more like those of the witches in the musical Wicked than in anything by Brecht, and the Chicago capitalists becoming literally Western cowboys whose hapless victims lurk in graffiti-coated teepees), but even more because almost all of the major characters are defined, vaudeville-style, by ethnic and racial clichés. The most protest concerned Frau Lukkerniddle (Isabelle Menke), whose husband accidently ended up as canned meat. The actress appeared in thick black face and body paint with bright red lipstick, in an afro wig and a grotesque, white, African-style dress with heavy jewelry (costumes by Jana Findeklee). Nothing in the text or the production supported this extreme choice, which, although it drew the most comment, was by no means unique. The landlord Mulberry (Gottfried Breitfuss) was played in yellowface, with a long thin mustache, continually slurping at a bowl of noodles and speaking with a “Chinese” accent. Another worker (Samuel Braun) wears a fur hat and speaks “Russian.” Baumgarten in a post-show discussion explained that Brecht regularly worked with stereotypes and that in order to truly represent the victims of capitalism in today’s global economy a variety of ethnic representatives was necessary. Moreover, similar vaudevillian stereotyping was rather inexplicably utilized with the capitalists themselves. Aside from being cowboys, which is perhaps understandable enough, the three central villains all had odd and distinctive speech patterns. Mauler (Markus Scheumann) had a strong lisp, Cridle (Jan Bluthardt) stuttered, and Graham (Lukas Holzhaugen), rather surprisingly, had a distinct Yiddish accent.

Parody and slapstick suffused the evening, pop culture references abounded, from “Lucky Luke” to “Modern Times,” to vampire and zombie movies, with at one point an enormous cut-out mask of Che Guevera in the background with an entrance through his shaded cheek. In all of this reworking, Yvon Jansen as Saint Joan rather got lost, despite her enormous black hat, while Mauler and his blue-suited cowboys carry off the production. At last Joan, frozen by the icy world they are creating, drops rigidly to the floor, her accusing finger pointing toward heaven as if the deity were also implicated in this wholesale crushing of humanity.

The stylized, cartoon-like approach was less troublesome with the settings by Thilo Reuther, using simple forms and imaginative projections to create a fantasy world full of international but especially American pop culture icons. A concluding video montage summed up these images, suggesting the rise of modern America from the 1970s onward, culminating in Barack Obama, while the groups of costumed characters (the workers in red, the capitalists in blue, and the Salvation Army members in white) were suddenly reinforced by an image of Spiderman, wearing a skin-tights suit of these same colors and backed by a huge American flag. The evening seemed on the whole as much an ironic celebration of the icons of late capitalism as a critique of it and while it was unquestionably a full evening visually, it seemed ultimately strangely devoid of any specific political content, a very strange outcome for a revival of Brecht, but perhaps not surprising at a time when the Americanization of culture, politics, and economics is widely deplored but surprisingly little resisted.

From the Cologne Schauspiel this year came Karen Hinkel’s production of Gerhart Hauptmann’s naturalistic tragedy, Die Ratten. Hauptmann’s grim tragedy of switched babies, false claims of paternity, murder and suicide, takes place in a Berlin tenement, watched over by Harro Hassenreuter, a former theatrical manager who resumes that career in the course of the play, and who gives acting lessons to several of the play’s lesser characters. This circumstance has led director Hinkel to move the play far from its naturalistic tradition into a meditation on theatricality, with characters often seemingly fully conscious of role-playing with often highly artificial mannerisms and in a decidedly non-realistic environment.

The evening begins with a sharp challenge to audience expectations. Instead of entering the front of the festival theatre which is the central home of the Theatertreffen, or going to the smaller, more intimate stage at the left end of the building, the audience goes through the large lobby and out into the garden, which normally serves as a kind of extension to the lobby, and then around to the rear of the building and through one of the rear stage doors, normally used only by theatre personnel, to discover a dimly lit space where they mix with the actors who are looking over possible costumes from racks that sit near the stage (costumes by Klaus Bruns). Since most of the actors play several roles (one, Jennifer Frank, plays four, including a barking dog) these costumes, striking though usually minimal, prove an important indication to the audience of which role they are assuming, while adding to the improvised, artificial tone of the whole. This is especially true since the selection of dress is often quite whimsical. Michael Weber plays the policeman in a spiked Wilhelmine helmet, which is arguably appropriate, but also plays the janitor in a bouffant tulle ballet skirt, which is decidedly not.

The actors not only move in and out of their roles, but also from time to time perform what might best be described as acting exercises or tryout pieces. The young theologian and would-be actor Erich Spitta (Jan-Peter Kampwirth) encouraged by the washed-up theatre director Hassenreuter (Yorck Dippe) presents a number of Shakespeare monologues, and one of the high points of the evening is an extended, highly obscene, and seemingly at least partly improvised riff on the status of women by Kate Strong, performed entirely in English. The stage design by Jens Kilian, makes no attempt at illusion. The large performing space is mostly open, and offstage actors may simply sit quietly at its edges, but it does have one fairly large unit which can be rolled about the stage and which contains the suggestion of a small room and access to a small space overhead. A few decorative elements, like a small, crude wooden crucifix, can be added, like the fragments of costume, to give the room a bit more specificity. There is also a large, downward pointing floodlight downstage which can be moved to different locations and which is used by individual actors who wish to place themselves “in the spotlight” for certain speeches. Pregnancies are suggested by false, strapped-on bellies, which ironically reinforce the concern of the drama with its confused claims of motherhood. When the guilty Mrs. John (beautifully performed by Lena Beckmann) finally commits suicide in remorse, her fellow actors surround her and solemnly cover her body with fake blood.

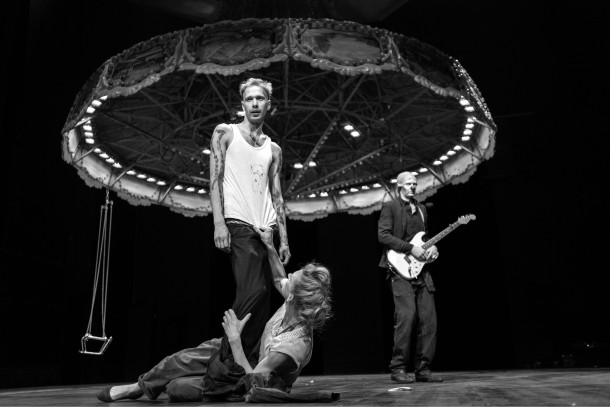

Sebastian Nübling took considerable liberties in his Munich production of Tennessee Williams’s rarely performed Orpheus Descending, but he captured in his own terms the lush exoticism of Williams and created one of the most striking and effective productions of this year’s Theatertreffen. The production opens and closes with a huge black Doberman dog standing alone onstage. Later his owner will be revealed as the leader of the town’s controlling gang, Jabe Torrence (Jochen Noch). The dog’s head is also reproduced on the jackets of Torrence’s followers, one of whom is a beefy leather clad figure who from time to time throughout the evening, circles the stage on a huge, roaring, diesel-blowing motorcycle. The distant barking of dogs throughout the evening reminds the audience even during the love scenes of the ever-present menace of these men. After the grotesque and grim cartoons of the male denizens of this Southern town come the female representatives (Annette Paulmann and Angelika Krautzberger), two blond furies, spewing vulgarities and blowing up and decking themselves in phallic pink balloon snakes.

The production is dominated by the fascinating figure of Risto Kübar as the doomed interloper Val Xavier, whom these figures will destroy. He is here interpreted in a manner as far removed as possible from the exuberant masculinity of a Marlon Brando. This is the first starring role for Kübar, an Estonian actor bought to prominence in Nübling’s 2011 production in Munich of Simon Stephens’ dark crime fantasy Three Kingdoms, a role which Kübar played entirely in Estonian. As Val Xavier, Küber speaks a mixture of Estonian, English, and Estonian-inflected German, reinforcing his role of outsider, but even more striking than his language is his physical appearance and movement. A thin, almost serpentine, snakeskin-clad, androgynous figure, constantly caressing himself and moving as if in a fluid dream, he combines features of a transsexual street hustler and a pop idol of adolescent female fantasies. A dark clad deathly double follows him about as a constant reminder of his immanent fate.

The most striking visual element of the setting is a giant carousel, which eventually fills the entire stage, but which at the beginning exists only as a large dim circular object hanging in the flies. Nübling and his designer, Eva-Maria Bauer had the theatrically inspired idea to convert the garden restaurant that Lady Torrence (played with a powerful nervous energy by the leading German actress Wiebke Puls) plans to build in memory of her father to a carousel, the construction, lighting, and eventual operation of which by the Lady and Val fills the evening and the stage. The activity of creating this fantasy item together beautifully reinforces the growing physical attraction between Val and the Lady and they slowly and carefully place and gradually illuminate the forest of lights that circle the lowered roof of the structure. In one memorable tender scene, the lovers ascend, approaching each other on a ladder and at last disappear together into the illuminated dome above.

At last, the carousel completed, Val and the Lady enjoy a brief giddy ride, a moment of happy escape from the surrounding darkness, but it is only a moment. Lady Torrence’s husband enters and shoots her, leaving her corpse dangling from the seat on the gaudy carousel, while Val is taken off to his death. At the end only the grim Doberman remains on stage, the Cerberus to this dark hell.

, Sidney E. Cohn Professor of Theatre at the City University of New York Graduate Center, is the author of many articles on theatrical theory and European theatre history, and dramatic literature. He is the 1994 recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for dramatic criticism and the 1999 recipient of the American Society for Theatre Research Distinguished Scholar Award. His book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, which came out from University of Michigan Press in 2001, received the Callaway Prize. In 2005 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Athens. His most recent book is The Theatres of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia with Khalid Amine (Palgrave, 2012).