The Ruhrfestspiele in the town of Recklinghausen is not one of Germany’s largest theatre festivals, but it is one of the oldest. In the aftermath of World War II, theatres in Hamburg were faced with the prospect of having to shut their doors due to a lack of coal in the winter. They sent a delegation down to the Ruhr valley, a major coal-producing region, to see if they could find a way around rationing rules. Surprisingly, miners were sympathetic and shipped up enough coal to keep the theatres open a little longer. In gratitude, the theatres sent troupes down during the summer of 1947 to perform for the miners, using the slogan “Art for Coal.”

Every year since, Recklinghausen has played host to an increasingly international group of theatre companies that in May and June turn the small town into a world stage. Today, the Ruhr region has transitioned away from its traditional mining-based economy, and the festival has become much more institutionalized than it was in those chaotic post-war years. Recklinghausen no longer produces as much coal, but it now boasts a state-of-the-art festival house with two main stages. This year it opened a new performance venue in a former industrial site in the suburbs. A vibrant Fringe Festival also comes to Recklinghausen each year, performing in tents in the city park outside the festival house.

The theme for this past summer’s festival was “Aufbruch und Utopie,” or “Departure and Utopia.” While productions do not have to adhere closely to the theme, the festival does try each year to draw connections between its theatre offerings and a writer or period from the past. This time, the festival wanted to examine the powerful cultural shifts taking place at the beginning of the twentieth century, when artists and writers were trying to create new worlds. A special exhibit in the festival house gave a month-by-month history of events in literature occurring in 1913. Another smaller exhibit highlighted some of the early twentieth-century writers represented in the Ruhrfestspiele this year.

The Eifman State Academy Ballet of St. Petersburg provided one of the festival’s more high-profile international productions, Red Giselle. The ballet tells the story of the Russian ballerina Olga Spessivtseva, who is best known for dancing the title role in Giselle, and who began her career, incidentally, in 1913. In tracing her rise and fall, the piece uses both en pointe classical ballet and more modern dance forms. Boris Eifman provided the choreography, which was set to music by Tchaikovsky, Schnittke, and Bizet. In telling the story of Spessivtseva, Eifman also tells the story of artists throughout Russia during the early twentieth century.

At the end of the first act, the star ballerina flees the chaos following the Russian Revolution. The audience then sees her life in the West, and there is a wonderful scene where her former lover’s disembodied head appears, peeking through the stage curtains. She tries to stroke his face, but then gets sucked in and has her own head pulled behind the curtains. When her head emerges, it is covered with red cloth, which unfurls to reveal a huge flag-shaped piece of red fabric that drapes around her body. From that point on, she descends into depression and madness.

Red Giselle is one of Eifman’s more established works, having premiered back in 1997, but the dancers kept the production fresh and exciting. Last year, the company brought its more recent ballet Onegin to Recklinghausen, and many in the audience were clearly anticipating this year’s production. Judging from the excited chatter at intermission and after the performance, they were not disappointed.

Another international offering was Les Visiteurs du Soir’s Le Navire Night, a performance billed as a dialogue for voice and cello. French actress Fanny Ardant gave a lush rendition of a story by Marguerite Duras about a passionate love affair that takes place over the telephone. The performance was in French with German supertitles, while American cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton provided haunting music. The one-night engagement banked on the star-power of Ardant, who is known for her distinguished film career. In contrast to the visual medium that made Ardant famous, this production contained no set and virtually no movement, focusing entirely on the aural experience. Though this might have been disappointing to those who came to “see” a film star, it was appropriate for the Duras story, which is an ode to the power of the human voice.

Much more visually interesting (though not without controversy) was Der Tod in Venedig / Kindertotenlieder. This co-production by Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz Berlin and the Théâtre National de Bretagne Rennes brought together scenes from Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice with Gustav Mahler’s settings of poems by Friedrich Rückert. Director Thomas Ostermeier deftly integrated video into the performance. A camera team walked around the stage getting close-ups of the actors, and these were projected onto a large screen above the stage. Though this sometimes divided the audience’s attention, it was successful at turning subtle acting moments into monumental events.

At the beginning of the play, the boy Tadzio appears in a traditional sailor’s suit as he is described in the book, but he is playing a hand-held video game (obviously absent from Mann’s 1912 novella). The camera zooms in on the game before moving to other things. The audience sees Tadzio’s governess, his sisters, and Mann’s protagonist, Gustav Aschenbach, all with the viewer receiving an almost voyeuristic level of intimacy. The close-up device is used particularly effectively when Aschenbach and Tadzio exchange a long knowing glare at one another, and again when Aschenbach undergoes his cosmetic treatment in a futile attempt to appear younger. The massive image of the actor’s face literally hangs over the action, drawing attention to his embarrassment and bewilderment.

Der Tod in Venedig / Kindertotenlieder, directed by Thomas Ostermeier. Photo: Courtesy of Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz Berlin.

This production also deals head-on with the issue of pedophilia in the story. At one point, the narrator who has been reading Mann’s words stops the show and asks for the house lights to come up. He reads aloud one of the more provocative passages from Death in Venice. The camera then zooms in on a newspaper article discussing the controversies surrounding “perversion,” and the audience gets to see that Mann’s book is cited in the article. The issue now confronted, though not resolved, the play returns to its regular style.

When Aschenbach starts worrying about the cholera epidemic in Venice, he speaks to a waiter at the hotel. This scene is barely whispered (and for some reason, performed entirely in English, in spite of the story’s Italian setting and German protagonist). The waiter asks him repeatedly to sign his bill. Aschenbach pauses, but finally signs it. He asks the waiter if there is a problem with disease in the city. The waiter quietly backs away, mumbling half-hearted reassurances.

At the premiere, the scene was performed so quietly it prompted a heckler in the back of the theatre to yell at the actors. Later during the same performance, two people toward the front of the theatre showily got up and left, forcing an entire row to stand as they made their way to the exit. Clearly, not everyone in Recklinghausen appreciated this type of avant-garde performance.

At the play’s climax, Tadzio’s sisters enter in their nun-like dresses at the back of the stage and take off their shoes. As they move downstage, they begin dancing, both fiercely and sensuously, with Dionysian passion. They shed their nun-like gowns and dance naked with one another, fighting with each other and mercilessly pulling at each other’s bodies like crazed Maenads. While all this is happening, dark objects drop from the flies and float down to the stage. These resemble pieces of paper or plastic, or perhaps ash. The plague, and all of the Bacchic forces it represents in Mann’s story, appears to be raining down on Venice. It provides a dramatic conclusion to a highly innovative production.

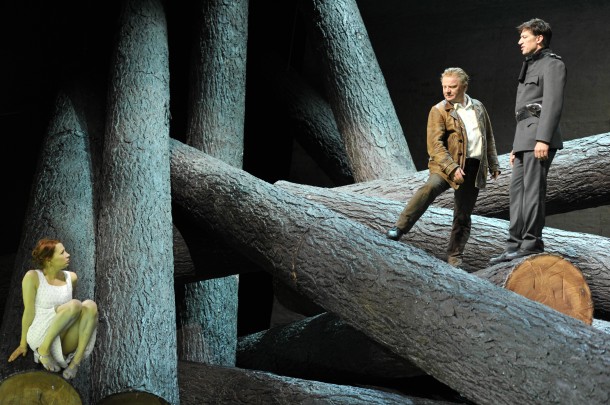

There are inherent difficulties with loading in a large set for a few performances at a festival. That in no way daunted Munich’s Residenztheater, which staged Karl Schönherr’s intimate drama Der Weibsteufel with a massive set that dwarfed the play’s three actors. Designer Martin Zehetgruber created a jumble of massive logs that sloped across the stage and intersected one another at harsh angles. Under the direction of Martin Kusej, the actors then walked, stumbled, and climbed across the logs. The psychosexual web woven by the unnamed man, his wife, and the young officer in Schönherr’s play resonated with the complex and dangerous-looking mass of timber on stage, which simultaneously called to mind ties to the earth and humanity’s exploitation of natural forces.

Karl Schönherr’s Der Weibsteufel, directed by Martin Kušej. Residenztheater München, Recklinghausen, 2013. Photo: Hans Jörg Michel.

If for nothing else, the actors deserved their standing ovation for managing to navigate their ways across the set, intimidating, fighting, and seducing each other, all the while managing somehow not to break their necks. Zehetgruber’s fallen forest provided them with virtually no flat surfaces on which to stand, though there were a few handle holds to aid in some of the more steep ascents. The final scene, where the officer kills the man with his own knife, was acted out downstage in front of the logs. This way, the actors could at least perform the climax without having to navigate giant tree trunks. The set, especially under the harsh lighting designed by Felix Dreyer and Tobias Löffler, remained an ominous presence in the background.

What was most interesting was what came following the man’s death. After the woman told the officer he was now alone, she proceeded to climb up the logs, ascending as if into the heavens. It added a bit of a feminist twist to a play that contains a rather uncomfortable amount of misogyny. Birgit Minichmayr, performing the title role (which is generally translated as “The She-Devil”), had more of angel than devil about her. She clearly elicited sympathy for a woman dominated by two dangerous and frightening men.

The smaller theatre in the festival house cannot accommodate an entire felled forest, but that didn’t stop some creative designers from using it in very interesting ways. Of particular note was the versatile set designed by Christoph Rasche for Die Hose / Bürger Schippel, the Ruhrfestspiele and Staatstheater Nürnberg’s mash-up of two Carl Sternheim comedies adapted by David Mouchtar-Samorai. The walls of the set were filled with photographs, some in negative, of various respectable members of society from throughout history. This served as a constant reminder of the world the would-be gentlemen in the play wished to enter. At the rear of the stage was a circular door in this wall of respectability. The door could be opened or sealed off at various times, sometimes granting entrance, and sometimes as a means to expel interlopers.

The piece alternated between scenes of the two Sternheim plays, with actors from Die Hose playing parallel roles in Bürger Schippel. Louisa von Spies, for instance, played both the put-upon Frau Maske from Die Hose and the enchanting Thekla Hicketier in Bürger Schippel. Thomas Nunner played both Theobald Maske and Paul Schippel, who according to the production notes were intended to merge into a single face. In fact, toward the end of the play, the characters of Maske and Schippel did start to merge. Nunner did a wonderful job expressing his confusion, as he became simultaneously both men.

Carl Sternheim’s Die Hose / Bürger Schippel, directed by David Mouchtar-Samorai. Recklinghausen, 2013. Photo: Marion Buehrle.

At the end of Bürger Schippel, the proletarian Schippel is welcomed into respectable society. Even the prejudiced goldsmith Tilmann Hicketier is forced to take his leave politely, with the line, “Auf Wiedersehen, lieber Herr Schippel.” In this version, however, Nunner quickly goes back and forth between his two characters at the end. When it comes time for the conclusion of the Bürger Schippel plot, he is presented with the crown of laurels Schippel wins and greeted as “lieber Herr Maske.” The merging of the two characters is finally complete.

This was a very earnest production, showing the true human emotions behind Sternheim’s characters. That sometimes took away a few laughs, but it made up for it in emotional intensity. Nunner’s character at the end seemed to have truly grown, even though, as in the original plays, the portrayal of Maske/Schippel remained ambivalent. If anything, the merged ending further complicated the audience’s response to Maske and Schippel. Sternheim’s anti-heroes became sympathetic, but not fully redeemed.

Also in the smaller theatre was Bertolt Brecht’s Die Kleinbürgerhochzeit, a co-production between the Théâtre National du Luxembourg and the Saarländischen Staatstheater. For the first part of the play, director Dagmar Schlingmann had the entire cast cramped in a long, narrow room created by scenic designer Sabine Mader. There was just enough space for the wedding guests to sit behind one side of a long table, making the scene reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. When guests wanted to move around, they had to crawl over one another, which they managed with great comic effect. Adding to the outrageousness were ridiculous 1960s-era costumes designed by Inge Medert.

Downstage from the dining room was a sloping platform, and below that a flat area where the dancing took place. When the bride and groom danced with other guests in an attempt to make one another jealous, the performers went wild, calling to mind some of the excesses of the sexual revolution. The groom’s lascivious dancing was so over the top that at one point he fell off of the stage and into the audience. The production found even more comic potential in the groom’s shoddily built furniture, which fell apart right on cue. The final offstage collapse of the bed at the end drew loud guffaws from the audience.

Much of the action was slowed down and drawn out, stretching Brecht’s slight one-act play into more than an hour. This allowed the actors to find moments of seriousness in the text that might not be readily apparent. Indeed, the production might have been somewhat weightier than Brecht originally intended the play to be. Nina Schopka, as the friend of the bride, was not just a humorous vamp, but positively frightening in her aggressive sexuality. The bride and groom’s reconciliation at the end was also played as highly ambiguous, with their future very much in doubt.

The Ruhrfestspiele’s new theatre, Halle König Ludwig, is a converted industrial space that is unfortunately out in the middle of nowhere. The festival runs a shuttle service, but only for certain performances, and it must be requested at least five days in advance. Three city buses stop in the general vicinity of the theatre, running with varied frequency. For the inaugural year of the space, the festival had not even installed restrooms, instead providing temporary facilities in a trailer in the parking lot. Fortunately, the space is beautiful in its bare simplicity, making up for the other inconveniences.

One of the shows premiering in the space this year was Deutsches Theater Berlin’s production of the Kleist-award-winning play Brandung by Maria Milisavljevic. Though she is of Croatian heritage, Milisavljevic grew up in Germany and currently resides in Canada. Her play revolves around a group of Croatian young people living in Germany. After one of them mysteriously disappears, her friends become increasingly concerned and attempt to track down what happened to her. Director Christopher Rüping gives the audience an ominous clue at the top of the play, when the cast members don fox masks and menacingly surround the performer who provides live music for the production.

The set designed by Jonathan Mertz appeared to be a large window with numerous small panes of glass suspended above the stage and very much in keeping with the industrial feel of the theatre. Water slowly dripped down from the window onto the stage, creating puddles that were supplemented by buckets of water splashed around by the cast. As the performance went on, however, it became clear that the panes of glass were actually pieces of ice that slowly melted and sometimes crashed to the ground during the show. As the play is a thriller, whenever the ice fell there was a good chance it would be at a tense moment, making the audience jump. At one point in the play the characters turned their anger on the set behind them, punching out most of the panes of ice. The mostly empty frame still hung in the background, though, leaving the stage littered with water and ice chunks.

Another prominent feature of the set consisted of three microphones hanging from the ceiling. The performers occasionally grabbed the microphones and spoke into them, especially when re-creating telephone dialogue. They also occasionally re-donned their fox masks or made use of seemingly impromptu disguises to take on the roles of other characters. Though the audience eventually does find out what happened to the woman who disappeared, the play is more interested in the increasing anxiety and despair caused by her disappearance. Milisavljevic’s heart-rending portrait of the three friends overshadows any plot twists she introduces in the final moments of the play.

Maria Milisavljevic’s Brandung, directed by Christopher Rüping. Recklinghausen, 2013. Photo: Arno Declair.

As is often the case with theatre festivals, some of the best productions at this year’s Ruhrfestspiele were Fringe performances on the festival’s periphery. My personal favorite was Heute: Kohlhaas, an adaptation of Heinrich Kleist’s novella Michael Kohlhaas acted out by five performers in clown make-up. This co-production by the AGORA Theater in Belgium and Germany’s Theater Marabu skillfully used music, puppetry, acrobatics… even unicycle riding! Director Claus Overkamp seemed endlessly inventive, constantly coming up with new methods for telling the story. The performers should also be commended for their willingness to fully commit to some ridiculous stage business, which always worked due to a total embracing of the production’s outrageous aesthetic.

Though the Fringe festival billed Heute: Kohlhaas as appropriate for older children, some of the play’s representations of sexual violence might have been too much for younger audiences. When Kohlhaas’s enemies take his horse away toward the beginning of the show, they simulate raping a toy horse, both anally and orally. After the violation of the horse (which also has its ears and much of its skin ripped from its body) three men pose standing over the horse in a manner reminiscent of pictures from Abu Ghraib prison. In a creepy final touch, they get a member of the audience to photograph them. The fact that younger audience members continued to watch gleefully throughout these atrocities is perhaps not flattering to human nature.

An even more disturbing scene occurs later in the play when Kohlhaas’s wife volunteers to carry his petition to the authorities. According to the Kleist story, she is struck in the chest with a lance’s butt. In this version, a despicable guard with a long pole harasses her shamelessly, at one point jiggling her breasts with the lance while she has no choice but to stand there, stone-faced, and endure the humiliation. He places the lance between her legs, and after he delivers a particularly violent thrust, she grabs the pole. When he pulls it out, it is covered with blood, and the wife subsequently dies.

This is what sends Kohlhaas over the edge in a city-burning rage. At one point, performers toss small puppets over the back of the set while one of the actors, representing Kohlhaas and his men, bats at them with a club. The puppets go all over the stage, and some fly into the audience, again to the joy of excited children. During another scene, cast members pass out balls to the audience and urge them to try to knock down a puppet representing Kohlhaas’s arch nemesis. Police puppets then arrive to protect him from the crowd, and when some of them get knocked over, the actors set them back up again and continue to urge the children (who need no urging) to continue their assault on the police.

One interesting choice was to not have any single actor play Kohlhaas himself. Instead, performers read aloud his various petitions or recited his lines in a deadpan tone directly into a microphone. Instead of distancing the character from the audience, the device tended to make the audience associate themselves even more closely with Kohlhaas. The wrongs committed against him could easily have been done to us, and his revenge gave vent to our own righteous indignation. Political references, including the horse/prisoner scene and an authority figure giving a Nazi salute, only added to the audience’s outrage, helping them to side fully with Kohlhaas in spite of his rather excessive revenge.

Perhaps the most inspired moment occurred when the stage lights went out and the light board operators sitting behind the audience took out flashlights, searching furiously for the source of the supposed problem. After a few moments, one of the actors explained that they were having technical difficulties. Fortunately, they had candles, which would be perfect to light the next scene, in which Kohlhaas meets Martin Luther. The performers lit candles and proceeded to sing the next scene, changing the words to a traditional Lutheran hymn. At the end of the song, the lights miraculously came back on, with a ray of white light beaming down as if from heaven.

It was not this one clever gimmick that made the show, but rather the production’s ability to find a long string of clever gimmicks, each one more creative and surprising than the last. With each new scene came a new innovation, a new twist, whether it was petitions run through an on-stage paper shredder or shadow puppets enacting the burning of a city. Though the performers should have been exhausted after the physically demanding piece, they even rushed outside the Fringe tent afterward to greet the children in the audience and hawk commemorative clown-face buttons.

Not nearly as many young people were in the audience for Songs for Alice, a Fringe production put on by Germany’s Figurentheater Wilde und Vogel. The performance, in both English and German, included rather adult renditions of scenes from Lewis Carroll’s Alice books as well as most of the songs and poems that appear in the stories. A hoarsely sung version of “The Walrus and the Carpenter” provided structure for the piece, with the main puppeteer periodically breaking out into verses as the play transitioned between scenes. The performance both began and ended with the poem, concluding with a dramatic blackout when the song announced the betrayed oysters had been “eaten every one.”

Carroll’s Songs for Alice. Figurentheater Wilde und Vogel, Recklinghausen, 2013. Photo: Therese Stuber.

The puppets were quite impressive. They included one hand puppet of a face placed directly in front of the puppeteer’s own face while he was wearing an elaborate costume and headgear. The effect was to make the puppet look like a mask, but it could be manipulated in ways no mask can be moved. Also notable were a caterpillar puppet that blew smoke and a white rabbit puppet that was both comical and vaguely threatening at the same time (much like Carroll’s stories).

While many of the songs were performed in English, a notable exception was “Jabberwocky,” which was performed in German. This was an interesting choice, as much of the poem consists of made-up nonsense words anyway. Though it was surely a feat to translate “‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves” into German, this was probably the right decision for a predominately German-speaking audience. Nonsense always stands out the most when it is juxtaposed with something from one’s own mother tongue.

Though the performance (and the festival as a whole) had some slow moments, Songs for Alice (like the festival) contained so much creativity it ensured the audience was never bored. That’s enough to make one chortle in joy.

Carroll’s Songs for Alice. Figurentheater Wilde und Vogel, Recklinghausen, 2013. Photo: Therese Stuber.

is a graduate student in the PhD program in theatre at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. He has published theatre reviews in The Edgar Allan Poe Review and The Dickensian. His own plays have been published by Applause, Eldridge Plays and Musicals, and Original Works Publishing.