This article was scheduled to appear in Slavic and East European Performance (SEEP) in 2012. Due to the merger of SEEP with Western European Performance (WES) the publication was postponed. The significance of Michał Zadara’s performance of Awantura Warszawska for Polish contemporary theatre and performance warrants its publication at this time.

After 1990, that is, after the fall of communism in Poland, every anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising has been celebrated with memorable events involving special church services, meetings with veterans, concerts, and special performances. The Uprising that broke out on August 1st, 1944 and ended 63 days later, on October 2nd with the capitulation of the city—was the last heroic effort of the underground Polish Home Army to free Warsaw from Hitler’s occupation and to prevent the city from falling under the advancing Russian army. Underestimated and fairly unknown in the West, the Uprising still triggers a great deal of intense discussion among Poles of all generations. Some Western historians, such as Norman Davies and more recently Alexandra Richie, have contributed to documenting various aspects of the uprising as well. In the summer of 2011, on the 67th anniversary of the Uprising’s outbreak, the voice of Polish theatre director Michał Zadara joined these discussions adding a significant and forceful dimension.

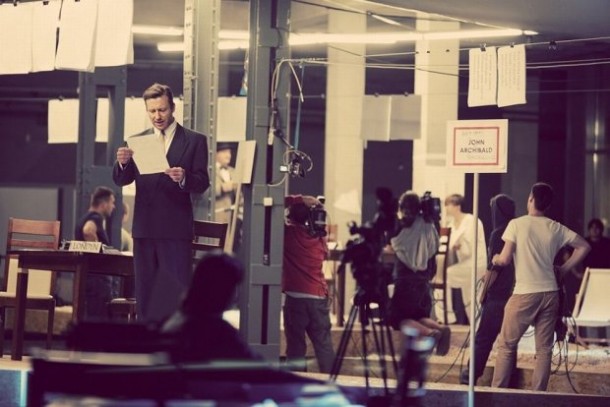

Zadara, an alumnus of the Swarthmore College Theatre Department, and a student of Alan Kucharski, created a breathtaking documentary performance at the Warsaw Uprising Museum. Separate platforms in the entrance hall were meant to show the offices of The Big Three: Winston Churchill, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Joseph Stalin, as well as the quarters of the Polish government in exile including president Edward Raczyński (Adam Szczyszczaj), prime minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk (Tomasz Cymerman) and other politicians whose decisions were fundamental to the Uprising’s outcome.

The site-specific piece took place under the wings of the B-24 Liberator, an American-British warplane, shot down during the attempt to drop food and ammunition for the fighters of Warsaw. The space under the Liberator added a special dimension to the performance since it alluded to the Allies meager and largely unsuccessful airdrop (most of the desperately needed ammunition and food fell into German hands). On slightly elevated platforms (about five or six of them placed in different places under the plane), the actors made the drama of the prelude, the actual fighting, and the eventual defeat of the Warsaw Uprising come alive, not only through dialogue among themselves, but also by reading and writing the diplomatic telegrams exchanged between the British, American, Russian, and Polish politicians. The main focus of this flurry of telegrams was the question concerning diplomatic and military support of the Western Powers for the fighting in Warsaw. The uninterrupted, steady, non-emotional day-by-day narrative mainly registering the numbers of deaths, read by the actress Barbara Wysocka, created an ominous background for the politicians’ hasty diplomatic exchanges. Equally foreboding was the projection above the performance space of the date of each day of the Uprising, providing a chilling countdown to its inevitable defeat.

The spectators were either positioned as bystanders—closely following the action on the platforms—or as more distant viewers. Those who chose the first option walked between the platforms where telegrams clipped to the wires above the actor’s heads continuously arrived. The spectators stood around the platforms watching clerks typing responses, politicians vigorously discussing their issues, and envoys running with the dispatches deciding the fate of thousands of hungry, desperate fighters on the streets of Warsaw. On one platform, Winston Churchill (Juliusz Crząstowski) smoked his cigar and conversed with Anthony Eden (Jacek Piątkowski); on the other, Franklin D. Roosevelt (Edward Linde-Lubaszenko) moved quietly in his wheelchair; yet another showed Joseph Stalin (Sean Palmer) grinding his teeth in the conversation with Vyacheslav Molotov (Grzegorz Młudzik). From yet another platform-island, the Polish government in exile (located in London) was sending desperate appeals to the Western allies for help. Actors’ foreheads dripped with sweat, the dispatchers were running and the politicians shouting out their questions and decisions. Everybody was nervous, agitated, and emotional. The whole performance was in constant motion with the main action foci indicated by the spotlights. Specific platforms were suddenly lit, voices raised, the typewriters began clicking, and the dispatches started arriving. Then the lights would die out and the action would move to another platform. So the viewers, at least at the beginning, practically ran with the actors from one focal point to the other.Thus they were pulled into the performance, embodying the disjointed, desperate, and sometimes pathetic reaction of the Warsaw inhabitants to the Uprising’s unfolding. As the fight moved into its second phase, when all the efforts of getting help from the West brought no results and the narrator informed us of her own death, the energy between the actors and the spectators changed: people’s faces became concentrated, motionless, and painfully grave.

The whole performance was simultaneously videoed and projected onto a large screen in the museum’s sunken amphitheater, adjacent to the space under the Liberator plane, an integral part of the performance space. Thus Zadara’s spectacle not only presented the Uprising’s story (with its reception and evaluation) but immediately commented on the very process of the construction of the historical narrative and the significance of the media in contemporary modes of historicity.

The filmed version created a very important angle for the audience to follow the unfolding events: apart from moving around the platforms, very close to the actors, the audience could sit in the amphitheater and watch the version projected on the screen. (They could also combine the two: walking around the platforms and then watching the screen). Because the amphitheater and the screen were sunken below floor level, a large space on three sides of the screen allowed a clear view, and those without seats were encouraged to stand around the edge and watch the screen. The live action as it was simultaneously projected onto the screen gave the spectators a chance to follow the events unfold through the camera lens. In contrast to the fragmented, hasty, haphazard “direct perceptions,” they could see another, more limited version, mitigated through multiple camera lenses. In a sense, the projected version simulated an actual newsreel of the time or a documentary registering the unfolding events. But Zadara’s performance makes it clear that the eye of the camera was one of the possible versions of the Uprising narrative. Through different camera angles and voiceovers, the sounds of the live action taking place behind the screen and the audience members moving about—on and off screen—the live, uncontrolled flow of events was transformed into an historical narrative. It has to be stressed though that the theatrical side of the performance left the viewers the freedom of choice and every single spectator could construct his or her own “version” of the unfolding spectacle.

If we decided to watch it on the screen, we could see a close-up of one actor reading a report with great urgency into a huge, old fashioned radio microphone with the camera capturing from below every fold of his flesh and pore in his skin. Even more powerful and telling was the scene towards the end of the performance when Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt push brooms across one of the platforms, sweeping huge piles of thousands of matchsticks revealing the map of Europe painted on the platform below. The camera was there to show the viewers the borders as they changed. The Big Three pushed and pulled the mounds of matchsticks, covering and uncovering parts of countries as they drew and re-drew the map of Europe before our eyes. Then the perspective shifted to the level of their feet, revealing these giants sweeping matchsticks off the edge of the platform, reminiscent of the heaps of emaciated bodies, mercilessly bulldozed into pits. The camera then looked up at the three self-satisfied leaders as they stepped back to admire their handiwork, a powerful image telling us, wordlessly, all we need to know about the closing days of World War II. This striking point of view was more prominently available on the screen, and it was indeed powerful. It also affected our intellectual reaction to this image. For the viewers watching this spectacle directly on the platform—the very physicality of pushing the brooms, and the steady rhythm and sound of the falling matches—enhanced the gravity of that scene and created a most captivating and gruesome experience.

The spectators could easily leave their view of the screen and join the performers and other viewers around the platforms. In that way they were encouraged to participate in as many or as few points of view as they wished, unlike the real historical actors who only had their very limited windows on the events taking place so far away. They were able to see so much more and thus appreciate the depth of the nature of the Warsaw Uprising. Still the spectators saw this through the reports, the typewritten pages, the radio broadcasts, the “newsreels” of the behind the scenes drama as it unfolded in Moscow, Warsaw, London, and Washington.

The “story” of the Uprising taking shape before the spectators showed how the derogatory term, “Awantura Warszawska” (Warsaw Brawl), invented by Stalin, was eventually adopted by Churchill and Roosevelt, and how Stalin dominated the discourse. Other viewpoints were marginalized and an agreement reached: this extraordinary event would be called “a brawl”– nothing more. Stalin imposed his wording to the “democracies” and with barely a whimper those democratic leaders fell into line. The tumult and bustle of the platforms began to die down, the chaos was given a name, a form, the condescending, almost frivolous name “brawl.” The platforms started to grow silent and dark, save for the Polish Government in exile where Premier Stanisław Mikołajczyk, Ambassador Edward Raczyński and others shout themselves hoarse.

The strands were pulled together, the media outposts, once so dynamic, so full of the drama of the remarkable news that one of the conquered peoples rose up against their oppressors, but that in the end, the Uprising was hammered down at least in part with the acquiescence of the Big Powers. The audience saw it rise, reach a crescendo of words and papers, and then die back down, the threat averted; the script as written by the Big Three came to dominate.

Combining the direct, live performance with the filmed version created yet another meta-perspective about the very process of history making. How do we document and register the emotions accompanying an historical event? How do we remember our insecurities, fear, ambiguities, and other emotions we cannot even name that so often accompany strenuous historical circumstances? Is it possible to ever share these feelings and emotions? Zadara’s docudrama shows that it is possible. It documents the historical events, localities, people and their actual actions and statements asking important questions about their historical validity. But perhaps even more importantly, it recreates the emotions. The direct action at the platforms agitates the spectators’ physical experience; they move with the actors, almost touch them, feel their bodies, and thus become aware of their own physical frame. When the spectators run from one platform to the other they feel other people bumping into them and experience their bodies’ fragility and their own insecurity. This is how the performance’s physicality helps recover the intergenerational memory. At the same time the projected version, while presenting an overall narrative (mediated by the camera), allows for a more distanced intellectual perception of events.

The performance abounded in simple yet extremely rich and powerful theatrical ideas; every situation and gesture triggered layers of associations and meanings. For instance, every telegram read aloud by a specific politician from the A4 sheets that we first saw hanging above the platforms was then discarded on the floor. So that towards the end the people walked over the piles of critically important pieces of history and diplomatic exchanges that were no longer valid or useful. We could literally trod over hundreds of peoples’ lives lost in the battle. The scene in which Edward Linde-Lubaszenko, playing Roosevelt, makes paper airplanes out of the letters covering his desk and throws them in the air against the spectators amplified this image of history’s volatility.

Integrating actors and audience, archival historical materials, personal narratives, memory, live action, and cinematic projection within a specific, historically marked space all contribute to the uniqueness of Zadara’s spectacle. In Awantura Warszawska, the director explores theatre’s potential to the utmost, enhancing the historical experience through theatricality, so that we really live it. The actors’ and the audience’s participation fills the documentary material with real emotion and makes the historical event deeply experiential. As much as history is made alive through the multifocal and multilayered performance, the performance itself is enriched by the plethora of the presented material so that one enriches the other. Zadara shows how no other art but theatre can contribute to such a full participation in a historical experience. This is why a performance created four years ago remains such a signpost on the map of documentary theatre.

Awantura Warszawska was performed at The Warsaw Uprising Museum, August 2011. Direction: Michał Zadara, stage design: Robert Rumas, costumes: Julia Kornacka, dramaturgy: Daniel Przastek. Cast: Krzysztof Boczkowski, Arkadiusz Brykalski, Juliusz Chrząstowski, Tomasz Cymerman, Szymon Czacki, Edward Linde-Lubaszenko, Sean Palmer, Jacek Piątkowski, Grzegorz Młudzik, Adam Szczyszczaj, Barbara Wysocka.

teaches Polish language, theatre, and film at Yale University. She writes on Polish-American cultural exchanges, theatre, and film. She has published both in English and Polish about Witold Gombrowicz, Bruno Schulz, Tadeusz Kantor, and others. Currently she is working on a book tentatively titled The Image of America in Poland in the 1920s and 1930s.

teaches writing at New York University and has published on Chinese philosophy. His photographs have been featured in Kwartalnik Artystyczny (Poland). His interest in Polish theatre and its relation to the post-communist public sphere stems from his study of early 20th century China.

European Stages, vol. 4, no. 1 (Spring 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Report from Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- Performing Protest/Protesting Performance: Golgota Picnic in Warsaw by Chris Rzonca

- A Mad World My Masters at the Barbican by Marvin Carlson

- Grief, Family, Politics, but no Passion: Ivo van Hove’s Antigone by Erik Abbott

- Not Not I: Undoing Representation with Dead Centre’s Lippy by Daniel Sack

- In the Name of Our Peasants: History and Identity in Ukrainian and Polish Contemporary Theatre by Oksana Dudko

- Performances at a Symposium: “Theatre as a Laboratory for Community Interaction” at Odin Teatret, Holstebro, Denmark, May, 2014 by Seth Baumrin

- Songs of Lear by the Polish Song of the Goat Theatre by Lauren Dubowski

- Silence, Shakespeare and the Art of Taking Sides, Report from Barcelona by Maria M. Delgado

- Little Theatres and Small Casts: Madrid Stage in October 2014 by Phyllis Zatlin

- Gobrowicz’s and Ronconi’s Pornography without Scandal by Daniele Vianello

- Majster a Margaréta in Teatro Tatro, Slovakia by Miroslav Ballay

- Remnants of the Welfare State: A Community of Humans and Other Animals on the Main Stage of the Finnish National Theatre by Outi Lahtinen

- Mnouchkine’s Macbeth at the Cartoucherie by Marvin Carlson

- Awantura Warszawska and History in the Making: Michał Zadara’s Docudrama, Warsaw Uprising Museum, August, 2011 by Krystyna Illakowicz and Chris Rzonca

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016