When the actor and director Josep Maria Pou informed me that he was staging Ronald Harwood’s Taking Sides, first produced in 1995, at Barcelona’s Teatre Goya, I was a little surprised. My last encounter with the piece, István Szabó’s 2001 film adaptation, left me thinking this was a rather dated morality play. But watching the piece again in Pou’s clean, crisp production, presented as Prendre Partit in a Catalan translation by Ernest Riera, the staging resonated as a defiant indictment of the systematic politicization of culture in Spain. Harwood’s play contrives a courtroom-like encounter between a coarse, combative American military officer, Major Steve Arnold (Andrés Herrera), who confronts the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler (Josep Maria Pou), over the latter’s supposed collaboration with the Nazis during the Third Reich. The altercation takes place in the Berlin headquarters where Arnold is stationed with his Jewish lieutenant, David Wills (Sergi Torrecilla) and secretary Emmi Straube (Anna Alarcón). In Joan Sabaté’s grey imposing set, this is a post-war world of muted walls, broken windows and high arches, where people are dwarfed by their surroundings: tiny cogs in a bleak, existential machine, where agency too often seems a thing of the past.

Arnold, a former insurance claims investigator, is first seen asleep in a chair. But the rousing sounds of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in C Minor soon spur him into action. He jumps up like a clockwork toy, overly excited at the prospect of nailing the eminent German conductor for his supposed collaboration with the regime. Herrera’s Arnold is dogged in his pursuit of these “degenerates.” He clutches files in search of incriminating evidence, wags his finger and points in an accusatory manner. He is a man with a mission and won’t, as he nonchalantly informs his Lieutenant, let facts get in the way of “nailing the bastards.”

Pou’s production shows Herrera’s stocky Arnold to be as inflexible as those he denounces, and his cropped hair and small moustache cannot help but posit an analogy with Hitler. He snarls and bites, issuing orders like a brusque snapping dog. He darts and jives like a boxer hoping to pull a punch on his opponent. On the other side of the ring, Pou’s lugubrious, aging Furtwängler bides his time. A meticulous man, economical in his moves, Furtwängler is watchful of whom and what is around him. On his first appearance, he removes his gloves in a cautious manner as if carefully peeling off a layer of skin. Furtwängler’s stillness is consistently contrasted with Arnold’s pent-up rage. Furtwängler knows that there are no absolutes, nothing that is fixed or determined. Music is the art of interpretation, and Emmi and David admire Furtwängler’s epic, weighty renditions of Beethoven’s scores. His recordings sweep them away into a space where they are transported into a place of beauty where subjectivity is played out.

Arnold cannot accept a grey position, insistent that Furtwängler’s decision to remain in Berlin during the War as conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra confirms his commitment to the ideology of the regime. He is triumphant in tone when crowing that Furtwängler sent Hitler a telegraph on his birthday and gleefully waves a file of papers revealing the conductor’s extra-marital affairs. The socially awkward Helmuth Rode (Pepo Blasco), a former second violinist with the orchestra, testifies to the conductor’s courage in refusing to give Hitler the Nazi salute, but the increasingly agitated Arnold refuses to listen. There is no room for ambiguity in Arnold’s world.

And yet Pou’s production consistently refuses to take sides. The restless, animated Helmuth Rode was able to obtain a position in the Berlin Philharmonic because Jewish musicians were excluded from the orchestra. The privileged Furtwängler may have been on the Nazi’s Gottbegnadeten (Important Artist list) but he used his position to help Jewish musicians to leave Germany. Arnold irritates and abuses; he refuses to see the poetry and energy in Furtwängler’s recordings, referring to the conductor as “Hitler’s bandleader,” but he also acknowledges the weight of the dead that hangs over the grey, fractured landscape in which the characters operate. The distraught widow of a pianist exterminated in a death camp defends the conductor’s attempts to get her husband out of the country. “You want to burn him at the stake,” she tells Arnold. He has indeed internalized the culture of polarized, binary opposites that so defined Nazism.

The two desks in the large bombed building look like tiny satellites in a murky void. Furtwängler is positioned center stage as a point of gravity around which the restless Arnold hovers. Pou’s Furtwängler stoops but holds his ground: the shuffling is minimal, the responses measured. “I love my country. I believe in art. What could I do?” he states. In his own defense, Furtwängler claims he gave spiritual nourishment to the German population during trying times. Collaboration is shown to take many shapes and forms: Helmuth’s involvement asks a series of questions about what the general populace knew or didn’t know and how they colluded in the operation of the regime, benefitting from the misfortune of the persecuted Jews. Herrera’s Arnold, an image of imperialist arrogance, marches around Furtwängler like a dog with a bone, like Death dancing in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, only he is alone without the travelers following on. David and Emmi refuse to go along with him, choosing to occupy a less partisan position. They stand still listening to the sweeping lyricism of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, which Emmi puts on the record player as the Major screams out of the horrors of the gas chambers.

The parallels with contemporary Spain are not difficult to spot. Spain has its own contested history of collusion with a dictatorship responsible for overthrowing a democratically elected government. A series of artists went into exile at the end of the Civil War rather than collaborate with Franco’s regime. Furthermore, in contemporary Spain, as politicians meddle in cultural appointments and effectively censor culture through legislation that seeks to marginalize the artistic, Pou’s production argues for a more considered contemplation of artistic worth and ethical responsibility. The production’s run coincided with the Goya (the Spanish equivalent of the Oscars) award’s ceremony, where Pedro Almodóvar stated that José Ignacio Wert, Spain’s Secretary of State for Education, Culture and Sport is not included as a friend of culture and Spanish cinema. When political opportunism dominates, culture functions as a pawn and commodity. The overwrought Arnold may have legitimate concerns, but his refusal to listen to the terms of engagement of his opponent displays an absolutism that undermines democracy’s ability to operate in the grey areas that exist between the black and white extremes of dictatorships.

Jordi Bosch plays the bank manager and Jordi Boixaderas the client in Jordi Galceran’s entertaining The Credit (El crèdit) at the Villaroel Theatre. Bosch’s role is now taken by Pere Ponce. Photo credit: David Ruano

Jordi Galceran scored a veritable hit with his earlier El método Grönholm (The Grönholm Method), a desperate tale of neo-liberalism’s excesses refracted through the shenanigans experienced by a trio of applicants attending a job interview for a shady multinational corporation. El crèdit (The Credit) occupies similar terrain; only the heady mood of the good years where jobs were more plentiful has been replaced by a more discerning plea for assistance. Jordi Boixaderas plays Antonio Vicente, a client who has come to see Pere Ponce’s smug bank manager in the hope of securing what appears to be a much-needed loan. (Ponce replaces Jordi Bosch in the role in the production’s extended run). We never find out why he is in this predicament but the situation needs no explanation in the climate of contemporary Spain. Vicente is one of the 24% who have now fallen on hard times in a country where 5.6 million are unemployed. Ponce’s bank manager is not prepared to be lenient. Vicente is not presenting a persuasive enough case, until suddenly he pulls out an Ace card: “Give me the credit that you’re refusing me or I’ll seduce your wife,” he states. As Ponce looks on with incredulity, Vicente delivers the killer shot: “You’ll then have to manage with 30% of your salary and go off to rent a place in Parla.” The bank manager stops in his tracks. “How do you know that this is happening to my brother?” It seems that his brother’s predicament—marital separation and less than ideal living conditions away from the family home—have struck a raw nerve with the complacent bank manager. There’s a chink in the armor, and Vicente now begins to exploit it.

The action evolves in a circular pod-like structure designed by Max Glaenzel. The roof lifts on this spaceship-like space as the play begins. The percussive sound of ringing phones goes into overload as Ponce’s gruff bank-manager prepares to deliver his verdict on the credit request. The set revolves slowly like a merry-go-round, taking us along on the ride with the two protagonists. It is a situation (perhaps like that of contemporary Spain), which is soon shown to be spinning somewhat out of control.

This is a tightly plotted, well-made play of entertaining extremes. It works through broad brushstrokes rather than subtle interventions. Act 1 has Vicente trying to make the case for the loan, while the bank manager holds firm. Meanwhile the revolve moves below them, sending both men on a rollercoaster journey. The bank manager’s desk boasts an airbrushed family photograph—a glamorous wife and two smiling children—who look out at the down-on-his-luck Vicente. The bank manager wears a pink shirt and a sharp grey suit; the client has a baby blue shirt and beige trousers. The pastel colors point to infantilization, to two men in contrasting positions who don’t appear to want to find a meeting point. When Vicente throws a spanner in the works by threatening to sleep with his wife, something becomes unhinged in the tightly wound bureaucrat. As the bank manager becomes more animated, the client embraces stillness. The bank manager tries to get him to leave, but Vicente remains determined to stay; he’s not finished trying to secure the desired loan.

The timing of both actors is exquisite, like a perfectly pitched game of table tennis, and it builds up to the crescendo when Boixaderas’s client purses his lips, looks slightly disappointed but then flounces off, issuing a warning to the ever more uptight bank manager that his wife remains a target. When the client departs, the bank manager breathes a sigh of relief. A telephone call with his wife, Laura, however, sows the seed of discontent; she sees things differently. The client only wanted to borrow 3,000 euros she tells him, and her husband evidently didn’t think she was worth that level of meagre investment.

Act 2 witnesses how the seeds of discontent have festered and taken root. The bank manager and his wife have separated. The former’s perfectly pressed suit of Act 1 is now crumpled, and he is waiting eagerly for the client. The tables have been turned. The bank manager is now fawning with excessive politeness, while his fevered, caffeine-drenched eyes tell a story of hysteria and over stimulation. Discarded coffee cups litter his once immaculate table. He can’t sleep and looks out of sorts. The bank manager wants his old life back and is recklessly throwing credit at Vicente—12,000 euros instead of the 3,000 he initially requested: another reference to the irresponsible spending that brought Spain to its knees.

We soon learn the reason for the bank manager’s distress. Vicente’s threat has come to pass, at least in part: his wife, Laura, has thrown out Ponce. He’s now trying to show her that he’s a changed man and has enlisted the client to aid him in this endeavor. Vicente finds himself giving tips to the bank manager on wooing his wife: look her in the eyes, don’t look at her tits, be sincere and say her name. Jordi Boixaderas’ is very funny indeed enacting the courting tips of the client who knows he’s onto a good thing. Like a faith healer, he grabs Ponce’s hands and pretends to be the bank manager seducing his wife anew. The bank manager can no longer even remember what makes his wife special for him. He wants her back but as another object in his life. Vicente is not allowed to leave until Laura allows him back home. Neo-liberalism’s values are shown to contaminate all aspects of domestic life.

Galceran is too slick a writer to let the client sleep with Laura—that would be too easy a trick. They speak by phone, and get on famously well, but it is the revelation that Laura is actually sleeping with her brother-in-law that serves as the final farcical twist. As a new credit loan is negotiated between the two men, the lid of the pod comes down and seals the two performers back in their box. The toy merry-go-round has wound down; the two animated toys have been put to sleep, but the nation remains in a spiral of debt and borrowing that shows no sign of abating.

El crèdit proffers a variation on the odd-couple pairing; two contrasting characters forced to co-exist in a restrictive space where they run and tumble like mice in a cage. Sergi Belbel directs the action with impeccable timing. Boixaderas and Ponce dart and dance. Boixaderas is slim and scheming, Ponce slightly bulkier and greyer. As the set girates, the men move around in a scheming waltz of undeclared intentions. Ponce’s legs kick up like John Cleese’s Basil Fawlty. Boixaderas slips around him opportunistically. El crèdit offers 80 minutes of high-energy jinks packaged as a contemporary farce of deceptions, misunderstandings, situational humor, and improbabilities. Don’t delve too deeply; don’t look at plausibility; just admire the virtuoso energy and allow yourself to be carried away by this tale of two alpha men negotiating a crisis of masculinity in a climate of collapsing capitalism.

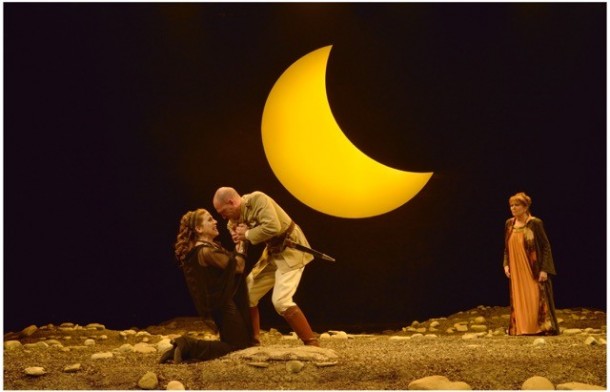

Phèdre (Emma Vilarasau) and Hippolytus (Xavier Ripoll) locked in combat while Mercè Sampietro (Oenone) looks on in Sergi Belbel’s Phèdre (Fedra) at the Teatre Romea. Photo credit: David Ruano

When I first saw the set for Sergi Belbel’s Phèdre at the Romea theatre, I thought he might be revisiting the environment he deployed so effectively in his 2014 production of Beckett’s Happy Days. This was a rocky wasteland, an abandoned quarry that told of uncompleted projects and washed out lives. Winnie and Willie were trapped within a mound of rubble that evoked the abandoned construction sites and half-built or empty abodes scattered across Spain. The landscape for Phèdre is similarly rocky, boasting a small rock pool where the characters of Racine’s tragedy find some relief from their illicit desires and suffocating sense of guilt. They roll, fall and tumble into its waters for some release when things get overly heated. This is tricky terrain to negotiate both physically—the actors never seem entirely at ease on the set—and linguistically—Racine’s verse needs inflections and nuances that disturb what can too easily fall into histrionics and inflated rhetoric.

This is a production that never quite finds its register. Xavier Ripoll’s clean-shaven bare-chested Hippolytus first bounces on stage as an image of unbridled sexuality. The tone is too declamatory, too intense. He looks like a man in a hurry but we never quite sense where he is going. Similarly, Emma Vilarasau’s Phèdre appears too distraught, flapping her arms and swaying in a trance-like horror. Clad in a Demis Roussos-like tunic and treacherous gladiator-sandals that she never quite looks comfortable in, she presents an uneasy portrait of transgressive desire. There are moments when Vilarasau resembles Rosa Marià Sardà—arched eyebrows and pursed mouth. She tries to contain herself, clutching her body in desperation, but somehow her gestures all appear suspended in a register where nothing quite comes together to create a unified stage world.

Mercè Sampietro has more success as the more pragmatic co-conspirator, Oenone. Her calculating wiliness offers a welcome contrast to the flaying arms and histrionics of Vilarasau’s Phèdre. She is also the one actor who is able to grip and occupy the Alexandrine verse (here presented in Belbel’s own translation). Queralt Casasayas offers a welcome serenity as the lovesick Aricia. Her tranquility is a potent allure to the lovesick Hippolytus; she floats across the stage like an angel untarnished by the chaos that engulfs Phèdre, Hippolytus and Theseus. Lluís Soler is an overly wooden Theseus, furs draped over his military uniform, with no real shifts in register to suggest the emotional tumult he is experiencing. Glaenzel’s design provides a solar eclipse that watches over the action. Its steady progress into a lunar moon is a telling omen of the inevitability of the tragedy and a dramatic backdrop to the action. The rolling drums and scratchy music that underscore the dialogue further accentuate the heavy-handed atmospherics deployed by Belbel. Phèdre and Oenone’s entries and exits through the theatre’s central aisle don’t quite manage to involve the audience in the ensuing tragedy. Rather they rupture any sense of build-up, dismembering the action in the process. Hippolytus’s battered, bloodstained body, displayed onstage in the final scene, feels excessive. The end result is a patchy staging where the histrionic aesthetic—culminating in Phèdre’s death, stumbling poisoned across the stage like a zombie before falling into the water—suffocates the subtleties of Racine’s tragedy.

Lear’s (Núria Espert’s) ceremonial entry to divide the kingdom in Lluís Pasqual’s King Lear (El Rei Lear) at the Teatre Lliure. Photo credit: Ros Ribas

Subtleties are at the fore of the Teatre Lliure’s King Lear, presented in Joan Sellent’s clean, clear translation, which director Lluís Pasqual has adapted further. The production has proved to be the sell-out success of the season, bringing together a stellar cast with 79-year old Núria Espert, the grande tragedienne of Spanish theatre, taking the title role of the 80-year old Lear. It’s a production that slots perfectly into a Lluire season where artistic director Pasqual asks pertinent questions about the cultural space the theatre occupies and what it should be doing in these compromised times.

The staging is traverse: an empty long wooden-floored corridor with platforms that rise and fall to create the different spaces of the play: tables, cliffs, stairways, stocks. At each end, there is a terrace where an organ and drums provide percussive accompaniment to the action. The playing space is almost like the central aisle of a cathedral, where the audience who has gathered there for the ceremonials observes the comings and goings. The implication is that alongside the play’s assembled characters—who sit in cinema-style seats that form the front row of the audience—we too have to hear Lear’s big announcement. The characters sit and observe the proceedings when not taking part in the unfolding tragedy. Even Lear is shown to be part of this process. Pasqual’s production implicates all in the making of this tragedy. Up above the audience two screens project images that comment on the progressing narrative—an eclipse for Edmund’s monologue, stormy skies and lightning for the storm scene, the cliffs of Dover where Mad Tom leads Gloucester. This is a production that is not afraid to negotiate the horizontal line of the narrative with the vertical scope of the spheres, the metaphysical and the spiritual. We are encouraged to look across the horizon at the comings and goings of the characters and gaze up at the screens as the characters talk of gods, spheres, tempests, storms, and the heavens. Both lines intersect to potent effect in Pasqual’s retelling of the story.

In the opening scene, the court prepares for the King’s announcement. Jordi Bosch’s exacting Gloucester is at the ready, weighed down by a long heavy wooden coat and a sense of occasion. He chats to Ramon Madaula’s Kent—a distinguished, good looking military officer, in contrast to his habitual representation as the grey man of the court. Here it is David Selvas’s Edmund who fades into the background, a figure whose charcoal grey combat trousers and shirt suggest that he would like to be part of the military grouping at court. The keen pacing and bustling provides momentum and heightened anticipation. Lear’s entry is marked with pomp and ceremony, the King’s arrival heralded by a dramatic procession of courtiers carrying burning torches. The crown may be modest but the ego is large. Espert’s Lear is a fickle, wily monarch, used to getting her own way. There is something of the petulant child here. She enters with her hair tied back and head held up high, like the cat that has the cream. She looks at her court knowing what she expects of them, and when those she holds most dear do not deliver, she unleashes her quick tongue and angry temper: her wrath is merciless.

For the division of the kingdom, Miriam Iscla’s Goneril and Laura Conejero’s Regan face Lear across the other side of the stage. The width suggests a schism that Lear cannot recognize. The two elder daughters look as if they’ve dressed up for the event. Goneril sports a long, dark green dress with a fixed broad grin as broad as a Cheshire cat. Regan is in brown, in a toned-down version of her sister’s dress. These sisters occupy the same emotional terrain. Even their bearded and identically clad husbands look as if they might be cloned. They have come to play a role of devoted daughters before a parent keen to receive the rhetoric of worship, reverence, and adulation. And in the moment in which Lear confuses these empty platitudes for love and affection, the tragedy is set in motion.

Kent (Ramon Madaula), Lear (Núria Espert) and Cordelia (Andrea Ros) in Lluís Pasqual’s King Lear (El Rei Lear) at the Teatre Lliure. Photo credit: Ros Ribas

Andrea Ros’s Cordelia, on the other hand, is a very different entity. Much younger than her two sisters, she is a Jean Seberg-like figure with a short, cropped hairstyle, black Capri pants and a matching top. She looks like she’d be more at home in existentialist 1950s Paris than at this formal Court. This tomboyish sister is of a different generation—did the absent and never mentioned Queen die in childbirth? Cordelia’s physical distance from her sisters points to a dissimilar perspective on life. Her difference is defiantly marked out from her very first appearance.

Espert plays a monarch who likes the pomp and ceremony of her position. Her steely eyes look out sternly, her jaw hardening when Cordelia refuses to follow her sisters’ platitudes. She points an accusatory finger at Kent like a disapproving parent. On arriving at Goneril’s home, her soldiers fire a deafening salute to announce her entry. She swaggers like a retired general with a black beret, uniform, and grey coat. She is self-obsessed and insistent. A surly look, for an instance, recalls King Juan Carlos on the eve of his abdication—indeed, El País‘s Jacinto Antón noted in his review that there was an air of Spain’s ex King returning from one of his beloved hunts in Espert’s entry with her rowdy entourage (8 January 2015). There is also something, however, in her wrinkled frail hands and her shrunken frame swamped by the attire of military protocol that tells a tale of increased infirmity. Her face visibly crumbles as she leaves Goneril and Albany for Regan’s castle. Later when facing both Regan and her sister, she stretches out her arms in a gesture of extreme anxiety, appealing to both daughters to be permitted to keep her retinue. She grabs her Fool desperately during the storm scene and cuts an increasingly spectral figure as she exits in childlike high excitement with Poor Tom. As the production progresses, she is presented as an ever more wizened figure, but one attracted still to the trappings of her position. It is with a large paper crown and torn mustard skirt that she comforts the blinded weeping Gloucester who kneels at her feet in Act IV, Scene 6. Her undulating voice testifies to the broken down mind that tries to make sense of her elder daughters’ vicious behavior. She scatters confetti and paper flowers like a Miss Haversham figure—the gesture recalling one of Espert’s most celebrated roles as the abandoned spinster in Lorca’s Doña Rosita.

In Act V she appears in a wheelchair, a huddled, infirm figure struggling to put words together in a sentence. Her slippers and matching baggy cardigan speak of a senile geriatric wheeled out to greet visitors in a nursing home. She rises up stretching her neck like a giraffe to address her assembled friends as Cordelia attempts to keep her sane, kneeling at her feet as Lear acknowledges she is “a very foolish fond old man/Fourscore and upward.” She is too frail to carry the dead Cordelia in the play’s final scene—a practical reminder of what it means to have an actor of the character’s age take the role. The corpse weighs her down, and she can only lay prostrate beside it in grief and horror as she laments “Howl, howl, howl! O you are men of stones.”

Pasqual has stated that he cast Espert as she was the best actor for the role (El País, 8 January 2015), and the production makes no attempt to see Lear’s journey as gendered. Espert’s monarch, I would argue—with only a prosthetic nose to harden her features—moves between the male and female, occupying an in-between space where the play oscillates between the bleak and the empathetic. When Lear meets Gloucester on the heath, the latter kneels before him, just as Cordelia does in the play’s final act. These comforting moments offer a space for the male and female to co-exist through gestures of compassionate understanding. This is a tale of two fathers, and Bosch’s bulky frame presents a contrast to Espert’s frailer physique. The uniform may signal the masculine, but the frailer physique, the distinctive facial features, oval eyes, and distinctive shoulder-length cut serves as a reminder that this is Núria Espert. This purposeful androgyny ensures that the gap between monarch and wo(man) was perhaps less pronounced than in any other production I have seen. With Espert’s Lear the majesty is embodied additionally in an off-stage identity marked by a career that has lasted over 60 years. The diminutive physique—Espert was one of the smaller actors on stage—reminded the audience constantly of the infirmity and vulnerability of an individual in the latter decades of his/her life. It is a nuanced characterization that has at its heart an understanding of the horrors of an arrogance that lost all sense of perspective when it most needed it.

Pasqual’s staging demonstrates an understanding of the play as an ensemble piece. Lear’s foibles are underscored by Teresa Lozano’s Fool, an elderly companion in teetering heels, pink spotty trousers and a sky blue jacket that wouldn’t look out of place on a parading bullfighter. Her tufts of grey hair protrude clown-like from a dodgy headpiece. Her riddles to Lear are delivered as an abrasive Brechtian number and a sassy rap ballad, accompanied by Juan de la Rubia’s Weill-like accompaniment on the accordion-like sounds of the organ. She has an answer for everything and scampers about the space, following her master with dogged devotion and an energy that belies her years. During the storm she has a plastic bag on her head to protect her from the elements. She comforts Lear, allowing Espert to rest her head in her lap. With her bright makeup and rosy cheeks, and rucksack perched perkily on her back, she looks like a figure that might have sprung from Alice in Wonderland. Hers is a Beckettian characterization—pathetic, absurd, and profoundly moving. There is something of the Vladimir and Estragon in her relationship with Kent, also. The attractive lieutenant puts his good looks to one side as he disguises himself as a hobo to serve his master in distress. Ramon Madaula’s Kent is quick and alert, pulling a knife on Oswald with deft dexterity and a generous shielding of Lear and the Fool from the storm in their time of need.

Míriam Iscla gives us a Goneril who is a chip off the old block, as firm and inflexible as her father. Indeed, when she mentions her father’s ‘unruly waywardness’ she might well be talking of herself and Oswald. She kisses Cordelia when the latter is thrown out by Lear, perhaps acknowledging that she too has a soft spot for the monarch’s favorite child; it may even be a fond farewell to her rival. Only when Edmund is mortally wounded by Edgar does her façade fall apart. Conejero’s Regan is a far more outwardly unstable being. Her hysterical high-pitched laughter echoes through the cathedral-like space as she wields a knife following the blinding of Gloucester. There’s a terrifying frenzy here that points to an alarming loss of self-control. The graphic horror of Gloucester’s blinding may well be a reference to Abu Ghraib, or indeed ISIS—I saw the production in a week where the extremist jihadi organization burned a Jordanian pilot alive in a cage, and the sadistic horrors of the play seemed all too contemporary. Regan and Cornwell suggest a regime out of control, with the former running off when her husband is injured like an out-of-control drone. Óscar Rabadan’s Cornwall is as unhinged as his spouse. He excitedly pierces out Gloucester’s eyes with his fingers, licking his fingers with glee. When he kisses Edmund passionately on the lips, we are not sure as to whether it’s a provocation or a signal of his desire for the wayward bastard brother. Evidently Edmund’s allure reaches beyond the two sisters.

Selvas’s Edmund isn’t averse to histrionics. He puts his arms out when making his case to his father in the play’s second scene, as if feigning crucifixion. He’s alert, smarmy and confident, and addresses the audience calmly and directly. This man can shift his demeanor to suit the season. In his coordinated attire, he presents a more assured figure than his less alert brother Edgar (Julio Manrique), whose burgundy jumper and coat have something of the languid student. As Poor Tom, Manrique slaps himself across the face and flagellates himself with the rope that holds up his rags. Gloucester looks at Poor Tom and there’s a moment when it is as if he isn’t sure if he recognizes something in the voice. But this is a play where parents find it hard to see what is immediately in front of them. And it is with the feverish Lear that Poor Tom finds a kindred spirit. Espert’s Lear is like an excited, curious child as she keenly asks Poor Tom “What hast thou been?”

The chorus of soldiers double as a band accompanying the Fool’s songs. They chant as Edmund and Edgar do battle to provide a sense of heightened anticipation and underline the ceremonial qualities of the production. Dani Espasa’s polyphonic score provides a link with Renaissance culture. Pasqual’s staging is deft and lithe. The motorized platform rises up to provide a table where Gloucester is pinned, tied, and blinded, as if he were a piece of meat for the slaughter. It moves to create the different levels of the treacherous heath for the storm. It opens to become the stocks where Kent is trapped. The actors sit in the audience watching the action. When Edgar takes Goneril’s letter from the dead Oswald, it is Miriam Iscla, sitting in the front row, who reads it out. The corpses of the two dead sisters are brought on stage for the play’s final scene. Regan’s face is respectfully covered by Kent, Goneril’s by Albany. In the face of these horrors, protocol must be respected.

It may be hard to believe, but there was no Catalan-language King Lear until 2004; now there is a second to match Calixto Bieito’s abrasive staging a decade earlier. In both productions, institutional ill-treatment is matched by domestic abuse, and the painful consequences of dementia and amnesia are made manifest for a twenty-first century Spanish audience coming to terms with the consequences of a culture of silence that has refused to speak of the abuses and corruption of either the dictatorship or the nascent democracy of post-Franco Spain.

King Lear returns to the Teatre Lliure from 17 December 2015 to 31 January 2016.

is Professor of Theatre & Screen Arts at Queen Mary University of London and co-editor of Contemporary Theatre Review. Her books include “Other” Spanish Theatres: Erasure and Inscription on the Twentieth Century Spanish Stage (MUP, 2003) and Federico García Lorca (Routledge, 2008), the co-edited Contemporary European Theatre Directors (Routledge, 2010), three further co-edited volumes for Manchester University Press, and two collections of translations for Methuen. Her co-edited volume, A History of Theatre in Spain, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2012.

European Stages, vol. 4, no. 1 (Spring 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Report from Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- Performing Protest/Protesting Performance: Golgota Picnic in Warsaw by Chris Rzonca

- A Mad World My Masters at the Barbican by Marvin Carlson

- Grief, Family, Politics, but no Passion: Ivo van Hove’s Antigone by Erik Abbott

- Not Not I: Undoing Representation with Dead Centre’s Lippy by Daniel Sack

- In the Name of Our Peasants: History and Identity in Ukrainian and Polish Contemporary Theatre by Oksana Dudko

- Performances at a Symposium: “Theatre as a Laboratory for Community Interaction” at Odin Teatret, Holstebro, Denmark, May, 2014 by Seth Baumrin

- Songs of Lear by the Polish Song of the Goat Theatre by Lauren Dubowski

- Silence, Shakespeare and the Art of Taking Sides, Report from Barcelona by Maria M. Delgado

- Little Theatres and Small Casts: Madrid Stage in October 2014 by Phyllis Zatlin

- Gobrowicz’s and Ronconi’s Pornography without Scandal by Daniele Vianello

- Majster a Margaréta in Teatro Tatro, Slovakia by Miroslav Ballay

- Remnants of the Welfare State: A Community of Humans and Other Animals on the Main Stage of the Finnish National Theatre by Outi Lahtinen

- Mnouchkine’s Macbeth at the Cartoucherie by Marvin Carlson

- Awantura Warszawska and History in the Making: Michał Zadara’s Docudrama, Warsaw Uprising Museum, August, 2011 by Krystyna Illakowicz and Chris Rzonca

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016