The Avignon Festival has a new director and a new direction. Forty-nine year-old Olivier Py, former director of the Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe, playwright, poet, director and novelist, is determined to build a younger, more varied audience in terms of age, culture, social and geographic backgrounds. He is not only committed to a younger audience but also to younger playwrights and directors. He intends to showcase their work along with more familiar artists; only twenty to thirty percent of festival shows are by well-known names. This year he succeeded in lowering the cost of some tickets by means of a subscription (four shows for forty Euros) aimed at students and young people under twenty-six. There were also reduced priced tickets for adults who were attending more than five shows. While there have been presentations on the outskirts of Avignon for some time now, Py has been working to “decentralize” the festival even further and year round, especially in the working-class districts outside of Avignon. He has already been using the FabricA theatre in Monclar (a large modular space built under the previous directors and inaugurated during the 2013 festival) for rehearsals as well as festival productions (his play Orlando ou l’Impatience was rehearsed and presented in this venue this year).

Py frequently refers to his admiration for the ideas and accomplishments of Jean Vilar, the founder of the Avignon Festival in 1947, whose objective was to bring the ideals of his people’s theatre to Avignon. Even the festival logo – three keys – came from Vilar’s graphics. Py, too wants his festival to be a democratic festival that appeals to all individuals who are interested in the life of the mind. “My ambition is popular theatre.” (Le Monde, September 19, 2013) but he is well aware that theatre is not everybody’s cup of tea.

These are certainly generous and necessary goals if the festival is to attract a new audience, the audience of tomorrow, to borrow Py’s words. For awhile, however, it seemed that Avignon 2014 would not have any audiences at all, at least it was much rumored that France’s part time or seasonal cultural workers might close the festival down. These “intermittents,” as they are called, enjoy a special status in France, the “exception culturelle,” which gives them higher compensation, better benefits and social protection than the average unemployed person. They had been protesting a plan by the government to reduce their benefits and streamline their status since March, and throughout the spring they had already succeeded in stopping shows in Paris theatres as well other festivals in France (Montpellier for one, just prior to Avignon). The possibility that they might actually close down the festival was very real (they had successfully done so in 2003). Throughout the festival, they voted regularly on whether or not to strike specific shows. Olivier Py voiced his support for their cause but he made it clear that he was against their shutting down any shows. “The best way to further our cause is to let the show go on,” became a rallying cry on the part of some of the “intermittents” who were invited to begin each performance with a moment of protest against the government. Artists and festival staff all wore small red felt squares in solidarity with them. Even so, both shows on opening night, July 4, were canceled one because of rain but the other, by the strikers. It was a rude beginning for the festival’s new director. Fortunately, the shows went on for the most part. Arriving in Avignon on July 9, I began my daily visit to the festival offices to see what shows would play that day. I was lucky to see most of everything I had programmed.

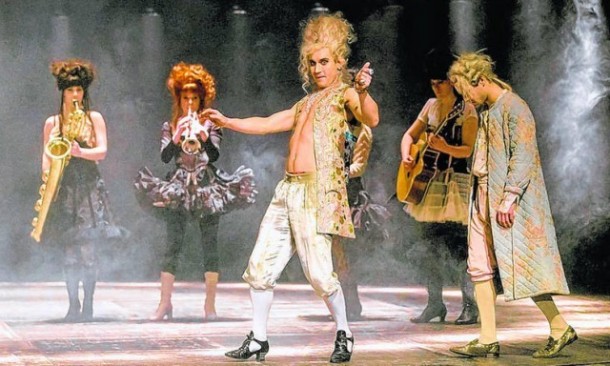

In keeping with Olivier Py’s goal to introduce festival audiences to emerging creative artists, this year’s program of fifty seven shows included a number of works by young, little known artists. Twenty seven year old Lazare Herson-Macarel and his young cohorts (the youngest company in the official festival) were invited to present their lively, fun filled Falstafe, an adaptation of well known playwright Valère Novarina’s 1975 Falstafe, which is itself an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Parts I and II. Falstafe was billed as a play for young people over the age of 9, but the audience was clearly all ages and they definitely enjoyed the antics of this delightful farce. Lazare Herson-Macarel and his friends come from Fontaine-Guérin, in the Maine and Loire region where they founded the Théâtre Nouveau Populaire festival in 2009. Theirs is an open air theatre “open to everyone every day.” They brought this spirit to Avignon.

Five performers in their mid-twenties (likeable youths, the name they have given their company), play all of the roles in this tale of King Henry ‘s son and his fat, degenerate, cowardly, companion Falstafe (interpreted by Joseph Fourez). Their stage is filled to brimming, with a supermarket cart full of food, plastic bags and packages, a large armchair and lamp that look like they came from the Salvation Army and a tall ladder. Above the ladder, a huge sign announces that “La Jeunesse doit Vivre” (“Youth Must Live”) and indeed they are living it up dancing around on the stage, enjoying themselves before they must play their roles: Henry the King of England, the Prince, his son, Percy (son of the Count of Northumberland), Captain Pistole, Worcester, the Hostess, and of course Falstafe, who noisily rises up from a red garbage bin where he has no doubt been sleeping off a night of reveling. Wearing a tee shirt with a map of North and South America, he devours an ice cream Sundae dripping with whipped cream. An Ubuesque figure, he is the image of gluttony and avarice. He puffs himself up as a brave soldier but cowers from a scarecrow with a pumpkin head that appears out of nowhere. The play moves forward in a series of chapters with titles (another reference to Alfred Jarry’s Ubu?). Chapter 3, for example, entitled “Comment il s’évade tout seul.” (“How he escapes all by himself”) has Falstafe recounting the battle in which he fought off one hundred adversaries with his mighty shield (a garbage can top). “Ils étaient cent contre moi ….,” he boasts. There were a hundred of them, he claims, when in reality there were only two.(echoes again of Ubu but also Rodrigue’s battle narrative in Pierre Corneille’s Le Cid.)

Chapter 4, “A war between Henry IV and Percy,” offers actor Julien Romelard a chance to show his “stuff’ as he executes a remarkable tour de force performance as both Henry and Percy in a battle to the death. In Chapter 8, Falstafe dies but of course he comes back. Throughout there are duels with kitchen utensils and soup ladles, and whipped cream pies thrown in the faces of the enemy. Falstafe goes to war wearing a plastic colander for a helmet. Finally, Prince Henry becomes the new King of England and the stage is emptied of all of the litter but for a police barrier behind which the cast waits to see Henry crowned. Falstafe, an old man, stands alone, mumbling to himself, his head bowed. Youth prevails. In just over an hour, Lazare Herson-Macarel and his merry band, as young as they are, proved themselves masters of pantomime and slapstick comedy.

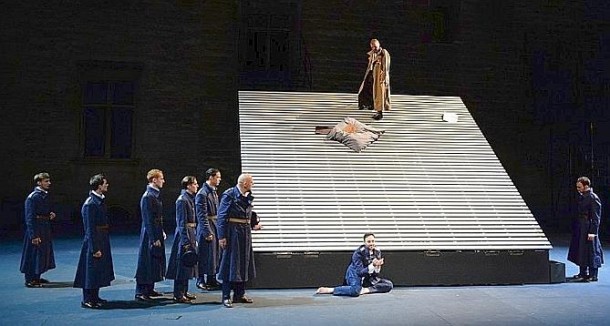

Heinrich Von Kleist’s Le Prince de Hombourg, directed by Giorgio Barberio Corsetti. Photo: courtesy of author

The festival’s opening production in the Honor Court of the Popes’ Palace, Heinrich Von Kleist’s Le Prince de Hombourg, directed by Giorgio Barberio Corsetti, was a much anticipated event. Many still recall this piece as one of Jean Vilar’s great productions, starring Gérard Philipe as the prince, Jeanne Moreau as Nathalie and Jean Vilar as her uncle, the Grand Elector. It was much admired by both critics and public in 1951 and has remained an important reference in the history of the festival. One can watch a video of this mythical performance at the Maison Jean Vilar in Avignon. Comparisons were inevitable in this town where the early years of the festival have become legendary.

Kleist’s historical drama about a young prince who disobeys his military orders during the battle of Fehrbellin in 1675 and is sentenced to die for insubordination, is tailor-made for the Honor Court audience which enjoys a good romantic tale featuring a handsome tragic hero who confronts authority and wins his lady’s love. The theme of disobedience to authority is central to the play. Hombourg had led his fellow officers to victory against the Swedes but his triumph was the result of disobeying the Grand Elector’s orders not to engage the enemy without a direct order. In fact, he had not heard that order since he was in such a dream state when it was issued. The Grand Elector is intransigent in his condemnation of Hombourg’s act and his decision to have him executed. Colonel Kottwitz, on the other hand, persuasively argues with him that the only thing that matters in war is victory. Count Hohenzollern, Hombourg’s friend, dares to tell the Elector that it is the Elector’s fault that Hombourg did not hear the orders. Hombourg agrees with him at first, but, in a very emotional and moving scene, he tells his comrades that the sacred law of the army must prevail. He wishes to glorify this law by freely choosing to die.

Corsetti chose to downplay the historical aspect of the play and stress the more contemporary issues raised by Kleist’s drama. It may be farfetched to speak of Hombourg’s dream-like state, his confusion about where he is, his outburst when he first encounters Nathalie that frightens her away, as battle fatigue (or even post traumatic stress disorder in today’s terms) but as played by Xavier Gallais in the early scenes, exhausted, dazed, disoriented, not knowing where he is or what he is doing, it is a reasonable interpretation. Equally interesting for the contemporary audience is the discussion about the authority of the state versus the individual’s right to question it. The comparison with the “intermittents’” fight against the government’s decision to change their status was inevitable. The difference of course is that the Prince faces the very real possibility of death. His anguish and fear are palpable when he looks into the grave that is being dug for him by two men casually throwing the dirt on the wall, just doing their job. And his visit to his aunt, the Electress (movingly played by Anne Alvaro) is heart wrenching. He has seen his bones at the bottom of the grave; he is afraid and he feels abandoned. He pleads with her to save him, to intervene for him with his uncle. Some may see him as weak and a coward, but he is only a frightened child in the arms of his surrogate mother, who comforts him but to no avail.

Corsetti’s stage is dark and somber throughout the drama’s two and one half hours. The military garb of the Prussian army is mostly dark gray with black trim (with the exception of the little red felt square that they all wear in solidarity with the “intermittents”). The women wear more color (Nathalie in off white and silver/gold, and her aunt, the Electress, in maroon), but for the most part, Hombourg moves forward in dim light. The set is dark as well with its large dark gray platforms, big multipurpose frame and staircases leading up to courtyard’s south wall. There are scenic elements that add variety to the stark set: giant images projected on the wall provide the illusion that the Grand Elector’s fortress-like palace is behind the framed entrance way, or a huge frightening figure made of five hideous masks of the men who will judge Hombourg at his Court Marshall. And the most awesome of all these images is of Hombourg riding off on a giant white horse, thanks to a stunning projection of the horse with its long legs and mane flying in the wind.

At first, news of the great victory against the Swedes is cause for much rejoicing, but before long the Elector asks Hombourg for his sword and sends him to prison. Nathalie pleads with her uncle to spare this noble, brave prince and a petition to free him is signed by all of the officers. Finally despite his conviction that one must follow orders, the Elector agrees to offer clemency to Hombourg. At the play’s climax, Hombourg is blindfolded and ready to die. Nathalie takes his blindfold off and puts the laurel wreath on his head. It’s no wonder that he faints, having thought that he was about to be executed.

Instead, his fellow officers carry him over to the large frame and string him up on it, like a puppet. “Hail O Prince of Hombourg,” they all shout in praise of the hero prince, but the audience is left with a very strange and demeaning image of Homboug dangling in the air with his sword in his hand.

Robyn Orlin’s At The same time We Were Pointing A Finger At You, We realized We Were Pointing Three At Ourselves… Photo: courtesy of author

In contrast to Kleist’s dark tragedy South African choreographer Robyn Orlin’s At The same time We Were Pointing A Finger At You, We realized We Were Pointing Three At Ourselves… was all color, exuberance and fun. Created with eight male dancers from Germaine Acogny’s l’Ecole des Sables in Senegal, (JANT –BI), Orlin’s objective was to explore the reasons for the lack of representation and discourse about the body in Africa. Working with these dancers, she hoped to find answers to the reasons for this inhibition and why African men fear homosexuality.

Her set features wonderfully colorful basins in all shades of red, peach, azure, and yellow, that are stacked initially on shelves in the middle of the stage. A pretty teapot sits on top of them. Birds are chirping. There are ropes hanging here and there and we hear the loud braying of donkeys. We are in an African village soon to be visited by a group of eight dancers dressed in hoodies, royal blue and red gym outfits, bright yellow gold baggy pants, and wearing sun glasses and flip flops. They climb into the audience shouting at us in English, French and Wolof. One of them takes a selfie on his iPhone and proceeds to tell the friend he is talking to on the phone that he cannot talk now because the theatre is filled with people. Another shouts: “Stop! Ils ont oublié mon solo!” (“They forgot my solo!”). Room is made for him to sing: “Two little eyes to look with, two little ears to hear, and one tiny nose to smell and a tiny mouth that speaks.”

No sooner do we have a chance to take in the meaning of these moments when there is thunder and lighting and all of the basins fall down. It is now time for the dancers to busy themselves with lining up the basins and tying them together, all the while making music as they work. It is especially appealing to see how they can make music out of anything, slapping their bodies with their flip flops or singing into the pretty basins, and making chirping sounds with their hollow cheeks.

A large imposing photo of Germaine Acogny, seeming to watch over her dancers, is shown while from time to time such cryptic messages as “Robyn a quelque chose pour vous.” (“Robyn has something for you”) appear on a screen. The something is clothes or rather costumes that drop down from above. It is time for the ceremony of SIMB (or fake lion in Wolof), an initiation rite villages hold to celebrate their community. The scenario is about a lion born in the forest who is orphaned when his parents are killed by wild beasts. It is a rite interpreted exclusively by men, two of whom are dressed as women. Wearing animal skins made out of toys, pink bunny ears, and a mask made of safety pins, they entertain the audience (positioned as the villagers) with dancing and music, and most enjoyable, with their high spirits. It would seem that Orlin accomplished her objective as these jubilant male dancers take on their female roles with such gusto.

Satoshi Miyagi’s Mahabharata-Nalacharitam was one of the highlights of the festival. Held in the same quarry where Peter Brook presented his unforgettable Mahabharata from dusk to dawn in 1985, this performance was much shorter (about two hours) but equally breathtaking. While Brook told many tales from the ancient Sanskrit Indian epic, Miyagi opted for just one, the Nalacharitam, a love story without battles or fighting. To tell the story of the love between King Nala and Princess Damayanti, Miyagi transposed this episode to tenth century Japan during the Heian period. Twenty five performer/dancers, musicians and singers—all of them superb—held the audience spellbound throughout.

Thanks to a circular platform above the audience, we enjoyed an uninterrupted view of all of the many dazzling scenes of this intriguing tale. Drums roll and silhouettes appear far above the quarry; the performers are making their way down to the platform. Dressed in splendid white sculpted paper costumes, they move slowly forward on the platform to begin the telling of the Nalacharitam. A narrator (the legendary Kazunori Abe) speaks the lines of most of the characters who make the accompanying gestures.

Four Gods in masks and magnificent white costumes, have come down from the Heavens to attend the wedding of Princess Damayanti and King Nala. They bless the couple and wish them happiness. A masked character, the Demon Kali, with hooked nose, announces his intention to get rid of the King. He casts a spell on him that will result in his downfall. Meanwhile twelve years go by and the happy couple have two children, a boy and a girl. Life is good. Such happiness and good fortune cannot last, however, and the Devil will exact his due.

King Nala’s brother arrives with much fanfare, accompanied by his entourage wearing white neutral masks and carrying majestic red flags. He talks Nala into a game of dice. Nala loses again and again but he cannot stop playing. He loses his 1,000 elephants, his 60,000 soldiers, all of his slaves and finally his throne. Only his dear wife and children are spared but they must live in exile, far from Nala and their home. Before parting, Nala takes one of his wife’s sleeves, the only memento he has of happier times. Damayanti finds work and shelter but Nala must wander through the forest alone and abandoned, the prey of wild animals and serpents (all beautifully represented by clever paper puppets, a very hungry tiger and a famished python who no doubt want to eat him).

In one stunning scene after another, performed in a mixture of Japanese performance styles, Kabuki, Bunraku, No and Kaishibai, the audience is treated to snippets of the world beyond the hero and heroine’s odyssey. A jaunty wagon merrily makes its way along the road path, for example, while a caravan of merchants with their paper camels pops up out of nowhere. Unfortunately for them, they are trampled to death by a herd of elephants suggested only by giant trunks held high like flags by the wonderful performers. In the end, Nala, Damayanti and their children are reunited and all is well as the mostly female orchestra underscores their joy with vigorous drumming.

Festival director Olivier Py is the first Avignon director since Jean Vilar to be a creative artist, playwright, actor, and theatre director. His name appeared on three of the productions in the festival, as director of Vitrioli, by Greek author Yannis Mavritsakis, performed in Greek, as author of La Jeune fille, le diable et le Moulin, a musical play for children based on the Brothers Grimm’s tales, and his latest play, Orlando ou l’Impatience. Orlando is a modern comedy ostensibly about a young man looking for his father. His mother, a flamboyant actress teases him into thinking she can remember which theatre director she slept with who might be his father. “Your father’s name is written in lipstick on my mirror,” she tells him several times, but he never finds the name there. Frustrated, he demands the list of directors invited to the inauguration of the Chrystal Palace where he believes his father met his mother.

For close to four hours, Orlando searches in vain through encounters with various characters; a young woman (the ingénue), a theatre director, a crazy speech professor who embodies many other characters, all of them crazy, various fathers, a lascivious Minister of Culture and more. All of these chance meetings occur on a visually exciting set all in black and white created by Pierre-André Weitz. Its revolving stage, framed in white neon, allows Orlando to travel from city to city and from theatre to theatre as cityscape drawings in black and appear and disappear. Among the many characters he meets is a sado-masochistic Minister of Culture, a vulgar, portly fellow who exchanges his favors for other “favors.” He is disgusting, whereas the speech professor is quite funny. He claims that people’s unhappiness (or misfortune) comes from the fact that they do not pronounce words correctly. Or at another moment, he says that people’s unhappiness comes from the fact that they don’t take enough magnesium.

Py’s Orlando is dense with ideas and words. It is not always easy to follow, but in essence his play is about theatre. Each time Orlando meets a potential father, he discovers a potential form of theatre, political tragedy, erotic comedy, historical epic, and philosophical farce. Years go by and Orlando becomes the director of his own theatre. He has earned the Legion of Honor but he finds no pleasure in his success. His dream of finding a theatre of joy seems to have been just a dream. In the final scenes, Orlando is homeless and destitute. He has not found his father, or has he? The Poet, who speaks to him from his window, is on his way to become director of the Chrystal Palace where his mother most likely had met his father. But it is too late.

Huis, a musical theatre piece directed by Belgians Josse De Pauw with music by Jan Kuljken, is a diptych composed of two short plays by Michel De Ghelderode, Le Cavalier bizarre (The Strange Rider) and Les Femmes au tombeau (The Women of the Tomb). Both plays are meditations on death, performed by superb actors. The first concerns impending death, the second, takes place after a death has occurred. Huis means house in Dutch and door in French and in both plays, the characters are enclosed in some sort of dwelling.

In Le Cavalier bizarre, the more engrossing of the two plays, six old men in white nightshirts have reached the end of their lives. They might be in a hospice. They are lying on a white platform with pillows spread around them and white sheets covering them. One with white hair and beard (Josse de Pauw) gets up from his bed and puts on a colored print dress. He skips around showing off his outfit to the others as they stir from their sleep. One of them begins to hear bells but there are no bells in that area. Perhaps these are the imaginary bells tolling the arrival of death. Before they die, the man in the dress performs a graceful dance and they all join in. Watching them slowly turning and twirling to Kuljken’s music is very moving. Despite their age, they still find the strength to bring out a large wooden ladder. One of them, the watchman, manages to climb up to the top to look out. “I see the field and the fog,” he says, “and a huge horse.” The horse’s strange rider has bells around his neck and he is headed for their house. We hear the sound of a door opening, and footsteps. They panic. Hiding under their sheets, and confessing their sins, they plead with Death not to send them to Hell.

It turns out that Death was not coming for them after all but to pick up a child and the play ends with the old men having a good laugh. The men from the first play set the new scene for Les Femmes au tombeau by bringing in wooden benches and placing them here and there on the empty stage. These “women in the tomb” are the women who followed Jesus during his life. They are now gathered in the house of Mary the day after his crucifixion. As the play opens, they are asleep on the wooden benches. As they begin to stir, we learn who they are: the adulterous woman who was going to be stoned, Mary Magdalene; Mary, Jesus’ mother, who is so distraught that she crawls rather than walks across the stage; and another who has come from Golgotha where she witnessed the horror of Christ on the cross. They exchange their feelings about this terrible loss and share their experiences of having known Jesus. At first they comfort each other, but before long, the accusations and recriminations begin. From compassion “he was too young to die” to blame (“one of them stole the holy image”), they weep in choral unison, shut up forever in a tomb of their own making.

Antú Romero Nunes, another one of the festival’s younger directors, brought his punk Don Giovanni, Letzte Party to Avignon’s Opera House. For many in the audience it was a delightful last party. On a vast empty stage, Leporello appears before us wearing a pastel colored frockcoat that looks more like a pink and white bathrobe. He clears his throat and gets the audience to practice scales with him. Their enthusiasm grows as he runs around the audience listening to each one. When he is satisfied with the results, he gives a whistle and out come seven gorgeous girls with musical instruments. They are the orchestra who will provide the music, a mixture of rock and pop, not Mozart. More beautiful women appear, one in a pink and red sleeveless dress, another in a lacey eighteenth century costume, another in peach and aqua. They herald the coming of the great Don Giovanni bedecked in pink stockings, a flowered silk coat, a ruffle and a huge wig. Everything is fun and games. Nothing is taken seriously even when Don Giovanni kills Rosina’s father as they all sing along. Not to worry. It’s no big deal since the father gets up laughing.

A later entrance is even grander. A gigantic light fixture comes down from the flies looking for all the world like Steven Spielberg’s spaceship in Close Encounters of The Third Kind. With much smoke and fanfare, out steps Don Giovanni ready to seduce Zerlina (who is happy to be chosen) and boast of his conquests to poor Dona Elvira (1,003 women in Spain). These are familiar stories in the Don’s trajectory, but more important to him than the pleasures of seduction, perhaps, is his commitment to freedom.

Antú Romero Nunes’ Don Giovanni is neither an opera nor a musical, it is one big party. In a surprising finale, the Don invites everyone in the audience to join him for champagne on the stage, regardless of social status. He really cares about everyone joining together in celebration. Some accept the invitation, others do not, a fitting example of freedom of choice. “Viva la liberta!” they all sing as the show receives wild applause.

My favorite show of the festival was Ivo van Hove’s exhilarating adaptation of Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel The Fountainhead. Thanks to van Hove’s superb staging and his extraordinary actors, I spent four fascinating hours revisiting familiar characters from Rand’s controversial novel: Howard Roark, a brilliant young architect who answers only to himself; Peter Keating, Roark’s exact opposite, a fellow architect who sells himself for commercial success; Guy Francon, head of the biggest architectural firm in New York City; his beautiful independent daughter Dominique, who is passionately in love with Roark but marries both Peter Keating and Gail Wynand, a wealthy newspaper magnate; and finally the powerful art critic Elsworth Toohey, whose art reviews in Wynand’s newspaper, The Banner, can destroy anyone he pleases.

Van Hove‘s production follows the novel chronologically but with fewer characters and a much reduced text. He uses the entire vast stage of the courtyard of the Lycée Saint-Joseph, to recreate several different playing areas: Francon’s architectural firm, Elsworth Toohey’s office, a drawing table where Roark creates his magnificent buildings, a table where Peter Keating’s mother serves tea and much more. As the play opens, a number of men in white shirts and chinos are milling around. Some of them are the ever-present technicians, video artists and designers who make magic happen on van Hove’s stage. Others are probably architectural students in the school where Roark and Keating are students. The cover of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead is shown on a screen as an actor reads the first chapter entitled “Peter Keating.” Peter’s mother is serving tea in the middle of the stage. We learn that she wants her son to join Guy Francon’s firm in New York. Roark moves to New York as well hoping to work with Henry Cameron, an architect of modernism. Cameron has been ostracized from the architectural world because his designs are too modern. Cameron warns Roark that he will never succeed in getting his designs built in the 1920s conservative arena in which they both work. Cameron dies leaving Roark without a job. A short stint at Guy Francon’s firm inevitably leads to conflict and Roark is quickly fired, left to find work as a laborer in a construction quarry where Dominique Francon sees him for the first time. But these and many more are only details in the ongoing saga of Peter Keating’s rise to the top of his firm by following the latest fashions while Roark remains true to his ideals. What is so thrilling about this production is not only the superb acting but also, and equally superb, van Hove’s technical wonders. Thanks to set designer Jan Versweyveld’s wizardry we fully live the illusion of watching real architects design sketches in real time, possibly using transparencies and tracing paper with cameras recording the action and projecting the images on surrounding screens. Ramsey Nasr who plays Roark had to take drawing lessons in order to be convincing and he succeeds beautifully.

The scenes of passion between Roark and Dominique are the most sensual and carnal that I have ever seen on the stage. Their first sexual encounter is actually rape. Roark grabs the beautiful but cold Dominique (Halina Reijn), takes her to the back of the stage and violates her in the semi-darkness. Van Hove leaves nothing to the imagination as Roark tears off Dominique’s stockings and takes her from behind. We see all of this in a larger-than-life image on a big screen. Although Dominique tells Roark she detests him and will destroy him, their passion consumes them as much as they fight against it. Other scenes of their lovemaking are equally powerful, but the most powerful of all is when Dominique blows up the public housing project at Roark’s request (he designed the project but cannot allow anyone to change his design). The explosion alone was breathtaking and truly frightening. The blast is so unexpected and so huge that we experience it as very real, not an illusion. We see windows breaking, tables and papers flying across the stage, and the entire set being blown up in front of our eyes. Dominique lies on a drawing table below the front of the stage, clearly having just experienced an orgasm, her blood soaked body shown in close-up on a screen. For van Hove, this is the first time that she is capable of giving herself to another person and it is a major turning point in Dominique’s life.

Other scenes are equally powerful, especially the moment when Gail Wynand, determined to continue publishing articles in favor of Roark’s buildings, stands beside a gigantic printing press while his workers are in the street striking against The Banner. With the help of one remaining colleague, Wynand starts the presses rolling. The loud sounds of the unwieldy machine fill the stage as what seems like hundreds of newspapers fly around the stage. Wyand (magnificently portrayed by Hans Kesting) explodes with rage, knowing that he will have to accept defeat.

Roark is Ayn Rand’s hero, the ideal man that she is promoting in her novel. He is cold and nothing can touch him. She treats Peter Keating with total distain. For van Hove, on the other hand, these are two flesh and blood characters who represent the role of the artist in society, whose choices have to be taken into consideration, not rejected. In his view, he wants these two characters to be more in balance. Roark’s belief may be admirable but to be a citizen in today’s society, total individualism is not possible. It is important to live together, adapt, and compromise, van Hove told a group of festival audiences. You have to choose to be a citizen.

Denis Guénoun’s Mai, Juin, Juillet, (May, June, July), a quasi documentary play based on those three decisive months during the events of 1968 when the May demonstrators occupied Jean-Louis Barrault’s state-run Odéon theatre and questioned the validity of Jean Vilar’s Avignon festival, was a must see for anyone interested in that important historical moment, especially in the context of the threat to this year’s festival albeit for different reasons.

To recreate the urgency and excitement of the occupation of Paris’ Odéon theatre, director Christian Schiaretti, current director of the Théâtre National Populaire in Villeurbanne, used the side boxes and stage of Avignon’s traditional opera house architecture, to full advantage. As the play opens, his stage is filled with empty chairs. It is May 15th and suddenly what seems like hordes of young people appear in the loges and gather on the stage. A young man has just arrived from Caen. He does not know what is happening. They fill him in on the background of the May revolution and their reasons for taking over the theatre.

Enter Jean-Louis Barrault (beautifully captured by Marcel Bozonnet), hoping to welcome them but also reason with them about protecting the costumes and theatre. They turn their back on him. Madeleine Renaud, umbrella in hand, stands speechless as the demonstrators leave and Barrault stands alone. Using the conceit of sharing his experience with Vilar, Barrault reads from a fictional letter he supposedly wrote to the Avignon festival director. He is a broken man, disillusioned by the revolutionaries’ refusal to hear him. “I was thrown out,” he writes Vilar. And even more painful, André Malraux, the Minister of Culture who appointed him director of the Odéon, turned his back on him. “Malraux the magnificent…”

The second section of Mai, Juin, Juillet takes place at Roger Planchon’s Théâtre National Populaire in Villeurbanne, where twenty-three directors of the Maisons de la Culture and public theatre centers in France gathered to draw up a common declaration of what they intended to do to change the cultural wasteland they believed their theatres had become, Their mission was to bring the working class—the “people”—to the theatre and they had clearly failed. Dressed in dark gray suits with conservative ties, the group discusses ways of reaching what they agreed to call “the non public,” the large numbers of French people who do not go to the theatre. There is little action and much arguing in this scene which makes this section much less engrossing than the other two. Surprisingly there are no women’s voices, no female directors of France’s subsidized theatre to speak for the many women who also were not part of their audiences.

In the third and final section of the play, we meet Jean Vilar (in an extraordinary performance by Robin Renucci) in the most moving and significant part of the four hours of Mai, Juin, Juillet. Renucci looks like Vilar and talks like Vilar; he has the same gestures as Vilar. It is a crucial time, just after Vilar and his festival have been unjustly attacked by the demonstrators, who failed to understand that Vilar was on their side. All of his efforts to talk to them had failed. They were determined to destroy the festival calling it a “supermarket of bourgeois culture” and shouting “Vilar Salazar.” We see him here as a lonely figure wandering the streets of Avignon at night. A young girl, one of the protestors, appears out of the shadows and they talk about what happened at the festival. Vilar tries to dialogue with her, but she turns a deaf ear. This poignant scene neatly dovetails with Barrault’s early statements even though the two men were on opposite sides politically.

In the midst of so much controversy, and all of the challenges Py had to face, it was refreshing to attend a “reading” of a new play by Bernard Faivre d’Arcier, former director of the Avignon Festival, entitled Avignon : codes-barres. “Performed” (essentially read) by Faivre d’Arcier himself, Jean-Damien Barbin (a key actor in Oliver Py’s Orlando ou l’impatience) and well-known actor Michel Didym, at the Maison Jean Vilar, the show was great fun, a too short hour offering remedies and advice to emerging artists as well as audiences who learned how to obtain and keep subsidies, how to get comps, how to read the critics without fear, how to applaud, how to talk to a Minister of Culture and many other useful tidbits.

In box-office terms, the 2014 Avignon Festival did better than might have been expected given the cancellations and the bad weather. There were 131,728 tickets sold and attendance was at 90 per cent capacity. Out of 289 shows, 277 actually took place; twelve shows were cancelled by the strikes and two because of rain. Still the festival now has a debt of 300,000 Euros which the government is unwilling to cover and Py is talking about having to shorten next year’s festival. When asked how his first experience as director of the festival went; he quoted Vilar: “Cela n’a pas été simple, mais cela a été beau.” (“It wasn’t easy but it was beautiful”).

, is Professor Emerita of French Language and Culture and Drama Studies at Purchase College,State University of New York. She writes widely on contemporary theatre and performance and is the author of Le Théâtre populaire selon Jean Vilar (Actes Sud, 1991 and 2012), Drama Contemporary: France (Performing Arts Journal Publications 1986) and Act French: Contemporary Plays from France (PAJ Publications 2007). She has translated numerous contemporary French language plays (by Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute, Philippe Minyana, José Pliya, and others). Her latest activity is translating contemporary New York theatre productions into French for supertitles (the work of ERS, Kenneth Collins, Jay Scheib, Basil Twist, Okwui Okpokwasili,Tina Satter, and Christina Masciotti). Dr. Wehle is a Chevalier in the French Order of Arts and Letters.

European Stages, vol. 3, no. 1 (Fall 2014)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

• The 68th Avignon Festival 2014, July 4 to 27: Protests and Performances by Philippa Wehle

• The Avignon Fringe Festival 2014 by Manuel García Martinez

• The Reality Bites of New Bulgarian Theatre by Dessy Gavroliva

• Happy Days: Enniskillen International Beckett Festival 2014, July 31-August 11 by Beate Hein Bennett

• Flemish Theatrical Exceptionalism Mostly Glimmers, Sometimes Wavers by David Willinger

• Shouting at the Devil (and Everyone Else): Yaël Farber’s Production of The Crucible at The Old Vic by Erik Abbott

• Mladinsko Theatre and Oliver Frljić’s Damned Be the Traitor of His Homeland! (Sibiu International Theatre Festival, Romania, 2014) by Ilinca Todoruţ

• Barcelona Theatre (2013): Responding to Spain’s Crisis by Maria Delgado

• Report from Madrid by Duncan Wheeler

• Irish Colonial History on the Hungarian Stage by Mária Kurdi

• Fantastic Realities: Actors as Puppets and Puppets as Actors by Roy Kift

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2014 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016