The Avignon Fringe Festival took place between the 5th and the 27th of July. If the Avignon Theatre Festival is one of the biggest of the world, it is due to the Fringe Festival. The dimensions of the Fringe Festival were impressive. In 2014, there were 132 theatre stages within Avignon, most of them inside of the historical walls of the city, where more than 1300 productions were performed. The organization of the Fringe Festival estimates that the number of spectators in the festival of 2013 was 1,330,000. It is thought that the number was much larger in the 2014 festival.

Each theatre organizes its own production, which is completely independent from the central organization of the Festival. Each theatre program is organized in slots of time of more or less two hours: the space is rented to the companies which want to present their production, most of the time for three weeks. The price for renting the theatre during a slot is not publically revealed: it seems that depending on the theatre space, the price ranges between 4,000 and 15,000 euros, and that it can even reach 30,000 euros for the most important theatres. Each theatre group that rents a stage has to bring its own technicians and take on the selling of tickets and the publicity of their production. The organization of the Fringe Festival estimates that in the 2013 festival each production handed out an average of 8500 flyers and put up 400 posters. During the 2013 Fringe Festival, the average budget for each production was 21,500 euros.

An average of fifty-four percent of this budget come from the sale of tickets and thirty-four percent was an investment made by the theatre company. Therefore, the economic stake for most of theatre companies is very high, and many actors are distributing flyers after or before they perform. If success is achieved, the production can be seen by journalists of the most important French and international newspapers and sold to a large number of theatre program planners in France. In fact, according to the information given by the Fringe Festival, each French program planner buys an average of four productions during the Fringe Festival, which means twenty percent of its program for the following theatre season. Sixty percent of the theatre companies that were in the 2013 Fringe Festival have participated at least twice and fourteen percent of the French companies come every year to the Fringe Festival. The spaces begin to be rented in September of the previous year, and some theatres sell out all the slots and close their program in January. The Fringe Festival official program is published in May.

In 2006, an association, Avignon Festival & Compagnie, took over the coordination of the Fringe Festival; it is in charge of the publicity for the overall Festival (the Fringe Festival program has existed since 1982, but before that was published by Official Avignon Festival). Since 2010, this association has been located in the “Village du Off,” rue des écoles, a building with a large courtyard, reserved for the Fringe Festival Organization. Following the general tradition of Fringe festivals, the organization does not establish any hierarchy among the productions, and the employees of the Fringe Festival are forbidden to express their opinions about the quality of the productions.

The great diversity of productions allows any spectator to choose the productions he wishes to see. But the problem in the Fringe Festival is to know what productions are interesting from a theatrical point of view. The most important French newspapers, besides the local ones, are in Avignon during the Festival; they review a large number of productions every day, but the amount of information is so great, and most of the time so contradictory, that it is very difficult to know what the really interesting ones are. Like a fisherman in the sea, the audience can, in one day, find and watch a few excellent productions or return without any good catches. Nonetheless, during the last week of the Festival, a hierarchy appears and the best productions are sold out, while the less interesting ones have hardly any spectators. By staying in Avignon during almost all of the Festival, checking the press daily, and listening to the opinion of other spectators by word of mouth, I am convinced that I have seen some of the most interesting productions, but also inevitably have missed others: the productions reviewed in this article are the result of my personal choice.

L´école des ventriloques (The School of Ventriloquists) by Jean-Michel d´Hoop, presented at la Patinoire. Photo: V. Vercheval

There is fantastic diversity of productions. All the theatre genres are represented. The Fringe festival program classifies them as: Theatre “de Boulevard,” “café-theatre,” sounds, circus, clown, concert, dance, dance-theatre, puppets, mime, musical productions, and musical theatre. All the dramatic genres (comedy, tragedy, poetic drama and so on) and a number of the important French playwrights from the nineteenth and the twentieth century are represented. Most of the productions are humorous.

The Fringe Festival could also be the place to look back on theatre history. One can see diverse acting styles and also techniques that had once been important but that today belong to theatre history more than to the modern stage. One can watch the best and the worst side by side. Beside elaborate productions thought to convey an idea to which the theatre gives form, strength, and meaning, other productions are based only on the actor´s presence, sometimes with almost no directing.

The economic situation means that a great number of productions have only one or two actors. As a consequence of the theatre timetable, divided into tight slots, the sceneries and the props are most of the time very simple, as they have to be removed immediately after each production. The staging is most of the time limited to its essential elements: the actor, his acting, the relation with the audience, the quality of the text, a basic lighting, and an elementary soundtrack. Thus, though it presented thousands of stories, like the shining squares of diverse colors of a vast mosaic, the Fringe Avignon Festival 2014 was not noticeable for its scenic innovations.

The theatre in the street

In Avignon the theatre is primarily in the streets. In almost all parts of the city and until late in the evening, actors of all ages, disguised with vivid colors, alone or in groups, advertise their production to everyone who is willing to listen to them, handing out flyers. Every one of them tries to catch the attention, the emotion, and the curiosity of the potential audience. They all hope that word of mouth will bring more spectators. At the Place des Carmes, a young actress moves around inside a huge plastic ball; a little bit further on, an entire group, with its medieval costumes, is parading; close to the Theatre du Verbe Incarné, on Saturday the 19th at 6:00 p.m., three actors, almost naked, covered only with a painting that reminded us of Butoh actors, had stopped a car, crawled onto it, and tried slowly with awkward movements, to climb on it, under the glances of all people around. The medieval streets are crowded for most of the day; some people strolling while others are rushing so as not to miss the beginning of the next chosen production. But there are also narrow streets of this medieval city where one can be alone, and in the afternoon, when the sun is at his highest point, the city seems to sleep for a few moments.

The monologues

Among the most remarkable productions, a few monologues deserve to be mentioned. They all achieved great success among the audience. I think that the monologues could be classified by those which have an autobiographical feature, those whose fiction deals with a problem of the contemporary world, and finally, those that put the life of an author on stage and very often present various aspects of his poetry.

In the first group of monologues, Un, a Quebequois production by Mani Soleymanlou, who was also the unique actor on stage, presented at the Manufacture was very interesting. Un is the first production of a trilogy (Trois the third one has been presented this spring 2014 at the FTA (Festival des TransAmeriques) in Montreal.

It is a brilliant, very funny monologue about the origins and the definition of his own national and personal identity. Mani Soleymanlou speaks of his immigration from Iran to Paris, in France and then to Toronto. There he went to high school with many other immigrant children, to Ottawa, and finally to Montreal, where he studied in an acting school. Very well performed, always with very good rhythm, besides many silences during which the actor reflects on his life, the actor succeeds in capturing the attention of the audience. On a stage with twenty-five chairs like a classroom used to evoke the absent characters of his story, Mani Soleymanlou narrates comic episodes of his life: first as a child and a teenager, then as a young adult, through which he had the feeling of having multiple national identities. His movements in the space and the situation of the chairs defined the sequences and the progression of the production. After experiencing the problems of living in Canada, he felt the anxiety of defining himself in relation to Iran, where he used to come back for school holidays. He describes the oppression of the political power of the religion, the desire of young people to transform their country, and their frustration in not being able to do so. As he thinks about the situation in Iran he realizes, he has become Canadian. The confusion, the fear, and the desire to find a solution increase along the production. At the end, at an incredible pace, with a great comic effect, the actor mixes Farsi, French, and English very quickly. The production ends as he seems to have reached a solution: he is no longer Iranian, he defines himself a Quebequois actor, coming from Iran, and Iran belongs to the people of his own age, who live under oppression and try to change their country every day. Nonetheless, this Canadian problem of people coming from all the parts of the world, seemed a little bit strange on a French Stage.

Hors jeu, (Out of the game) by Enzo Corman, a production by Philippe Delaigne (and his company, the Fédération Compagnie Philippe Delaigne) presented at the Theatre de l´Alizé,, was an interesting production for many reasons. First of all, the actor was the playwright himself, Enzo Cormann, who is one of the most important French playwrights of the last thirty years. The theatre de l´Alizé itself commissioned Enzo Cormann to write a play. They asked him for a play about a current important issue in France and in the Western world: the suffering provoked by the economic crisis on long-term unemployed people, who being unable to get a new job, find themselves on the edge of society, “out of the game.” The text shows the last days of an engineer in long-term unemployment. From a literary point of view, the play mixes several genres: the social and political theatre, a plot close to the thriller and to film noir. A real news item was the inspiration for the play.

Hors jeu, (Out of the game) by Enzo Corman, a production by Philippe Delaigne (and his company, the Fédération Compagnie Philippe Delaigne) presented at the Theatre de l´Alizé. Photo: Géraldine Dolléans

The stage is very small, conveying a stifling atmosphere. The character´s distress is metaphorically expressed by the lighting: the space remains in the darkness during almost all the production, with a dim lighting, sometimes only the line of neon lighting that creates a back-lighting. The light flitters and changes in intensity reflecting diverse moments experienced by the protagonist. The sound track by Philippe Gordiani is based on noises and on electronic music and reinforces the effect of the character’s anxiety. The actor is alone on stage, and he speaks only with the speakers. Helpless, he hears via the speakers that he has been taken off the employment list, by the employment agency, because he refuses to accept a job below his qualifications. The man does not accept his situation. The distress and the paranoia causes him to get rid of his girlfriend (he gives her to a thug in exchange for a gun). He takes two women hostage, and he unintentionally kills one of them, before being killed by the police himself. Up to the end of the production, an increasing tension is built as the character moves between the darkness, showing his psychological destruction.

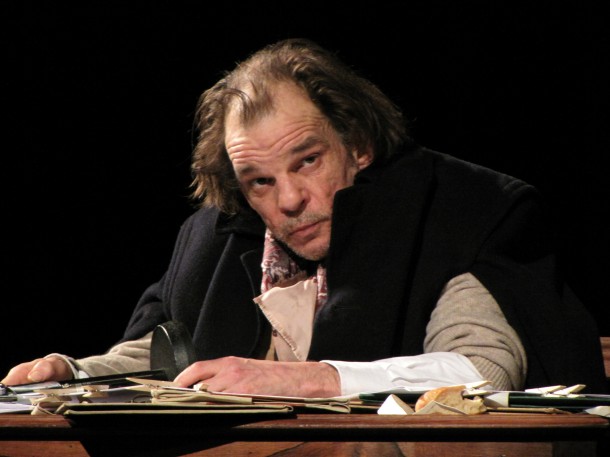

There are a great number of poetical productions, which present poems and writings of an author, often a part of his production, and the explanation of his poetry, especially how and why he writes. Among these sorts of productions, one of the most outstanding was Faire danser les alligators sur la flûte de pan (To make dance the alligators with panpines), based on the writings of Luis Ferdinand Céline, a production by Ivan Morane, with the well-known French actor, Dennis Lavant. This production presented in the Théâtre du Chêne Noir, has been one of the most successful productions of the Fringe Avignon Festival 2014, and undoubtedly one of the most striking and moving monologues.

Ivan Morane’s Faire danser les alligators sur la flûte de pan (To make dance the alligators with panpines), based on the writings of Luis Ferdinand Céline, with Dennis Lavant. Photo: Mélanie Autier

There are many reasons of this success. The adaptation is very interesting because it shows how Louis-Ferdinand Céline used to live and think at the end of his life. The text is solely based on letters and texts by Voyage au bout de la nuit´s author (Journey to the End of the Night). The actor performs these letters as a long monologue. The adaptation presents a few very important aspects of Céline´s poetry, about his style, what he used to consider important, the way he elaborated his novels, and his perfectionism. The adaptation also shows the personality of Céline, his attitude towards his writing, with respect to the economic aspects and the public´s reactions, his ideas about the political moment he lived though, and also about the authors of his time. The adaptation shows his political position, and ends with a sharp, violent, and insulting criticism of the authors of his time, such as Proust, Gide, Colette, etc., also mentioning the authors he used to admire such as Paul Morand.

But the production is mainly noticeable for the extraordinary acting of Denis Lavant, who succeeded in delivering the text and in keeping the audience´s attention until the end of a two-hour production, and also to reflect on the personality of the author, his reactions, his hates, his distress, his torments, and his deep loneliness. The actor creates an intonation very close to Céline’s, with the repetition of the same tics.

The production was divided into multiple sequences, during which the character, home-ridden, explains his thoughts to the audience, in front of whom he tries to defend his position with intensity and vehemence, but also with the scorn so frequent in Céline’s work. Between moments of speech, the actor carries out daily actions, such as writing on his table, playing the piano, lying in the bed, washing his face, hanging the sheets of paper he has first written on with clothes pegs on a string that is above his head. The audience follows the succession of writings as a stream of thoughts, and the intensity does not lessen at any moment.

A few miscellaneous productions

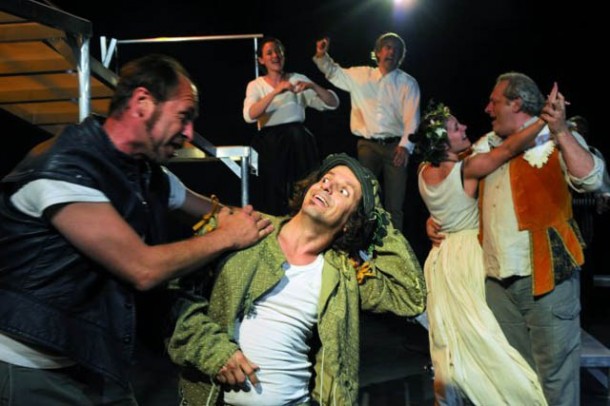

The audience unanimously acclaimed a few productions. Oblomov was among them, an excellent production inspired by the Russian novel of the same name (1859) by Ivan Gontcharov and directed by Dorian Rossel. Two diverse companies combined their efforts to create this production, O´Brother Company, a company associated with the Salmanazar Theater of Épernay, and the company STT (Super Trop Top), which is associated with Théâtre Forum Meyrin, in Switzerland. The production shows the story of an aristocrat, Oblomov, a good and honest man, but also somebody living in his dreams, lazy and aboulic. He symbolizes, for the director of the production, a parody of the Russian aristocrat of the nineteenth century. Oblomov lives in St. Petersburg, and he is unable to manage his properties; he is afraid to act and lives in a constant state of procrastination.

All the production is based on the excellent acting of Rodolphe Dekowski, Xavier Fernandez-Cavada, Elsa Grzeszczak, Jean-Michel Guerin, Fabien Joubert, Delphine Lanza and Paulette Wright, and is full of witty moments. Dialogues follow parts of scenes addressed to the public; the actors use a code, and abandon it as soon as the scene is over; in a few scenes, Oblomov is played by three actors—the actor who plays Oblomov, the one who plays Zakhar, his faithful servant, and another who plays his pragmatic friend, Stolz. This image of a multiple character seems to visualize his momentary strength and also his hesitations and his instability.

A large transparent plastic screen, bent to constantly reflect the actions that are performed in the front stage, divides the stage. The audience can also see the actors who pass behind the screen to play music and become for an instant witness to the main action as if they were part of the audience, on the other side of the stage. The stage elements are few: a square table, covered by blankets and duvets that represent the bed where Oblomov lies during the last part of the production. The changes are very quick: sometimes the actors play for few seconds, almost realistically, sometimes they mime the objects, while some others play an instrument of music or sing. The excellent adaptation is very dynamic.

The paradox of Oblomov´s personality and his hesitations deal with fundamental problems of the human being, in which every spectator can recognize aspects of his own life. For the director, Oblomov is today also the symbol of the search of a simple happiness without ambition, and the negation to submit his life to an epoch of productivism and frantic activity. The production brings up the questions about the relationship between activity and happiness.

Dorian Roussel´s main signature as director is, as he says, the constant adaptation of the text to the stage during the rehearsals, by a constant to and fro between the adaptation, the dramaturgic purpose, and the scenic realization, and this quality is very noticeable in the production. The production is happily paradoxical: it succeeds in showing a slow and calm main character and giving an important place to deep thoughts within a very dynamic production.

Claude Poissant’s Les cinq visages de Camille Brunelle (The five faces of Camille Brunelle), by Guillaume Corbeil. Photo: courtesy of La Manufacture

Les cinq visages de Camille Brunelle (The five faces of Camille Brunelle) by the very young Canadian playwright Guillaume Corbeil, in a production directed by Claude Poissant, was part of a special program of theatre of Québec (Canada), called “focus Quebec.” It was presented at la Patinoire (la “Patinoire” is an ice rink, in the outskirts of Avignon that is used as a second stage by La Manufacture). It was one of the most appreciated productions of the Avignon Fringe Festival 2014.

This production shows the relationships that five young people sustain—played by five very good actors: Julie Carrier-Prévost, Laurence Dauphinais, Francis Ducharme, Mickaël Gouin and Ève Pressault—in a social network (facebook or something similar). The production reflects how the network conforms their identity and also their relationships. The text and the production use clichés about the social network. The actors come on stage and speak directly to the public: they greet them individually, as they would have done in real life, and then begin to present themselves, explaining their tastes concerning food, clothes, drinks, holidays, and going out. The actors play in a line, side by side, in front of the public. They are together, but, at the same time, everyone is alone, isolated from the others. They look at the public, and they almost never address each other directly. The audience understands that the characters are communicating by the Internet, or through their cell phones: the actors look at the audience, as if they were looking at the screen of their computers. They only look directly at each other when a character corrects another, showing that he knows more or that he is stronger. They speak one after the other answering the same question that most of the time has not been formulated, and that the public will never know: they can only determine the questions by the answers. The messages are very often reduced to long lists of words or of actions that remind us of the lists used by Georges Perec in his novel La vie Mode d´emploi (Life: A User´s Manual). In fact, one of the characters mentions Georges Perec as one of the authors he likes the most. In these very long and eclectic lists, the characters show their mimetic tastes. They always try to upstage the person who speaks before them: their friendship is also a competitive relationship between them, always trying to show that they possess more (goods or knowledge) or that they know more fancy people. The characters express the opinion on many topics very quickly. They do enumerations, but almost never any commentary. The production shows how the Internet, text messages, and social networks create a dependency and also uniformity.

Claude Poissant’s Les cinq visages de Camille Brunelle (The five faces of Camille Brunelle), by Guillaume Corbeil. Photo: courtesy of La Manufacture

At the beginning the characters present their more positive side, while photos, showing them happy at a party, appear on the screen behind them. The screen is divided in five sections, in the downstage: “Me and…”, “me speaking with…” “me speaking with Camille Brunelle”: the characters define themselves by commenting on the images. They all speak about what appears at first to be a pleasant party. Camille Brunelle is a nice girl that all of them mention and seem to appreciate, but none of them really knows her. Their opinion is based only on her appearance. One of them eventually says that she passed away. The characters seem confused about time: they don’t know how much time has passed, as they seem to be living in a state where the same actions are repeated, thus erasing the signs of the passage of time.

Nonetheless, the situation slowly becomes even stranger. One of the female characters says that, in fact, she did not go to the party because she went to a retirement home with her mother, who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease, where she will live the rest of her life. Then, all the characters, one after the other, reveal what they have really done that evening: robbing friends, trafficking drugs, cheating on a boyfriend, and so on. The production shows the sordid degradation of each character. One of them ends up in prison accused of robbery; another becomes a drug dealer; one of the female characters becomes a prostitute; another of the female characters works as stripper to fund her drug habit. This continues until one of the female characters commits suicide. From that precise moment, all the other characters begin to love and to imitate their dead friend: they repeat her sentences, they give a mystical interpretation to her death, and they give her a fundamental importance. Their competitive relationship is now focused on the imitation of their dead friend. At the end of the production, the actors come close to the public and again begin to speak with the audience, attempting to erase the distance between the fiction that they have just performed and daily life.

A few of the same features of young people are also shown in Cinq jours en Mars (Five days in Mars), a text by Toshiki Alya, and a production by Jérôme Wacquiez and the Compagnie des Lucioles, from Picardie, at the Espace Alya. The text presents some aspects of what has been called the “generation Y,” young people born between 1980 and 1995, who have learned to use the Internet in an innate way, because Internet was already there when they grew up. The members of this generation are very individualistic and when they become adults their situation is, for the first time in the last decades, worse than that of their parents. The first image shows, metaphorically, both the similarity and also the individualism of the people belonging to this generation. Each actor, dressed with a single vivid color, is under a giant airplane window, in which the audience can see diverse images of the landscape. With humor, in a mixture of heteroclite images with striking colors, the production shows the superficiality and the desire to have fun as a way to escape daily reality, trying to live an exceptionally exciting present that very quickly appears repetitive. The main plot of the play has also a symbolic value. It shows a young couple who lock themselves up for five days in a hotel, a “love hotel,” in the neighborhood of Shibuya, in Tokyo, to live a long sex affair without a future. They artificially create an isolated world, as Iraq war is beginning. A few other actions show symbolic anecdotes of this generation. They follow each other, as isolated instants of a present, without any apparent consequence. This creates a confusion of time among the characters of this performance, as was also the case with Cinq visage de Camille Brunelle, blurring the lines between the past and the present.

L´école des ventriloques (The School of Ventriloquists) by Jean-Michel d´Hoop, presented at la Patinoire. Photo: V. Vercheval

The most applauded puppet show and one of the most interesting productions was L´école des ventriloques (The school of ventriloquists) by Jean-Michel d´Hoop, presented at la Patinoire, (in the programme of la Manufacture). The production is based on a text, which is also a philosophical tale, written by the playwright Alexandro Jodorowsky. The main character, Céleste, falls (as if he was falling from the sky as his names suggests) in the courtyard of a very special school, a school of ventriloquists. It is a dream world that reminds us of Kafka´s world. The school is inhabited by great puppets created by Natacha Belova. These puppets are manipulated by actors (Cyril Briant, Sébastien Chollet, Pierre Jacqmin, Emmanuelle Mathieu, Fabrice Rodriguez, Anne Romain, Isabelle Wéry). In this school, the students learn to be puppeteers, and have to acquire a new identity. Each puppet represents a bold, grey, monstrous figure, in an expressionistic aesthetics. Each puppeteer is dressed in black, and he delivers the words of the puppet. They all use distorted voices, often shouting. The voices use forced clichés. They also use microphones that increase the distortion of their voices. Nonetheless, the puppeteer is also a character in himself, different from the puppet, with whom he converses. The puppet considers his puppeteer as his “servant” or as “his slave.” The puppeteer speaks in a way very close to daily life, which creates an important distortion between the puppet and the puppeteer. The relationships between the puppeteer and the puppet are very violent, and the puppets have the power. For example, the puppet of the garden, Don Crispin, speaks with Antoine his puppeteer, and both are completely different characters. In this world, taking a puppet from a puppeteer means to kill him. Céleste is forced to learn to manipulate a sordid puppet that symbolizes an instinct, an impulse or a negative feature of the human personality. And Céleste refuses and chooses positive puppets, personalizing ideals, such as a Saint able to transform reality. All the episodes are like burlesque and satiric parabolas. Céleste manipulates a big puppet, a Saint, who transforms four old and crippled blind people so that they see again. But the transformation is a failure, as the transformed puppets see with horror the reality of their companions and their own physical decrepitude, and they argue until they are sent back to their previous physical state. The extreme violence sends us back to the Grand Gignol. All these actions contain a number of Biblical allusions, treated in an irreverent way: Jesus is represented as a great and grotesque puppet beaten with a stick by his father, in a parody of Catholic religious beliefs.

A film, projected on a screen just above the stage, separates diverse sequences of the production. It shows repeatedly the disfigured face of a puppet, as if it were God or the person who put order in the world. The changes of scenery are frequent and the sequences follow each other at a very quick rhythm. Boxes used as coffins are pushed on stage and a few puppets and their puppeteers emerge from them. The production treats one of the main topics of the dramaturgy of the puppet shows: the puppeteer is nothing and he must withdraw himself from the foreground in order to let the character represented appear on stage. Then, the production, the use of the puppets and the plots are closely intertwined: the use of the puppet is justified because it helps the story acquire an obvious and striking meaning. Céleste makes three attempts to give birth to positive figures, all of which fail. The last one, when he manipulates a hero who fights against Death, ends with a new defeat. Finally, facing the director´s threats, Céleste climbs on the upper floor close to the screen that is above the stage and grasps the figure who commands the world. But it appears to be a new puppet that Céleste cannot get rid of because it represents himself, and to kill the puppet implies killing himself. He throws the puppet to the ground while he collapses, exhausted, almost without any movement.

Sic(k), a production by Alexis Armengol and the Theatre à Cru, performed at the Manufacture. Photo: Mélanie Loisel

Three other very interesting productions dealt with problems of contemporary society. Sic(k), a production by Alexis Armengol and the Theatre à Cru, performed at the Manufacture, was based on more than twenty interviews staged by the director, and on citations of diverse texts, on the topic of dependency on alcohol, drugs, or sex. The title is a play of words on the topic of the production: “sick” means to be sick, “sic” also indicates what is cited, a sentence or a paragraph, belonging to a different voice from that of the speaker.

The starting point of the production is a dialogue between two friends (Alexis Armengol and Remi Cassagé, joined later by Claudine Baschet, representing, among others, the main character´s mother). Both actors speak together in a square space, closed by plastic panels that symbolize the toilets, at the back of the empty stage. The acting tries to establish a confident relationship with the public with delivery and movements close to daily life. The main character speaks first about his alcoholic mother´s dependency. The production tackles the causes of all those consumptions, the effects during the absorption (for instance, the effect produced by acids) and the forms of dependency, the attempts to quit, the relapses, and the body´s degradation. In contrast with many discourses, the production shows the negative aspects of the dependency as well as the pleasure obtained. It treats drug consumption without any moral perspective, showing, on the contrary, the positive aspect, the feeling of well-being. The people interviewed affirm many times the desire to live as intensely as possible, to the highest limit. The production comes back very often to the 1970s to speak about freedom and sexual dependency. The dialogues try to expose the primordial and deep root of consumption.

The sequences follow each other without any interruption. They are tied by the rock music sounds of an electric guitar, played on stage by Rémi Cassabé, who then moves to the background. The music, like the speeches, is connected to the questions without answers, symbolizing what shackles the characters and what they cannot control anymore. The production utilizes microphones and audio equipment for recording, symbolizing the multiplicity of the testimonies. Actors deliver some dialogues; other dialogues are tape-recorded voices; diverse points of view are coalesced, sometimes from well-known figures such as Gilles Deleuze. Sometimes the actors speak directly to the public, and sometimes listen to the recorded voices. The production provides a multiplicity of ideas and sensations. The unusual structure based on short sequences without any plot and with characters appearing for only very short moments make all these testimonies even more striking.

Florian Pautasso’s Quatuor violence, Florian Pautasso’s Quatuor violence. Florian Pautasso, Stephanie Aflalo, Flavien Bellec and Sophie van Everdingen. Photo: courtesy of La Manufacture

Quatuor violence is an original and very interesting production written and performed by four actors (Florian Pautasso, Stephanie Aflalo, Flavien Bellec, Sophie van Everdingen), and directed by one of them, Florian Pautasso. The actors did research on violence in libraries and on the Internet. The actors create diverse forms of violence in their relationship with the public, most of the time in quite a subtle way. There are almost no violent scenes between the actors: they rarely fight or argue with each other. In one of the first sequences, an actress argues with a spectator, asking him to leave the theatre because she cannot tolerate his physical appearance, and then she gives him a panel so that he could hide himself behind it. Most of the time, it is psychological violence that is established in relation to the audience. The acting (movements and delivery) is very close to everyday life, sometimes using microphones that render the voices very soft: the pubic is approached in a way that is not surprising.

At the beginning of the production, the actors are in the foreground, and they seem to be preparing some food in an absent-minded way, like a group of friends, without paying attention to the audience who are taking their seats. Then the sequences that compose the production are based on different forms of daily violence. The four actors sit in the background and tell their stories, divided in two couples. The actors are calm: each of them speaks about an argument in the couple, from his point of view, showing partiality and dishonesty, accusing the other person of being solely responsible for their disagreement. In the following sequence, each actor narrates the diseases he has suffered from; then the mistakes he has made. The scenes between actors alternate with reading of well-known acts of public violence around the world. The actors seem to not want to demonstrate anything and to not make any statement about violence. Nonetheless, the production succeeds in making the public feel uneasy, and forces them to think about their own contradictions, and about the diverse forms of violence shown by the production.

Another brilliant production of the Avignon Fringe Festival, Occident, by Rémi de Vos, a Belgian playwright, directed by Frédéric Dussenne at Théâtre GiraSole, deals with violence in the contemporary world. The scenery is quite simple: a short stage in the form of trapezium covered with a white tiles divided diagonally by a curtain. On this minimal and impersonal stage, two actors (Valérie Bauchau and Philippe Jeusette) play a couple in their forties. The characters are anti-heroes who every evening fight with each other as soon as the husband comes back home, usually drunk. The compulsive repetition of the same action shows a perverted situation, without any possible escape. The production is divided into seven sequences: the names of the seven days of the week are projected on the screen with sunny letters. The same mechanism is repeated every evening: the man arrives drunk and insults his wife; she replies, and he names the bar where he had been, the Palace or the Flanders, and recounts something about the evening. Then the husband continues to insult his wife, and he expresses the desire to kill her.

Nonetheless, he never dares touch her, and as soon as she confronts him, he withdraws. In the isolation of the couple, a symbol of loneliness in the modern world, the same violent images come forth. If he continues to be aggressive, the woman begins to provoke him, saying that she has had sex with other men, and she insists until he collapses. He begins to cry and to say that he loves her. The man is racist, violent (when he can be), but he is cowardly, when he feels his comfort threatened. He sympathizes with Fascist movements, and he is indifferent to what happens to others. In an asphyxiating atmosphere, at the end of each argument, the man or the woman goes behind the thin curtain that symbolizes the bedroom.

In this claustrophobic space, the acting is based on the extreme and sharp precision and the quick succession of the dialogues, delivered sometimes very quickly with almost indifference. There is a highly accented rhythm, alternating moments of acceleration with sequences of slow pace, moments of violence with sequences of relief. The rhythm also creates a number of comic effects. The violence of their relationship shows the rigidity of their characters with irony and humor. The brutality is accentuated by the soundtrack: between the sequences of dialogue, the man sings very often with a microphone, as if he were in a Karaoke bar, creating a moment of strange tranquillity; but this moment appears artificial. Their relationship is a metaphor of the violence and of the selfishness of the occidental world. A moment of relief, however, is created at the end of the production. In the last sequence, the man and the woman begin to dream that they are going to travel to a hotel by the sea. In the last image, the man, with bathing suit and with a swimming cap, takes a shower on stage while his wife is watching.

Adaptations of classic plays

Oreste aime Hermione qui aime Pyrrhus qui aime Andromaque qui aime Hector qui est mort (Orestes loves Hermione, who loves Pyrrhus, who loves Andromache, who loves Hector, who is dead) an adaptation of Andromaque by Jean Racine. Photo: courtesy of Theatre du Verbe Incarné

Besides the productions of classic plays, there were a great number of adaptations in the Fringe Avignon Festival 2014. Two of them, among others, deserve a special mention. Oreste aime Hermione qui aime Pyrrhus qui aime Andromaque qui aime Hector qui est mort (Orestes loves Hermione, who loves Pyrrhus, who loves Andromache, who loves Hector, who is dead) an adaptation of Andromaque by Jean Racine and Dom Juan 0.2, adaptation of Dom Juan by Molière.

Orestes loves Hermione, who loves Pyrrhus, who loves Andromache, who loves Hector, who is dead, production by the Collective Association La Palmera, was presented at the Theatre du Verbe Incarné, at 4:00 p.m.. The success of the production is undoubtedly due to the mixture of genres. Two actors, Nelson Rafaell Madel and Paul Nguyen, dressed casually, receive the public and help them to find available seats, in a way that makes everybody think that they are part of theatre or of the company staff. They begin to chat about the Greek situation in Antiquity, that is not the situation of Greece currently, and then they speak about the Trojan War. The explanation is very simple, and there are many balloons of vivid color on the floor of the stage, as if it were a kindergarden. They narrate the story of the Trojan horse. When they mention the final killing of the inhabitants of Troy, the two actors run through the stage exploding the balloons. Then they stop speaking, and they sweep the floor. This beginning is funny and looks more like a tale for children than a production for adults. They summarize the two first acts of the play in this way, and they explain, with a very fresh style, the destiny of the women, captive and slaves of the Greek conquerors, especially the situation of Andromache, Hector´s widow. She is prisoner of Pyrrhus, Achilles´ son, who loves her. Pyrrhus separates Andromache from her son, Astyanax, and uses him as a bargain: she must accept Pyrrhus´ love if she wants to see her son. Princess Hermione is in love with Pyrrhus to whom she has been promised by her parents, but Pyrrhus does not love her. Orestes, the chief of the delegation sent by the other Greek kings, has loved Hermione since they were children, but she scorns him. The actors write the names of their characters on balloons of diverse colors and put them in buckets in a diagonal line that crosses the stage. They comment on the similarity between this situation and modern love affairs that are told in tabloids; they make a few jokes with the public, based on games of words. The lively tone used to comment on a story known by everybody in the audience (Andromaque, in the French tradition, is a text included in high-school programs, where it is frequently used as an example of Racine´s tragedy) creates a comic effect. These comments remind the audience precisely of the situation of Racine´s tragedy, while normally, the text, with its alexandrine verses, requires a high degree of attention. In this production, the public reaches the end of the second act, rested, distended by the actors´ delivery who delivers Andromaque´s speeches as if they were playing, at the limit almost parodying, like comments of a high school teenager, intercalating Racine´s text with explanations. But during the second act, they change slowly and they deliver longer fragments of Racine´s text. The transition to the tragedy is progressive. They play the third act completely in alexandrine verse: and two actors play all the female and male parts. They dress themselves in front of the public, turbans on the head to play the female characters and larger dresses to play the male. Both actors are excellent, there is a tragic tone, and the characters are astonishing. Surprised, the public look and listen with deep silence and concentration. On the empty space, almost without any object and no scenery, both actors play the end of the tragedy with simplicity and intensity.

This production was not created for the Avignon Festival 2014. It had already been performed in 2012, at the Sylvia Montfort theatre in Paris. And it is probable that it will still be on tour after its visit to Avignon Fringe Festival.

Luca Franceschi’s Dom Juan 2.0, in a production of the company Théâtre des Asphodèles. Photo: Jean Marie Refflé

Dom Juan 2.0 adaptation of Molière´s Dom Juan, in a production of the company Théâtre des Asphodèles directed by Luca Franceschi, presented at 11:00 a.m. at the Théâtre du Roi René, is very interesting for a few reasons.

At the beginning of the production the actors argue on stage, and it is not a clear beginning. An actor explains that they are at the end of an artistic residence, and that there are many things that are not ready yet: they will only play a few parts of the play. During the production, an actor indicates a few times that there is a problem, and that they are trying to find the right solution; the actors are also very often at the edge of the scene, and they comment on or criticize what the others do. For instance, at the very beginning of the production, the actor who says the prologue is interrupted by two actors who begin to play. He protests with angry gestures, then joins the group of actors who are seated, and finally he ends interrupting the action. So the acting very often directs the attention to the acting itself, creating a “mise en abîme.” The actors, at the edge of the scenery, dress themselves and eat, while the public is watching them. The production then has two levels: the fiction represented and the actors´ group who parody the play, introducing many comic moments, addressed directly to the public.

The other interesting aspect is the use of the Commedia dell´arte, with typical actions and with a great variety of lazzis, mixed with other ways of acting. This mixture is very dynamic. It is a speciality of this group: they also present an ever more successful production at the Avignon Fringe Festival, in which they mix Commedia dell´arte, hip-hop, and break-dance. The actors do not play with masks, as is usual in the Commedia dell´arte. Nonetheless, the self-parody means that the caricatures and the cliché on which the production is based, are never stressed, and the acting preserves its dynamism. The acting is outstanding, imaginative, and quick, with many variations, slowed down movements, and a few brief tableau vivant. For instance, the statue of the commander who has been killed by Dom Juan and whose grave he goes to visit, is represented by five immobile actors around the metallic structure of the scenery, after an actor has just told the public that they have not been able to find a good solution to representation of the Commander´s statue.

Luca Franceschi’s Dom Juan 2.0, in a production of the company Théâtre des Asphodèles. Photo: Jean Marie Refflé

The scenery also helps the adaptation of the play: it has a metallic footbridge with tree stairways that give access to the upper level. The scenery reminds us of the simple stages probably used by Molière at the beginning of his career, but it also evokes the constructivist structures. It probably also has a practical reason: to be taken down very quickly in order to free the stage for the next company that plays in the following time slot (in fact, in the performance I saw, the actors began to take down the scenery, immediately after the applause, while the public was still leaving the theatre). The actors climb and use the footbridge as a useful structure for acting. The costumes are very casual too, evoking a rather modern vague epoch.

The rhythm of the succession of sequences is very good until the end of the production. Nonetheless, all the tragic aspects of the play are dominated by the lightness of the acting that removes all the gravity from Molière´s play.

Gérard Gelas’s Le Nouveau Tartuffe, by Jean-Pierre Pelaez, at Théâtre du Chêne noir. Photo: Sergine Robert

Some classics are adapted to other styles. An example of adaptation of a classic to the Théâtre de Boulevard style is Le Nouveau Tartuffe by Jean-Pierre Pelaez, an adaptation of the Molière´s play Tartuffe. This adaptation had a great public success.

Le Tartuffe Nouveau, production directed by Gérard Gelas, has been presented at 3:30 p.m. at Théâtre du Chêne noir. Starting with Molière text, the adaptation conserves important parts in verse, and mixes them with modern clichés, used as comic elements, taking away all depth from Molière´s play, that is transformed into a big farce. Dorine becomes Consuelo, a very slim and alert Colombian maid that smokes hashish and speaks Spanish. Tartuffe has a German name, Kruger; but the most important cliché is that the devotion from the original Tartuffe is replaced by the humanitarian action, to help the homeless people and the destitute. Kruger uses modern tools, the television and the media, and when the acting begins, Kruger is preparing an important television broadcast about misery. He wants Marianne, with whom he would like to be married (he is already the lover of Orgon´s wife, his host), to become his assistant in his Association. Marianne´s fiancé is called Patrice and has just succeeded in becoming captain of the police: he will be the person who will finally arrest Kruger. There is also a mixture of epochs: while all the characters are dressed with costumes that evoke the seventeenth century, Kruger wears a white contemporary suit and a white scarf; Patrice appears dressed as a revolutionary leader of the French revolution when he arrests Tartuffe in the name of the Republic. The production has the clichés, the qualities and the limits of the theatre of the Boulevard. The acting is full of comic gestures and of stressed movements of nodding reference in the direction of the public, who roar with laughter throughout the production. As a farce and a modern adaptation in the last scene, Kruger get rids of the handcuffs and escapes while the other characters are throwing a party.

Established directors

There are also in the Avignon Fringe Festival artists who have been in charge of public theatres, but once the limit of age to direct any official structure in France is reached, continue their careers in private companies, as for example in the Avignon Fringe Festival 2014, Daniel Mesguich and Jean Claude Penchenat.

Daniel Mesguich’s Trahisons (Betrayals), by Harold Pinter, at the Théâtre du Chêne Noir. Photo: Chantal Palazon

Trahisons (Betrayals) by Harold Pinter, production directed by Daniel Mesguich, was presented at the Théâtre du Chêne Noir, at 6:15 p.m.. A woman, Emma (played by Sterenn Guirriec) has a lover, Jerry (played by Eric Verdin), who is the best friend of the husband (played by Daniel Mesguich). A fourth actor, Alexandre Rudy, plays a waiter who serves the characters when they sit down at a table in a cafe or in a restaurant, but who also moves elements of the scenery in many scenes. The play runs backward in time, presenting the episodes following an inverse chronological order, showing lies, betrayals and dissimulation between the three characters.

Daniel Mesguich adds a few characteristic features of his poetics as director to this story of revelation of the duplicity—and his deconstruction in the development of the production. The most surprising aspect is undoubtedly the visual metaphors of the character´s subconscious or of his hidden thoughts. The music and the noises of the soundtrack also intervene to symbolize the irruption of the disturbing memories. Very often a character, absent in a scene, is present on stage, beside or behind the character who is speaking, as a visualization of his thoughts or memories, like remorse or mental presences he cannot get rid of. The more a character is tormented by his thoughts, the more these “absent” presences are visualized. Very often the successive scenes are intricately tied by the presence of a character, who was in the previous scene but who is not supposed to be in the current one, as an uncontrolled memory of the subconscious of the character. The superposition of levels, as several layers of time, increases throughout the production until the last scene. In this scene, Jerry declares his love to Emma in the newly-wed’s room, where all the furniture is upside down as an image of the emotional and sentimental turmoil that the scene implies for the characters.

Productions from other countries

Belgian productions, coming mainly from Wallonia and from Brussels, and the productions coming from Switzerland were the most numerous among the productions coming from other countries. For example, the Théâtre des Doms, which always shows Belgian productions, had nine productions in the 2014 Avignon fringe Festival; the association “la charge du rhinoceros” (the charge of the rhinoceros) based at Brussels (which support Belgian and African productions), co-produced “Occident,” which was presented this year in Avignon (see above). But one could see productions of many other countries in the Avignon Festival. For example, the Théâtre de la Condition des Soies this year presented four productions of dance, of music and of acrobatics (mixed with elements of other genres) coming from Taiwan; la Manufacture this year presented a special program with Quebequois productions, a “focus Québec” with three productions (see above); at the Théâtre de l´Albatros, at 6:15 p.m., a group of five Greek actors directed by Tilemachos Moudatsakis, represented with great intensity The Perses by Aeschylus, in Greek with surtitles, with an aesthetics of music and movement and with many tableau vivants; at the Cour du Barouf, there were a few productions of Commedia dell´Arte, two of them Italian. There were twenty-six different countries present in Avignon Fringe Festival 2014, but in the overall number of productions, those from other countries were widely a minority.

Other cultural activities

But in the Avignon Fringe Festival there are not only performances of theatrical productions but also a large number of other cultural activities, such as meetings, lectures, workshops, concerts, debates, round tables, expositions, installations, productions that are lessons, and master classes. Most of these activities are open to everyone wants to attend. Most of the meetings concern the professionals of the theatre companies who participate in the Avignon Fringe Festivals. The problems that are touched upon concern diverse aspects of theatrical professional activity: juridical, artistic aspects, but mainly problems of professional production, diffusion, and the creation of networks for the diffusion. These meetings are the occasion for discussions and public debates. Among these, for example in 2014, a few debates took place about puppets and their function in the current artistic world (debates on the 11th of July at 3:30 p.m. at the Village du Off, 12th of July at 4:00 p.m. at the Caserne des Pompiers—a former fire station transformed into a theatre). These debates underlined the increasing presence of puppets in the theatre (in Avignon there were thirty productions) and mainly greater visibility, the increasing mixture with other arts, the debate on the traditional or the modern puppet, and the need—mainly the desire—for a dramaturgy specific to the puppets. But on this last and fundamental point, the debate concluded on the remark that little has been done. Many debates took place on various topics, such as the place of Shakespeare in the Festival (Maison Jean Vilar, Sunday the 13th of July, at 5:30 p.m.), the relationships of production and diffusion among European countries (Saturday the 19th of July and Sunday the 20th of July at the Village du Off).

The situation of the “intermittents du spectacle” (the workers of the entertainment industry without steady employment, who work only a part of the year—not twelve months) has again been a central issue this year. A special Social security system allows the workers of the entertainment industry once they have worked a certain number of hours per year, to benefit from a especial unemployment insurance during the months they do not work. This allows an important number of these professional to pursue their career all year without being forced to have another job. The economic crises and the economic adjustments that it is supposed to imply, result that this system has been questioned for many years. It is considered, depending of the point of view, as a privileged system compared to those of other workers or as a necessary condition for the development of an artistic profession. A new law that increases the cost for the employers and that requires other conditions for the workers, that makes it more difficult to access unemployment insurance, has been approved during the spring of 2014 and has been brought into effect during 2014. The workers of the entertainment industry threatened to paralyze the festival: finally almost nothing happened in the Fringe Festival. All theatrical groups gave their support and their solidarity to the “intermittents,” and all the productions ended, after the applause, by a call to support them; but the movement in general has been scarcely followed, and the Fringe Festival knew no interruption. Even on July 12th, a day of strike at a national level, most of the theatres of the Fringe Festival opened.

There has been a general evolution in the Avignon Fringe Festival; it seems more diverse every year. If most of the productions are theatrical, the number of puppets, circus, and dance productions is increasing every year. The Organization of the Avignon Fringe Festival want to strengthen certain structures that were created last year, such as the Web Television, a television team that makes reports, broadcasts, some that record live lectures in the Fringe Festival and puts them on line; or the publication of the “Fringe editions” (“Les Éditions du Off”), that collaborate with the Librairie Théâtrale—a Parisian theatrical edition—published five plays performed in the Fringe Festival last year. For next year, the organizers of the Fringe festival want to strengthen the sale of the tickets online of as many productions as possible, a service that would be free for the companies that will come to the Avignon Fringe Festival of 2015.

is Senior Lecturer in French Literature at the University of Santiago de Compostela. He wrote his Ph.D. in Drama Studies at University Paris 8. His research interests are time and rhythm in theatrical productions/performances and in dramatic texts, the French contemporary theatre – especially the productions of the Theatre du Radeau – and the Canadian theatre.

European Stages, vol. 3, no. 1 (Fall 2014)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

• The 68th Avignon Festival 2014, July 4 to 27: Protests and Performances by Philippa Wehle

• The Avignon Fringe Festival 2014 by Manuel García Martinez

• The Reality Bites of New Bulgarian Theatre by Dessy Gavroliva

• Happy Days: Enniskillen International Beckett Festival 2014, July 31-August 11 by Beate Hein Bennett

• Flemish Theatrical Exceptionalism Mostly Glimmers, Sometimes Wavers by David Willinger

• Shouting at the Devil (and Everyone Else): Yaël Farber’s Production of The Crucible at The Old Vic by Erik Abbott

• Mladinsko Theatre and Oliver Frljić’s Damned Be the Traitor of His Homeland! (Sibiu International Theatre Festival, Romania, 2014) by Ilinca Todoruţ

• Barcelona Theatre (2013): Responding to Spain’s Crisis by Maria Delgado

• Report from Madrid by Duncan Wheeler

• Irish Colonial History on the Hungarian Stage by Mária Kurdi

• Fantastic Realities: Actors as Puppets and Puppets as Actors by Roy Kift

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2014 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016