2013 was a year of protests in Bulgaria. The cold, dark, early days of the year brought about what was later called “hunger revolts” and “electricity bills revolts:” people went out on the streets because they could not afford to pay for their bills any more. The beautiful seaside capital of Varna became the epicenter of the protests—angry masses that could hardly articulate a project for a better future, were shouting with their bodies: “we cannot live like this anymore,” On February 20 in Varna, a young man—an active and vocal protestor against the government and the local business conglomerate—set himself on fire. Plamen, whose name in Bulgarian means “flame,” died of his injuries ten days later, to sadly earn himself comparisons with Jan Palach from the former Czechoslovakia and Mohamed Bouazizi of the Arab spring. More self-immolations followed across the country, the social revolt continued, and in March the government fell.

The new government very soon caused another type of outrage with its move to appoint the business media mogul, commonly perceived as the embodiment of corruption, as the chief of counter intelligence. The protests that broke out in June persisted until the end of the year, and every day there were between three to fifty-thousand people on the streets. Months after the last protestors returned home, this government fell as well, not because the protests, but as a result of internal struggles and corruption.

Twenty five years after the end of Communism, Bulgarians got everything they wanted—freedom of speech, of political activity, of movement, and of business initiative. But they were discontented with the fact that all these freedoms brought along with them social inequality, poverty, failing judiciary system, and a feeling that injustice rules the country. Massive emigration created distorted families and the “Skype mothers” (a phenomenon known when the parents go abroad to earn the living and communicate with their children via Skype.) Confronted with such a reality the Bulgarians were not coping any more.

Sometime around that turbulent time, a Bulgarian theatre director returned to her country after a study in Finland to create her own company and gradually define a new artistic path, previously unknown to the theatre scene there. Neda Sokolovska was first trained as an actor in the Bulgarian Theatre Academy, which religiously taught the Stanislavsky method. By the end of her study, she had mastered her emotional memory, knew how to produce affecting and believable emotions onstage, and was eager to learn more. At that point she discovered Helsinki Theatre training, where teachers cared little about Stanislavsky and his system. Post-modernism was the religion there, and students were encouraged to learn about new approaches, experiments, and finding their own voice in the theatre. Such theatre fascinated Sokolovska; she did her best to learn about its traditions, mastered new techniques and contemporary trends.

Her first work back in Bulgaria, Invisible 1, was a documentary performance introducing us to the life of handicapped people, and to the new aesthetics in the Bulgarian theatre. Out were the heavy sets, costumes and make-up; in was authenticity, staying true to the voices whose stories knitted the delicate web of the dramaturgical text; out were the big stages of nineteenth century theatres, distancing and respecting the spectator; in was the intimate close-up relationship with the audience. Vox Populi was the name Sokolovska gave to her theatre company, the voice of the people. And her group indeed carefully listened to the voices of the people they interviewed, reproducing them religiously word-by-word on stage. Already the second production of the company, Yatse Forkash, brought Neda Sokolovska a wide recognition. The performance told the story of God-forsaken inhabitants of rural Rodopi mountain villages and delved into their perceptions of authentic folklore, collective memory, rural life, and the relationship of modernity to tradition. It was a journey beyond the clichés about the idyllic traditional life, far away from the noise of twenty-first century civilization. It was rather an intimate encounter with the roughness of human existence in remote Bulgarian mountain regions. The performance was awarded the highest theatre prize in Bulgaria for its dramaturgical text, and other awards followed, only to show what quick and easy welcome both the audience and the critics offered to the newly emerged documentary theatre in Bulgaria.

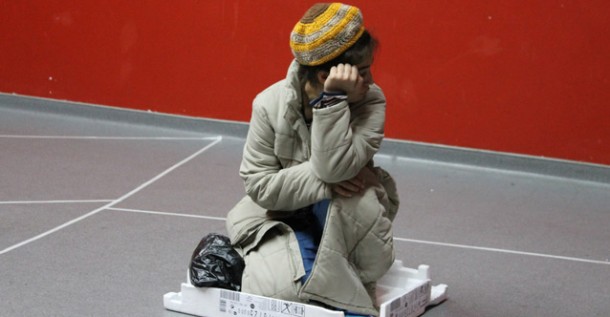

Another project, Home, received the best performance award at the Bulgarian New Drama Festival. Home addresses a social problem that Bulgarians encountered only after the fall of communism: homelessness. Only fifteen years ago, a picture of people digging in the rubbish containers and sleeping in parks and courtyards was shocking for most Bulgarians. Now, it is not shocking any more; it is a part of everyday city life. Sokolovska and her excellent actors made us stop and hear the voices of those who have fallen, and realize that these are people like us, that in the modern world everyone is vulnerable. They make us feel empathy, and invoke in us a willingness to act to overcome the dire social problem. The dramaturgy of the performance is based on homeless people’s stories, which accumulate to build an emotive response to their problems. We are mercilessly shown how people left by their relatives and partners, with no job, with drinking or psychological problems have nowhere to go in today’s Bulgaria, but the street. The social security mechanisms that communities traditionally provided have long vanished, the social support that communist Bulgaria offered was thrown out together with totalitarianism and ideological control. Instead, we have an inhumane society lacking both the institutions, the human empathy, and networks of support that could help the fallen. But what is deeply moving is that this performance succeeds in making us see the human in every homeless person’s story. It makes us understand, sympathize with, and even love the poor people that we usually try not to notice when passing by them on the streets. It makes us realize that—put in an extreme situation as they are—people learn to recognize the value of life, of friendship, and of trust. And to realize that often, these are better people than us. After seeing the show, my 12-year old daughter confessed that the performance instigated in her a desire to speak to the homeless people whom she previously childishly feared. If one wants to find a social impact of art, here is one of its powerful manifestations, I thought.

Protest.mp3 was the title of one of the performances of Vox Populi, which was produced in the midst of the rebellious 2013. Every presentation of the show turned out to be different, because it had to incorporate the newest swings of the protesting streets. One year after its opening night, after two governments’ resignations, and dozens of self-ignitions, the performance is still a work in progress. As is, by the way, our confused contemporary Bulgarian reality.

The performances of Vox Populi are rather simple in their theatrical language. Authenticity, respect for the sources that make up the dramaturgy, and the actors’ talent and engagement are at the center. This theatre works both as an amplifier—because it makes us hear the unheard voices next to us, and as a diminisher—because it makes the stories it tells sound intimate, as if shared with the audience in a whisper.

When Neda Sokolovska was making her transit from Finland to Sofia, another theatre director fascinated with contemporary documentary stories made a similar transition. Georg Genoux, a Hamburg-born German, who in the early 2000’s went to study theatre in Moscow, and stayed there for more than a decade, moved to Sofia as well. In Moscow he was one of the first collaborators of the Teatr.doc collective. He worked with the Teatr.doc founders on masterpieces like One Hour and Eighteen Minutes, and staged there performances like Democracy.doc. Still in Moscow, Genoux established his Joseph Beuys Theatre Company and was a part of a very impressive and productive group determined to create a space for understanding and appreciation of documentary theatre in Moscow. Already there Genoux and his Joseph Beuys Theatre company, along with the artists working in Teatr.doc, received wide applause and won many prizes. In the decade since 2002, when Teatr.doc was established, documentary made its way in one of the most traditional and conservative theatrical scenes in Europe, the Russian one.

And here Georg Genoux comes to Sofia, with his decade-long Moscow Theatre presence just behind him, and fascinates a bunch of young and talented actors with his vision for the new and important documentary genre. In Bulgaria today young and talented actors often lack artistic opportunities and therefore they devote themselves to documentary theatre. For instance, Replica Theatre (with which Genoux collaborated) first turned to contemporary dramatic texts such as Truth Beyond the Polar Circle by Yuriy Klavdiev and A Couple of Poor, Polish-Speaking Romanians by Dorota Masłowska, only to later focus on field research that resulted in documentary performances like We Are the Rubbish of Eastern Europe. Theatre Replica actors describe their activity as a socio-political dissection of contemporary life. This Theatre makes us turn to the world in which we live and ponder about the contemporary human condition. Its performances are intimate, sharp, merciless, and political; its actors are socially and politically involved, and their talent makes their engagement contagious.

With his theatre-making history, knowledge and contacts, coming to a theatrical environment that was just starting to experience the varieties of documentary theatre work, Georg Genoux felt a compulsion to share his experience. His work in Sofia and especially in The Red House Center for Culture and Debate, a group that hosted the birth of documentary theatre in Bulgaria, went beyond theatre performances. It encompassed documentary theatre showcases, documentary drama writing workshops, lectures, and public discussions . . . a whole complex educational effort, or shall we say, “seeding, watering and gardening” of a new art form.

And yet, at the same time, there were other theatre groups intuitively turning to documentary techniques—without much exposure to international examples, without any theoretical background or training (apart from what they could self-teach themselves). One such group is tellingly called After a Real Case, and it uses its members’ experiences, memories, and reflections to create their theatre. One of the exemplary performances of the group’s founders, Irina Goleva and Ognyan Golev, is Ostalgia, where they rework the experiences and memories from their childhood in communist Bulgaria. The Golevs state: “Where people do not talk about the past, it seems that the past does not exist,” and they ask: “How does this artificial amnesia shape the relations between generations? Why the Change we dreamt about is not happening, when we are already free? What do we have to do so that we are happy where we are born, given the fight for survival that we are forced into? Why do we need to pray to non-existent gods like the energy-providers?” Two months after the premiere, in November 2012, people swept out the streets in Varna, motivated by the same questions, shouting almost literally the same words.

The desire to dissect contemporary reality, to put on the table painful social and political issues, compelled the documentary theatre makers to go beyond pure theatrical form and seek direct engagement and dialogue with the audience. Neda Sokolovska decided to regularly hold audience discussion immediately after her performances, and Georg Genoux, together with the The Red House, organized debates on the issues that his performances raised. It is not a coincidence that for the first two years more than ten documentary theatre performances were presented by The Red House Center in Sofia. Since it was established in 2001, this independent cultural venue became “the place” for independent performing arts work and innovation; it was also the first to regularly organize public debates on important social, political, cultural and economic issues of the day. The Red House, in fact, introduced to the Bulgarian cultural landscape open, interactive, and enlightening citizens’ debates, and throughout the years it has remained the trendsetter in the field. In The Red House, the documentary theatre artists found their accepting home, a sensitive audience, and a stimulating intellectual environment.

But it is interesting why this kind of theatre received such a unanimous welcome in Bulgaria from the theatrical and artistic community, and the public at large. One can safely guess that in the complex globalized world, penetrated by contradictions, people find it hard to make sense of their lives. In a public space dominated by the noise of yellow press, over-flooded by details of endless political struggle, corruption scandals, and drastic examples of injustice, documentary theatre turned out to be in demand because it gives voice to marginalized stories that otherwise would be lost. And without these stories, we cannot make sense of the distorted bits of reality that do not come together any more. Most importantly, this kind of theatre makes us see and listen to the people next to us; thus re-establishing the broken social web, and making us regain the feeling that we are part of a community of shared stories, rather than anonymous elements lost in an incomprehensible world.

is founder and chairwoman of The Red House Center for Culture and Debate in Sofia, Bulgaria—a non-governmental cultural center that brings together contemporary art and civic debate on political and social issues. In 2011, she convened for the first time the Network of European Houses for Debate “Time to Talk,” and currently coordinates the activities of the Network. Previously Gavrilova was Director of the Center for Arts and Culture of the Central European University in Budapest (2005-2010) and a founding manager (1997-2000) of the Performing Arts Network Program for Central and Eastern Europe of the Open Society Institute.

European Stages, vol. 3, no. 1 (Fall 2014)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

• The 68th Avignon Festival 2014, July 4 to 27: Protests and Performances by Philippa Wehle

• The Avignon Fringe Festival 2014 by Manuel García Martinez

• The Reality Bites of New Bulgarian Theatre by Dessy Gavroliva

• Happy Days: Enniskillen International Beckett Festival 2014, July 31-August 11 by Beate Hein Bennett

• Flemish Theatrical Exceptionalism Mostly Glimmers, Sometimes Wavers by David Willinger

• Shouting at the Devil (and Everyone Else): Yaël Farber’s Production of The Crucible at The Old Vic by Erik Abbott

• Mladinsko Theatre and Oliver Frljić’s Damned Be the Traitor of His Homeland! (Sibiu International Theatre Festival, Romania, 2014) by Ilinca Todoruţ

• Barcelona Theatre (2013): Responding to Spain’s Crisis by Maria Delgado

• Report from Madrid by Duncan Wheeler

• Irish Colonial History on the Hungarian Stage by Mária Kurdi

• Fantastic Realities: Actors as Puppets and Puppets as Actors by Roy Kift

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2014 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016