Many theatre festivals in Germany make headlines in the national and international press. The biennial Augenblick mal! (a rough translation might be “Just a moment!”), whose program this year not only featured top German productions but also workshops, seminars and other artistic gatherings as well as two international guest performances from France, is sadly not one of these. The reason is simple. It’s a festival of theatre for children and young people. Just a moment! Don’t skip on to the adult plays in this review but take the time to read more about four truly remarkable shows, some of which would put adult theatre to shame. Theatre for Young People (TYP for short) in Germany has long since left the realm of fairy tales and freckled youngsters larking about in harmless comedies. Quite the contrary, the range of shows during the festival covered a huge amount of socially and politically explosive themes not only in the form of spoken drama.

For example, Flight of Fancy, or Why Cry? (for eight to eleven-year-olds), was a one-hour dance show. At the start of the performance we see four clearly demarcated spotlit circles on a bare stage. A disembodied voice calls out an order: “Fit in and don’t make such a fuss!” And on command the four dancers (two men, two women) slip into their individual worlds and the roles adults expect of them. Which of them can be cleverer, quicker, more attractive, best behaved? Contrasting with adults’ desires to harness children into the competitive world of “success” and “failure” are the children’s natural spontaneity and creativity. What’s wrong with showing your emotions, turning ink blots into octopuses, running around, being ridiculous and making a noise? Do children’s lives always have to conform to adult wishes? Does everything have to be down-to-earth and organized? Or is it possible—even preferable for a child—to soar through the air as these dancers do in flights of fancy? Even at the risk of falling on your face? This brilliantly conceived show throws up the questions in an ever-changing sequence of serious and humorous situations. But the choreographer Beate Höhn, from co>labs in Nuremberg, does not restrict herself to pure dance. Instead, she introduces trampolines, drawings projected onto overhead transparencies, a flying fish, and oversized clothes that the children are forced to wear and which restrict their movements (a wonderful metaphor for the problems shown here), from which they liberate themselves by dancing around inside them and turning them into surreal shapes. The show ends with a visual plea to both children and adults to take things a little more easily. Life needs order and discipline but a life without fantasy and the freedom to create new worlds is only a half a life.

“If dealing with your own life is a problem, how much more difficult is it to save the world?”

This is the question asked by a fast moving comic show called Trashedy (ages eleven and up), presented by Performing Group under the direction of Leandro Kees, who also played one of the two roles alongside Daniel Mathéus. The first thing we see onstage is a series of animated projections of someone drawing cartoons. This defines the approach to be taken: for animated cartoons go on to play a major role in explaining such global problems as pollution, unrestricted consumerism, and exploitation. But do not underestimate the achievement of the two actors, whose brilliant clowning, juggling and lunatic dance numbers are combined with quick-fire dialogue and a crazy quiz show. Light and sound also play a major role in this prodigiously detailed rundown of a complex subject. This is one of those shows which are simultaneously highly entertaining, highly instructive, highly political, and deeply human. Not for nothing is this prize-winning production being quickly booked by venues throughout Germany and abroad. They even have an English-language version.

If you think global problems are an unsuitable subject for children’s theatre, then what about homosexuality in football? Stand Your Ground (age thirteen upwards), presented by the “boat people projekt”—a fringe theatre group from Göttingen whose main areas of interest are refugees, migration, and movements on the fringes of society—is a solo show featuring a football fan, Matthias, in the changing room of a stadium. The audience/fans are sitting on benches to the left and right of a small area covered in artificial grass. At the start of the show some of them are given football shirts and sworn in as fans. Matthias confronts them with a statistic: if ten percent of all men are homosexual, there must be around 500,000 gay men active in German football. Who are they, asks Matthias, and where are they? How do we recognize them? By their deodorants, their fashionable hairdos, or even by the pink football boots that seemed to be the current favourites amongst many major stars? And what about all that heavy body contact during the game? There are claims that the “hardest” players are the closeted gays who are trying to assert their masculinity. Then again, is the mass hugging and kissing to celebrate a goal purely a ritual or does it conceal some deeper erotic overtones? If so, asks Matthias, so what? The play, which includes documentary film excerpts with football fans, ends when Matthias holds up a folded piece of notepaper which he claims contains the name of a gay footballer currently playing in the German national team. As he leaves, he places it on a stool in the middle of the audience. It is a tribute to the show that at the performance I saw no one was interested in looking inside. This educationally enlightening and socially courageous piece of work has already been invited by several professional football clubs to be shown to its fans. The wider the audience, the better.

One of the notable features about this year’s festival was the high proportion of so-called “projects” to scripted theatre plays, and when I first saw the program, I was more than disturbed to see how few dramatists’ texts were amongst the selected shows. The trend in adult theatre in Germany is now being clearly reflected in TYP. It was all the more gratifying, therefore, for me to confirm that the most impressive production of the many I saw was indeed a written play. David Paquet is a young Canadian playwright based in Montréal who writes in French. His play 2.14. AM/FM (14 years upwards) is by far the best of the plethora of theatre pieces I have seen to date that deal with students who run amok on killing sprees in schools. Like Stand Your Ground, this highly impressive prize-winning production from the Theater der Jungen Welt in Leipzig also featured a stage area running downwards like a broad ramp between two sides of the audience; another creative visual metaphor, since all the characters seem to be on the slide. Indeed some of the situations border on the surreal. There is a girl who eats worms to try to lose weight, and a teenage boy who falls in love with a seventy-seven year-old woman with an addiction for vodka. The teacher feels so uncomfortable with his life that he has a constant taste of sand in his mouth. All of them are faced with the question of what to do with (the rest of) their lives. From the outset, the audience can guess how the play will end because the stage is marked by silhouettes of bodies lying on the floor as in a crime scene. Thus, from the very start, the grotesquely humorous accounts of uncertainty and inadequacies are imbued with a tragic end, even though it is difficult to guess who the killer might be. David Paquet intensifies this even further by inviting us to empathise with all the characters, who are impeccably portrayed by a very talented ensemble under the direction of Ronny Jakubaschk. Book your seats for the next edition of Augenblick mal! in Berlin in spring 2017.

Staying with Franco-Canadian playwrights for a moment, one of this century’s outstanding and most relevant plays has to be Scorched (original title Incendies) by Wajdi Mouawad, first produced in Quebec in 2003. The play begins in a lawyer’s office in an unspecified Western city where the siblings Janine and Simon have been summoned to hear the last will and testament of their mother, Nawal, to whom they have not spoken a word during the final five years of her life. In her will Nawal says that she will only be able to rest in peace after the two have delivered letters to the brother they did not know they had, and the father they thought was dead. Reluctantly, they set out on a journey to the Middle East in search of their entangled roots. A flashback takes us to an unknown country in the Middle East, probably Lebanon—the playwright was born in Beirut—but the precise setting could be anywhere where civil war is raging. Here we meet Nawal as a pregnant unmarried teenager in a peasant village who, despite her loving relationship with the father of the child, is forced to surrender her baby who is then taken to an unknown destination. Undeterred, Nawal sets out to find her lost son. Her journey takes her through a land torn by civil strife, appalling violence, and mindless revenge including a horrific explosion that rips through a bus sending all its inhabitants up in flames. Nawal gets so entangled in the horror that she too turns to violence and is imprisoned in a filthy cell for a military assassination. Subsequently, she is tortured and raped by a young psychopathic killer. Scorched is a modern Oedipal tragedy about revenge and reconciliation, identity and cultural heritage, loss and redemption that tells us more about the contemporary world than a thousand trendy plays—mostly comedies—about domestic relationships in modern Western society.

I was lucky enough to see a production in the Grillo Theater in Essen where the director, Martin Schulze, elected to dispense with naturalistic settings in favour of a large white room in which a war crimes tribunal had gathered. Thus the actors were able to step out in turn to take on the roles of the characters involved without resorting to “blacking up” to indicate that they were somewhere in the Middle East. This decision had the advantage of allowing us to place the situation in any country in the world suffering the ravages of civil war. Inspired by a text that was simultaneously realistic and poetic the first-rate ensemble in Essen presented its audience with a heartrending story with a final revelation that left us as speechless as Nawal herself had been during her final five years. For anyone who is now thinking that the theme seems somehow familiar, the play was turned into an equally magnificent film in 2011, entitled Incendies (The Woman who Sings), that was subsequently nominated for an Oscar for the best foreign film.

From time to time there comes along a production that stops the heart and convinces you that theatre is the deepest and finest of all the living arts. Such a show was presented to us at this year’s annual Festival in Recklinghausen whose theme was France. At first sight it might seem that a Greek play, Antigone, by Sophocles, in a new English-language version by the American poet Anne Carson and directed by the Flemish director Ivo van Hove, would sit ill amongst such Gallic companions as a farce by Eugène Labiche, Molière’s The Hypochondriac and Ionesco’s Rhinoceros. But here the play’s female protagonist is none other than the Oscar winner, French actress Juliette Binoche. The play opens with Antigone dressed in black standing alone on a bare stage before a projection of a windswept desert landscape in the midst of which is a gaping hole that in turn becomes a moon and a sun. In front of this deceptively simple background (set and lighting by Jan Versweyveld) and a few steps below is a bureaucratic office cum library, full of books and a large leather sofa that serves as Kreon’s headquarters. Thus at the start we are faced with the contrast of the emotional winds of fortune that can blow in any direction, and the unfeeling, enclosed atmosphere of state reason. This is emphasised in the very first scene between Antigone and her sister Ismene. Whereas Ismene refuses to take her sister’s side on the grounds that her action is not only mindlessly futile but also crosses the line of law, Antigone insists that “my dead are mine / and yours as well as mine / do what you like /but I will not betray him.” The scene is now set for a confrontation between two different worlds that can only end in disaster. For when Kreon appears, he is dressed more like a contemporary entrepreneur than an ancient ruler. Indeed his whole aura is one of power underpinned by logical calculation rather than tyrannical ravings. This dictator is quietly intelligent, a factor that makes him all the more dangerous in Patrick O’Kane’s brilliantly outlined and deeply felt interpretation. For it is only when conflicts come to a climax that he breaks into clamorous bouts of frustrated fury that will brook no opposition. At the end of the play when faced with the lethal consequences of his actions this Kreon is a broken man, more to be pitied than condemned. Indeed in this production and with this performance the play could also be called the tragedy of Kreon.

Juliette Binoche and Samuel Edward-Cook in Antigone directed by Ivo van Hove. Photo credit: Jan Versweyveld.

All this is not to belittle the immensely emotional and brilliantly theatrical interpretation of Antigone by Juliette Binoche who played the role, not only in immaculate English but also with impeccable clarity. In the central scene where she kneels before the corpse of her dead brother and embalms it with oil before smearing it with earth, her actions are so simple that they become heartbreaking. And when in the end she lies dead on the stage before a huge projection of herself, her corpse only illuminated by a gigantic white hole (the moon/sun) above her belly, it seems as if she has indeed been disembowelled. Binoche and O’Kane might easily have stolen the show as the undoubted stars they are. Instead they fit seamlessly into a universally powerful ensemble of actors from the fearful guard played by Obi Abili, to the helplessly conformist Ismene (Kirsty Bushell), the determined and reluctantly oppositional Haimon (Samuel Edward-Cook), the desperate Euridike (Kathryn Pogson), and the fiercely fearless and condemnatory blind Tiresias (Finbar Lynch). Finally, Anne Carson’s new version is a miracle of contemporary verse that not only seems to mirror Sophocles original text as far as this is possible, but brings it brilliantly up-to-date so that at no time are we aware that this is just another English version of a dusty old classic. Indeed the final image in this production is of the broken Kreon slumped in his sofa against a silent background video projection of people going about their daily activities in a twenty-first century nocturnal urban landscape dominated by tall anonymous office blocks. Quite simply this is a show not to be missed, especially for anyone who tends to think that Greek classical drama is simply a succession of endless rhetorical monologues.

Returning to present-day France, this year’s Recklinghausen festival presented us with no less than three contemporary dramatists, two of whom I was encountering for the first time. Joël Pommerat (born 1963) is a self-styled author-director who tends to develop his plays with his own ensemble. In this he has clearly been successful because in the course of his career he has scooped a number of notable awards including on several occasions the Prix Molière. His plays are deeply anchored in modern life and he regards the theatre as “a place in which to interrogate and experience humanity.” The Reunification of the Two Koreas premiered at the Odéon theatre in Paris in 2013 and was promptly overwhelmed with awards. The Intendant of the State Theatre in Frankfurt (and future Intendant of the Berliner Ensemble), Oliver Rees, was present at the premiere and promptly decided to buy the rights for the first production in Germany. Two Koreas has nothing to do with the country of the same name: it is simply a metaphor for the difficulty that individuals have in finding harmony and love for one another. The play consists of around twenty unrelated scenes for twenty-four women, twenty-seven men and a singer who performs in French between the scenes. Some people have compared it to Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde, but Pommerat’s play is anything but a series of successive sexual encounters. The first scene for example is nothing more than a dialogue between a middle-aged woman and an offstage interrogatory voice wanting to know why the woman is seeking a divorce. The answer is simple and direct: “There is no love between us. And never has been.” Listening to the exchange it is eminently clear that this scene has been developed from an improvisation. On the one hand this gives it a straightforward simplicity, but on the other hand by the end of the scene (“I don’t have a choice. You know what I mean?” “Yes, I think so”) it borders on banality. In Rees’s production, all the scenes are played in a uniformly anonymous setting that could be anywhere between a railway station, a hotel corridor, a waiting room, a domestic lounge or a warehouse. The interchangeability of the set also reflects the interchangeability of all the various relationships, and the encounters range from the farcical (two women fighting over a man with the man vainly caught up in the midst of their struggle) to the painful (a teacher accused of sexually assaulting a pupil), to the grotesque (two women cleaners in a warehouse beneath a hanging corpse of a man who is related to a third cleaner who has not yet noticed his dangling body); and the absurd (a babysitter who is asked by the returning parents where their children are and claims that there were no children there in the first place). Thus the tone seems to vary from scene to scene, although the basic theme remains. Problems and conflicts between the sexes are a common theme in contemporary domestic drama ranging from the acerbic confrontations in Edward Albee’s classic play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf to the desperate and seriously farcical situations in the plays of Alan Ayckbourn. Pommerat’s play sadly bears no comparison with either. Perhaps this can be attributed to the production that slowly degenerated into a succession of harmlessly humorous sketches featuring caricatures rather than characters. From my own experience, I can say that there is a great danger involved when improvised texts are taken over into another production; dialogue that appears to be a natural embodiment in the original show because it comes from a deeply felt personal source can sound extremely superficial when the director or actor involved in a follow-up fails to get beneath the surface. This was sadly the case with the Frankfurt ensemble, for the evening seemed to go on forever.

A few days later I saw a far more impressive example of contemporary French drama, albeit still on the level of domestic boulevard comedy. The Father by Florian Zeller—despite his name, the author is indeed French and not German!—was a courageous and inventive example of how to treat the theme of Alzheimer’s disease both painfully, humorously, and realistically, yet in an occasionally surrealistic manner. It is no surprise that the author chose to call his play a “tragic farce.” The plot is straightforward: André, played here with huge panache by Volker Lechtenbrink, is the aging father of two daughters. One of them has tragically died, and the other, Anne, is faced with the dismal prospect of having to care for a man whose mind is gradually falling to pieces. What makes Zeller’s play so remarkable is that it seeks to look at the perspective of dementia from the point of view of the person affected. Thus the audience is not only presented with seemingly contradictory scenes—is Anne single and about to join a new partner in London, or is she married to a man called Pierre and living in Paris?—but also with scenes which seem weirdly repetitive such as an evening meal with chicken as its main dish, or the fact that André is continually losing his watch, deliberately or otherwise. Whatever the case he has a painful sense that something strange is happening to him “as if I had little holes. In my memory.” At times he feels threatened and persecuted by other characters, and gives vent to his frustration in bouts of fury. At other times he feels completely superior, to the extent that he accuses his daughter of being forgetful. One memorable scene in the play is when he dances like a young man before a new female caregiver as if to prove that he is not only physically but also mentally fit. In another scene, the world is turned upside down as the father degenerates into the role of a helpless little boy sobbing on the shoulder of his daughter as if she were his mother. All this confusion is mirrored first in the fact that similarly dressed characters come and go and we, as the audience, are unsure whether they are real or fictional, and secondly in the set that, at first, seems to be a fixed realistic domestic interior. But, as the play moves from scene to scene, the walls shift spatially and the seating changes accordingly, so that we are never sure whether we are in André’s own home or that of his daughter. At the end, when the lonely old man is lying in a hospital bed in the middle of a bare room, it is ambiguous as to whether we are now in an anonymous nursing facility or stranded in a pitiless metaphor for his current state of mind and future prospects. The Father premiered in Paris in 2012 and seems to have been running for the past three years. In 2014, it was awarded the prestigious Prix Molière for the season’s best play.

The French periodical L’Express has called Zeller the best contemporary French dramatist alongside Yasmina Reza, whose plays Art and The God of Carnage have been commercial successes all over the world, and deservedly so. Reza apparently wrote her latest play Bella Figura especially for the Schaubühne in Berlin. What artistic director would turn down such a prize? And indeed Thomas Ostermeier, the Intendant of the Schaubühne, not only elected to direct the play himself but also to engage Nina Hoss, one of Germany’s most talented stage and film actresses, to play the main role. Reza is famous for presenting us with provocative dialogue scratching away at the facade of the French bourgeoisie, and this play is no exception. Unfortunately, Bella Figura is so badly constructed that it might also be an object lesson in how not to write a play. It opens one evening in a deserted car park in front of a restaurant, where Boris, a successful businessman in his mid-forties is standing beside his car in an irritated discussion with his mistress, Andrea, a drug store assistant and single mother. Boris’s wife is away from home and he has taken the chance to invite Andrea for an evening meal before spending the night together in a nearby hotel. On the way to the restaurant he lets slip that this particular restaurant has been recommended by his wife. Andrea is furious and feels somehow humiliated by the remark. There follows a seemingly endless scene in which the two bicker with one another before Boris decides to back his car up into a proper parking place. In doing so he manages to knock down an old lady who has arrived with her daughter and her daughter’s partner to celebrate her birthday. As it so happens the daughter is the best friend of Boris’s wife.

But what makes the basic situation so unbelievable is that, although the old lady has been floored by the car, she not only gets to her feet immediately but everyone including the author assumes that she is completely fit once again. Thus we are asked to ignore any possible medical checks or even legal claims and go along with the author’s desire to create a situation that brings all the characters into conflict. Boris, of course, wishes to escape from the situation immediately. But Andrea decides to take petty revenge on him by insisting they accept an invitation to dine with the other three. From then on there is little development in the play apart from the fact that we learn that Boris is almost bankrupt as a result of a fatal business miscalculation, and that the characters become more and more intoxicated and irritable with one another. The dialogue sparks to life from time to time, only to splutter and die once again. The failure of the author to provide us with an organically dynamic plot is only emphasised in the director’s idea to have the actors seated across a table on an almost continually revolving set behind a huge projections of locusts, just in case we do not get the message. When the scene does move from the restaurant terrace it ends up in a woman’s toilet where Boris and Andrea engage in a “quickie”, only to be disturbed by the old lady who is desperate for a pee, an encounter that is more crude than comic because here—for the benefit of the audience? —the walls of the toilet are transparent and leave nothing to our imaginations.

Shortly afterwards, for reasons known only to the author (perhaps she wanted to ensure she had a full-length play), Boris actually cancels a taxi that Andrea has ordered, thereby contradicting his original wish to get out of the situation as quickly as possible. And so the play, like its characters stumbles on desperately to its disintegrated end, where the two protagonists once more engage in an endless dialogue before putting the audience out of its mercy. It might have been better for all if the two protagonists had simply forgotten the meal and headed for the hotel.

One of the acknowledged masters of the theatre of the absurd was Eugène Ionesco. In Recklinghausen, the Festival Intendant, Frank Hoffmann, elected to direct a revival of his first three act play, Rhinoceros. Rhinoceros originally premiered in 1959 at the height of Ionesco’s fame, curiously enough not in France, but in a German translation in Düsseldorf. This production was followed a few months later by the French premiere directed by Jean-Louis Barrault at the Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe in Paris, and at The Royal Court Theatre in London in a production by Orson Welles starring Laurence Olivier as Berenger and his wife, Joan Plowright, as Daisy. Clearly the play was then considered to be an outstanding piece of work. But time has taken its toll on the text and when I read it again I was amazed at just how verbose and predictable it was. To my gratification, Frank Hoffmann had already come to the same conclusion, and what might have been an almost four-hour ordeal was reduced to an evening of ninety-five minutes without an interval. Ionesco’s text gives us endlessly detailed information about realistic settings as if he expected his directors to “paint by numbers”. At the start of the first act, Hoffmann dispenses with the author’s instructions to show us two men sitting at a café table outside a grocer’s store in a French provincial town. Instead we first meet the two men, Bérenger and his best friend Jean (for clarity I shall use the French names here although they were all Germanised in the Recklinghausen production), arguing in the midst of the audience with the lights still up and the curtain closed. Their extremely amusing exchange is made all the more so by the chaos in which they move around the audience, and the clever way their dialogue is rhythmically counterpointed by the other characters—also moving around the audience—who are supposed to be populating the town that has been invaded by a herd of trampling rhinoceroses. As the play progresses inwardly from the public square, to an office and from there to Jean’s flat and Bérenger’s home, more and more inhabitants, including Jean, are transformed into rhinoceroses and join the herd. Finally Bérenger is abandoned by his only love Daisy and remains alone refusing to capitulate to the animal mass that is threatening to overwhelm him.

The storyline of Rhinoceros is simply too thin to sustain three acts. For, once we know that almost everybody is going to be transformed into a rhinoceros sooner or later, there are no more twists in the plot. Hoffmann’s version was a brave attempt to breathe life into the text by slimming it down to the same size as Ionesco’s best one-act plays that include The Bald Soprano and The Lesson. In this he was brilliantly served by the two main protagonists played by Wolfram Koch and Samuel Finzi whose acting was nothing less than a master class in comic interplay.

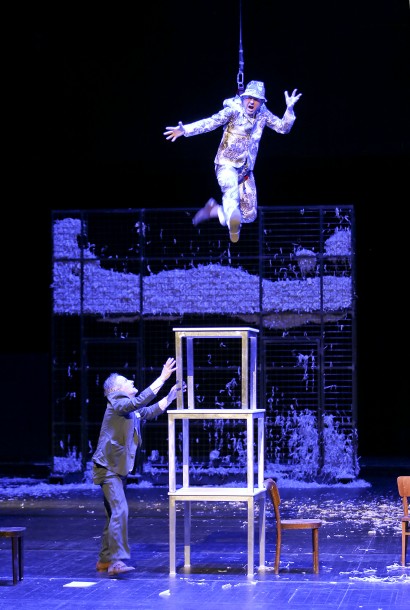

From the very start, Ionesco’s play has been interpreted as a parable of Nazi oppression. But although the playwright himself endured many manifestations of political dictatorship he always resented this attempt to portray him as an ideological writer. As he put it himself in a 1958 open letter to Kenneth Tynan: “To deliver a message to the world, to wish to direct its course, to save it, is the business of the founders of religions, of the moralists and the politicians…A playwright simply writes plays in which he can offer only a testimony, not a didactic message.” To reinforce this, in his book The Theatre of the Absurd, Martin Esslin rightly points out that Ionesco refuses to formulate any conceptual ideas of politics and morality but rather tries to communicate “what it feels like to be in the situations concerned. It is precisely against the fallacy that the fruits of human experience can be transmitted in the form of pre-packed, neatly formulated conceptual pills that his theatre is directed…To wake up the audience, to deepen their awareness of the human condition, to make them experience what Bérenger experiences is the real purpose of Ionesco’s play.” In this production, however, the audience was at no time given the impression that the world was being overrun by thousands of rhinoceroses, for every time they “appeared” Hoffmann chose to give us a blackout rather than follow Ionesco’s instructions to bombard us with a deafening sound of trampling hooves and trumpeting beasts. Nor did any of the characters ever show physical signs of being transformed into a rhinoceros. Whereas Ionesco demanded that rhinoceros heads increasingly appear on all sides, Hoffmann’s only acknowledgement of any physical change was an attractively patterned suit and hat worn by Jean as he ostensibly lost his humanity. To make the situation even more absurd this earthbound “rhinoceros” proceeded to fly around the stage suspended on a cable from the ceiling before finally disappearing. Nor was the production helped by the set during the “second” and “third” acts. For instead of slowly being destroyed by the invading animals it was simply covered in a mass of strips of white paper covering the floor and clinging to cage-like metal surroundings. Hence, in the final scene Bérenger was utterly isolated—and almost protected—from the rest of the world, rather than threatened by it. And how could he have been? From start to finish Hoffman intended us, the audience, to represent the mass of future beasts. But since we were not aware of the fact, it was impossible for us to imagine what it felt like for Bérenger to face us.

Just a few miles down the road from Recklinghausen is the famous Bochum playhouse that has witnessed legendary productions by the likes of Peter Zadek and Claus Peymann. Currently, however, the theatre is struggling to find a way to match, let alone outdo, the shows that have given it such a reputation. By contrast, the theatre in the neighbouring city of Dortmund (mostly known around the world for its soccer team, BVB Borussia Dortmund) has been making the headlines over the past two seasons under the leadership of its Intendant, Kay Vosges. Since Vosges’s shows have a reputation of using videos à la Frank Castorf (of the Berlin Volksbühne), and I have a natural allergy to this sort of theatre, I put aside my prejudices and decided to take a risk with a production of one of the greatest stage plays ever written: Shakespeare’s Hamlet. What a surprise! “The world is out of joint” and Kay Vosges mirrors this by cutting the play up into non-chronological scenes, starting in act 5 with Hamlet alone on stage with Yorick’s skull, and casting the central role with a woman. To emphasize this dislocation even further he uses videos, not for ten percent of the evening, nor even thirty or fifity percent, but almost 100% of the time. Here the Dortmund stage is flooded with video projections, magnified, pixelated, and multiplied on split screens behind a forbidding black wall inscribed with the name “Helsingkor.”

Eva Verena Müller as Hamlet and Bettina Lieder as Ophelia in The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark directed by Kay Vosges. Photo credit: Edi Szekely.

Something is indeed “rotten in the state…” of Denmark? No. Here we are in a contemporary world where the apparatus of state power is hidden from the eyes of its citizens behind barriers, and where surveillance is all-pervasive. Correspondingly the stage action takes place behind the scenes in secret; the actors do indeed play live but, by a nice ironic reversal, it is only due to surveillance cameras that the audience is able to see the unscrupulous political machinations of the court. Denmark is a police state, Hamlet’s father a human rights activist who has been assassinated by Claudius in his role as quasi-CIA terrorist opponent, and Hamlet a bespectacled, infantilized, androgynous adolescent with a cropped platinum wig, Batman belt, and costume lost in a (cyber)world of life-sized teddy bears, out of his depth and impotent in a trashy “telenovela” world. Not that our hero is against surveillance techniques. When (s)he cross-questions Ophelia (s)he is armed not only with a homemade lie detector but shoots her with a plastic machine gun for every wrong answer. Polonius is far from being a doddery old father: here he is shown in the role of horror film surgeon dissecting his daughter on an operating table and dictating to his children the rules of how to behave in a police state. Needless to say, when Hamlet meets Ophelia privately they are surveyed on screen by Claudius and Polonius. In the flood of imagery, it is left to Laertes to play the role of whistleblower à la Edward Snowden. “All we do is react!” he screams. Even at the end, Vosges is good for a surprise. Instead of a conventional curtain call, the two actors playing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern reappear once more as clowns in a landscape full of fluffy animals to invite us to send them our reactions to the show from our smartphones. These reactions are promptly shown on screen with a “thank you for giving us your data!” Thus Voges and his dramaturgs succeed in transforming a deeply political analysis into a highly associative, “virtual” dramatic experience that can only be absorbed on a nonrational level. The message is clear: in the modern world of global information the vast majority of us are trapped in the hands of those in power. I fear he is right but can only hope he is not. This production is simply unique. Let’s hope for the sake of theatre, it stays that way. Whatever the case, it was good enough to be children’s theatre.

Roy Kift is an English playwright who has been resident in Germany for many years. His latest plays are an apocalyptic farce for six actors—with video projections!—entitled The Day God went on Facebook; and a large-scale political drama (Eden’s Garden), about the Allied betrayal of Poland and its Jewish population during the Second World War. He also features in a recent documentary film called The Cabaret of Death, which won first prize at the 2015 New York Film Festival.

European Stages, vol. 5, no. 1 (Fall 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elyse Singer, Managing Editor

Clio Unger, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Avignon the 69th Festival, July 4 to 25, 2015: Discovery Beyond The Classics by Philippa Wehle

- The 2015 Oslo International Festival at Black Box Theatre by Andrew Friedman

- The 2015 Theatertreffen by Marvin Carlson

- A Feminist Tuberculosis Melodrama: Melek by Theatre Painted Bird by Emre Erdem

- Nachtasyl at the Berliner Schaubühne: A Radical View of Gorky’s The Lower Depths by Beate Hein Bennett

- From Spectacular to Minimalist: Four Plays in Madrid, April 2015 by Phyllis Zatlin

- European productions at Montreal’s Transamériques Festival 2015 by Philippa Wehle

- Childish or Adult? Recent productions in Germany by Roy Kift

- Russian Drama in Finland by Pirkko Koski

- Troubling Cross-Currents in the Budapest National Theatre by Marvin Carlson

- Spain: Engaging with la Crisis Through Theatre by Maria Delgado

- Life and Death in the Emergency Room: Linus Tunström’s Faust 1 at the Staatsschauspiel Dresden by Bryce Lease

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016