During a week’s visit to Madrid in the fall of 2014, I saw six productions. All but one of these was in the little auditorium of a larger playhouse, in a new alternative theatre, or in a cultural center. Except for the show on the main stage of the municipal Teatro Español, the plays were two-handers or monologues. I could, of course, have chosen other works from among the 167 listed in the Guía del ocio—exclusive of children’s plays, dance performances, and musicals—but for various reasons I chose both productions at the Teatro Español [El loco de los balcones, by Mario Vargas Llosa; La plaza del Diamante, by Mercè Rodereda (adapted from her novel in Catalan by Joan Ollé, trans. by Celina Alegre and Pere Rovira)]; Las heridas del viento, by Juan Carlos Rubio at the Lara; La maratón de Nueva York by Edoardo Erba (trans. from Italian by Carles Fernández Giua), at La Pensión de las Pulgas; La llegada de los bárbaros, by José Luis Alonso de Santos at El Umbral de Primavera; and Una mujer en la ventana, by Franz Xaver Kroetz (trans. from German by Manuel Heredia) at the Centro Cultural de Lavapiés.

The Teatro Español has a new director: Juan Carlos Pérez de la Fuente. He assumed this position in July 2014 but previously was director of the Centro Dramático Nacional (1996-2004). On Monday, 13 October, I attended the presentation of the annual Lope de Vega Prize for a play script. The prize includes a staging at the municipal theatre, although historically that promise has not always been fulfilled. The co-winners, chosen in December 2013, were Yolanda García Serrano and Juan Carlos Rubio for their text Shakespeare nunca estuvo aquí. Madrid mayor Ana Botella urged Pérez de la Fuente to promote Spanish theatre and to guarantee a production at Teatro Español of the prize-winning play. The director assured her and the audience he would.

The fall 2014 schedule for the Teatro Español was most likely in place long before Pérez de la Fuente assumed his new role. Spanish playwrights I spoke to prior to seeing the Vargas Llosa production told me that it was not well received on opening night. They consider the Nobel Prize winner, who is a native of Peru but has also held Spanish citizenship since 1993, to be a novelist, not a playwright. One of them went so far as to suggest that the plot would have yielded a good short story. The part of the stage set I could see during the presentation of the Lope de Vega Prize was intriguing, and I thought my reaction to El loco de los balcones might be more enthusiastic than that of my friends. It was not.

The intriguing, large-scale old balcony, stage left, was the only “building.” All the other balconies that the “crazy” Professor Brunelli (José Sacristán)—a character based on a real art historian—was trying to save from the developers who would destroy the old city of Lima were represented by boxes on the floor, stage right, or even smaller replicas of balconies on the upstage wall. José Sacristán is a popular actor of stage and screen, but he could not save the production. The conflict with his previously dutiful daughter (Candela Serrat), who decides to rebel, provided a brief dramatic moment. On Tuesday, 14 October, El loco de los balcones played to a full house in the 725-seat theatre, and the audience applauded wildly. I began to question my critical judgment until Sacristán, during the curtain calls, addressed the spectators to recognize his 80 neighbors from Chichón who were in attendance that evening.

There could be no doubt about the merit of La plaza del Diamante on the little stage at the Teatro Español. It was among five plays and two musicals highlighted in the weekly Guía del Ocio as critical successes. The “sold out” notice was posted at the box office early every day I passed by in Madrid. Mercé Rodoreda’s work, on which this monologue is based, is often called the greatest Catalan novel of the twentieth century. It was made into a movie more than thirty years before the theatrical version was first staged in 2008, during activities marking the centennial of the author’s birth. The current production is directed by the man responsible for the play adaptation in Catalan, Joan Ollé, and stars Lolita Flores.

The other monologue I discuss here, Una mujer en la ventana, makes admirable use of numerous props in order to create dramatic action, but Flores, in her portrayal of Colometa, expresses her anguish and memories without such help. There is no lack of drama, all of it coming from within the character. The set consists of a bare park bench; on occasion the colored lights that evoke the Barcelona Plaza of her memories, are illuminated. Lighting effects, designed by Lionel Spycher, and musical passages, composed by Pascal Comelade, underscore her changing emotions.

The novel, first published in 1962, is written as a first-person narrative, with only occasional lines of dialogue. In her long monologue, the working-class protagonist recounts her difficult life, before, during, and after the Spanish Civil War. She speaks of being motherless and lacking guidance when she first meets her future husband, who dominates her and replaces her real name, Natalia, with Colometa (dove). She reveals her growing dismay at how he fills their apartment with doves that make the place filthy. When she and her two children are starving after the Civil War, she is saved by a kindly shopkeeper who first gives her a job cleaning his house and then marries her.

Lolita Flores’s portrayal of the character is spellbinding. She effectively recreates the dialogue from the narrative by changing her voice to convey what others said to her. She speaks directly to the audience and raises her voice only once while nevertheless conveying a full range of emotions. She uses her hands in small gestures to reveal her inner anguish.

The Spanish friend who attended this play with me and I both thought of another novel that in 1979 was turned into an admirable stage monologue: Miguel Delibes’s 1966 Cinco horas con Mario, directed by Josefina Molina and performed by Lola Herrera. The language of the two monologues is drawn very closely from their respective narrative sources.

Las heridas del viento (Wounds from the Wind), written and directed by Juan Carlos Rubio, is also among the plays rated a critical success in Madrid’s weekly entertainment guide. The work, a profound psychological study with touches of poetry and humor, was written in 1999 and published by Editorial La Avispa in 2004. It has been performed in Greece, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Costa Rica and the United States. There was an unsuccessful attempt to translate the poetic text to English in 2002, but stagings in Miami and New York have been in Spanish.

The play, which is performed without an intermission, was written for two male actors but has since been adapted. Rubio has been collaborating for some ten years with Kiti Mánver, the prize-winning woman actor who creates Juan. Recognizing her role, Rubio has added to the original text a silent, cross-dressing scene at the beginning in which a man in drag enters and then changes into male clothing. The transformation in full view of the audience immerses spectators into the concept of gender as a construct.

The father of David (Dani Muriel) has recently died and David’s brothers have asked him, an unemployed architect, to go through the deceased lawyer’s papers and other belongings. In the process, David discovers love letters hidden away in a locked box. Those letters were written to his straight-laced, methodical, rigid father by a man. The son—who may himself be gay despite his protests to the contrary—is stunned and determines to find the author of the letters. The meetings between the two men are carried out in episodic fashion over a period of time.

The audience quickly forgets that a woman is playing the role of a man who first appears as a woman. Without any noticeable effort to drop the level of her voice, she convincingly portrays Juan, whose deep love of David’s father was not reciprocated despite the lawyer’s hiding his letters away for years. Eventually Juan shows David blank pages that his father sent Juan in response to his passionate correspondence.

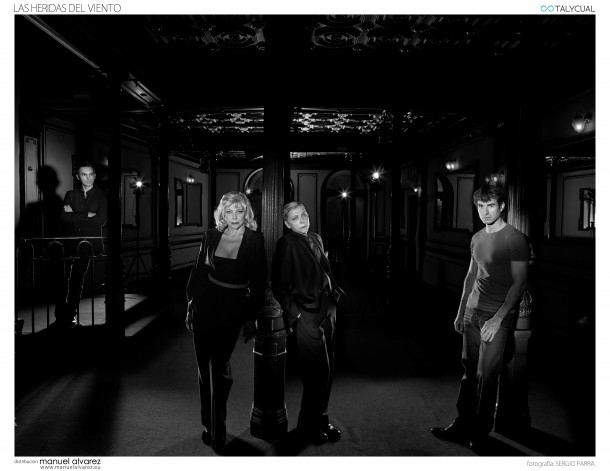

Las heridas del viento (Wounds from the Wind), written and directed by Juan Carlos Rubio. Photo credits: Sergio Parra

The special photo that the author has kindly provided reveals the dual nature of both characters in this two-hander play.

David feels he has never really known his father and still does not at play’s end. His only lasting memories are of one moment of tenderness when he is terrified by the movie Bambi and a severe punishment for finding and eating some candies. David has also not yet found himself.

I saw Rubio’s Las heridas del viento on Wednesday, 15 October, after attending the Vargas Llosa play and another two-hander, La maratón de Nueva York. Of these three, Rubio’s play for me was definitely the most dramatic and theatrical.

The historic, 420-Lara Theatre has long been called “La bonbonera”—literally a candy box—because of its cozy, attractive appearance. Las heridas del viento was not held in that main stage. Rather it was in the basement with seating for some hundred people on mismatched chairs. It was sold out the night I attended. The playing space consisted of a bare floor, with decorated columns that apparently support the building, and minimal props. The actors move their two chairs around to convey change of scene and passage of time. There are also modest changes in their costumes. For example, Juan puts on a suit jacket and tie when he goes to see David, who has not returned to visit him. The basic success of the production, however, is dependent upon the high quality acting of Manver and Muriel.

The Lara has changed its approach to programming considerably since I last attended a production there. Las heridas del viento was scheduled this fall only on Wednesday from 1 October to 17 December. Fifteen plays were being rotated between the two theatres for one or more nights a week, either in the basement or after the performance on the main stage. The feature attraction was Jordi Galcerán’s comedy Burundanga, now in its third season, which was scheduled Tuesday through Sunday, with two performances on Saturday. Indeed plays by or adapted by the Catalan playwright Galcerán, author of El método Grunholm (See WES 19.2, Spring 2007) were being performed at three different theatres in Madrid while I was there.

I was attracted to La maratón de Nueva York not because I once ran the New York City Marathon myself but because it was one of seven plays being rotated through the little fringe theatre, La Pensión de las Pulgas. Antonio Muñoz de Mesa’s La visita was staged there last year after premiering at the Teatro Arenal (See ES 1.1, Fall 2013) and I was curious to see this new space. I am told that a short story writer once stayed at a boarding house in the building on Huertas and found it invaded by fleas: hence the unusual name. It has seating for thirty-five, on reasonably comfortable padded benches located along all four walls. Spectators enter through a door on the side of the room opposite windows on the street side. Actors enter through a curtained doorway on the same wall as the audience entrance. For this production, when the spectators come in, one actor is lying face down on the carpeted floor in the middle of the room.

The play, which is being performed three times a week, features two friends, Roberto (Chechu Moltó) and Mario (Joaquín Mollá). At the insistence of Roberto, they are training together for the marathon. Before long we realize that the prone, shoeless actor is the exhausted Mario, who was resting—with one running shoe near him and the other out in the entrance hall. As they run in place for most of the fifty-five minutes of the action, they talk about running, about their childhoods, about their friendship, about being rivals for a woman’s affection. By the end of the performance, they have both had a real workout. When I attended late afternoon on Sunday, 12 October, about half of the seats were empty and only about half of the spectators appeared to be following the dialogue. The space and scheduling is interesting, but this play for me was not.

Much livelier than the men running in place was José Luis Alonso de Santos’s La llegada de los bárbaros, held in El Umbral de Primavera, another new alternative theatre, with about the same seating capacity as La Pensión de las Pulgas. El Umbral de Primavera opened last spring and is part of the consortium Lavapiés Barrio de Teatros that was created in February 2014. The network consists of fifteen little theatres in the Lavapiés neighborhood and promotes a special subscription that covers them all. The group of theatres collectively has more than 1,000 seats and offers some 400 productions a month. In October the Alonso de Santos absurdist farce was being performed on Friday and Saturday evenings in rotation with various other plays.

The two characters of La llegada de los bárbaros are a man in a gray suit (Yiyo Alonso) and a security guard (Juan Alberto López). The theatre lobby is a large space with chairs, tables, and a sofa where spectators may enjoy refreshments before the show begins. On Saturday, 18 October, the beginning of the performance was delayed slightly for technical reasons, and the uniformed security guard walked around the lobby and stood at the outside door, as if he were in fact guarding the theatre. Had I not overheard someone asking the actor to do this, I would have assumed that it was always a part of the performance. Perhaps it still was and the line I overheard is repeated each evening.

The only set for the play is a park bench. The man in gray enters with a suitcase and sits down. The guard appears and tells him that sitting on the bench is prohibited. The guard’s main responsibility is to keep people off the bench and he worries that a supervisor will find out if he fails in that function and fire him. He asks if the man in gray is a supervisor.

The man in gray is a Latin teacher who has just lost his job, his wife, and his home. All of his worldly possessions are in the suitcase. He wants to sit for a few minutes and read his newspaper. What ensues is a cat-and-mouse game, typical of two handers, with lots of slapstick action and wordplay. The park bench in La plaza del Diamante is a place to sit sedately; the park bench in this play is the site of hiding, running and jumping as the two men challenge one another. The two actors get a workout in this production comparable to that of the would-be marathoners in the play at the Pensión de Pulgas.

The guard rips up the newspaper and a special Latin text. When he opens the suitcase, it turns out to be a box of surprises. It is filled with an amusing assortment of unlikely items, including a globe and a rubber chicken, that are then strewn around the stage area. Among these props are balloons, which are inflated one by one and popped. Although there were touches of humor in all six of the plays I saw this October in Madrid, the Alonso de Santos text was the only comedy among them.

Yiyo Alonso and Juan Alberto López in La llegada de los bárbaros. Photo courtesy of José Luis Alonso de Santos.

Underscoring the constant surface farce, perhaps there is a serious satirical message. There is no place for a Latin teacher in a society dominated by computers. The book the man in gray carries with him tells of the fall of the Roman Empire. Among today’s barbarians are police and judges who conspire against an outcast like him. But any serious message is quickly set aside when the man in gray does a complete reversal in character. Now speaking in a formal tone, he announces that he is the supervisor; the guard, who has failed to protect the park bench, is fired.

Not counting volunteers and crew members who joined the audience, there were some twenty spectators, most of them relatively young. They laughed frequently and obviously enjoyed the play.

On Thursday of my week in Madrid, I chose a production directed by Juan Margallo and starring his wife, the acclaimed actor Petra Martínez. In 2013, when I attended La visita by their son-in-law Antonio Muñoz de Mesa, I realized that I had never seen Petra Martínez perform. The play being staged in fall 2014 by Uroc Teatro was a traveling production with just a day or two in each place. There was only one performance convenient for me—at the cultural center of Lavapiés—and I built my week’s theatre choices around it. I was not disappointed. Petra Martínez lived up to her reputation. Indeed I was fortunate during this trip in seeing three of Spain’s outstanding women actors perform: Petra Martínez, Lolita Flores, and Kiti Mánver.

Like La plaza del Diamante, Una mujer en la ventana is a monologue. Whereas the former is performed virtually without props, the latter production had the only detailed, realistic set of the six plays I saw. The experienced crew struck the set and packed it away with amazing speed to prepare for the company’s departure from Lavapiés immediately after the show.

Stage right was a kitchen area, with hanging pots, a stovetop, a large wooden cupboard with counter space and drawers, and an old-fashioned radio. A table and chairs completed the dining area. The window of the title was located in the center of the upstage wall. Other furniture included a couch with several toss pillows set behind an area rug, a bookcase and a floor lamp. Upstage left was a closet, concealed by a curtain that could be drawn back to reveal the woman’s clothing. Walls were decorated with family portraits and paintings and shelves were lined with knickknacks—the treasures the woman had acquired over a lifetime.

The German play was first staged in Madrid some thirty years ago, but the set suggests that the woman has been living in her home for many years, perhaps dating to the postwar period. The elderly woman relives memories from the early years of her marriage. Although some of her anecdotes are told in humorous tone, her sad story is universal.

In good health, mentally and physically, she is being forced to leave her home, give up most of her belongings, and move into a nursing home. She has been told that her building is being torn down and she must vacate. Her son says there is no room for her in his home. She is somewhat consoled by her grandchildren, who say they will take care of her beloved canary. Residents in the nursing home are not allowed to have pets. Moreover, she will be sharing a room and there will not be space for many of her things. She fears she will not be allowed to cook or do anything useful.

The monologue is enlivened by the woman’s talking at times to the canary, at times to herself, and at times to the audience. There is nothing static about the staging as she moves about the set, trying to identify items she will be allowed to take with her. She starts piling them on the table and chairs. When she rejects an item—as she does initially with the canary—she provides an explanation that she has no doubt been told over and over by her son about rules and regulations. She owns few dresses but is even selective about them. She tries to remain cheerful and rationalize the radical change in her life, but in the end she breaks down. In a moment of rebellion she throws a knickknack at the window, breaking the glass. That action comes as a surprise, but throughout we feel the woman’s pain.

The auditorium in the Lavapiés cultural center is smaller than other venues where the production has been traveling over the past months. An audience of about fifty filled the space. Admission was free and people came well before curtain time to be sure of getting in. Petra Martínez’s outstanding performance was acknowledged with enthusiastic applause and several curtain calls.

During my brief visit to Madrid, I saw four excellent productions and discovered new little theatres that are successfully attracting audiences. Despite the continuing impact of the recession in Spain, because of creative scheduling and talented performances, the Spanish stage is alive and well.

is Professor Emerita of Spanish and former coordinator of translator-interpreter training at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. She served as Associate Editor of Estreno from 1992 to 2001 and as editor of the translation series ESTRENO Plays from 1998 to 2005. Her translations that have been published and/or staged include plays by J.L. Alonso de Santos, Jean-Paul Daumas, Eduardo Manet, Francisco Nieva, Itziar Pascual, Paloma Pedrero, and Jaime Salom. Her most recent book is Theatrical Translation and Film Adaptation: A Practitioner’s View. See www.rci.rutgers.edu/~zatlin.

European Stages, vol. 4, no. 1 (Spring 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elizabeth Hickman, Managing Editor

Bhargav Rani, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Report from Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- Performing Protest/Protesting Performance: Golgota Picnic in Warsaw by Chris Rzonca

- A Mad World My Masters at the Barbican by Marvin Carlson

- Grief, Family, Politics, but no Passion: Ivo van Hove’s Antigone by Erik Abbott

- Not Not I: Undoing Representation with Dead Centre’s Lippy by Daniel Sack

- In the Name of Our Peasants: History and Identity in Ukrainian and Polish Contemporary Theatre by Oksana Dudko

- Performances at a Symposium: “Theatre as a Laboratory for Community Interaction” at Odin Teatret, Holstebro, Denmark, May, 2014 by Seth Baumrin

- Songs of Lear by the Polish Song of the Goat Theatre by Lauren Dubowski

- Silence, Shakespeare and the Art of Taking Sides, Report from Barcelona by Maria M. Delgado

- Little Theatres and Small Casts: Madrid Stage in October 2014 by Phyllis Zatlin

- Gobrowicz’s and Ronconi’s Pornography without Scandal by Daniele Vianello

- Majster a Margaréta in Teatro Tatro, Slovakia by Miroslav Ballay

- Remnants of the Welfare State: A Community of Humans and Other Animals on the Main Stage of the Finnish National Theatre by Outi Lahtinen

- Mnouchkine’s Macbeth at the Cartoucherie by Marvin Carlson

- Awantura Warszawska and History in the Making: Michał Zadara’s Docudrama, Warsaw Uprising Museum, August, 2011 by Krystyna Illakowicz and Chris Rzonca

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016