Watching Lluís Homar’s Cyrano in a new adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play at Barcelona’s Borràs theatre, the ghosts of the actor’s earlier roles tumble out in quick succession. The wispy, thinning grey hair no longer cascades as it did when Homar charmed audiences as the quick-witted Figaro in Beaumarchais’s The Marriage of Figaro in 1989. There are echoes of his 1999 Hamlet in the reflective soliloquies. The complicit relationship with the audience also harks back to Homar’s tour de force performance in Àngel Guimerà’s Terra baixa / Marta of the Lowlands in 2014. Indeed, Rostand’s Cyrano shares features with Guimera’s text: both are contemporary classics, the latter often seen as Catalonia’s most celebrated play. Premiering in 1896 in Nobel prize-winner José Echegaray’s translation, it became the most emblematic role of iconic Catalan actor Enric Borràs—who had performed it over 1000 times by 1908. Broadway productions and operatic and filmic configurations followed. Cyrano premiered just a year later than Terra baixa and has enjoyed conspicuous success, with no less than 10 cinematic reworkings, and three operas. Its Catalan journeys include Josep Maria Flotats’ 1985 now legendary staging and Oriol Broggi’s playful production at the Biblioteca de Catalunya in 2012 with Pere Arquillué in the title role.

Both Cyrano and Terra baixa share the same creative team: the dramaturgy and direction are by Pau Miró; the set by Lluc Castells; the Catalan National Theatre’s artistic director Xavier Albertí shares responsibility for the lighting; music is by Silvia Pérez Cruz. For Terra baixa, Homar took on all of the play’s roles, a dialogue with the 1975 staging by Fabià Puigserver in which Homar took on the role of Manelic, the young man that Marta is to marry in order to mask her affair with the ferocious Sebastiá. In the 2014 production, Homar performed the play as a poem to modernity, shifting across the different roles with ease, fluidity and the simplest of gestures. Homar and Miró conceived Terra baixa as a statement on a society where tensions are contained within the individual, battles between the predatory and the pragmatic, altruism and greed, the masculine and the feminine. Guimerà’s play became less of a rural melodrama and more a statement on the tensions that represented the advent of modernity.

Miró and Homar have gone for a different approach with Cyrano de Bergerac. The reading appears less novel but still foregrounds the theatricality that so distinguished Terra baixa. Homar’s Cyrano is less the soldier and more the fool. He is a theatrical being who enjoys a playful relationship with spectators. The audience is folded into the production as Cyrano’s confidantes; Homar is a more philosophical Cyrano than either Flotats’ or Arquillué’s. He ponders and poses; he waits and deliberates. He hovers around the front of the stage addressing his deliberations and qualms to the audience. For Cyrano, Homar does not attempt a solo performance but is rather joined by four other performers. Two take on major roles: Àlex Batllori as the handsome soldier Christian that Cyrano aids in his courtship of his cousin Roxanne, where Aina Sánchez’s sharp intelligence shines through. Joan Anguera and Albert Prat take on a number of roles—the latter is more comfortable in his characterisation of the Comte de Guiche’s journey from dastardly rival to accomplice than Anguera who appears overly aloof and unengaged as Le Bret.

Lluc Castells’ set suggests something of a sports hall; two rows of theatre seats at the back of the stage reinforce the theatrical dimensions of Homar’s characterisation. The black and white palette of the set promotes a blunt aesthetic that undermines the nuanced negotiations of Homar’s Cyrano. The brilliant white suits and clinical cut of the costumes suggest a contemporary uniform. The two racks of white suits that frame the right side of the stage point to a space of disguise and representation. The sporty shoe-wear further reinforces the competitive edge. These are men vying for the attentions of a “prize” named Roxanne. The set is one where masculine prowess prevails—swords cluster on each side of the catwalk where the main action takes place with watchtowers serving also as columns for the balcony scene. Homar’s performance externalises the emotional conflict with a marked demarcation between what he feels and what he shows. He bounces across the stage. His lithe jumps render him a more agile than his younger rival for Roxanne’s affections. He skirts across the front of the stage, keeping close to the audience. He works to encourage the audience to root for him, sharing his anxieties and his intimacies, looking them in the eye as he asks them for advice. Even in the final scene, now attired in black, frail and infirm, slowed down by age and illness, and walking with a stick, he is still performing—the picaresque and the melancholy fusing to productive effect.

Albert Arribas provides a lithe, idiomatic translation, and Silvia Pérez Cruz offers musical interludes between the scenes that provide a commentary on the action: gentle, haunting humming that offers a melancholy reflection on the onstage action; a jaunty piano dominated bolero tinged with longing; an echoing unaccompanied vocal lament on loneliness. The black and white colour design, however, appears overly schematic in a play that explores different shades of grey, but the audience’s rapt applause shows the pull of Homar and the ways in which he can win over an audience to Cyrano’s losses in love and war.

Josep Maria Pou dominates the stage as Ahab in Moby Dick. Photo: David Ruano.

Like Homar, José María Pou—another giant of the Catalan stage—is an actor who knows how to hold an audience. His star turn in Moby Dick is a wonderful thing to behold. Pou is a larger than life performer—a tall, sturdy figure who increasingly feels like he belongs in another era. When I think of this actor, figures like Charles Kean and David Garrick come to mind. Don’t get me wrong, this isn’t because he feels old-fashioned or out of step with current trends. On the contrary, Pou remains alert to innovations in dramatic writing and his track record of staging new writing; this is especially true for British plays by Hare, Bennett and Harwood, where he is second to none. Pou is quite simply an actor who knows how to take an audience with him on a journey. He fills a stage, physically and dramatically. In Juan Cavestany’s feverish adaptation of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, presented at the Goya Theatre, he dominates the stage from beginning to end, a mighty Ahab who spreads across the stage like the whale he seeks to hunt down. Cavestany dispenses with narrative logic in favour of a stream of consciousness poetics where past and present meld to provide a window into Ahab’s tortured mind. In the opening moments of the piece, Ahab emerges from the darkness. Sitting in his throne-like chair, his arm waves from side to side like the pendulum of a clock. It is as if he is waking from a dream, grunting and growling like a gruff waking bear clad in a rough coat.

It is clear from the production’s opening moments that the sleep of reason has produced monsters of the mind. This Ahab is his own tormentor. Pou, Cavestany, and director Andrés Lima have conceived the piece as a manifestation of the workings of Ahab’s obsessive mind. The Pequod’s crew of 30 is here reduced to two-bit players who weave in and out of Ahab’s adventures. Ambience is substituted for storyline as the audience attempts to keep up with the shipwreck weaving through Ahab’s imagination. Valentín Álvarez’s lighting moves from spectral blue to blood red, capturing the different moods through which Ahab passes. Moby Dick remains always out of reach: a giant projection, a phantom presence, a sound in the distance.

The sleeves of Ahab’s shirt act as billowing sails as his delirious ramblings echo across the stage’s wooden surfaces. Beatriz San Juan’s set is dominated by planks of wood shaped to create the outline of a ship. Ropes and ladders are lifted to give a sense of the Pequod’s different areas, from the watchtower to the stern. A giant sail floats above Pou and his two fellow actors—Oscar Kapoya in the role of Pip, and Jacob Torres in the dual roles of Starbuck and Ismael. The latter two use on-stage wind machines to lift the sail high above them so it races above Ahab’s head. Miquel Àngel Raio’s video projections show a bubbling sea that spits and snarls in the distance. The giant shadows of sailors float across the back wall, a reminder both of lives lost at sea and Ahab’s impending fate. The spectral shapes serve as manifestations of Ahab’s wild imagination. Ominous black clouds vie with the moon which rises from the water like a giant ball. At times, the images look like an X-ray. Moby Dick’s giant eye stares out both at Ahab and at the audience. Ahab clutches a fur rug desperately as if it were a comfort blanket. He clings to Pip like a dying animal, the pain in his leg a constant source of frustration and debilitation through the course of the performance. The prosthetic leg provided by Pan’s Labyrinth’s Oscar-winning team of David Martí and Montse Ribé weighs Ahab down. A monstrous contraption, it keeps him grounded when he would wish to fly in his endeavours to hunt down Moby Dick. He drags it with him, a heavy, painful reminder of the maiming endured at the hands of the elusive Moby Dick.

Pou has noted that he has had to face Ahab “with the same passion, courage and determination with which Ahab faces the whale. With the same madness. Or perhaps even more” (Moby Dick Pressbook). His performance is a mighty tour de force and the cornerstone of the production’s success. Pou’s past roles flicker through his characterisation of Ahab. Indeed, there is much of Pou’s raging, angry Lear from 2004 in his obsessive focus. Ahab’s anger is relentless, a man at war with himself and his demons, pounding the stage like a deafening percussive sound. Oscar Kapoya’s Pip cowers in his presence, Jacob Torres’s Ismael disappears into insignificance next to him. I wondered at times if the production might not have been better served by Pou alone on stage. It felt at times as if Pip and Ismael were as much ghosts as the projections on the back screen. Tellingly Ahab incorporates lines that are attributed to Ismael in Melville’s novel. There are moments when Pou has something of Orson Welles about him—Pou’s performance as Welles in Richard France’s 2008 play about the filmmaker is yet another ghost that haunt the production. Cavestany and Lima have a long history of collaboration through the company Animalario. The production’s intensity of mood recalls their 2008 Urtaín while Jaume Manresa’s operatic score gives the piece a haunting, epic quality. It is a rollercoaster journey of fire and brimstone, thunder and lightning, crashing waves and potent storms: 80 minutes of soaring emotions and unadulterated theatricality.

Enrique (Pablo Viña) and Gonzalo (Esteban Meloni) in Josep Maria Miró’s Olvidémonos de ser turistas/Forget That We’re Tourists at the Sala Beckett. Photo: Kiku Piñol, courtesy Sala Beckett.

Over the past eight years, Josep Maria Miró has emerged as one of Spain’s most internationally visible playwrights. His 2012 play El principio de Arquímedes/The Archimedes Principle has been translated into 13 languages and enjoyed two film adaptations—the first in Catalan El virus de la por/The Virus of Fear by Ventura Pons in 2015, and the second into Portuguese by Brazilian director Carolina Jabor, Aos Teus Olhos/Liquid Truth in 2017. The Archimedes Principle premiered at the Sala Beckett in 2012, and Miró now returns to this emblematic new writing venue with a month-long season of his work. Sala Beckett relocated from Gràcia to Poble Nou in July 2016 and its expansive new building, the 1920s former Peace and Justice Cooperative, was remodeled by architects Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores into a dynamic multipurpose venue. It boasts two flexible performance spaces, further rehearsal rooms, offices and a buzzing bar-cum-restaurant. Miró’s return to Beckett brings together a series of readings, presentations and workshops with two productions: a staging of his 2013 play Nerium Park and a new work, his first written directly in Spanish, Olvidémonos de ser turistas/Forget That We’re Tourists, realized in a coproduction with Madrid’s Teatro Español and Argentine actress/director Gabriela Izcovich’s company, who presented the piece at Buenos Aires’s Teatro 25 de Mayo in August of this year. Forget That We’re Tourists is a road movie concerning a couple from Spain, Enrique (Pablo Viña) and Carmen (Lina Lambert), married for close to 30 years, who are on holiday in Foç de Iguaçú at the Triple Frontier where Brazil meets Argentina and Paraguay and the Iguazu and Paraná rivers converge. The action opens in the couple’s hotel room – a familiar location in Miró’s plays where individuals are tested in situations where they are positioned away from home in what Marc Augé terms non spaces. Enrique resents the fact that the couple have been joined by an unseen young man whose company Carmen has enjoyed. It is soon evident that the young man recalls their son—something that neither appears able or willing to talk about. He has opened up a wound that shows the fragile state of the couple’s marriage and points to a trauma that neither can face. When Carmen goes off for a cigarette that evening and doesn’t return, Enrique is left in a quandary. She had disappeared previously for a three-day spell and on her return never told him where she had been. Should he just bide his time and wait for her possible return or does her disappearance signal something more ominous?

Enric Planas’ open set gives a sense of the large void between the couple. The breadth of the empty space suggests a terrain that cannot easily be bridged. Stage right, a bare and basic hotel room where Enrique and Carmen are staying when play opens; the rest of the space allows for different pockets of action, stages on the journey that Enrique and Carmen each embark on. Eugenia Alonso and Esteban Meloni—Argentine performers who are familiar with Miró’s work through their roles in the highly successful five-season run of the San Martín theatre production of The Archimedes Principle—play the different characters that Enrique and Carmen meet on their travels. Alonso excels as Valería, the hotel cleaner in blue gloves, overalls and plimsolls with whom Enrique shares news of Carmen’s disappearance. Her blunt, no-nonsense approach contrasts with his hesitation and she dispenses with his gauche attempt to kiss her with a weary pragmatism. With a swift removal of her overalls, Alonso turns Valeria into Beatriz, a seasoned tourist guide helping to get Carmen to Catamarca.

Enrique travels with Meloni’s Mauricio, a kindly bus driver who left his job driving underground trains after seeing too many people take their own lives. He has now found a degree of peace in the long nocturnal journeys he makes across the open road. Enrique finds solace in Mauricio’s assenting philosophy. Melina, a wishful femme fatale in a tight black sequined dress, recognizes the sadness in Enrique’s face. Frequenting hotel bars in search of company, she offers not sex but conversation. And he finds her questions unsetting and uncomfortable. Each of these characters that Carmen and Enrique encounter presents a signpost on their physical and emotional journey: a way of reflecting on past decisions and of considering what to do next. Meloni and Alonso execute swift, tight role transition. Characters appear, one emerging from another like a set of Russian nesting dolls. The impression provided is of both strangeness and familiarity Carmen, Enrique and the audience. It is almost a metaphor for their journey, a journey where reminders of their son are ever-present and cannot be shaken off.

As the play unravels, the audience learns that the couple’s son, Alberto, came to Argentina in search of opportunities that Spain could no longer offer. In the play, Europe is described as an old woman whose ailments are all coming to the fore. His departure for Argentina—apparently in 2010 during Spain’s worst recession in living memory when youth unemployment reached 41.6% (2.3 times that of the population over 25)—suggests a move based, in part, on the possibility of employment. Indeed, Enrique speaks to Mauricio about Europe expelling his son—an idea that suggests the continent was not able to support its own future. Meloni’s Fabián (the young man who takes Carmen in after her accident) spins a tale of his father lost in Rome that similarly speaks of a city unable to take care of those in search of refuge. Just as Alonso shifted from Valería to Beatriz through the simplest of gestures, so did Meloni’s young, open-hearted Fabián mutate into the easy going priest Gonzalo by scrunching his hair and sporting a pair of glasses. Gonzalo attempts to bond with Enrique by presenting himself as a Martian trying to understand human beings. Enrique is disarmed by Gonzalo’s humour and breaks down in tears. Carmen finds refuge with the kindly Tía, a Paraguayan woman who relocated to Argentina, and now makes it her business to help those who need comfort or assistance. Tía took Alberto in before his death, and now offers Carmen a similar solace. Like many of the characters Enrique and Carmen encounter on their journey, Tía refuses to condemn, while Carmen and Enrique are consumed by their need to judge and by a desperation to find answers to questions that defy easy explanations.

This is not to say that the play offers a simplistic understanding of the journeys undertaken by the European characters as merely a search for solace in the Latin American other. The Argentine priest Gonzalo is leaving for an unnamed country at the border with Europe to offer humanitarian aid in a place where “no llegan cruceros pero no para de llegar gente de cualquier manera/there are no cruise ships but there’s no shortage of people who just keep arriving through any means.” Indeed, Gonzalo leaves as Fabián’s father did before him. The journey made by Fabián’s father is linked through association with the Argentine crisis when over 87,000 left in 2002 alone in search of employment abroad (La Nación, 13 August 2008). The voyage from Europe to Argentina and vice versa is part of a complex web of journeys that form one’s identify. Over four million Italians emigrated to Argentina between 1880 and 1930, and it is thought that 16 million of Argentina’s 43.8 million population have Italian roots (La Nación, 14 March 2001); a significant proportion of these also have Italian citizenship.

Tía, however, is Paraguayan born and her journey involves its own trials and tribulations. After being nearly kidnapped by the military and raped by her uncle, she left for Argentina, keeping an open door for those in search of refuge. She refuses to judge and simply listens to the stories of others to try and make sense of her own past. Let’s forget we’re tourists is a way of thinking through the journeys that mark the displacements of peoples for political, religious, economic and personal reasons.

On the back wall, the projection of photographs by Mercè Rodríguez allows for some sense of location—as with the empty roads and a mountain landscape—but these ghostly images also provide pointers to mood and action, as with Eva Peron’s portrait and the handle bars of a motorcycle. Alberto, who died in a motorcycle accident, haunts the play, a loss that’s woven through each of Enrique and Carmen’s encounters. Iscovich’s production is stark, deft and purposeful. It explores the unsaid and the unarticulated, and ensures that even in the most intimate moments, the gulf between and surrounding the characters, remains profound. Characters acknowledge the theatrical premise: Beatriz signals to Carmen that there’s a bed she can retire to; Enrique calls out to stage management to switch off Julio Iglesias’s easy-listening song “Lo mejor de tu vida/The best of your life” which plays in the hotel bar during his encounter with Melina. Items of furniture are reappropriated—a bed becomes a bench—with the same ease that Meloni and Alonso use to peel off their different characters. This is a production rooted in exceptional performances where the delicate interplay of revelation and concealment is constantly under negotiation. It’s also a treat to see the ways in which Miró weaves into the very fabric of the play an Argentina that has proved such a fertile landscape for his plays. Argentina and what it represents for the characters is not merely a motif, but a very concrete way of considering the relationship between self and other. Furthermore, Miró’s theatrical conceit never lets the play fall into the terrain of social realism. Let’s forget we’re tourists is a play about a society on the move where nothing can be taken at face value.

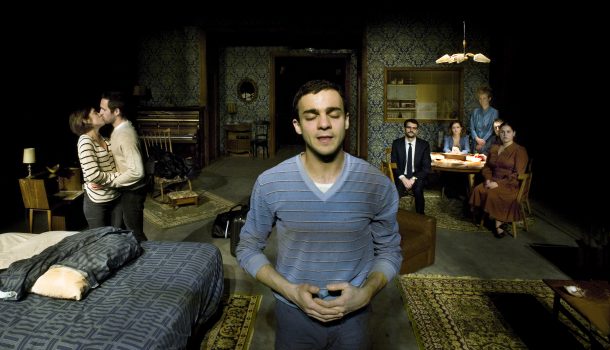

Ghosts also run through Argentine writer-director Pablo Messiez’s collaboration with the Jove Companyia (young company) at the Teatre Lliure. El temps que estiguem junts/The Time That We’re Together is a play haunted by a loss which cannot easily be articulated but that seeps through every one of the characters’ encounters, actions, and conversations.

Two parallel narratives overlap in Pablo Messiez’s El temps que estiguem junts/The Time That We’re Together at the Teatre Lliure. Photo: Ros Ribas.

The set by Elisa Sanz presents a small apartment that looks as if it’s been abandoned for some time. A kitchen at the back can be seen through a window, as well as a dining area centre-right. Old rugs litter the floor. A piano upstage right, a bed downstage right. Dust covers are positioned over the furniture and the patterned blue wallpaper harkens back to an earlier era. Three old lamps are positioned across the room. This is a flat that time forgot. Clàudia (Clàudia Benito) and Edu (Eduardo Lloveras)—in this play, characters and actors share names—are being shown around the flat by Júlia (Truyol), a woman who looks worn out by life. Their excitement is a veritable contrast to Júlia’s weary manner. The flat has been empty for five years and, as Júlia removes the dust to show Edu and Cláudia the room, human bodies are revealed. At first, they appear to be asleep. At the dining room table, however, three men are weeping. One of the men puts a record on and the ghostly persons all begin moving around the room. These five figures, joined by Júlia, are the inconsolables—a group united by loss who come together on a Saturday to support each other in light of their traumas. Some of these are revealed through the course of the play, some are merely alluded to, and others remain a mystery, still unexplained by the play’s end.

When Edu and Clàudia move into the flat, their temporality merges with the parallel lives of this self-help group (Joan Amargòs, Quim Ávila, Raquel Ferri, Andrea Ros, Joan Solé and Júlia Truyol), lost souls in search of something elusive to fill the loss that eats away at their lives. As Clàudia and Edu have sex, the inconsolables roam the room trying to make sense of a future that appears to offer them little hope. The play hinges on the ways that these two tales intersect: a couple in love moving apart alongside a group of damaged people try and find ways to move forward with their lives.

When the agitated inconsolables run desperately across the stage, searching for someone or something, they run in different directions, almost but never quite colliding, unable to work together to find an answer to their pain and grief. Raquel Ferri is aware that they are being watched, pointing unexpectedly to the audience at one point in the play. Overlapping dialogue allows the two temporal spaces to merge. Cláudia can see the inconsolables at certain moments and is frustrated that Edu cannot. When she says to him that “we don’t see the same things,” it is an indication that their relationship is falling apart.

The desperation in many of the characters is dramatized through moments of confrontation, anger or excess. Joan Solé bursts into song—underscored with a percussive rhythm of snapping fingers and slapping thighs—with energy that delivers a brief high. Joan Amargos isn’t sure what makes him so happy. The deployment of the liebestod from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde as well as reflections on love delivered by Clàudia from Sarah Kane’s Crave offer a way of articulating a vision of love rooted in a death wish: love containing its own demise. The disintegration of Clàudia and Edu’s relationship—her neediness, his pulling away—is set against the mourning and melancholia of the inconsolables. Joan Amargós makes a difficult call, attempting to come to terms with a breakup he cannot comprehend. Andrea Ros mourns the child she lost, articulating a vision of love as that which helps humanity face its fear. Raquel Ferri wants moments of peace but thinks about death constantly. She sobs inconsolably, crying that Clàudia initially attributes to the baby next door. Quim Ávila’s final monologue is Chekhovian in its poignancy; his suicide is a telling nod to The Seagull. Joan Solé stops Jùlia heading to the kitchen to see her dead son much in the way that Dorn asks Trigorin to divert Arkadina, so she doesn’t encounter the dead Treplev.

Messiez directs with a choreographer’s eye. The staging has an energy and dynamism that feels urgent and necessary. The stage space is compact but the movement never feels awkward or clumsy. The inconsolables float across the stage, darting and dancing as they move between Edu and Clàudia. There is a real poetry to Messiez’s writing, a languid sense of a life spent in limbo that owes much to Chekhov. And while the play would have benefited from some further shaving, I admired the audacity of the conceit and the liveliness of the performances. It is refreshing to see a play about young people that moves beyond the paradigms of social realism into a more magical and unsettling register.

Maria M. Delgado is Professor and Director of Research at The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London, and Honorary Fellow of the Institute for Modern Language Research at the University of London. Her books include “Other” Spanish Theatres: Erasure and Inscription on the Twentieth Century Spanish Stage (Manchester University Press, 2003, updated Spanish-language edition published by Iberoamericana/Vervuert, 2017), Federico García Lorca (Routledge, 2008), and the co-edited Contemporary European Theatre Directors (Routledge, 2010), A History of Theatre in Spain (Cambridge University Press, 2012), and A Companion to Latin American Cinema (Wiley-Blackwell, 2017). She has published two collections of translations for Methuen and is co-editor of Contemporary Theatre Review.

European Stages, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 2018)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Taylor Culbert, Managing Editor

Nick Benacerraf, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Berlin Theatre, Fall 2017 by Beate Hein Bennett

- 2018 Berliner Theatertreffen by Steve Earnest

- Speaking Out by Joanna Ostrowska & Juliusz Tyszka

- Political Theatre Season 2016-2017 in Poland by Marianna Lis

- Hymn to Love in a Love-less World: Chorus of Women, Berlin 2017 by Krystyna Lipińska Illakowicz

- Wyspiański: From Wagner, Through Brecht, to Artaud? The Curse and The Wedding in Poland Today by Lauren Dubowski

- A Theatrical and Real Encounter with Zabel Yesayan: A Play by BGST by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Vienna by Marvin Carlson

- Motus and Me: In Appreciation of the Italian Theatre Group Motus by Tom Walker

- Actors without Directors: Setkání/Encounter Festival of Theatre Schools in Brno, Czech Republic, 17-21 April 2018 by Matti Linnavuori

- Ghosts, Demons and Journeys: Barcelona Theatre 2018 by Maria M. Delgado

- Two Samples of Documentary Theatre in Hungary by Gabriella Schuller

- Two East European Festivals by Steve Wilmer

- The Misted Stage: Eirik Stubø’s Stagings of Tragedy by Eylem Ejder

- Amadeus in London by Marvin Carlson

- Two Significant Losses

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016