London’s Royal Court Theatre has premiered nearly all of Caryl Churchill’s plays for more than four decades, and audience members who purchase programs there receive a bonus: a printed copy of the script. Readers who ventured beyond the production details will have found two items central to this review of her marvelous Escaped Alone. The first is its epigraph:

“I only am escaped alone to tell thee.”

– Book of Job. Moby Dick.

The title image, “escaping alone,” evokes the solitary and perilous journey that each of us ultimately takes in this world. But the larger quote from which it is drawn—and indeed the play itself—conjures the human need for connection with others, which is often created through storytelling. Escaped Alone beautifully captures suffering on scales both commonplace and cataclysmic, while simultaneously engaging the paradox of violent impulses as they coincide with both the yearning for, and comfort found, in community.

The play’s structure juxtaposes scenes of prosaic, backyard gatherings of a group of neighborhood women with starkly staged, poetic monologues delivered by one of them; these express the playwright’s prophecies of worldwide catastrophes, as told by a woman who (apparently) survives them. A small community is represented by the women in the backyard, who share snippets of stories and memories; a larger community is represented by the audience at the Royal Court Theatre, gathered to see the play. And larger, yet, is the world to which Caryl Churchill speaks, as it is she who has, perhaps, “escaped,” to tell tales of the past, present, and prophesied future, with her singular dark humor—and wisdom.

The second reference from the printed play, which is more evident in production than is the epigraph, pertains to its cast of four female characters: Sally, Vi, Lena, and Mrs. Jarrett. About these roles (and presumably actors) Churchill makes this specific stipulation: “They are all at least seventy.” This is its own theatrical phenomenon. Can anyone recall the last time—anytime—a play was written for and about four septuagenarian women? Before seeing the Escaped Alone, I found myself thinking of Janelle Reinelt’s 2006 essay “Navigating Postfeminism: Writing Out of the Box,” in which she observed how Churchill’s plays were becoming “more removed from the familiar feminist writing of [her] Cloud 9 or Top Girls,” but optimistically noted that, though not “overly feminist,” they were “imbued with…second-wave feminism.” In Escaped Alone, one cannot help but note that Churchill is not only taking on sexism as part of her activist art, but also ageism.

Escaped Alone is another inspired and successful collaboration with director James Macdonald and designer Miriam Buether (both worked with her on the fabulous Love and Information in 2012). The play also represents Churchill’s ongoing commitments to socio-political (and feminist) writing and experiments with form. Recently, she chooses economy in both length and language: Escaped Alone is less than an hour long, and the characters frequently speak in phrases rather than sentences.

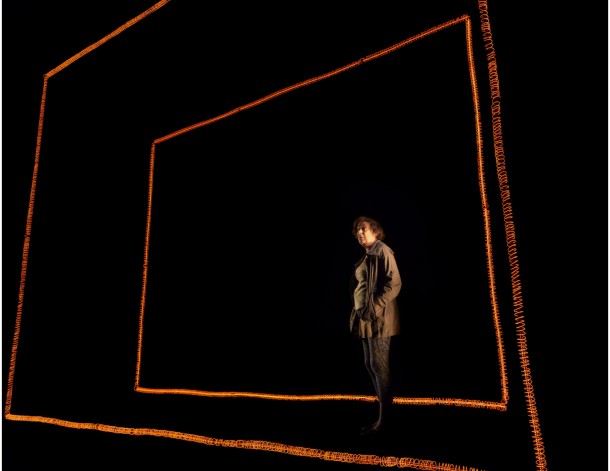

The production opens on a fenced-in yard set against a clear blue sky, with bits of green grass visible between the slats. Mrs. Jarrett, played by the wonderful Linda Bassett (reminiscently recognizable from images of the original production of Churchill’s Top Girls), tells the audience: “I’m walking down the street and there’s a door in the fence open and inside are three women I’ve seen before.” The women know she is there, invite her in, and the downstage fence disappears. Throughout the rest of the play, in present action, the four women sit and chat together on the lawn. The “regulars” are Sally (whose backyard they occupy), Lena, and Vi, beautifully played respectively by Deborah Findlay, Kika Markham, and June Watson. These three clearly have close and deep connections: they implicitly and explicitly express knowledge about one another’s secrets, phobias, families, and histories, some of which are shared, gradually, with the newcomer, Mrs. Jarrett. The “action” (or, more accurately, conversation) unfolds over eight scenes, which take place in the summer over “a number of afternoons”; these scenes are interspersed with soliloquies delivered by Mrs. Jarrett (from some future time?), during which the backyard magically vanishes, and is replaced by what appears to be a dark, empty space, framed with spirals of red light. (Think Beckett: we’re not sure where she is.)

Linda Bassett, Deborah Findlay, Kika Markham, and June Watson in Escaped Alone by Caryl Churchill. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

In the backyard scenes, the women speak in language that evidences Churchill’s never-ending inventiveness. As the playwright who created and popularized a “slash,” dash, and asterisk system for marking interrupted and overlapping dialogue, in her recent plays, Churchill writes in fragments. Many lines are without punctuation. In Escaped Alone, these fragments are used to create different effects: sometimes the characters appear to know one another well enough to finish each other’s sentences; sometimes they interrupt to correct one another, stop one another from saying the wrong thing, or to redirect the conversation; and at other times lines are spoken as if the characters’ thoughts float in the air, unfinished—until another speaker fills the empty space.

Mrs. Jarrett’s soliloquies occur “out of time”; it is not clear when then are happening, except that she uses the past tense to talk about innumerable, terrible tragedies that have already occurred. But Churchill is self-referentially witty: in the course of the “current” conversations (those occurring in Sally’s yard), the women refer to “parallel universes,” science fiction television, and even make a “knock-knock-joke” in which the punchline (if not too juvenile to say) would be “Dr. Who.” Mrs. Jarrett’s tales are awful—but also awfully funny. Churchill doesn’t only turn, but also twists her phrases, so that the horrific is also hilarious. In a tone of matter-of-fact (and even light-hearted) reportage, Mrs. Jarrett delivers headlines like these to the audience: “Miscarriages were frequent leading to an increase of opportunities in grief counseling” and “Governments cleansed infected areas and made deals with allies to bomb each others’ capitals.” Much of her reporting doesn’t make much sense; if one were to read the lines (as printed in the program), one might not perceive the humor that the production delivered. The apocalyptic images bear resemblance to those Churchill used in Far Away (2000), but here, the chilling effect is warmed with wit—and with an almost-cheery delivery.

Meanwhile (or intermittently), in the backyard, the apparent subjects of conversation are banal: lost keys, relatives, shopping, television, haircuts, hip replacements, mathematics, and memories. But isn’t this the stuff of life itself? As the afternoon scenes progress, secrets are revealed, sometimes to and among the assembled group of four, and at other times only to the audience, with each character having her own “private” moment of direct address. Lena and Vi know that Sally has a fear of felines, but the depths of her phobia are revealed in an aria of mounting distress that culminates with her saying, “I need someone to say there’s no cats…I have to believe they know there are no cats…And then briefly the joy of that.” Sally’s fear can only be appeased if someone she trusts tells her there are no cats—there’s comfort found in company. (Findlay was both frightening and funny.)

Lena is deeply depressed, as her neighbors know, and as she confides to the audience: “Why can’t I just?” She immediately answers her own incomplete question: “I just can’t.” She says: “I sat on the bed this morning and didn’t stand up till lunchtime….It’s not so bad in the afternoon, I got myself here. I don’t like it here. I’ve no interest. Why talk about that? Why move your mouth and do talking? Why see anyone? Why know about anyone?” Her ruminations grow darker and darker, but when the scene shifts from the non-realistic direct address back to the group of four, Sally observes: “Your medication doesn’t seem very” and Vi adds “do you take it”—and the audience has a good laugh.

Vi, it turns out, has killed her husband, and spent six years in prison. In one afternoon session, the conversation turns, quite naturally, to cooking and kitchens. Then Churchill injects her dark humor, once again, when Vi tells the audience: “if you’ve killed someone in a kitchen you’re not going to love that kitchen.” (It may or may not read like it’s funny—but it was.) Vi recounts how difficult it was to explain to her son what her husband had been like and why she’d killed him. Yet when she relives the horror, she says about her child: “at least he phones, that’s the worst thing even worse than the blood and the thrashing about and what went wrong that’s a horror but the horror goes on not seeing him.” She says can’t breathe in the night, but she still gets up each morning and puts the kettle on—even though “the kitchen [the horror?] it’s always there.”

Escaped Alone is all about juxtaposition, in its structure, language, and tone. Near the end of the play, the utterly depressed Lena utters the phrase: “always wanted to go to Japan.” Sally quickly retorts, “get to Tesco [the grocery] first.” Vi jumps in, telling Sally, “that’s nasty,” and an argument ensues. (It’s not very nice to point out Lena’s depression and near-agoraphobia.) Then, in the printed script, Lena replies, “I thought it was funny.” Herein lies one of the great joys of the theatre: Kika Markham, as Lena, was laughing. The actress—and character—seemed to be be genuinely amused, throughout. The sardonic ribbing of her friends and neighbors, unexpectedly, even if momentarily, lifted the darkness.

Indeed, unlike Far Away (now fifteen years ago), Escaped Alone seems not only to tell and foretell tales of darkness, but also to lighten things—to lift our mood. And for this spectator (and reader), the play constantly called for community. Comparing the script, once again, to this premiere production of it, Churchill writes a scene labeled only with the number “6”, and the stage directions read: “All sing. SALLY, VI and LENA in harmony. MRS. JARRETT joins in the melody. They are singing for themselves in the garden, not performing to the audience.” Though Churchill did not make a pre-production song selection, the company chose “Da Doo Ron Ron,” which had been recorded in 1963 by a “girl group,” the Crystals. As the women sang in perfect harmony, a suggestion of sisterhood emerged; their music-making brought momentary relief—and perhaps even a spark of joy? It seemed as if it did for them—and it certainly did for us.

And yet…When Mrs. Jarrett finally has her own moment of direct address from within the garden walls, she speaks only two words, which she says twenty-five times. “Terrible rage.” The outwardly amiable visitor is boiling over…. And yet…

Mrs. Jarrett began the play with the story of her arrival at the garden doorway, and she concludes the play narrating her departure from it. After the group has shared a final moment of apparent agreement, and even contentment: “it’s nice” … “always nice to be here” … “I like it here” … “Afternoons like this”—, Mrs. Jarrett turned to the audience and spoke these words: “And then I said thanks for the tea and I went home.” The lights went out onstage. And Churchill wrote: End.

***

Reviewer’s “aside”: I happened to see Escaped Alone on the final night of its inaugural production at the Royal Court Theatre, on 12 March 2016. Before entering the auditorium, I encountered the playwright at the doorway to the women’s room (fittingly enough). For those of us who have taught, written about, directed, or acted in her plays (and I count myself in each of those categories), Caryl Churchill is something of a feminist theatre icon. I did not approach her (too polite for that), but during the performance, from my lofty seat in the first row of the circle, I did sneak a few peeks at her in the stalls below. For this fan, Escaped Alone seemed—dare I say?—almost optimistic. Throughout the text—even in the midst of upsetting images—the action, language, and characters seemed to me to continue to return to community. And I saw Caryl Churchill, laughing at/with the actresses in the company—at her creation—and afterwards, as she warmly and laughingly embraced her own community at the cast party, downstairs, at the Royal Court bar and restaurant. As a member of the “theatrical community” writ large—and as a feminist scholar—I found the play, its production, and the entire evening to be heartening. And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.

is the author of An Actress Prepares: Women and “the Method” (Routledge 2012). Her research focuses on American theatre, feminist performance, acting theory and practice—and the intersections among and between these subjects. Her work has recently been published in the Routledge Companion to Stanislavsky, Shakespeare Bulletin, Theatre Annual, and the Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism. She holds a doctorate in Theatre from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and is a senior lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, where she frequently directs student productions.

European Stages, vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring 2016)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elyse Singer, Managing Editor

Clio Unger, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Hamlet in a Curious Nutshell by Maria Helena Serôdio

- Alvis Hermanis Productions in Latvia and German-Speaking Countries by Edīte Tisheizere

- The Unknown, the Unexpected, and the Uncanny: A New Lorca, Three New Catalan Productions, and a Few Extras by Maria M. Delgado

- 2015 Dance Week Festival and Contemporary Croatian Dance by Mirna Zagar

- Archives, Classics, and Auras: The 2016 Oslo International Festival by Andrew Friedman

- The Stakes for City Theatres: Linus Tunström’s Farewell to the Uppsala Stadsteater by Bryce Lease

- Life is Beautiful? or Optimistically About Bulgarian Theatre? by Kalina Stefanova

- The Multiple Dimensions of the Bulgarian ACT Independent Theatre Festival 2015 by Angelina Georieva

- Theatre in Berlin, Winter 2015 by Steve Earnest

- Musical Theatre in Berlin, Winter 2015 by Steve Earnest

- Gob Squad’s My Square Lady at the Komische Oper by Clio Unger

- New Productions in Berlin by Yvonne Shafer

- Manifest for Dialogue: Antisocial by Ion M. Tomuș

- A Fall in France by Heather Jeanne Denyer

- The Iliad as an Oratory: A Warning to a Civilization by Ivan Medenica

- Escaped Alone by Caryl Churchill at the Royal Court Theatre by Rosemary Malague

- Bakkhai at the Almeida Theatre reviewed by Neil Forsyth

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016