During a brief visit to Madrid in April 2015, I saw four plays. They ranged from a spectacular production at the Teatro Español’s Matadero of Fernando Arrabal’s latest work, Pingüinas, to a surprisingly moving one-woman reading of Itziar Pascual’s Variaciones sobre Rosa Parks, performed by the author herself, at José Sanchis Sinisterra’s Nuevo Teatro Fronterizo. Placed on my spectrum from exceptionally expensive to truly minimalist were Íñigo Ramírez de Haro’s Trágala, trágala on the main stage of the Teatro Español and Fernando J. López’s two- hander De mutuo desacuerdo at the commercial Teatro Bellas Artes.

Arrabal’s Pingüinas

Juan Carlos Pérez de la Fuente was named to a four-year term at the helm of Madrid’s municipal Teatro Español, starting 11 July 2014, but the previous director Natalio Grueso, who took over in 2012, had already made arrangements for the 2014–15 program. He had not, however, accounted for the Teatro Español’s Naves at the Matadero (former slaughterhouse). Pérez de la Fuente promptly named in Fernando Arrabal’s honor one of two halls converted there into theatres. The recognition was no doubt merited. Arrabal (b. 1932), who has lived in Paris most of his life, is the best known contemporary Spanish dramatist and author in the world.

Pérez de la Fuente reports that he contacted Arrabal in September, asking that he write a work to commemorate the 400th anniversary of part 2 of Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quijote. Four months later, the director had in hand the script that he declared to be Arrabal’s greatest work. The production at the Fernando Arrabal Theatre was so spectacular that the script at times faded into the background. The two native speakers of Spanish who attended with me on Sunday, 26 April said that, like me, they had trouble following the dialogue. The famous actor Nati Mistral, who attended on the triumphant, official opening night 29 April, was quoted in eldiario.es as saying she understood the text not at all—and she was seated in a front row. Nevertheless, some spectators caught jokes, producing sporadic laughter. The text includes references to various works by Cervantes and those lines were easier to catch than some others that, despite the use of microphones, were often shouted rather than spoken.

Given the stunning performance, perhaps the lost text didn’t matter. In his program notes, Arrabal affirms that these “Quijotas” or “Cervantas” make no commentaries and teach no lessons. They reflect the essence of Don Quijote, which proclaims liberty above and beyond sanity and madness.

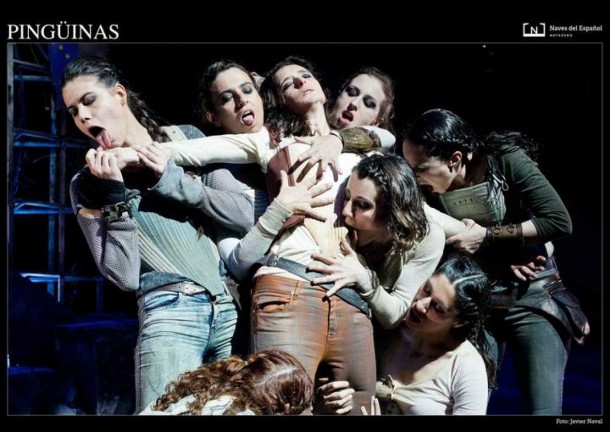

The female penguins of the title are ten women in the Cervantes family, ranging from his grandmother to his illegitimate daughter. Before the action begins, their names and relationship to Cervantes, along with their birth and death dates, are projected for the benefit of spectators seated on two sides of the stage area, facing a central structure that resembled a space launch tower. The cast consists of ten women and one man, who wears a shirt labeled “Miho” and is loudly proclaimed to be the son of them all.

The term “pingüinas” is inspired by an annual gathering of the Penguins motorcycle club. The casting call for the ten women specified that the actors had to be able to handle emotional, physical roles and to ride motorcycles. Despite the latter requirement, there were one thousand applicants. Perhaps the most famous in the final list of ten is Ana Torrent, who portrayed Luisa de Belén, Cervantes’s sister who was a nun. Others who play major roles are María Hervas as Torreblanca, the grandmother, and Marta Poveda as Constanza, the niece.

All ten roles are indeed physical, involving constant motion and costume changes. Among the costumes, designed by Almudena Rodríguez Huertas, quasi-military camouflage garb dominates; these are layered, facilitating rapid transformations. Near the end of the production, seven of the women appeared as brides, donning white skirts over hoops. In a final scene, located presumably in a mental health facility, they wore orange costumes.

Marta Carrasco created an outstanding movement and choreography design. The playing space, with tiered seating on two sides, featured a wide entrance in the middle of one of them and was open on the other two sides except for supporting posts. Most surprising, she choreographed motorcycle action as the bikes circled around the stage area in various formations. The bikes appeared perilously close to one another but there were no collisions. Front ends of bikes were at times topped with heads of horses or horned animals. The motorcycles alternated between entering the stage soundlessly and roaring in.

Equally impressive was the lighting, created by José Manuel Guerra that culminated in a fireworks display rising up the tower. The Cervantes character made several aerial entrances from the side. To represent the Spanish author’s extended imprisonment in Africa, where he was held for ransom, Miho flies in a cage.

Arrabal is celebrated for his provocative, transgressive theatre. Pérez de la Fuente may well be right that the chaotic action of Pingüinas could prove to be the Spanish author’s greatest work. Certainly the spectacular staging at the Matadero will not soon be surpassed.

Grueso’s Trágala, trágala

Among Natalio Grueso’s last projects at the Teatro Español was Trágala, trágala, Ramírez de Haro’s satire of Spain’s nineteenth-century despotic King Fernando VII, directed by Juan Ramos Toro. The title recalls a grotesque song that was used during a series of civil conflicts to advise the losing side of the moment to swallow their defeat. Neither the title nor the action of the play, thoroughly immersed in Spanish history and current affairs, is likely to transcend Spain’s borders. Numerous quotations from Fernando VII were projected prior to the beginning of the stage action; some of his outrageous comments could readily be applied to political attitudes toward social problems today. The various episodes related to the royal family of two hundred years ago are well known within the country and were flamboyantly presented by Yllana comedy troupe. In case spectators had forgotten details, the production provides a rapid, madcap refresher course on the historical background.

Nevertheless, some Spaniards were left unimpressed by the spectacle and what they considered inappropriate references to the current royal family, but the full house when I attended on Saturday, 18 April, received the performance with much laughter and applause. Spectators clearly enjoyed the production even though it ran almost two hours without intermission.

Although one can find superficial parallels between past and present royal families, notably in the ascension to the throne of the son upon the father’s abdication, Fernando VII is known as the worst king in Spanish history and King Felipe VI, who has far less power, is currently admired by his people.

One critic wondered why Grueso chose to stage this particular playwright when so many talented young dramatists await their debuts at the Teatro Español. I have no ready answer to that question. The director Íñigo Ramírez de Haro, Marqués de Cazaza (b. 1954) served in the Spanish diplomatic corps for some three decades. He has been director of cultural programs at Madrid’s Casa de América and for several years was the cultural attaché at the Spanish Consulate in New York City. His theatre tends to be deliberately irreverent and at times scatalogical, quite inconsistent with his elitist educational background.

The Spanish friend who attended the performance with me thought Trágala, trágala was dated: that it might have been more effective in the 1980s. Interest in specific political satire tends to fade over time. In 1975, the year when Francisco Franco died, Manuel Martínez Mediero’s Las hermanas de Búfalo Bill was a hit. The revival I saw a quarter-century later played to an almost empty house at the Teatro Muñoz Seca; spectators I spoke to had no idea that “Buffalo Bill” was a spoof on the deceased dictator who was known for laws repressing sexuality. The Fernando VII piece is less arcane for today’s audiences. In some ways it reminded me of Transición, a work that proposed to introduce contemporary audiences to the Adolfo Suárez period that followed Franco’s death [See ES 1.1 (Fall 2013)].

The parallel occurred to me at the conclusion of Trágala, trágala when the king is taken offstage in a wheelchair by healthcare workers. At that point a possible interpretation emerged that the supposed king, who entered the stage through a trapdoor, did not come from his tomb to relive his past and become acquainted with the present but rather was a man suffering from an elaborate delusion like the Suárez figure in Transición. Such a psychological explanation clarified the repeated, comic appearance of an Argentinian psychoanalyst who, with Freudian terminology, tried to resolve the deceased king’s attachment to his mother and conflict with his father. It is no doubt mere coincidence that Pingüinas also ends in a mental home.

Another aspect in common between Trágala, trágala and Transición was the introduction of a TV commentator, a major component of the play about Suárez. In the Ramírez de Haro production, Ana Cerdeiriña’s sporadic appearances in this one of her three roles were intended to imitate the current queen, Doña Letizia, who had been a journalist and TV news anchor. Perhaps none of these thoughts is of any real significance. In his program notes, the playwright affirms that he wrote the text simply to elicit some laughter and we should think no further.

The seven men and two women in the Yllana troupe gave spectators ample reason to laugh. The non-stop action and rapid dialogue are marked by comic techniques, among them use of foreign accents (Argentinian and French), sexual references (an enormous phallus as part of Fernando VII’s costume), and incongruities (arising from anachronisms). The Brechtian staging made use of the center aisle, with house lights up, and improvised interaction with the audience. Also Brechtian was the incorporation of narrative comments, provided by the TV personality, to provide identifying labels for the rapid history lessons.

The use of doubling, including cross-gender casting, added to the humorous impact. Worthy of attention in this respect was the performance of Balbino Lacosta as Queen María Luisa—along with his portrayal at other moments of three male roles. Fernando Albizu brought Fernando VII to life with great flair both in his physical resemblance to the nineteenth-century king and his outstanding caricature of the historical figure.

The lively production was enhanced by musical numbers, including a small onstage band, and colorful costumes. The nineteenth-century dresses, designed by Tatiana de Sarabia, provided discreet cover for sexual encounters during the rollicking tales of King Carlos IV’s impotence, the queen’s liaison with Manuel Godoy, and Fernando VII’s attempts at seduction with his enormous, and hence comic, male organ. Exaggeration provoked laughter. Carlos IV’s successful begetting of Fernando VII is proclaimed a “miracle,” one that is helped along by prior stimulus of María Luisa by Godoy.

The family of Carlos IV is internationally known because of Francisco Goya’s famous painting of that name. An effective highlight of Trágala, trágala was its ekphrastic element, in which that painting was partially visualized. Among Joshean Mauleón’s four roles was that of Goya, located downstage, by his easel—precisely like the artist’s self-portrait in the royal family portrait—while actors behind him were readily recognized as figures in the painting.

López’ De mutuo desacuerdo

Born in Barcelona in 1977, Fernando J. López soon moved to Madrid and received a university degree in Hispanic Philology from the Complutense. In addition to being a playwright and director, he has written novels and teaches at the secondary school level. De mutuo desacuerdo (By Mutual Disagreement) opened almost simultaneously in Spain and in Venezuela. At Bellas Artes, it was scheduled from 1 April to 31 May. When I attended on Sunday, 19 April, the 455-seat theatre was filled and the audience, enthusiastic. Directed by Quino Falero, the production featured Toni Acosta, who is primarily known for her work in television, and Iñaki Miramón, a well-known actor of film, stage, and TV. They portray a recently-divorced couple who are forced to deal with the behavioral problems of their young son, Sergio. The episodic action stretches over a period of weeks, leading up to a year following the divorce.

Passage of time and spatial fluidity are marked by effective costume changes and by a movable set with a number of convertible features. When upstage, the set indicates Sandra’s apartment and when shifted downstage it becomes Ignacio’s. It also provides a table and chairs to establish a restaurant. I did not find the ultra modern set particularly attractive but its versatility is admirable. Both costumes and set were designed by Mónica Boromello.

In its fast-moving comic action and rapid dialogue, De mutuo desacuerdo hits a familiar range of problems that led to the breakup of a marriage after fourteen years. Primary among these is that Ignacio is a workaholic who paid scant attention to his wife; as a result, Sandra had an extra-marital affair that precipitated the divorce. Now, Ignacio wants as little contact as possible with their son. Moreover, his only friends are at the ad agency where they both work. His new girlfriend makes Sandra’s life miserable and then arranges for her to be fired. Sandra’s personal and professional lives collapse, but Ignacio’s situation is no better.

References to past marital problems are revealed in conversations between the former spouses while current issues are shown, rather than told. Both are drinking more and enjoying life less. Sandra, whose brief relationship post-divorce is no more, dresses up for her birthday to fake an imaginary date when Ignacio stops by her apartment. By the end of the play, Sandra has come to terms with her new role, has found a new job, and is back to composing music. Ignacio has agreed to share custody of their boy, who has been in trouble at school, so that he can help in the child’s adjustment.

As is typical of two-handers, there are references to offstage characters and phone calls. Sandra speaks several times to her sister, whom Ignacio dislikes. Most significantly, Sergio is represented by a bedroom door. We are to understand that he hears his parents argue. When Ignacio says the boy will go with his father, the door starts to open; when Sandra says he isn’t leaving her home, the door closes. In a scene with this repeated comic action, the audience laughs heartily even while realizing how much the child is suffering.

In his author’s note in the program, López suggests that the invisible Sergio, who shuttles between two homes with his backpack, is representative of divided families in the twenty-first century. He affirms that the child of a broken home like this is barely seen in Spanish theatre and literature. It is not difficult to refute his statement about the present treatment of the subject and to discover that the negative impact of divorce on children is not a new phenomenon. In his plea for divorce reform in the late 1970s playwright Jaime Salom focused on the plight of the daughter in La piel del limón (Bitter Lemon, trans. Patricia O’Connor); twenty years earlier, in the mid-1950s when the previous divorce law during the Republican years had been annulled retroactively and even the word divorce was taboo in Spain, novelist Elena Quiroga highlighted the situation of the daughter of parents who separated in the 1930s in Algo pasa en la calle.

In Madrid, there is a proliferation of new little theatres as well as established playhouses that rotate several plays a week or more than one play an evening. This micro-theatre effect results from the increasing number of actors, many of them trained at the Royal School of Dramatic Arts, who need to work professionally, along with the negative impact on culture of a twenty-one percent value-added tax that has been imposed on stage productions. José Luis Alonso de Santos, president of Spain’s new Academy of Performing Arts, calls these spaces “family theatres”: If a production involves at least seven people, each of whom has ten relatives who can be counted on to buy a ticket and attend, a play can reach several performances in a little theatre. He points out that there are no “comps” to such productions; everyone pays the entrance fee, including the author.

Pascual’s Variaciones sobre Rosa Parks

By extension, plays are being performed in unexpected places. A friend tells me she went to a production in a beauty salon. At entrance spectators purchased a hair curler (not a ticket) and sat in salon chairs. In this unique setting, the high tax on culture was artfully avoided and the audience was enthralled by the piece.

José Sanchis Sinisterra’s Nuevo Teatro Fronterizo is not part of the micro-theatre movement per se although it is located in the Lavapiés area of the city where some of those spaces have appeared. Sanchis Sinisterra (b. Valencia, 1940) developed his famous Teatro Fronterizo in Barcelona but moved to Madrid some twenty-five years ago. Although he says by now he should be retired, he is in fact running a theatre laboratory, research institute, and drama and film school in a former corset shop. Among the various spaces in the building is one dedicated to the “author’s voice,” where playwrights may present a recent work or work in progress to spectators who are seated on folding chairs. There is a little stage for the presenter, an amplification system, and connections for a computer. On the evening of Wednesday, 22 April, Itziar Pascual gave a one-woman staged reading of her 2008 Rosa Parks play.

I was already familiar with the text of Variaciones sobre Rosa Parks; at Itziar Pascual’s request, I wrote the prologue for the published edition. Nevertheless, I was amazed at how brilliantly Pascual presented her play to an audience of some twenty people in the little auditorium. Most of them had not seen the play staged and had not read it but were able to follow the action with ease despite the fluidity of space and time. The elderly Rosa Parks remembers episodes from her life dating back to 1955. She carries on a dialogue with the Shadow of Rosa Parks. The author distinguished between the voices of the two characters, controlled background music and other effects of a sound track. Far more than a mere reading aloud of her text, it was a performance that suggested how readily her script, with proper direction, could be performed as a radio play or audio book. The spectators had high praise for her performance and remained for an animated discussion.

Variaciones sobre Rosa Parks also reminds us that there are many variations of theatre, and that audiences may be captivated by a range of productions from spectacular stagings created at considerable expense to polished readings with minimal requirements.

Phyllis Zatlin, professor emerita of Spanish and Translation at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, has written extensively on contemporary theatre and has translated over twenty plays from Spanish and French that have been performed and/or published. Most recent production has been Policy, by Antonio Munoz de Mesa, staged by Rogue Theater in Sturgeon Bay, WI; her most recent book, published by ESTRENO Studies, is Writers to Remember: Memoirs of Friendships in Spain and France. She is a member of The Dramatists Guild.

European Stages, vol. 5, no. 1 (Fall 2015)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Elyse Singer, Managing Editor

Clio Unger, Editorial Assistant

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- Avignon the 69th Festival, July 4 to 25, 2015: Discovery Beyond The Classics by Philippa Wehle

- The 2015 Oslo International Festival at Black Box Theatre by Andrew Friedman

- The 2015 Theatertreffen by Marvin Carlson

- A Feminist Tuberculosis Melodrama: Melek by Theatre Painted Bird by Emre Erdem

- Nachtasyl at the Berliner Schaubühne: A Radical View of Gorky’s The Lower Depths by Beate Hein Bennett

- From Spectacular to Minimalist: Four Plays in Madrid, April 2015 by Phyllis Zatlin

- European productions at Montreal’s Transamériques Festival 2015 by Philippa Wehle

- Childish or Adult? Recent productions in Germany by Roy Kift

- Russian Drama in Finland by Pirkko Koski

- Troubling Cross-Currents in the Budapest National Theatre by Marvin Carlson

- Spain: Engaging with la Crisis Through Theatre by Maria Delgado

- Life and Death in the Emergency Room: Linus Tunström’s Faust 1 at the Staatsschauspiel Dresden by Bryce Lease

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

©2015 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016